Introduction

Judicial Independence in its Infancy: 1867-1967

Judicial Independence Becomes Defined for the Provincial Courts: 1968-1989

The Story of R. v. Valente

The Pace Picks Up – A “Renaissance for the Court”: 1990-1999

The Court’s Structure Reflects Judicial Independence: 2000 and Onwards

Conclusion – What Does the Future Hold for Judicial Independence?

The expression “judicial independence” is both contextual and evolving. The definition of judicial independence is different now than it was one hundred, fifty or even twenty-five years ago and will undoubtedly continue to evolve into the future.

Brian W. Lennox, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice

Introduction

It is a well-accepted principle that judicial independence is vital to a democratic society. At its core, judicial independence is about judicial impartiality. Judges must be neutral when they adjudicate disputes between parties. They must not be beholden to any of the parties in the disputes that come before them, including (and especially) the government.

As former Attorney General Roy McMurtry has written: “If a government could count on the courts to enforce legislative and executive actions unauthorized by law, the individual citizen would have no protection against tyranny.”[1] But this doesn’t mean that judges can do whatever they want. The judges and justices of the peace of the Ontario Court of Justice are constrained in their behaviours by the law and the oaths of office all of them swear when they are appointed to the bench.

This “well-accepted principle,” however, was not always so well accepted or well defined. The road to the current understanding of judicial independence was long, torturous and hard fought – and not without a few casualties along the way.

Judicial Independence in its Infancy: 1867-1967

Introduction

The Ontario Court of Justice is the descendent of local courts that dotted the province. By 1967, this loosely organized group of courts was staffed by an array of magistrates, justices of the peace and juvenile and family court judges. “A fractured mosaic of individual fiefdoms” is how these courts have been described.[2]

While the concept of judicial independence was recognized, the Court’s early history amply demonstrates that it was not always well respected or considered.

Appointments to the bench occurred where the size of the local population warranted it. Early judicial officers, although appointed by the provincial government, were paid by local municipalities – often on a fee-for-service basis. In certain instances, magistrates and justices of the peace were paid only on conviction of the person before them. Appointments were often patronage plums – blatant rewards from politicians.[3]

Originally, senior police officers presided as magistrates in Police Magistrates’ Courts. Police officers laid a criminal charge against a person and then that person went to court where another police officer decided his or her guilt or innocence. This did not contribute to the image of the magistrate being in any way separate, impartial or independent from the police.[4] It was not until 1934, that the court was renamed Magistrates’ Court.[5]

This collection of courts and judicial officers sat on the lowest rung in the judicial hierarchy. Judges appointed by the federal government – superior court judges – have historically possessed constitutional guarantees of independence, enshrined in the British North America Act. Superior court judges cannot be dismissed because the government disagrees with their decisions. Provincially appointed magistrates, family judges and justices of the peace, on the other hand, had no such constitutional guarantees of judicial independence. They were members of statutory courts – courts created by provincial statutes as opposed to being enshrined in the Constitution. For these statutory courts, the concept of judicial independence was “largely undefined”[6] until well into the 1990s.

In the early days of the Ontario courts, that lack of definition of judicial independence was readily apparent as the 1920s tale of the “whisky ring scandal in Dunnville” reveals.

The Whisky Ring Scandal in Dunnville

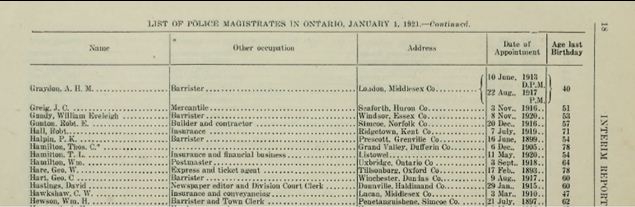

David Hastings served as a police magistrate, editor of the local newspaper and active politician – all at the same time – in Dunnville, a small town near Lake Erie. In 1920, William Raney, Attorney General and ardent member of the temperance movement, decided to suspend Hastings as magistrate. Hastings’ misdeed? He was vocally opposed to prohibition – he’d said as much in his courtroom and was not enforcing The Ontario Temperance Act, which forbade the purchase and sale of alcohol, to Raney’s satisfaction. Further, there were allegations that Hastings was too friendly with certain members of the Dunnville “whisky ring,” which was bringing illegal liquor into the town.

The clash between Raney and Hastings – which ultimately resulted in Hastings’ forced resignation from his position as magistrate – serves as a vivid backdrop to illustrate the ways in which judicial independence has evolved over the past 100 years for provincially appointed judges and justices of the peace in Ontario.

When it came to Raney’s attention that Dunnville was awash in drunk and disorderly citizens and vendors of liquor – who went unpunished in Hastings’ courtroom – Raney promptly sent a letter in July 1920 to all police magistrates in Ontario telling them “to administer The Ontario Temperance Act fully and effectually, and not to regard the enforcement of the law as simply a requirement of revenue but as a deterrent and preventive.”[7]

On receipt of this letter, Hastings began corresponding directly with Raney, complaining about the legislation, suggesting it was impossible for him to administer and enforce it in a small town like Dunnville. Raney responded by letter in November 1920, curtly informing Hastings that he was suspended from his position as magistrate but “if you prefer to announce your resignation please wire me promptly upon receipt of this letter.”[8]

Raney was within his rights to suspend Hastings in this summary fashion. At that time, the Magistrates Act “stated that every Police Magistrate… shall hold office during pleasure.”[9] If it pleased Raney to “fire” Hastings, he was entitled to do that.

