Introduction

From the Court’s Beginnings Until 1968

The Transformation in Judicial Education Begins: Progress During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s

The Transformation Takes Root: From 1990 Onward

Conclusion

Appendix A

Appendix B

Introduction

As the Ontario Court of Justice evolved, passing through its many incarnations, formal education[1] went from something dismissed as unnecessary and inappropriate to become an essential element of the continuing professional development of judges and justices of the peace. Informal education – studying and reading on one’s own or learning informally from one another – had always been an aspect of judging and actively encouraged. But structured, organized continuing education did not begin in earnest until the 1960s.

How did this happen and why?

From the Court’s Beginnings Until 1968

The Magistrate’s Approach to Education: “Why, this job is actually very simple!”[2]

Common sense and intuitive feelings developed through past experiences ruled the day for many magistrates and justices of the peace – and defined their approach to decision making. The culture of the Magistrates’ Court, the backgrounds of those who sat as judicial officers, and the approach to judging reinforced the opinion that formal judicial education was not only unnecessary, but actually an affront.

“I depend upon an intuitive feeling as to a man’s guilt or innocence and not to weighing and balancing the evidence…” wrote police magistrate, Colonel George Taylor Denison in 1920.[3] He was close to retirement at this point, after serving in Toronto’s Magistrates’ Court since 1877. His disrespect for the rule of law was palpable. “My main desire has been above all things to administer substantial justice in all cases coming before me. This I felt should be done in preference to following legal technicalities and rules…I never follow precedents unless they agree with my views.”[4] The “law unto Denison” prevailed in his court – an individualistic approach that many magistrates and justices of the peace adopted. To their minds, education was simply not necessary.

Although Denison was a lawyer and cavalry officer prior to becoming a magistrate, the vast majority of judicial officers of that day had no previous legal training and did not see this as an impediment to fulfilling the role of magistrate. David Vanek, who later became a magistrate and then a judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division), recalled – with shock – an appearance in Magistrates’ Court he made when practising law in the 1960s. Vanek’s experience during that appearance vividly evokes the impact of a lack of training either before or after appointment to the bench.

“I recall making a strategic error in Magistrates’ Court when, in addressing the Bench, I argued that the case should be dismissed because the prosecution had failed to disclose any evidence of mens rea, probably the most basic concept of criminal law. It refers to a guilty mind or some quality of intention that is an essential ingredient of every criminal offence. It was obvious that the magistrate did not know what I was talking about.”[5]

A Manual for Magistrates: Published in 1962

By the 1960s, as more and more lawyers were being appointed to the Magistrates’ Court, the resistance to formal education assumed a slightly different tone. In general, the opposition took two forms:

• a perception that it was unnecessary because of the expertise lawyers brought to the bench; and

• a concern that education would interfere with the impartiality and independence integral to the work of a magistrate.

This opposition is evident in a manual written in 1962 by S. Tupper Bigelow, a lawyer and magistrate, to serve as a guide for all magistrates, but particularly tailored for new appointments to the bench.[6] Great care is taken in the introduction to Bigelow’s book – even though it is intended only as a guide – to reassure readers that judicial independence is of primary concern: “Each magistrate, of course, must in each case make up his own mind not only as to sentence, but also as to questions of law.”

Bigelow acknowledged that some judges, at the time, did receive formal training, but dismissed that approach as inappropriate for Ontario magistrates.

“In some European countries, there are schools for judges, and perhaps such a system has its merits. However, in all English-speaking countries, a judge or magistrate commences his duties on appointment without any instruction whatever. He probably thinks of the best judge or magistrate he has ever seen in court, and does his best to emulate him in performing his own duties.”[7]

In Bigelow’s world, education was to be undertaken only on an “as needed,” individual basis – and it was very much directed at the new appointee who wanted to learn court procedures, as opposed to the law. Knowledge of the law was assumed – and the experienced magistrates – “the seasoned fellows,” as Bigelow referred to them – were assumed to already have all the education they needed.[8]

“It would be well for the newly appointed judge to sit in court with a fellow magistrate until he thinks he has the ‘feel’ of the job….After court, he will naturally ask many questions, which the senior magistrate will only be too glad to answer. If possible, he should sit in this way with as many magistrates as he can. Thus, he will find many viewpoints on the same questions, and he will be able to reconcile them as best he can for his own purposes….There will come a time, and it will not be long, when the newly appointed magistrate will think, ‘Why, this job is actually very simple!’”[9]

This informal system continued – unabated until the late 1960s – as the only education a new judge would receive.[10] And that system often proved to be pretty thin gruel for many a new magistrate. Bill Sharpe, appointed in 1971, recalled his education this way:

“My training was watching Judge [Robert] Dnieper for a morning, after which he said I looked good to go and left to play golf. I also spent a few days with Judge David Vanek too. I think they felt that since I had been practising law for at least 15 years, I knew what I was doing.”[11]

Justice Sidney Lederman, an Ontario Superior Court judge, was – during his tenure as an evidence professor at Osgoode Hall Law School – an early advocate for judicial education programming for federally appointed judges. Here is how he characterized the early resistance of judges to education from anyone other than a fellow jurist. “They didn’t want to hear from an academic. They thought it was a Marxist idea to have someone from the outside become involved in judicial education. They thought it could be a vehicle to influence the court by special interests. The other theory was that ‘we know the law, what can they tell us?’”[12]

Changes Began with the Organization of an Association of Magistrates

In the early 1960s, magistrates formed an association and began holding annual conferences. While these conferences were primarily social events, they were also multi-purpose, since they provided the only opportunity for magistrates from across the province to get together and discuss matters of common interest. Discussion was “devoted to securing an increase of remuneration and pensions, which were at unreasonably low levels, and improving working conditions,” recalled Vanek.[13] As well, educational programming was tacked on to the conferences, which provided justification for funding by the provincial government. The Court had no power over its own funding – and relied on the good graces of the government of the day to pay for these gatherings.[14]

David Vanek recalled that the educational component tended to be thin in content.[15] And, given the funding structure, the magistrates could also expect a presentation from the “funder” – the Attorney General of the day – who would have no hesitation in “putting them in their places,” and demonstrating that judicial independence was a flimsy construct.

“Talkative Magistrates Are Laid Low by Attorney-General Fred M. Cass”

At the 1962 annual conference organized by the Ontario Magistrates Association, the group received a lecture from Fred Cass, the Attorney General, on his view as to how a magistrate should manage the courtroom. The Kingston Whig-Standard reported Cass delivered a “blistering attack” on the magistrates. When a magistrate interrupted Cass with a question betraying disagreement with his suggestions, the newspaper reported: “The attorney-general turned both barrels on the interrupter, saying ‘It is my impression that our courts are there to serve the public. If I find that this is not the view of anyone occupying any court over which I have jurisdiction, that person will be forthwith removed.’”

A Similar Situation Prevailed in Juvenile and Family Courts

The experience of judges in Juvenile and Family Courts was quite similar to that of the magistrates. “Judges did not receive any training for presiding over these specialized courts,”[16] wrote Ted Andrews, who served as Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) from 1968 to 1990. A noticeable effect was evident in the quality of the work of these judges. As Andrews pointed out, “they conducted their Courts in their own peculiar way, and were given pretty much a free rein.”[17] This resulted in “a lack of uniformity in practice.”[18]

Recognizing this shortcoming, the judges took it upon themselves to form the Association of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. Andrews reported that the association “undertook a critical study of the various facets of the operation of the Juvenile and Family Courts…As a result, the Association made numerous recommendations for improvement to the Attorney General who was responsible for the administration of the Courts. With the co-operation and financial support of the senior people in the Attorney General’s Department, the Association began holding its own annual seminars in an attempt at self-education of its members.”[19]

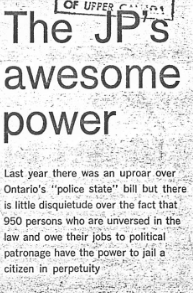

Justices of the Peace – The Sorriest State of All

Fifty years ago, justices of the peace faced an even more daunting challenge of learning the job than magistrates and Juvenile and Family Court judges. A 1966 Globe Magazine article, “The JP’s awesome power,” detailed the broad scope of the jurisdiction of the justices of the peace, the fact there was no requirement for them to be legally trained, and then pointed out: “JPs get no formal introduction in their duties. By the provincial Justices of the Peace Act, each JP who is appointed must be examined and certified by a County Court judge before he takes up his duties. In practice, the questioning usually takes a perfunctory five or 10 minutes. After that, though the JP is presumed to call on the nearest magistrate or Crown Attorney if he needs guidance, he is on his own.”[20] A new justice of the peace was lucky to be given his or her own copy of the Criminal Code.[21]

The Transformation in Judicial Education Begins: Progress During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s

The advance toward instituting formal judicial education began in the 1960s for judges and picked up steam in the early 1970s, following the demise of the Juvenile and Family Courts and the Magistrates’ Courts and upon the creation of the Provincial Courts (Criminal and Family Divisions). This trend continued throughout the 1980s and by decade’s end, it was generally accepted that judges needed access to continuing, high-quality education throughout their careers. Serious challenges remained, however, in providing that education to all judges, and justices of the peace didn’t see the same degree of progress until well into the 1990s.