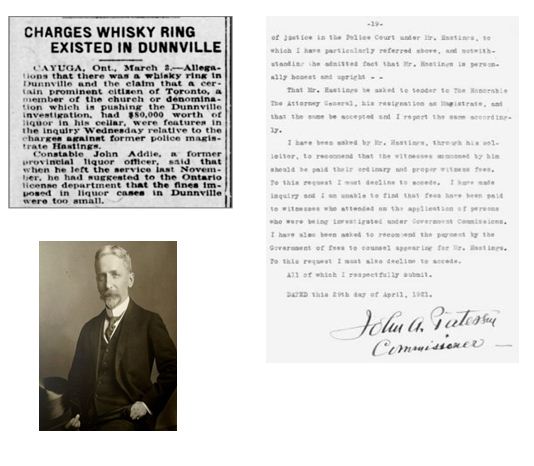

A Public Inquiry into Hastings’ Conduct as a Magistrate

Hastings declined to resign and instead published Raney’s letter to him in the Dunnville newspaper (recall that Hastings served as its editor) and asked for an investigation. A public inquiry was called to determine whether “the administration of justice in the Police Court at Dunnville has ceased to command public respect, and for this condition of things the Magistrate, Mr. Hastings, is largely responsible.”[10] Raney was under no legal obligation to call this inquiry. In fact, the legal necessity for such a process did not exist until an – amendment was made to the Magistrates Act [11]

Part of the inquiry’s task was to investigate Hastings’ close relationship to a group of men “in the control and domination of the affairs of the community,” and allegedly operating the illegal “whisky ring” in Dunnville.

The commissioner of the inquiry, a lawyer, John Paterson, found that Hastings was “personally honest and upright,” but nevertheless recommended that Hastings resign his position as magistrate.

In coming to his conclusion, Paterson depicted the group of Dunnville farmers selling liquor as cultivating the “Garden of Eden, being tempted” and shamefully falling. [12]According to Paterson, in those liquor cases where Hastings had convicted, he wrongly imposed the lowest possible fines. Paterson then took it upon himself to virtually retry Hastings’ cases involving The Ontario Temperance Act, reviewing the evidence, and arriving at opposite conclusions, finding men that Hastings had discharged should have been convicted of multiple liquor offences. “I do not presume to act as a Court of Appeal… but, sitting as a Commissioner, I can quite understand how such a disposition of this case could create a want of confidence in the Magistrate, and I venture to say that in my own opinion it also creates a want of confidence.”[13] Paterson concluded that Hastings was no longer a “useful” magistrate and, therefore, it would not be in the best interests of the administration of justice to keep a magistrate as “inefficient” as Hastings.[14] Hastings subsequently resigned – and the flow of liquor into Dunnville fell by two-thirds.[15]

The Evolution of Judicial Independence

“Justitia,” concluded Paterson, “must be beyond suspicion.” While that ideal has not changed since the 1920s, virtually every other aspect of the concept of judicial independence has – in practical terms – evolved into something very different than in Hastings’ day.

This comes as no surprise. As former Chief Justice Brian Lennox has written: “the expression ‘judicial independence’ is both contextual and evolving. The definition of judicial independence is different now than it was one hundred, fifty or even twenty-five years ago and will undoubtedly continue to evolve into the future. It is not a uniform standard…. In its most basic expression, however, judicial independence has always referred to the necessity that judicial decision making be free from external pressure or constraint. Contrary to the views of some, this is not a licence for arbitrary action, nor does it mean that decisions are taken in a vacuum.”[16]

Concepts of judicial independence in 1921 were certainly much less stringent than they would later become. The Attorney General did not approve of a magistrate’s behaviour and had no hesitation in contacting him directly to order his suspension. It may have been that David Hastings should have been removed as magistrate given his close relationship with the town’s “whisky ring.” But Attorney General Raney’s ‘command and control’ approach clearly demonstrates the absence of judicial independence prevailing for magistrates at that time. Hastings was in no way free from the interference of the government in his decisions. The fact that an inquiry was called into Hastings’ jurisprudence was a modest but unmandated nod to the principle of judicial independence and one wonders if it would have been called but for Hastings’ publication of Raney’s order to Hastings that he quit his post.

Judicial Independence – Progress from 1921 to 1967

How did the concept of judicial independence evolve between the 1920s and late 1960s? Specifically, how did the relationship between the government and the judiciary change over the years; what did the concept of judicial independence mean to the day-to-day work life of provincially appointed magistrates, judges and justices of the peace?

Salaries of Judicial Officials

Until the early 1960s, judicial salaries were negotiated by the government of the day with each individual magistrate or judge. These tended to be so low that magistrates and family judges took other work to support their families. Magistrates “should be paid salaries that will enable them to live and educate their families in dignity,” wrote Commissioner James McRuer in the 1968 report of the Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights in Ontario.[17] McRuer brought to light the fact that in 1968, 37 magistrates were employed by 68 Boards of Commissioners of Police, “for which they are in some instances paid substantial salaries…. Magistrates ought not to be members of Boards of Commissioners of Police for many reasons. Not the least of these is that there ought not to be an employer-employee relationship between judicial officers and the members of the police force. Another equally sound reason is that Police Commissioners make laws. A judicial officer ought not to be engaged in the legislative process other than that which may relate to procedure.”[18] Like Magistrate Hastings of Dunnville fame juggling his judicial duties with politicking and running the local newspaper, the employment of magistrates outside the court was a recipe for generating controversy and conflict – and situations that would compromise their independence.

Similarly, virtually no justices of the peace occupied full-time, salaried positions. By the 1960s, being a justice of the peace usually was a side line to some other type of work – often a court officer or clerk. Remuneration by collection of fees was found by McRuer to be “subversive to the administration of justice. The payment of judicial officers on a piece-work basis necessarily diminished the public respect for law and order. The fee system was a real inducement to justices of the peace to curry favour with police officers in order to ‘get business.’[19]

Divorcing Politics from Judicial Compensation

Justice Kathleen McGowan served, in the 1990s, as the Chair of the Judicial Independence Committee of the Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges. She has written extensively on the topic of judicial independence. The excerpt below appeared in 2006 in an essay, “The Struggle for Judicial Independence in Canada,” included in the Journal of the Commonwealth Magistrates’ and Judges’ Association.

McGowan included the story below to illustrate why – in her words – “it is absolutely essential that we achieve a divorcing of politics from judicial compensation.”

The story was told to me by a highly respected judge who has long since passed away. This fine gentleman was appointed to the bench in the early 1960s and as was the custom in his jurisdiction his salary was paid jointly by the province and the municipality. A practice had developed whereby the Crown Attorney and the Chief of Police would meet with the judge before court every day and review the docket and decide what was going to happen with the cases. The learned judge thought that this practice was improper and announced that he would discontinue it. The Chief of Police complained to the Mayor who directed the judge to reinstitute the practice or have his salary reduced. The judge refused and in short order a bylaw was passed reducing the municipality’s portion of his salary to $1.00 a year. Fortunately for the judge, the Crown Attorney recognized that this was wrong and eventually the province took over and reinstated the judge’s full salary and the judge went on to establish a well-deserved reputation for fairness.

(Source: Kathleen McGowan, “The Struggle for Judicial Independence in Canada,” Journal of the Commonwealth Magistrates’ and Judges’ Association, Vol. 16, no 4, December 2005, p. 28.)

Magistrates and Family Judges Begin to Organize

Reflecting concern for their remuneration and working conditions, the juvenile and family judges and the magistrates formed associations – both of which were still in their infancy by the end of the 1960s, as David Vanek recalled of his early days as a Provincial Court (Criminal Division) judge.

I found the general meetings of the Association rather dull and uninspiring. Most of the discussion was devoted to securing an increase of remuneration and pensions, which were at unreasonably low levels, and improving working conditions. Unfortunately, an atmosphere of futility surrounded these discussions. These issues fell within the authority of a provincial government that disclosed no inclination to improve matters. Executive officers of the Association would address letters to the Premier, Attorney General, or other governmental authorities, in exaggeratedly deferential terms, seeking an appointment [for a meeting]. I found this embarrassing and inappropriate on the part of judicial officers…. This “cap in hand” approach to government brought little improvement. The attitude of the Provincial government reflected the low regard in which it held the magistrates and Provincial Court judges in my early years on the Bench.[20]

Vanek raised a significant point in his comments. Provincially appointed judicial officials were held in lower regard than their federally appointed counterparts, who sat on district and superior courts and enjoyed a constitutionally guaranteed judicial independence.[21]

Removal from Office

For many years, magistrates – like Hastings – and justices of the peace held their offices “at pleasure,” meaning they could be removed when it suited the government of the day. In 1952 the Magistrates Act was amended to provide that Ontario magistrates with two years’ or more experience could only be removed from office for cause – “for misbehaviour or for inability to perform his duties properly.”[22]Further, a magistrate could only be removed after an inquiry by one or more superior court judges. The junior magistrates with less than two years’ experience continued to serve as “at pleasure appointments.”

As McRuer acknowledged in his 1968 report, judicial independence although “essential” and of “incalculable importance,” should not be a cloak for preserving in office irresponsible judges or magistrates who have proved to be quite unsuitable for the tasks they have to perform.”[23] Although McRuer did not specifically consider the Hastings case, he was highly critical of the type of process to which Magistrate Hastings was subjected by Attorney General Raney because it smacked of “supervision of the judiciary” by the Attorney General.[24] It was quite possible that Hastings engaged in “misbehaviour,” but in McRuer’s concept of judicial independence, it would not be the Attorney General or the government of the day who decided that but “some body to which members of the Bar and members of the public could present grievances with respect to the conduct of members of the judiciary… a judicial council.”[25]

As for justices of the peace, they had no statutory protection whatsoever and could be removed at any point and for any reason by the government.

Did the 1952 Magistrates Act really change things?

In his 1971 seminal text on sentencing in criminal cases by magistrates and judges of the Provincial Court, author John Hogarth reviewed the appointment and tenure of these judicial officials. He suggested that the independence of magistrates may have been compromised – by Attorneys General influencing a magistrate or judge to resign. This was long after the 1952 legislation was in place requiring an inquiry before removal of a magistrate.

During the past twenty years [1951-1971], only two magistrates tendered their resignations to the Attorney-General before the removal orders were issued. There were a number of (other) instances brought to this writer’s attention where resignations had been offered in circumstances suggesting encouragement by the Attorney-General, but the details were never made public.

(John Hogarth, Sentencing as a Human Process, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971), p. 44. The two inquiries Hogarth refers to concerned Magistrates J. Bannon and George W. Gardhouse.)