What Led To Education and Training for Judges Becoming a Priority?

In the case of Ontario’s Provincial Courts, three important developments contributed to judicial education becoming a priority:

1. A more visible Court and judiciary.

2. Strong judicial leadership.

3. Societal and judicial recognition, and acceptance, of the necessity of adult education.

A More Visible Court and Judiciary

In the 1960s and 1970s, the academic, legal and media worlds began to research and write about the Provincial Courts – both family and criminal – identifying the importance of the work and the difficulties the judiciary and the courts were experiencing. These voices were often critical, recommending judges and justices of the peace needed formal education to develop a “greater level of sophistication” in their approach to their work.[22]

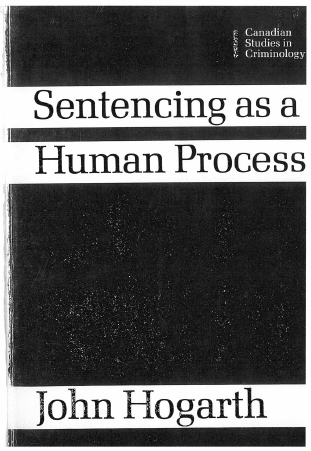

Sentencing as a Human Process: Professor John Hogarth

Perhaps the most important and influential research was authored by Professor John Hogarth, then the Director of the Institute of Public Policy Analysis at Simon Fraser University. He was insistent that judges needed education – “an urgent need,” he concluded.[23]

His ground-breaking book, “Sentencing as a Human Process,” was published in 1971 through the new Centre of Criminology, University of Toronto, the result of intensive, structured interviews with 71 full-time Ontario magistrates (virtually everyone in the province), together with extensive analysis of their various cases, decisions and sentences imposed.[24]

Hogarth acknowledged, at the outset, that “Magistrates’ Courts have been under considerable and mounting criticism.”[25] He concluded that “50% of the variations in sentencing could be accounted for simply by knowing certain pieces of information about the judge himself” and that “…the judicial process is not as uniform and impartial as many people would hope it to be. Indeed, it would appear that justice is a very personal thing.” He also identified the direct and indirect ways that magistrates’ independence was being compromised, while providing strong evidence in support of all members of the Court being legally trained before appointment.[26]

Hogarth reported that the magistrates were generally gratified by their participation in this very important, original research. They felt isolated and overlooked, despite having heavy responsibilities within the justice system, deciding the vast majority of criminal cases in Ontario, and were delighted that someone – finally – was paying attention to the challenges they faced.[27]

In his concluding chapter, Hogarth made a forceful argument for judicial education. “The data presented here show that most magistrates sentence without a great deal of background information concerning the cause of crime or the results of research concerning the efficacy of different types of correctional methods. Few do any significant reading in this field and only a minority have visited penal institutions. No effective mechanism exists at present for bringing new information to the attention of the Courts, and, unless this is corrected, judges….are likely to continue to sentence ‘in the dark.’ There appears to be an urgent need to provide initial and ongoing training for judges.”[28]

Hogarth also provided specific advice as to the form and content future education initiatives should embody, along with not-so-subtle criticism of the quality of training offered to the judges at that time.) Education “should not be considered a frill that can be dispensed with in times of economic stress or pressures of work…training should not be directed solely to providing information…but primarily to enhancing the perceptual skills, human sensitivity, and critical abilities of judges and magistrates in handing information and assessing the results of research concerning the effectiveness of different types of penal measures.”[29]

According to Hogarth, the time was right for his book. “Although some judges were dismayed by what the book revealed, they felt proud – by opening themselves up, they were pioneers.” The book served as an important trigger for the introduction of a more formal and considered approach to judicial education. Hogarth explained: “That’s the way historical changes happen. Society was changing and the Court too was ready for change.”[30]

The academic world began to assume a key role in advocacy for judicial education during this period. Perhaps the most influential academics in bringing the issue to the fore were Professor John Edwards, who founded the Centre for Criminology at the University of Toronto in 1963, and Professor Tony Doob, whom Edwards brought to the Centre in 1971.

Both John Hogarth and Tony Doob noted that Chief Judge Fred Hayes (who was a Senior Judge when the research was conducted) was unhappy about the criticism levelled at his judges and the quality of the education provided to them. As a result, Hayes became less favourably disposed toward the research being done by the Centre of Criminology after the publication of Hogarth’s book. But there was support within the judiciary. Hogarth recalled he had judicial champions within the Provincial Courts who played important roles in building support for both the research and the book – and the education initiatives he proposed.[31]

Additional Recommendations for Judicial Education

Another influential book in the history of judicial education was Professor Martin Friedland’s 1965 analysis of the bail process, “Detention before Trial.” He, like Hogarth, examined magistrates’ decision making process. Friedland, a law professor at Osgoode Hall Law School, conducted a thorough study of pre-trial detention, and in his concluding chapter, he wrote: “…the magistrate deciding the bail must have sufficient knowledge on which to base an intelligent decision. The system in Toronto depends mainly on speculation, the view of likelihood of the accused appearing for trial merely from his looks in court.”(Source: Friedland, Martin, Detention before Trial: A Study of Criminal Cases Tried in the Toronto Magistrates’ Courts, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965))

Another influential book in the history of judicial education was Professor Martin Friedland’s 1965 analysis of the bail process, “Detention before Trial.” He, like Hogarth, examined magistrates’ decision making process. Friedland, a law professor at Osgoode Hall Law School, conducted a thorough study of pre-trial detention, and in his concluding chapter, he wrote: “…the magistrate deciding the bail must have sufficient knowledge on which to base an intelligent decision. The system in Toronto depends mainly on speculation, the view of likelihood of the accused appearing for trial merely from his looks in court.”(Source: Friedland, Martin, Detention before Trial: A Study of Criminal Cases Tried in the Toronto Magistrates’ Courts, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965))

The Work of the Court Becomes More Visible Through the Media

Both The Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star published numerous articles that put the Provincial Courts – and the judges sitting in them – in the public spotlight and subject to increased critical analysis.

In 1972, for example, Justice Edson Haines of the Ontario Supreme Court spoke out vociferously in Chitty’s Law Journal about the need for education for all judges in Canada – and called for the creation of a national institute for the education of the judiciary. The Globe and Mail duly reported on Justice Haines comments.

“Mr. Justice Haines wrote that most of those appointed to the bench have received their formal education a long time before. ‘They were average students. Their instruction varied, and they learned in haste concepts which they have not been able to develop. Lawyers practice the kind of law their clients bring them, with the result that they become adept in a few fields, fairly proficient in some, and as for the remainder they avoid them or consult another lawyer. A man can have a distinguished career in law and almost never appear in court. Now as a judge he must engage in the whole field of law. Many of the subjects were not even taught when he went to law school. No lawyer knows all the law, but we expect it of our judges….A judge needs the opportunity, time and assistance in the reduction of his ignorance. In many instances it will not be a case of re-tooling, it will be tooling up for the first time.’”[32]

The Criminal Law Reports (that included editorial commentary by its editor, Professor Alan Mewett, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto) and the Criminal Reports began including more Provincial Court decisions. Reporting these cases made the decisions of the provincially appointed judges visible (and, thus, open to scrutiny) in a manner never before manifest. Later, the Reports of Family Law were introduced, under the leadership of Judge David Steinberg, making the Family Court more transparent.