Governments Exercised Their Control

Politicians made it clear about who controlled the provincial benches. In the 1920s, Attorney General Raney ruled the courts and judicial officers under his purview with an iron fist. That attitude was perpetuated. In 1963, at the Ontario Magistrates Annual Conference in Kingston, the 70 conferees were informed by Attorney General Frederick Cass that he was mandating a procedural change requiring them to hear shorter cases at the beginning of each court day to ensure witnesses did not have to sit in court for long periods of time. Cass concluded his remarks emphasizing his power over the magistrates, despite legislation in place requiring an inquiry before removal: “If I find that this is not the view of anyone occupying any court over which I have jurisdiction that person will forthwith be removed.”[26]

Further, the government – through the Attorney General – was in full control of the appointment process of judicial officials as duly noted by McRuer in the following critical comment.

There has been a tradition in Ontario that there should be a strong political influence in the selection of magistrates. This has not been peculiar to any political party…. The appointment of a magistrate on the basis of political connections cannot be justified on any ground. It is not consistent with the elementary concepts of justice that one who has attained office merely by political service should have the right to preside over the liberty of the subject… [T]he independence of the judiciary is essential in the administration of justice and is of incalculable importance…[27]

As for the justices of the peace, McRuer could not have been more clear.

We condemn without reservation and with all the emphasis at our command the appointment of justices of the peace as a political reward. Such appointments can only be termed a sort of comic opera title system that can be described in no more appropriate language than “just silly.” … We recommend that the appointments of all present justices of the peace be cancelled and a fresh start made.[28]

Inadequate Courtrooms

Accommodations for magistrates, justices of the peace and family judges affected the manner in which the courts were conducted and justice was delivered. Until 1968, Magistrates Acts made it clear that running a magistrates’ court was a “second string” activity.

Magistrates were given the right to use any courtroom or town hall, but that use “shall not interfere with the ordinary use of the courtroom” by other courts or with the use of the town hall “for the purposes for which is maintained.”[29]McRuer was particularly aware of this issue, pointing out that communities were placing these judicial officials in “entirely inadequate, poorly located and noisy” places across the province—often in police stations and even jails. ”[30] “One cannot come to any other conclusion than those responsible have no concept of the elementary rights of accused persons and witnesses who attend trials, and the rights of the public, to have justice administered with the dignity and in circumstances that convey a respect for the law.”[31]

Lack of a Centralized Administration

Magistrates, family judges and justices of the peace formed what has been termed a “fractured mosaic” of “independent operators,” each labouring alone in their own courts.[32] A centralized administrative structure for this loose collection of courts slowly began to evolve in 1922, when authority was granted to designate a “senior” magistrate, with the power to assign and direct Toronto’s three other police magistrates.[33] In 1936, the Attorney General was given the authority to designate a senior magistrate in magisterial districts throughout Ontario. Shortly before the Magistrates’ Courts and the Juvenile and Family Courts were replaced by the Provincial Courts in 1968, both the criminal bench and the juvenile and family bench were led by chiefs – Chief Magistrate A.O. Klein and Chief Judge H.T.G. Andrews. The administrative structures each oversaw were “embryonic.”[34] As McRuer detailed in his report, these Chiefs were mandated simply to “equalize the case load… and to provide for assistance in case of illness and absence,”[35] with little administrative support or structure to accomplish the task.

Judicial Independence – An Illusory Concept

In summary, the mixed bag of municipal officers, police officers and others who served as magistrates, family judges and justices of the peace before 1968 were not regarded or treated as judicially independent.

- They were not secure in their jobs – many served “at the pleasure” of the government of the day. Many worked only part time and held down other jobs to supplement their incomes – which put them into conflict with their judicial roles.

- They had very limited financial security. Magistrates negotiated their salaries individually with the government. Most justices of the peace were dependent on fees, as opposed to fixed salaries. Both arrangements were recipes for relationships too close to and dependent on police and government officials to be considered impartial.

- The often “disgraceful” and inappropriate accommodations provided to these courts provided a clear example of how judicial independence of this group of judicial officers was regularly compromised, either in fact or perception.

Judicial Independence Becomes Defined for the Provincial Courts: 1968-1989

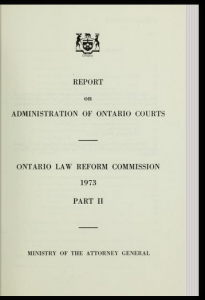

A Collection of Reports to Government-From McRuer to Mewett to Zuber to Henderson

Four important reports were delivered to government about the state of courts in Ontario – with particular focus on the provincial courts, and the independence not only of the judges and justices of the peace, but of the courts themselves. These reports, in both their timing and their recommendations, serve to frame the Provincial Courts era. Taken together, they demonstrate the progress made in defining the concept of judicial independence for judges – and the sorry lack of judicial independence for justices of the peace.

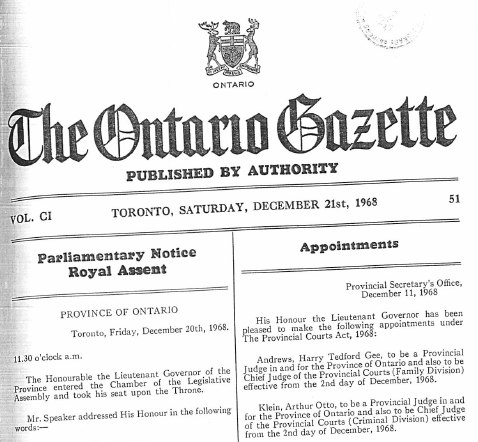

1968: Publication of the McRuer Report served to reveal significant flaws in the administration of justice in Ontario. Grave concerns about judicial independence were expressed throughout the report. Change was afoot.