Voices Calling for Improved Judicial Education in the Family Court Arena

The Juvenile and Family Courts were essentially invisible in the 1960s, their work often done behind closed courtroom doors and subject to little academic and media analysis. Criticisms of the juvenile system became more public in the United States and Canada after the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court’s decision, In re Gault[33], that held juveniles accused of crimes in delinquency proceedings were entitled to due process protections, similar to those available to adults. Research in both Canada and the U.S. focused on the denial of children’s rights and on the perceived failure to protect their best interests, particularly in the child welfare system. Information about the significant number of aboriginal children in care, the impact of the “60s scoop,” and incidents of poor foster care started to emerge – highlighting the importance of the work being done by the judges in the provincial courts.

The “60s Scoop”

The 60s Scoop refers to the removal of large numbers of Aboriginal children from their families and their subsequent adoption by non-Aboriginal families in Canada between 1960 and the mid-1980s. This was done with little if any involvement of the families’ communities or bands.

(Murray Sinclair, Donna Phillips and Nicholas Bala, “Aboriginal Child Welfare in Canada” in Nicholas Bala, Joseph Hornick and Robin Vogl, eds., Canadian Child Welfare Law (Toronto: Thompson Educational Publishing, Inc., 1991))

Lawyers began appearing more frequently – and better equipped – in provincial Family Court proceedings beginning in the 1960s. At that time, academics such as Professor John Barber, at Osgoode Hall Law School, and Professor George Thomson, at Western University Law School, introduced areas of law being applied in Juvenile and Family Courts to the curriculum, such as child protection and proceedings under the Training Schools Act. Young lawyers entering the profession became more adept in crafting sophisticated arguments in Family Courts across the province. Similarly, the establishment of Ontario’s legal aid plan in 1967 and the steady growth in community legal clinics in the 70s, including law school clinic programs with a special connection to the work of the Provincial Courts, were powerful forces inevitably leading to a more transparent court.[34]

Judicial Leadership

Ontario’s Provincial Courts were acknowledged early pioneers in judicial education. This was a direct result of having two Chief Judges who served throughout the 1970s with a special interest in education, together with two judicial associations that began to take leadership roles in education.

Ted Andrews served as Chief Judge, Provincial Court (Family Division) from 1968 to 1990. Fred Hayes, his counterpart on the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) was Chief Judge from 1972 to 1990. Interestingly, Andrews appears to have had more success at providing education to the judges of the family bench.[35] “Although the family bench was small, Andrews was demanding of Attorneys General and got more for his judges’ educational programming than Hayes,” stated Allen Edgar, Research Counsel to the Court. “That continued when the two benches were combined (in 1990). Then it was a question of bringing the criminal bench up to the standard of the family bench in judicial education.”[36]

Leadership of Criminal Division Educational Programming

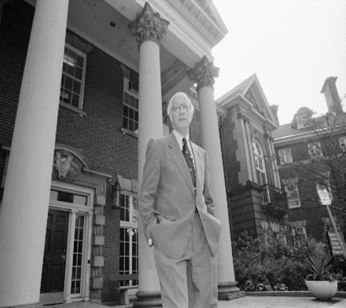

Annual conferences organized by the magistrates’ association date back to the 1960s. However, as indicated previously, these were primarily social occasions, combined with reports about the business of the Court, interspersed with lectures – usually delivered by magistrates – on the law.

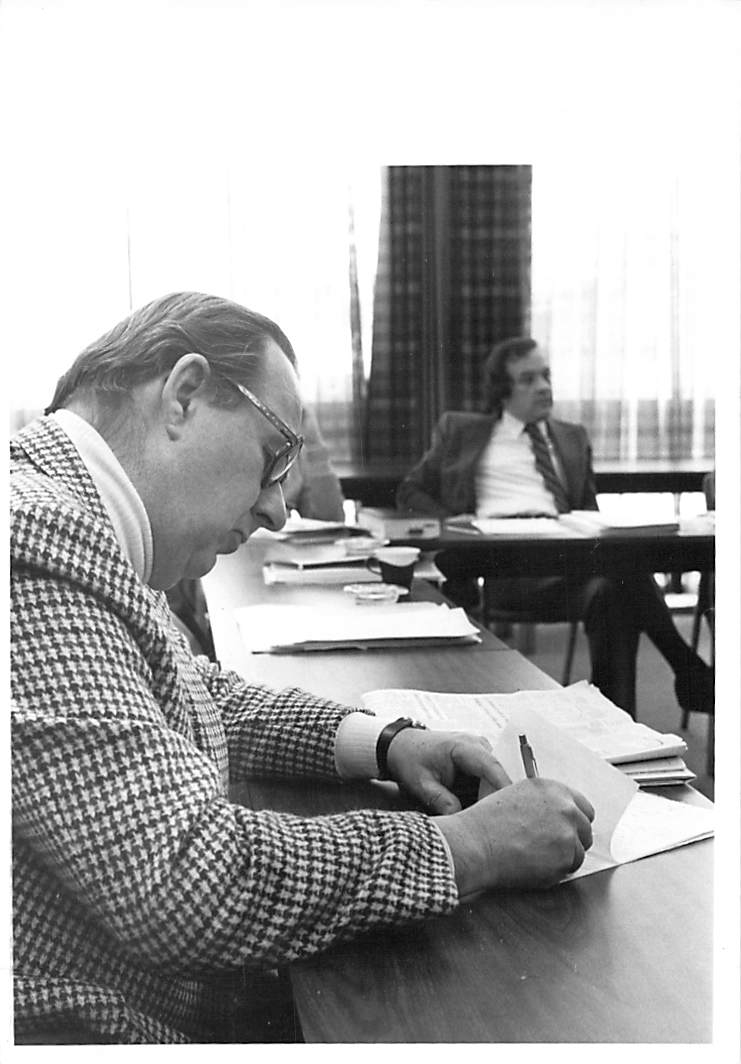

David Vanek, appointed to the Magistrates’ Court in 1968, wrote of his introduction to formal judicial education:

“Several years before I took office, the magistrates of Ontario had organized an association that held annual conferences and arranged educational seminars and meetings. After magistrates became judges (in 1968), the association continued to operate as the Provincial Judges Association of Ontario (Criminal Division)….I developed an interest in the educational programs of the association, although I found these to be lacking in substance.”[37]

Undaunted, Vanek stepped up to the plate and joined the Association’s educational committee, eventually serving for several years as chairman of the committee, aided by a group of equally devoted judges. Working with Chief Judge Fred Hayes, this committee kick-started a more comprehensive approach to judicial education, introducing new programming, including a week-long “University Judicial Education Program,” a collection of annual regional sentencing seminars conducted in four locales, and periodic visits to the Court of Appeal.

The judges were generally receptive to these new programs. As Vanek recalled, in the 1970s and 1980s, “successive governments have been responsible for the enactment of a huge amount of legislation that added enormously to the importance and burden of the work in the Provincial Court. Amendments to the Criminal Code on a variety of topics brought forth an entirely new spectrum of charges and defences. Provincial Court judges were being called upon to hear and determine issues of a very high order of complexity. Educational courses were necessary to keep the judges abreast of developments in the law and the educational conferences became more focused.”[38]

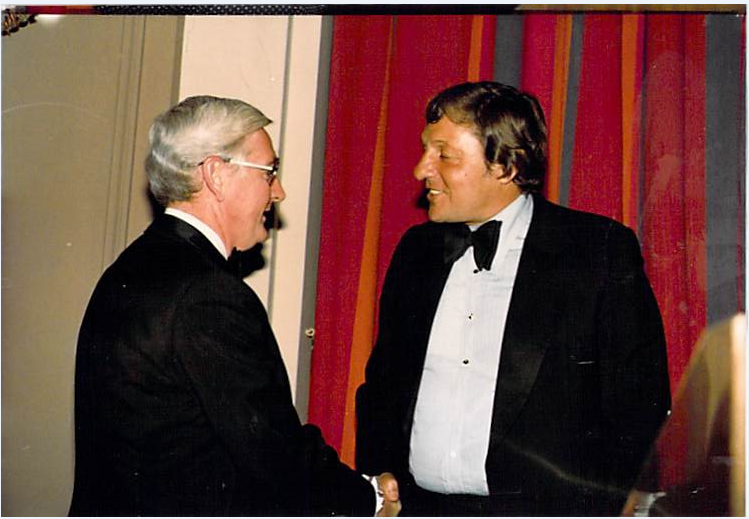

Justice Sidney Lederman was an early leader in the judicial education field when he was teaching at Osgoode Hall Law School. For Lederman, Hayes’ annual University Judicial Education Program at Western University in London, Ontario “may seem modest now but this was probably the first regularly scheduled education program for judges in Canada. Hayes was a real leader with this initiative.” [39] In the early days, this program was offered twice each June and one-sixth of the criminal bench was invited (so that every judge would attend once every three years). The judges felt obliged to participate and Hayes would call those who missed in their designated year to be sure they would be there for the next offering.

The basic format was a set of lectures, with time for questions and answers. The following is an extract from Hayes’ report on the June 1974 edition of this program, offering a good summary of the scope of the proceedings.

“This year groups will study various subjects such as witnesses, the Protection of Privacy Act, the admissibility of photographs, video-tape and voice prints, diminished responsibility, competence, parties to offences, identification, and other subjects.”[40]

The acknowledged judicial leader in criminal law, Court of Appeal Judge G. Arthur Martin, was a frequent lecturer. He would be joined by other judges from various courts along with academics who would present on all aspects of criminal law. In the 1980s, teaching methods started to expand beyond the simple lecture (“talking head”) formula to become more sophisticated and oriented specifically toward adult learners. For example, videos, as learning tools, were developed on subjects including qualifying an expert witness.

In the 1970s, the Provincial Judges Association of Ontario (Criminal Division) began offering, on a regional basis, four annual sentencing seminars that enabled judges to compare their sentences in simulated cases. Attendance was considered “obligatory”[41] by the judges. The seminars had the reputation for being simply exercises where each judge defended the perspective he or she brought to the fact situations that were presented.[42] John Hogarth and David Vanek were, however, equally critical of these seminars. According to Vanek, they simply “lapsed into a comparison of sentences for similar offences from locality to locality.”[43]

In his book, Hogarth pointed out the danger of this approach to education about sentencing practices.

“The content of courses and seminars for judges and magistrates must be carefully developed….Improperly handled, formal training can lead to the development of more sophisticated rationalizations for essentially punitive practices.”[44]

For this reason, Hogarth advocated using skills training, as opposed to what Vanek called lapsing into comparisons of sentences.[45] As Hogarth explained: “Training should not be directed solely to providing information about sentencing procedures or the content of institutional programmes available for offenders (as important as these matters are), but primarily to enhancing the perceptual skills, human sensitivity, and critical abilities of judges in handling information and in assessing the results of research concerning the effectiveness of different types of penal measures….This will undoubtedly make sentencing more complicated and difficult for them, but at the same time it is likely to create an atmosphere in which sentencing can be improved.”[46]

Vanek’s recollections reveal another great challenge the Court faced when developing educational programming – funding – or, specifically, the lack therof.

At the Association’s Annual Conference for criminal judges in 1974, when Vanek was chair of the Education Committee, he proudly reported on a proposed educational program “designed to give each Provincial Court judge an opportunity to observe hearings in the Court of Appeal for several days, and to participate in discussions” about the results of the appeals heard.[47] This program ran for several years but was cancelled due to lack of funding from the provincial government, Vanek later reported.[48]

This cancellation points to a major impediment to the development of much-needed educational programming. The government’s control of the budget left the Court without full control over the development and delivery of its education. Change on that front, however, was coming in the form of an historic memorandum of understanding in 1993.

As recently as the late 1980s, the primary “training” a new Criminal Court judge could expect still only involved shadowing a judge at Toronto’s Old City Hall for up to two weeks. A case in point: upon his appointment to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in 1986 to sit in Ottawa, Brian Lennox recalled travelling to Toronto for a stint of a couple of weeks at Old City Hall watching other judges do their work between the date of his appointment and his swearing-in. Lennox credits all of the Ottawa judges, led by then Senior Judge Paul Bélanger, with guiding him in his new role as a judge – and providing ample informal education to him.[49]

Lennox also recalled attending a week-long program in substantive law offered by the Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges (CAPCJ). This innovative program had been introduced in the 1970s for new appointees from all provincial courts across Canada but, as Lennox recalled, back in the 1970s and 1980s, not all new appointees from Ontario were given the opportunity to attend.[50]

Newly appointed judges were also given some instructional materials, including “The Conduct of a Trial” (a document Hayes developed and augmented in response to new developments in the law); a copy of the Criminal Code and a subscription to a criminal law case reporting service.[51] Circulation of pertinent materials improved when Allen Edgar joined the Court as Research Counsel in 1980. Edgar recalls that “The Conduct of a Trial” comprised approximately 75 pages when he began working with the Court. In the early 1980s, Hayes gave Edgar responsibility for updating the manual. “Now it is fatter and electronic – some 300 pages in length,” stated Edgar. “The judges call me with legal questions and, as a result, I know what revisions need to be made to ‘The Conduct of a Trial’ – it’s a synergistic process.”[52]

“Ontario had the best judicial education”

“My first brush with judicial education was in Ontario in the very early 1970s,” recalled Judge Sandra Oxner. Oxner, who later became a leader in her own right in the realm of judicial education in Canada, was appointed to the Provincial Court of Nova Scotia in 1971.“

I had just been appointed to the bench but they had no judicial education at all in Nova Scotia at that time. I went to Fred Haye’s Court to see his education program. Fred and Judge Cy Perkins were involved in developing the programs at that time. In those days, judicial education was an afterthought, not at all esteemed and there was no money for it in most provincial courts in Canada. Ontario, on the other hand, had the best judicial education for any provincial court at that time and that was because of Fred Hayes.”

The Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges was founded in 1973, with a key objective of promoting judicial education to all provincial court judges in Canada. Oxner became CAPCJ’s first education chair and patterned her initial efforts on those already established in Ontario. “In those early days, a lot of support for CAPCJ’s education programming came from Ontario.”

(Source: Interview of S. Oxner for OCJ History Project, 2014.)

Leadership of Family Division Educational Programming

Chief Judge Andrews, with the support of the Association of Juvenile and Family Court judges and individual judges, including Patrick Gravely, David Steinberg, and George Thomson, introduced the first education programs including some elements of what is now called experiential education. Andrews recruited Thomson to put together the first Judges’ Training Institute, which began in 1974 with three one-week programs offered to one-third of the family judges at each session. These programs involved many interactive elements, including analysis and discussion of the wide variations between amounts of spousal and child support awarded by judges, as well as a review of family assessment issues with Toronto Family Court Clinic psychiatrist, Dr. Clive Chamberlain.

The 1974 program also included opportunities to:

• visit a shelter for abused women;

• meet a person who had experience working with adolescents in Regent Park (then Toronto’s largest community housing project);

• eat dinner at a youth group home; and

• visit the Oakville Assessment Centre.

The 1975 program included viewing videos of mock family law proceedings followed by discussion of errors presented in the videos; identifying and resolving various evidence and ethics problems; debating truancy laws; and detailing alternatives to training school. Offered annually, thereafter, subsequent subjects of study included court administration issues such as caseload management, automatic enforcement of support orders and what a family court might look like in the future. The gradual move to planned, interactive judicial education with the Court had begun.

Justice Robert Walmsley played a significant role in judicial education after he became the Associate Chief Judge in the Provincial Court (Family Division) in 1978. He possessed an erudite outlook and advocated an eclectic approach to learning, which was always apparent in the programs he helped design.