By December 1968, in response to McRuer, the Provincial Courts, Family and Criminal Divisions, had been created and the magistrates became judges in these new courts.[36] This heralded a new era: “the judicialization of the magistracy” began.[37] As the judges of the Provincial Courts took their places and began defining their roles, the concept of judicial independence became increasingly – and often hotly – debated.

1981: Alan Mewett, then a law professor at University of Toronto, submitted his report to the Attorney General on the “Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario.”[38] Mewett’s findings were unambiguous.

The justice of the peace is the very person who stands between the individual and the arbitrary exercise of power by the state or its officials. It is essential that an independent person be the one to determine whether process should issue, whether a search warrant should be granted, whether and on what terms an accused should be released on bail and so on. This is a fundamental principle at the heart of the common law and in my opinion must be zealously preserved.[39]

Mewett concluded that there was “much confusion, not least in the minds of the justices of the peace themselves” about “the whole question of the independence of Justices of the Peace.”[40] Mewett was particularly concerned about the employment status of justices of the peace. They were, at the time of his report, lumped in with and considered to be employees of the government. “Anyone in a decision-making position… cannot, either expressly or impliedly, be considered as a civil servant.”[41]Further, he was highly critical of the lack of clarity around the administration of the justice of the peace bench, including directing the sittings of justices of the peace. He was equally critical of the manner in which work was assigned to justices of the peace: “the present system leads at least to the appearance of undue pressure on a justice of the peace to conform to the opinions of his superior or be assigned inconvenient or unpopular duties. Thus, the power to ‘direct’ may become a power to interfere with the judicial independence of the justice of the peace.”[42] Despite these criticisms, the independence issues facing the justice of the peace bench did not begin to be fully addressed until the 1980s.

1987: In Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry, Justice T.G. Zuber noted that judicial independence had been seriously debated in the years leading up to his investigations, and concluded that “judicial independence means many things to many people.”[43]Zuber had been appointed by Attorney General Ian Scott to study the possible reorganization and streamlining of the entire provincial court system– from justices of the peace to the Ontario Court of Appeal.[44]

Zuber raised a variety of unresolved questions about the practical workings of judicial independence.

In general terms, it could be described as the freedom of the judiciary from outside interference in discharging their essential functions. Views begin to diverge on what is the meaning of outside interference and what are the essential functions of the judiciary…. [J]udges should hold office free from the threat of dismissal by the executive or the legislature because of dissatisfaction with individual decisions. It has also been accepted that judges could not be subject to reductions in salary as a form of disapproval of or punishment for unwelcome decisions. These aspects of judicial independence are the two basic elements of security of tenure, and no one would today suggest any diminutions of the security of tenure of the judiciary. Questions begin to arise when one considers who should have the responsibility for the assignment of work to judges, the provision of financial resources for the court (in the form of buildings and personnel) and the management of the resources that are provided to the court system.[45]

1988: The Henderson Report[46]

(properly titled the Report of the Ontario Provincial Courts Committee) tackled – in practical terms – some of the questions the Zuber Report raised with regard to issues of judicial independence and focused on the remuneration of judges.

“But what, exactly, does judicial independence entail? By now there is little room for dispute about its essential contours.” The Henderson Report, 1988

The Henderson Report put flesh on the bones of the definition of judicial independence by critically reviewing and commenting upon relevant Supreme Court of Canada cases– specifically the landmark 1985 case, R. v. Valente – and the academic literature of the day.

As described by Henderson, the modern understanding of judicial independence involved two relationships which, together, are essential to true judicial independence:

- the individual independence of a judge, reflected in such matters as security of tenure, and

- the institutional independence of the court over which that judge presides, as reflected in the institutional or administrative relationships to government and other people and organizations.[47]

This “modern understanding” came almost exclusively through litigation beginning in the provincial courts across Canada. How did it happen? And when did it begin?

Individual Independence – Judges Begin to Find Their Voices

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the status of the Provincial Courts and its judges began to improve – for a number of reasons.

McRuer had identified that these courts had been seriously neglected, and that message was repeated in subsequent reports, including the Ontario Law Reform Commission’s 1973 Report on Administration of Ontario Courts.

The Provincial Courts required greater attention because of the “number of people affected by these Courts, their broad jurisdiction and the resulting voluminous caseload,” concluded the OLRC report.[48]

Simply put, the work of the Provincial Courts was becoming more important and more sophisticated. This needed to be reflected in the approaches by which their independence was guaranteed.

The OLRC report recommended as follows.

- Improved salaries and a formalized salary structure for Provincial Court judges to reflect the significance of the work of the Court.

- The appointment of only lawyers as judges of the Court, with the elimination of part-time judges “on the basis of impropriety of one holding a judicial office” while being engaged in another business.[49]

- Reduction of political influence in the appointment of judges.

- A tightening of the “loose” administrative structure of the Provincial Courts.[50]

Concurrent with recommendations such as these finding voice, the complexity of cases the Court was hearing – together with the volume of cases – was increasing. This, in turn, led to more professionalization and specialization within the Provincial Court benches. Criminal cases, for example, were being heard in increasing numbers as the Criminal Code was regularly amended during these years to allow for more offences to be heard in the Provincial Court– and more accused persons elected to be tried in the Provincial Court as opposed to the Superior Courts.[51]

That “explosion of workload” was noted in government reports concerning the Provincial Courts.[52]

The Bench was Seething

Despite recommendations dating from the 1960s that magistrates and judges of the Juvenile and Family Courts should be paid the same salary as certain federally appointed judges, Provincial Court judges had watched the salary differential between the two levels of court increase – with the Provincial Court judges stuck at the lower end of the pay scale during the 1970s.[53]

Further, there was no formal mechanism for Provincial Court judges to bring their salary concerns to the government’s attention.