In fact, Walmsley is credited as one of the pioneers in the area of “social context” education in Canada. “In 1985, at the invitation of Associate Chief Judge Robert Walmsley of the then Ontario Provincial Court, Family Division, the Ontario Women’s Directorate (OWD) delivered a full court programme on violence against women in relationships. Following the success of this programme, a second programme on women’s equality was also designed and delivered by the OWD to this court in March of 1987.”[53]

On the informal side of the education ledger, Andrews also brought in research counsel in 1974 to provide assistance to the family judges. Roman Komar[54] began collecting and circulating judgments and relevant statutes, as well as conducting research and producing valuable resource materials. His “Reasons for Judgment: A Handbook for Judges and Other Judicial Officers” was published in 1980. Chief Judge Andrews also expected newly appointed family judges to “learn by watching.” They were encouraged to sit and observe, for a couple of weeks, four or five judges whom Andrews recommended.

What is “Social Context” Education?

“What makes it possible for us to genuinely judge, to move beyond our private idiosyncrasies and preferences, is our capacity to achieve an ‘enlargement of mind.’ We do this by taking different perspectives into account. This is the path out of blindness of our subjective private conditions. The more views we are able to take into account, the less likely we are to be locked into one perspective….It is the capacity for ‘enlargement of mind’ that makes autonomous, impartial judgment possible.”

(Jennifer Nedelsky, “Embodied Diversity and the Challenges to Law” (1997), 42 McGill L.J., p. 107)In practical terms, this means that – as a step toward judicial impartiality – a judge should understand the factual and social context of a case. In fact, the law requires that context be taken into account by a judge. To this end, judicial education has developed in the area of “social context.”

Justice Donna Hackett of the Ontario Court of Justice has, in various roles, provided the judiciary in Canada with extensive guidance on the development of social context education.Here is her definition of that term:

“[S]ocial context education for judges entails the pursuit of at least four broad goals:

• increasing judges’ understanding of equality principles;

• facilitating enhanced recognition by the judiciary of the pervasiveness of disadvantage and inequality in modern society;

• challenging judges’ assumptions and the impact that such assumptions might have on the process of judicial decision-making; and

• demonstrating the relevance of the experience of diversity, (in)equality and (dis)advantage to the judicial function.”

(Donna Hackett and Richard F. Devlin, “Constitutionalized Law Reform: Equality Rights and Social Context Education for Judges” (2005) 4. J.L.&Equal.157, pp. 158-159. See also R. v. S. (R.D.), [1997] 3 S.C.R. 484)

A Summary of Programming for Judges Pre-1990 – And the Challenges of Moving Forward

“Until the merger (of the Courts) in 1990, the Family and Criminal Divisions each had separate jurisdictions, their own Chief Judges, and distinct education programs, which had been largely developed during the early years of their existence. Education programming was, in significant measure, the responsibility of the respective family law and criminal law judges’ associations in each of the two Courts.Programming within the Family Division consisted of:

i) a fall family law meeting;

ii) an intensive week-long program (created by Chief Judge Ted Andrews) known as “The Judicial Development Institute” in January; and

iii) a third seminar in the spring.

Within the Criminal Division, there were also three education programs:

i) a series of virtually identical regional criminal law seminars held in the fall in each of four regions;

ii) the annual spring meeting of the Court; and

iii) a one-week intensive criminal law program created by Chief Judge Fred Hayes and presented each summer in a university setting.

The challenge at the time of creation of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) was to preserve the benefits of strong programming that had been provided both in criminal law and in family law within a reorganized and newly created Court. It was also important that the judges’ associations, both criminal and family, retain their preeminent role in the development and presentation of judicial education.”

(David Wake and Brian W. Lennox, “The Ontario Court of Justice: A Journey in Education,” National Judicial Institute: 20th Anniversary Essays, p. 41)

Justice of the Peace Educational Programming

There is no better description of the education (or lack thereof) that justices of the peace received than the following passage in Professor Alan Mewett’s 1981 report to the Attorney General concerning the then sorry state of Ontario’s justices of the peace.

If we were to look only at the formal provisions made for the training and continuing education of Justices of the Peace in Ontario, the position could only be described as appalling. In practice, one sees that it is less appalling than quite unsatisfactory.

On appointment, a justice will receive a binder containing material relevant to his office. This will include extracts from the relevant portions of the Code, the Provincial Offences Act, the Provincial Courts Act and so on, together with written material explaining some of the provisions. He may also be given a copy of the Criminal Code. He is expected either to be or to become familiar with these so as to have or acquire a working knowledge of what is expected of him. That is all the express formal training – if it can be so designated – that is provided for a new Justice of the Peace and the only “education” that he receives. But this only tells a very small part of a real story. While the Ministry has made sporadic efforts to provide training and educational seminars for Justices of the Peace, these have been few and far between. Not all Justices were invited to attend them, and some of those invited did not appear.

As a result, the burden of training and educating Justices of the Peace has fallen, of necessity upon the Provincial Court Judges and the Justices of the Peace themselves. In some localities, the Crown Attorney has also volunteered his services in this area. There is no consistency. Most Provincial Court Judges are acutely aware of the need to have their local Justices of the Peace properly trained and able to function intelligently. They will take the time to observe them, offer them advice and help. In the large urban centres, where conditions warrant it, a more formal program can be arranged. The Ontario Justice of the Peace Association has done its best, with limited resources, to arrange work-shops and discussion programs. The Toronto Justices of the Peace Association (separate from the Ontario body) also holds meetings and seminars. In some localities, a newly appointed Justice of the Peace will undergo an ‘apprenticeship’ period of sitting in or observing more experienced Justices of the Peace.

As a result, one can only conclude that the actual training and education of Justices of the Peace in this province range from virtually non-existent to the barely acceptable, depending upon the location. Clearly, steps must be taken to remedy this situation.[55]

Chief Judge Hayes became responsible for the justices of the peace upon his appointment as Chief in 1972. He recognized there were major problems with the lack of training provided to them, but the government made few funds available. This left Hayes scrambling to find the most basic materials for the justices of the peace.

Hayes made a huge, courageous and enduring contribution to education of justices of the peace in one critical area – Aboriginal appointments to the bench. Ontario’s Native Justice of the Peace Program owes its existence to Hayes – and the prodding of Alan Mewett.

Delivered to Attorney General Roy McMurtry, Mewett’s report on the office and function of justices of the peace included a separate set of recommendations concerning Native communities and remote areas. Mewett commented upon the relative absence of Native people from the ranks of justices of the peace.[56] One of Mewett’s suggestions to remedy this situation was a three-to-four-week “pre-appointment” education program tailored to Aboriginal candidates for the position of justice of the peace.[57]

Hayes acted on Mewett’s recommendations. The Native Justice of the Peace Program has been called “remarkable in its grass-roots foundation and its audacity.”[58] Retired Justice Gérald Michel and Doug Ewart (director of the Policy Development Division of the Ministry of the Attorney General when the program was introduced) share identical memories of Hayes’ actions. According to Ewart , “At a time of widespread discrimination, and well before significant numbers of aboriginal people entered law schools and joined the legal profession, this program provided the first sustained and supportive educational program to bring aboriginal people into presiding positions in Ontario’s courts.”[59]

“The aim was to have aboriginal people working in the courts where there was a concentration of aboriginal people, so they could feel part of the system…and to better serve the justice system in the isolated communities where people had no one to turn to for private complaints….The aim was also to train Justices of the Peace who would preside over minor offences under the reserve band by-laws and hear other provincial regulatory offences…”[60]

How did Hayes accomplish this feat? “The program worked with and within aboriginal communities,” explained Ewart. “People were identified who, while lacking formal qualifications, clearly had the intelligence, integrity and judgment that would make for a fine judicial officer. Instead of letting the lack of justice-system knowledge or other formal qualification bar them from such positions, Hayes instituted an education program that provided intensive, in-person, pre-appointment training so those gaps could be filled, and fully qualified individuals could be considered for appointment.”[61]

To make all this happen, Hayes made three crucial appointments to guide the program: Justice of the Peace Richard LeSarge (who became the Senior Justice of the Peace Responsible for the Ontario Native Justice of the Peace Program in 1994), Judge Gérald Michel, and Stan Jolly, an advisor with the Ministry of the Attorney General.

They were later joined by others, including Judge Gerald Lapkin[62], appointed the Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace in 1990, and Shelley Howell,[63] who became research counsel serving the justices of the peace, in 1991. This group developed a manual of course material that was taught during programs of two-to-four-weeks duration across the province. Most days in these programs concluded with a test to assess the degree of comprehension of the material, recalled Michel.[64]

A Glimpse at the Success of the Native Justice of the Peace Program

The 1988/90 Annual Report of the Ministry of the Attorney General documented the tangible success of the program:“The Ontario Native justice of the peace program…encourages and enables native citizens to play an expanded role in judicial proceedings. To date, five full-time and almost 20 part-time Native JPs have been appointed under the program.”

This innovative program had two significant outcomes.

1. Eventually, Ontario was served by a good number of excellent Aboriginal justices of the peace.

2. A body of educational materials was developed, together with an approach to teaching not only pre-appointees but also newly appointed justices of the peace. By the mid-1990s, this material and approach became part of the introduction all newly appointed justices of the peace received before assuming full responsibilities for sitting – Aboriginal or otherwise.

Despite Hayes “audacious” move to introduce the Native Justice of the Peace Program, progress was generally slow on the broader education front. Even after the scathing comments delivered by Mewett in his 1981 report, the government was tardy in acting on his call for the situation to be “remedied.” Not until 1989 did the government, led by Attorney General Ian Scott, begin to respond – in the form of the Justices of the Peace Act, 1989, which created the Co-ordinator position that Lapkin filled in 1990. Ultimately, development of an education plan for the justices of the peace became mandated as a statutory requirement in 2002.

The Native Justice of the Peace Program – “Very Gratifying”

Gerald Lapkin recalled his involvement with the Native Justice of the Peace Program as follows.

“We took people with absolutely no involvement with or knowledge of the justice system. We invited people who were part of the community – respected by the community, not just “fly-in” people – they were members of the community. We trained them and it was very intensive. And it was very gratifying when they became justices of the peace.

The first time I went to swear someone in it was in Attawapiskat. I went up there as much for the community as for the new justice of the peace. Richard Le Sarge said this is a big deal. We rented the local town hall, and they put on a feast of traditional foods afterwards…. At another swearing in at a remote community, Richard Le Sarge, Stan Jolly, a local judge and I landed at an air strip, three miles from town. Nobody shows up. Finally, Richard flagged down a passing pick-up truck. We sat in the back of the open truck and put on our gowns as we were driving. When we pulled into town, everyone was waiting. The guy who was supposed to pick us up said: ‘I thought about picking you guys up, but I didn’t want to be late for the swearing in!’”

(Interview of Gerald Lapkin for OCJ History, 2014)

Societal and Judicial Recognition and Acceptance of Adult Education: Judicial Education Becomes a National Priority

Adult education is now an integral part of nearly every professional career. It’s easy to forget this is a relatively recent phenomenon. Although people have always learned “on the job” in an informal fashion, continuing formal education aimed at adults in the workplace was rare until the mid-1950s.[65] The history of judicial education in the Ontario Court of Justice mirrors what was happening in broader society.

What began as court-based programming, primarily at the provincial level, slowly became broad-based support for judicial education for all judges in Canada. Several organizations, all born in the 1970s and 1980s, focused on judicial education and had a significant influence on the development of education programming for the Provincial Court. That influence continued well into the 1990s and beyond. These organizations included:

• The Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges;

• The National Association of Family Court Judges;

• The Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice; and

• The Western Judicial Education Centre.

The Origins of Canadian Organizations Devoted to Judicial EducationThe work done at each of these organizations influenced the development of the approach taken by the Ontario Provincial Courts – both criminal and family – to judicial education.

- The Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges (CAPCJ)

On May 4, 1973, under the leadership of Magistrate Lloyd Hicks from Newfoundland and with financial support from the federal government, CAPCJ was formed. This federation of provincial and territorial judges’ associations grew to include most of the thousand-plus provincial and territorial judges in Canada. One of its aims and objectives was: “To enlarge and perfect the knowledge and understanding of Provincial and Territorial Court Judges of the judicial function, by meaningful research and continuing education in various aspects of the law.”Sandra Oxner, then a judge of the Provincial Court of Nova Scotia, was CAPCJ’s first education chair (“The only reason I was given education to do was that nobody wanted it.”) and became its president. In addition to instituting regional seminars, she led the development of the first course for newly appointed judges in Kingston, Ontario in November 1976; a ten-day program, ultimately shortened to a week. It was the first such program in Canada and remains an essential introduction to the work of provincial and territorial court judges.At the time of the introduction of the new program, Ontario’s Criminal Court judges had joined CAPCJ but the Family Court judges had not. However, Ontario Family Court judge, George Thomson, developed the family law programming at this historic first course for new judges in Canada.CAPCJ holds a national annual conference that includes a substantial education program. Many Ontario Court of Justice judges have taken leadership roles in developing educational programming for CAPCJ.(Source: Interview of S. Oxner for OCJ History Project, 2014.)

- The National Association of Family Court Judges

Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division), Ted Andrews, was eager to create an association of Family Court judges across Canada to build support for these courts, promote judicial education for its judges and to advocate for a Unified Family Court. With a federal grant, he organized the first meeting of the association and it promoted family law education programming over the next decade. Ontario Family Court judges resisted joining CAPCJ until steps were taken in the 1980s to reassure them that CAPCJ would accommodate a focus on family law in its programming.

- The Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice (CIAJ)

In 1974, the CIAJ was formed as a multi-disciplinary organization to link individuals and organizations active in the administration of justice. Judicial education was one of its mandates and when the federal judiciary was initially resistant, the organization turned to the provincial courts and joined with CAPCJ to develop its first regional and new judges’ programming. Later, CIAJ developed the first program for newly-appointed superior court judges and, perhaps most important, introduced the first skills-based education program for judges in Canada, with its now long-running program on judgment writing. The CIAJ has worked with the National Judicial Institute on many programs, including a seminar for longer-serving judges.

In 1974, the CIAJ was formed as a multi-disciplinary organization to link individuals and organizations active in the administration of justice. Judicial education was one of its mandates and when the federal judiciary was initially resistant, the organization turned to the provincial courts and joined with CAPCJ to develop its first regional and new judges’ programming. Later, CIAJ developed the first program for newly-appointed superior court judges and, perhaps most important, introduced the first skills-based education program for judges in Canada, with its now long-running program on judgment writing. The CIAJ has worked with the National Judicial Institute on many programs, including a seminar for longer-serving judges.

- The Western Judicial Education Centre (WJEC)

WJEC was a later entry into the field but an important initiative at the provincial court level, led by Judge Douglas Campbell of the Provincial Court of British Columbia. It was the first judicial education program to concentrate on social context education for judges, using innovative, experiential programming and involving those from the community who brought special experience and expertise to the programs offered. It worked closely with the Provincial Courts in the delivery of social context education in 1991.

Over the years, these organizations co-operated in various combinations to develop and deliver many different education programs in partnership. This focus on judicial education culminated in the formation of the National Judicial Institute  (NJI) in 1988, with the strong support of the then-Chief Justice of Canada, Brian Dickson. The NJI was founded with modest financial support from the federal government and many of the provinces, including Ontario. From its inception, two provincial court representatives have sat on the NJI Board of Directors, one from the Council of Chief Judges and one identified in consultation with Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges. Chief Judge Hayes was one of the first board members. He was followed in that position by Judge Charles Scullion. Although there was a desire to serve all courts in Canada, little early programming was offered that provincial court judges could or did attend. Although the method of securing funds for new courses guaranteed that the NJI initially almost exclusively served federally appointed superior court judges, that emphasis was to change – and another transformation was set to begin for judicial education in Ontario.