“The period from 1980 to 1990 was a remarkable period of transformation in what the judiciary can and should do to advance its own interests.” Justice Paul French, Ontario Court of Justice. From 1980 to 1997, French served as legal counsel to the Provincial Judges Association (Criminal Division) and the Ontario Family Court Judges Association.

In the opinion of Justice Paul French (who served as legal counsel to the associations of criminal and family judges from 1980 to 1997[54]), the remuneration of Provincial Court judges depended on the “beneficence of the government,” a situation that dramatically compromised their judicial independence. In his memoir, Judge David Vanek concluded: “It is demeaning for judges periodically to come to the government, cap in hand, begging for money.”

French recalled, “the bench was seething…. there was a lot of chatter about the lack of judicial independence” in the late 1970s.[55]

The judges – led by their associations – decided to act.

Judge Bill Sharpe was one of the key players in the Provincial Court Judges Association (Criminal Division) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, serving as its treasurer. He was also chairman of the Salary and Pensions Committee, which Sharpe referred to with rueful humour as the “avarice and greed committee.”[56]

The Ontario Family Court Judges Association had a similar committee, led by Judge Joe James.

Judge David Vanek’s memoir recalls the circumstances of the time.

The Government of Ontario still approached the exercise of its administrative authority over the Provincial Court and provincial judges, including the salaries and pensions of the judges as matters wholly within its discretion. Bill Sharpe’s committee was encountering the usual difficulties, not only in obtaining increases to levels it regarded as reasonable but to get the government even to address the submissions of the Association. In this state of affairs, Bill convened a joint meeting of his committee with a similar committee of the Family Division of the Provincial Court.[57]

In 1979, Bill Sharpe wrote a long letter to the Premier of Ontario, Bill Davis, requesting a meeting. Sharpe’s request was granted and the judges decided they would take the opportunity to ask for the creation of a committee– comprised of one representative of the government, one of the judges and a chair acceptable to both parties – to deal with the financial matters of the judges at arm’s length from the government.

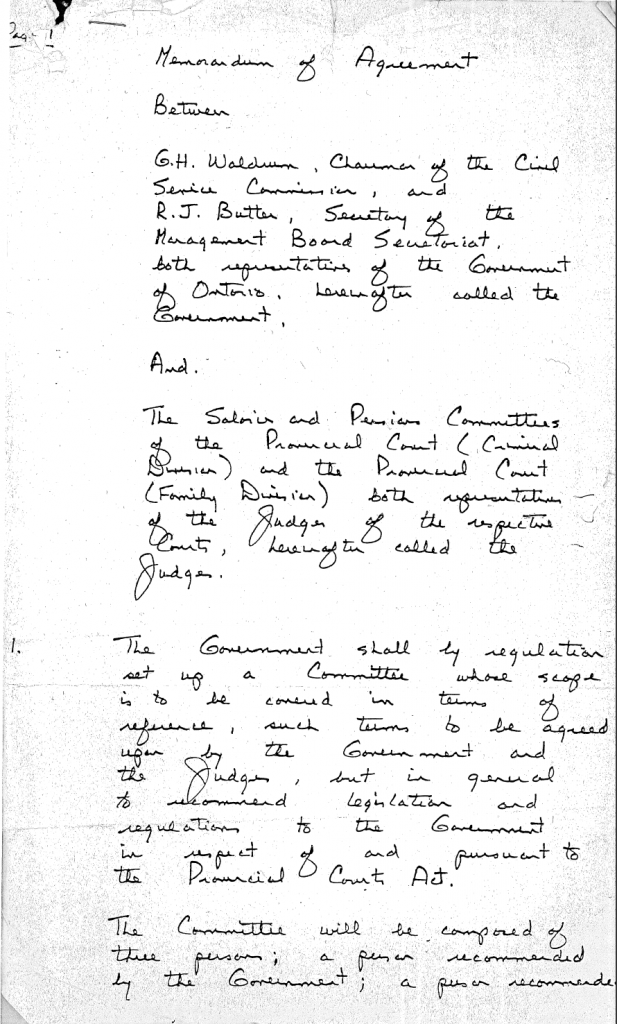

“To our delight,”[58]the proposal was accepted and the Ontario Provincial Courts Committee was created. The Memorandum of Agreement, handwritten by Judge Joe James during that meeting on December 13, 1979 was initialled by Bill Davis and Attorney General Roy McMurtry.[59]

As Paul French noted, this was the first functioning committee of its kind in North America.

Thus, the first formal step was taken toward building a structure to ensure individual independence of the judges – but it was in an embryonic state and soon to be disrupted by two realities. First, the Provincial Courts Committee simply made recommendations with no binding power, which could be ignored by the government of the day. Second, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms arrived in 1982.

The Arrival of the Charter in 1982 – Questions are Raised About Judicial Independence

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms contains a specific reference to judicial independence. Section 11(d) states that a person “charged with an offence has the right… to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal.”