(NJI) in 1988, with the strong support of the then-Chief Justice of Canada, Brian Dickson. The NJI was founded with modest financial support from the federal government and many of the provinces, including Ontario. From its inception, two provincial court representatives have sat on the NJI Board of Directors, one from the Council of Chief Judges and one identified in consultation with Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges. Chief Judge Hayes was one of the first board members. He was followed in that position by Judge Charles Scullion. Although there was a desire to serve all courts in Canada, little early programming was offered that provincial court judges could or did attend. Although the method of securing funds for new courses guaranteed that the NJI initially almost exclusively served federally appointed superior court judges, that emphasis was to change – and another transformation was set to begin for judicial education in Ontario.

The Transformation Takes Root: From 1990 Onward

“The legislation…will require the Chief Judge to establish a plan for judicial education. These reforms will give the Ontario judiciary additional tools to continue their professional development and to maintain their high professional standards. This will help to ensure that Ontario’s justice system remains one of the finest in the world.”[66]

These are the words of Attorney General Marion Boyd when introducing the Courts of Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 1993 on July 7, 1993. The justices of the peace would see a similar commitment to formal education in 2002, when the Justices of the Peace Act was similarly amended to provide a requirement for a plan for the continuing education of justices of the peace.[67]

These legislative changes were but one aspect of a transformation in judicial education. The amendments to the Courts of Justice Act did not stand alone. They were accompanied by a radical set of new tools guaranteeing formal education programming for all Provincial Court judges. Those tools included – among other provisions – new funding arrangements with the provincial government and new partnerships with various judicial education organizations, including CAPCJ, WJEC and NJI.

Education for Judges

Creation of the New Court

Work to improve the continuing education program was under way in the early 1990s when the family and criminal divisions of the Provincial Court became a single court: the Ontario Court (Provincial Division).[68] Sidney Linden was appointed the first Chief Judge of that newly constituted Court and very quickly learned that the Court had very little control over the realm of education.

“Just after my appointment, I heard about a French language training program that was taking place in Quebec. I read the material for the program and decided that it would be a great program for our judges, very practical stuff. I wanted to send several of our bilingual judges to attend the program and I assumed that this was just a matter of informing the Ministry and our judges would be off and on their way. How wrong I was! I received a call from the deputy minister and I can still hear him saying: ‘Oh, no, no, no. We can’t send your judges off to Quebec. It can’t be done. It’s far too extravagant and you have no budget for that. We might be able to afford to send one judge, but that’s it. And by the way, that decision is not yours to make, it’s ours.’ Of course he meant that it was the Ministry’s decision. I hung up the phone and asked myself: ‘Am I the Chief Judge of this Court or is the deputy minister?’ The answer was clear – at that point in time, the deputy minister was in charge.”[69]

Determined to rectify this situation, Linden approached the provincial government and suggested the creation of a memorandum of understanding between the Court and the Ministry of the Attorney General. This was the first of several such memoranda the Court signed with various parties and which served to enunciate the Court’s approach to education (along with many other Court-related issues.)

An Innovative Experience: Gender Equity Education, 1990-1991

From the time of his appointment to the bench in 1986, former Chief Justice Brian Lennox was involved with education programming. As he describes it, the approach to education – particularly for criminal judges – began to shift dramatically in the early 1990s, when the Court began working with the Western Judicial Education Centre (WJEC).

“The Provincial Court (Criminal Division) had been pretty complacent about its education programming, based on the assumption that we were the biggest and best criminal court in Canada and accordingly must have the best education programming. The complacency that arose from that assumption was shattered by the Court’s work with WJEC on Gender Equity in 1990 and 1991. The preparation for the program was meticulous, the materials (research, documentation, videos) were something we had never seen. The concept of training the trainers was entirely new for us and the extensive collaboration with academics, experts and the community was unprecedented. Without criticizing those who had gone before within the Court (and who often lacked the training, time, experience and resources), it became obvious that truly valuable judicial education required far more time and resources than we had ever been able to put into it.”

As former Chief Justice Sidney Linden recalled, this gender equity education arrived at a particularly important moment in the Court’s history. “It was the first time we put our toes into social context education and it was also the time when the Ontario Judicial Council had received complaints about the conduct of Judge Walter Hryciuk.” These complaints involved Hryciuk’s alleged sexual assault and harassment of female Crown Attorneys and court staff. (Hryciuk was ordered removed from the bench in 1993 after an Ontario Judicial Council Inquiry into the sexual misconduct allegations, but was later vindicated in 1996 by the Ontario Court of Appeal after it ruled the Inquiry judge unfairly allowed new misconduct complaints to be added to the Inquiry. Hyrciuk did not return to the bench following the Inquiry and retired in 1998.)

“When I saw what WJEC was doing with gender equity education, I came back and said ‘We have to do this in Ontario.’ At that time, our Court did not have control over our own education budget and I persuaded the Ministry of the Attorney General to give us the money to offer this critical program. I was so proud that we could deliver this high quality of education,” recalled Linden.

The experience of working with WJEC made the Court rethink the educational programming as a whole. It also helps explain the later decision to form a closer relationship with the NJI once that organization embraced this method of designing and developing skills-based, experiential education.

(Sources: Interviews of Brian W. Lennox for OCJ History Project, 2014-15; Interviews of S. Linden for OCJ History Project, 2014-15; David Wake and Brian W. Lennox, “The Ontario Court of Justice: A Journey in Education,” National Judicial Institute: 20th Anniversary Essays, p. 41)

Impact of the Memorandum of Understanding Between the Court and the Ministry of the Attorney General

The memorandum of understanding between the Court and the Ministry, first signed in 1993, transferred to the Chief Justice’s office both the budget and responsibility for the content of judicial education for judges and justices of the peace. More than that, it transferred funding for a number of other functions and provided the Chief Justice with enough flexibility in the Court’s budget to enable the Court to identify and prioritize areas of particular importance.

Requirement for a Continuing Education Plan for Judges – Courts of Justice Act

This provision was introduced into the Courts of Justice Act in 1994 – a formal recognition of the necessity of continuing education for provincial judges in Ontario.

51.10 (1) The Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice shall establish a plan for the continuing education of provincial judges, and shall implement the plan when it has been reviewed and approved by the Judicial Council.

Duty of Chief Justice

(2) The Chief Justice shall ensure that the plan for continuing education is made available to the public, in English and French, when it has been approved by the Judicial Council.

Goals

(3) Continuing education of judges has the following goals:

1. Maintaining and developing professional competence.

2. Maintaining and developing social awareness.

3. Encouraging personal growth.

A New Governance Model and Another Memorandum of Understanding

A New Governance Model and Another Memorandum of Understanding: Chief Judge Linden’s first task was to develop a governance model that balanced the obligation placed on the Chief’s office with the established role of the two associations of judges – the Ontario Provincial Judges Association (Criminal Division) and the Ontario Family Law Judges Association – and ensured their support for the memorandum of understanding as a whole. (These two associations merged in May 1999 to become the Ontario Conference of Judges.) To accomplish this, a separate memorandum of understanding was developed with the two associations and, subsequently, the Ontario Conference of Judges. This document served to rationalize the education program for the Court and reaffirm the important role of the Conference in developing the regional and annual meetings and determining the content of the core education programming.

Creation of the Education Secretariat

The memorandum of understanding between the associations also formally recognized the creation of the Education Secretariat – “a body responsible for overall education policy and funding associated with judicial training” for the Court.[70]

Two former chairs of the Education Secretariat – former Chief Justice Brian Lennox and former Associate Chief Justice David Wake – provided a concise history of the development of the Secretariat over its life.

The “body included representatives from both judges’ associations (family law and criminal law)….Initial discussions at the Secretariat were related to the timing of judicial education programs and general curriculum issues, but quickly became more substantive….The mandate of the Secretariat was to coordinate education policy and programming for the whole Court, and it became increasingly active in programming.”[71]

The role of the Secretariat was further explained by Linden in 1999 as follows. “It administers an annual budget for education and allocates that budget among education programs which are either organized by the associations for the judges of the Court or otherwise offered to the judges. Core education programs are developed and presented by the judges’ associations.”[72] Further, it was the responsibility of the Education Secretariat to maintain the statutorily mandated education plan.

What is “Core” Education for the Judges?

The programs presented by the Education Secretariat and the Ontario Conference of Judges constitute the Core Program of the Ontario Court of Justice education curriculum. The Ontario Conference of Judges selects a chair of criminal law education and a chair of family law education. The two chairs in turn may create a support committee to advise and assist them in putting together the core education programs. Part of the core programming is offered annually and part of it is presented “as needed.”

1) Annual Core Programs

Seven family and criminal programs are presented each year with a changing curriculum to reflect the educational needs of the Court. These courses are open to every criminal and family judge in accordance with their area of practice.

2) “As Needed” Recurring Programs

These are programs presented annually or biannually with limited enrolment. They fulfill a variety of education needs such as the development of judicial skills and leadership and social context training. Examples of these “as needed” programs have included programming on the following topics:

• Social context,

• Judicial leadership and administration,

• Communication skills,

• Computer training, and

• Preparation for retirement.

For further details, see the Ontario Court of Justice, “Continuing Education Plan” published on the Ontario Court of Justice website and attached as an appendix to this essay.

According to Justice David Wake, who chaired the Secretariat from 1999 to 2005, it has faced a number of challenges over the years, including: continuing uncertainty about the different roles of the Conference and the Office of the Chief Justice; concern about possible erosion to the core programs; lack of coordination between the different programs; and the ongoing worry of the family law judges that their unique programming needs might be lost as their numbers declined with the expansion of the Unified Family Court.[73] The Secretariat has struggled with long-term planning. However, it has also overseen a remarkable expansion in continuing education that has benefitted not only the Court itself but also affected the quality of education available to provincial court judges across Canada – as a consequence of having shared many of its resources with other provincial courts over the years.

| The Court’s University Program, 1998-2006

Justice Elliott Allen served as the leader of the Court’s University Program, originally established by Fred Hayes, Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in the 1970s. These are his reminiscences of volunteering on this program from 1998 until its end in 2006. As a 1991 appointee to the Court, I never had the opportunity to attend the original University Program which had been established in the 1970s for criminal judges by former Chief Judge Fred Hayes. I got involved in judicial education around 1995 and, in 1998, was asked to run a week-long session at the Windermere facility on the north edge of the Western campus in London. This version of the University Program had been designed for the judges of our Court by Justice Don Fraser, and Professors Allan Manson, Don Stuart and Ron Delisle (all from Queen’s Law School), among others under the direction of then Associate Chief Justice Brian Lennox. Its focus was criminal law – and the thought was that all criminal law judges would attend at some point during their careers on the bench. Justice Greg Pockele was the “site convenor.” The Court’s research counsel, Allen Edgar, was a perennial presenter and resource. The new program reflected the “disciplined” approach to program design being promoted by the National Judicial Institute, and included social context education, which followed on the heels of the gender equity and “Court in the Inclusive Society” programs earlier in the decade. Before going any further, I must recognize the huge contribution to the program by Professor Allan Manson. He presented every year I was involved with the program. He recruited speakers, most notably the brilliant and dependable Professor Dale Ives from Western University. Manson always had a lecture in his back pocket to fill in if the scheduled speaker didn’t show. He was one of the main reasons the program became a bit of a salon for academics, with the discussions at mealtimes being as educational as the classes. The program ran from Monday morning to Friday lunch, with Wednesday afternoon off. There were generally between two and three dozen judges in attendance each year. We had a fabulous bright room for the sessions, with windows and glass doors the full length on both sides. To give you an idea of the types of presentations we heard: the opening session on June 8, 1998, was delivered by Professor Stuart on the law concerning the rape shield and honest belief. We went on to deal with domestic violence, and Charter issues, evidence and sentencing issues. That was followed by a presentation by Professor Connie Backhouse on the role of race, class and gender in the history of our criminal law. That year, Justices Sally Marin, Jim Blacklock, Saul Nosanchuk, Paul Megginson, Gilles Renaud and Greg Pockele assisted with presentations, a practice of peer-led education that continued throughout the life of the program. The University Program evolved over the years. Some things worked better than others, and the program had to be completely new every three years. The practice was that judges were offered the opportunity to attend every three years – so that meant a rework of the program on a three-year cycle. We attempted to respond to the needs of the bench by including current issues in social context education as well as black letter law. Presenters included notable academics, judges and practitioners from across Ontario and Canada. They included Professors Julian Roberts, Lorne Sossin, Lee Stuesser, Tony Doob, Justices Gary Trotter, Patrick Healy, the beloved Marc Rosenberg and many others. Professors Scot Wortley and David Tanovich presented on racial profiling. A pre-appointment Diane Oleskiw (now a member of our Court) achieved a huge “aha” moment for the group on the admissibility of third party records. Dale Ives, in the first of many presentations precipitated one of the hottest debates ever with an aside about how she didn’t have much use for the right to silence. Jim Blacklock was in his element listening to Professor Richard Devlin tell us why we should study jurisprudence. Professor Alan Leschied told us about the actual outcomes of our youth sentencing practices. I can’t begin to cover the vast array of sessions and presenters who made the University Program what it was. Most of the criminal law bench attended, some at every opportunity. The program functioned as a “working conversation,” with full participation of all those present in the sessions and in small problem-solving breakout groups. I was blessed with a free hand to modify the program on an ongoing basis. I became friends with some of the great criminal law thinkers of our time. It was an education volunteer’s dream. When I later took up teaching at the University of Guelph, all five authors of the textbook I used in my course on sentencing had previously presented at the University Program. While I worked with a free hand, I recognized that I was building on a long tradition. From the 1970s onwards, the University Program was continued and improved under a series of different judges of the Court, including Judges Cy Perkins, Russell Merredew and Douglas Walker. Judge Brian Lennox was given responsibility for the University Program by Chief Judge Hayes in 1988. I took over from then Associate Chief Judge Lennox in 1998 and worked with Associate Chief Justice David Wake after 1999. Following the 2006 session, the program was put on hold as the Court under then ACJ Annemarie Bonkalo began offering the opportunity to increasing numbers of judges to attend a new “Judges to Jail” program, designed to introduce judges to the corrections system. “Judges to Jail” was presented in the time slot customarily reserved for the University Program and was also university based, with the venue switching to Kingston and Queen’s University. Regrettably, for reasons having largely to do with the changing demographic of the bench and the increasing opportunities to attend the “Judges to Jail” series, the University Program ended. The University Program, which Hayes created and cultivated, served the criminal law judges well over its lifetime. In the process of evolution from the judicial education programming of the 1970s onwards, the University Program operated as an essential transition point and a proving ground for the dynamic, experiential judicial education of the modern Court. I will close with a memory of our very last session on June 16, 2006. Justice Tom Cromwell was still on the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal – he has since moved to the Supreme Court of Canada. I had no need to introduce him before he presented on the law of hearsay evidence and on the expression of findings of credibility, because he greeted everyone at the meeting room door, introducing himself to those he hadn’t met at the barbeque the night before in his customary humble and engaging manner. We hung on his every word – and learned. We had a good run. |

Groundwork is Laid for Strong, Consistent Support for Judicial Education

With the establishment of the Education Secretariat and the requirement for an education plan, the stage was set for a more coordinated approach to formal education – and that is what occurred. While it was modifying its own educational structure, the Court began to work – tentatively – with the NJI.

Involvement of the National Judicial Institute

In the early 2000s, the NJI began to expand its curriculum significantly. It continued an important new focus on social context education while moving to a model of education emphasizing experiential, skills-based learning. To make NJI seminars and materials accessible to provincial court judges, attendance at NJI programs was opened to provincial court judges who would pay only their expenses and a fee to cover the added costs for materials and food at the program. In addition, the NJI made its course materials and other resources freely available for use in court-based programming. Provincial judges were given access to the new, online courses and they became the most active students in these courses.

All of these developments encouraged the Court to formalize its relationship with the NJI – with another memorandum of understanding, signed in 2000 – and the NJI began providing substantive, pedagogic and logistical support. The key to the involvement of the National Judicial Institute was that the Court and its judges retained control over education and programming, while the NJI served in a significant advisory capacity.[74]