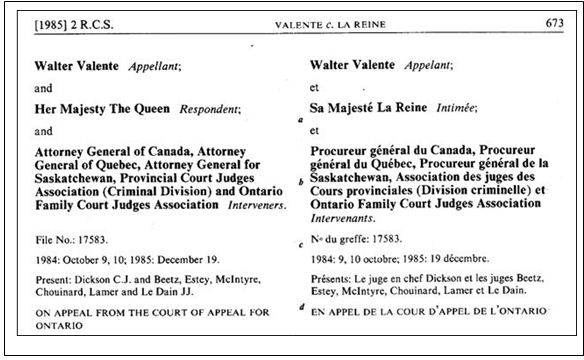

Within a year after the Charter was enacted, a challenge was made to the independence of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in the case of R. v. Valente. That case ultimately made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985 where it was decided that: “A judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) of Ontario is an independent tribunal within the meaning of s. 11(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.”[60]

“A judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) of Ontario is an independent tribunal within the meaning of s. 11(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.”

R. v. Valente, [1985] 2 S.C.R. 673

The Story of R. v. Valente

A tragic set of facts lay at the heart of R. v. Valente before it progressed from the Provincial Court to the Supreme Court – and became the “most important” judicial independence case in Canada.[61]

While driving his car at high speed along a street in Burlington at midnight on July 3, 1980, Walter Valente struck five girls on their bicycles. Three were killed and the other two were injured, one seriously. The case began in County Court before a federally appointed judge. The original charge of dangerous driving was withdrawn and a charge of careless driving was laid, a Highway Traffic Act offence that carries a potential jail sentence. Valente pleaded guilty and Judge Quinlan accepted the plea, assessing a $200 fine and suspending his driver’s licence for one year. The Crown appealed that sentence.

Because the matter was now a provincial offence, the sentencing appeal was heard in Provincial Court (Criminal Division). The case was assigned to Judge Bill Sharpe. “Valente was a crazy case,” recalled Sharpe. “At the trial, the Crown and Valente’s lawyer had made a deal for the $200 fine. The Crown then appealed the sentence handed down by the County Court judge to the Provincial Court and this is how I got the case before me in December 1982. And that’s when I said, I don’t know whether I am independent to hear this, so I won’t make a decision on it. Then the case went to the Court of Appeal.”[62]

Valente – worried that the deal for the $200 fine would be overturned by Sharpe – had instructed his lawyer, Noel Bates, to keep him out of jail. Bates turned to the Charter provision stipulating any person charged with an offence has the right to a hearing before an “independent and impartial tribunal.”[63]

Bates was aware that Provincial Court judges did not have the same constitutional guarantees of independence as judges who are higher on the judicial ladder. “So Bates argued that Provincial Court judges are not independent… because the Provincial Court judge charged with hearing Valente’s case (Sharpe) was not independent, the judge had no authority to decide the case.”[64]

Sharpe considered Bates’ argument to have merit. He disqualified himself and referred the independence question to Ontario Court of Appeal on December 16, 1982. The Court of Appeal heard the appeal with breathtaking speed because, while awaiting the decision on their independence, a number of Provincial Court judges stopped taking cases until the Court of Appeal rendered its decision. On February 15, 1983, the Court of Appeal decided that “Judge Sharpe sitting as a member of the court was independent and… he was impartial.”[65]

In other words, Valente lost. He appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada and lost again.

But there’s so much more to this story that explains why Sharpe disqualified himself in the Valente case, the involvement of the Court of Appeal and, subsequently, the Supreme Court in defining the judicial independence of the judges of provincial courts.

The Background to Valente

This was a ground-breaking case. It had its roots firmly in the fight Provincial Court judges were waging with the Ontario government, in the early 1980s, over their independence.

Sharpe, like many other judges on the Provincial Court, had for many years been irritated by the fact that federally appointed judges of the superior courts had a higher constitutional status. Sharpe, together with other provincially appointed judges, through the criminal and family judges’ associations, had been pressing the provincial government to take action to reinforce their independence. They had some success in 1979 with the creation of the Ontario Provincial Courts Committee, but judges, like Sharpe, felt there were many other issues to address. The Supreme Court did address them in Valente – the “essential contours” of judicial independence were clearly stated in that judgment.

What was challenged in Valente?

Professor Martin Friedland prepared a report for the Canadian Judicial Council in 1995 on the subject of judicial independence and accountability, in which he reviewed the history of the development of judicial independence.

Within a year after the Charter was enacted, a challenge was made to the independence of the Ontario Provincial Court bench [in the Valente case]. There were 18 grounds alleged for holding that the judge was not independent. Many of these involved differences from federally appointed s. 96 judges. Salaries, for example, were determined by the executive branch and not by the legislature as with s. 96 judges. And salaries and pensions were not, as with s. 96 judges, a charge on the consolidated revenue fund. Further, removal of provincial court judges did not, as with s. 96 judges, require a vote by the legislature.

(Martin Friedland, A Place Apart: Judicial Independence and Accountability in Canada,(Ottawa: Canadian Judicial Council, 1995), p. 8.)

The Valente Decision

The Supreme Court of Canada identified the three essential elements of judicial independence.

- Judges must have “security of tenure” – they cannot be fired because the government disagrees with their decisions and they cannot be removed for making an error in law, but only for behaviour inappropriate for a judge (such as bias or other types of misconduct).

- Judges must have “financial security” – their right to a salary must be legislated so that the government cannot manipulate judges by raising or lowering their salaries or threatening to do so.

- Judges must have “administrative or institutional independence” – decisions regarding the assignment of courtrooms, cases and judges, all of which could potentially affect judicial decision-making, had to be made by judges and not by a public servant in the employ of a government ministry.[66]

The “first two elements of independence – security of tenure and financial security – relate largely to individual judges. The third element, administrative independence, speaks more to the court as an institution.”[67]

The Two Aspects of Judicial Independence: Individual and Institutional

The Supreme Court was clear – judicial independence has two aspects involving:

- The individual independence of each judge, and

- Institutional or administrative independence of the court.

“It is generally agreed that judicial independence involves both individual and institutional relationships: the individual independence of a judge, as reflected in such matters as security of tenure, and the institutional independence of the court or tribunal over which he or she presides, as reflected in its institutional or administrative relationships to the executive and legislative branches of government…. The relationship between these two aspects of judicial independence is that an individual judge may enjoy the essential conditions of judicial independence but if the court or tribunal over which he or she presides is not independent of the other branches of government, in what is essential to its function, he or she cannot be said to be an independent tribunal.”

(R. v. Valente, 23 C.C.C. (3d) 193, para. 20)

A Tumultuous Time: The View of Roy McMurtry, Attorney General (1975-1985)

As this excerpt from Roy McMurtry’s memoir demonstrates, this was a time of heated and acrimonious debate about the definition of judicial independence, the relationship between the Ontario government and Provincial Court judges, and the judges’ motivation for raising the issue.

After my appointment as attorney general, I became aware of some tension between my ministry and the provincial court judges over the issue of salaries.

Some judges alleged that there was at least a perceived conflict of interest in a system where an independent judiciary relied on the prosecuting government for salaries and court administration. They argued that, as provincially appointed judges, they were disqualified from performing their functions because of the degree of control exercised by the provincial attorney general and that this fact raised a reasonable apprehension that judges could be biased in favour of the prosecution. After the entrenchment of the Charter of Rights in the Constitution in April 1982, several provincially appointed judges even threatened to stop hearing criminal cases because they regarded themselves as not being independent of the attorney general as the chief prosecutor. In my view, the protest was chiefly a strategy to obtain higher salaries through some form of independent arbitration.

(Source: Roy McMurtry, Memoirs and Reflections.)

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back – The Impact of Valente on Financial Security

Although Valente was a strong statement from the Supreme Court that arrangements must be in place to ensure independence, at both the individual and institutional levels, the decision “wasn’t the panacea a lot of people had hoped it would be,” recalled French.[68]

In 1981, the Ontario Provincial Courts Committee had recommended that, by April 1985, the salaries of Provincial Court judges should be increased to the same level as that of federally appointed District Court judges. But raises at that level were not forthcoming.

In January 1985, Chief Judge Ted Andrews, Provincial Court (Family Division) told The Globe and Mail: “The Ontario government has failed to implement the recommendations of an independent committee set up specifically to advise the government on judges’ salaries and other benefits and conditions…. Professional pride is about the only thing that is holding judges to their commitments right now. After a while they’re going to have that diminished a bit.”[69]

The general consensus of the judges – the Provincial Courts Committee had been ineffective.

After the June 1985 provincial election, a new government came on the scene: the Conservatives were out; the Liberals attained power.

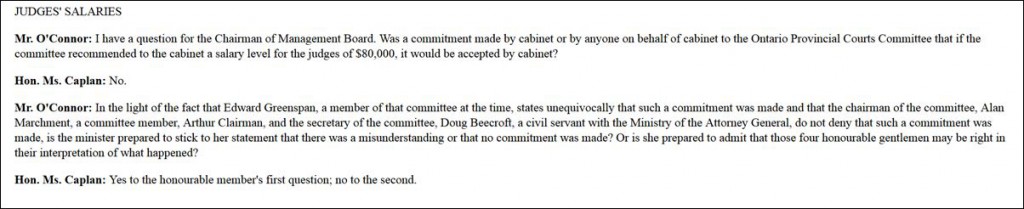

The tension between the government and the judges continued to mount. In October 25, 1985, it boiled over when Elinor Caplan, chairman of the Management Board of Cabinet, announced in the legislature that the Ontario government had “decided not to accept the 1981 recommendation of the Ontario Provincial Courts Committee to establish parity between the salaries of Provincial Court judges and those of federally-appointed District Court judges.”[70]

On November 19, 1985, the judges’ representative on the committee, criminal defence lawyer Edward Greenspan, resigned. In his resignation letter, he wrote that he had been misled about the salary issue by the government. French, quoted in the Toronto Star on December 2, 1985, stated the judges’ position clearly: “That committee was established so an independent body would decide on salaries. This government has ignored their advice… and in so doing it has tampered with that independence.”

The battle between the judges and the government continued over salaries – and was extensively detailed in newspaper articles. Headlines announced: Judges cry foul over talks on salaries[71]and Judges and Scott at odds over wages.[72]

Attorney General Ian Scott’s Recollections of the Remuneration Issue

Ian Scott, who served as Attorney General between 1985 and 1990, recalled the handling of the salary issues and the disagreements between the judge and the government in his memoir, To Make A Difference.

Provincial court judges were the ones most citizens were likely to brush up against. They handled most criminal charges and many matters arising out of marital breakdown…

I was forcefully reminded that provincial court judges deserved the same respect, and the same salary, as federally appointed judges. Ted Andrews, the chief judge of the provincial courts, surprised me by raising the issue at a public ceremony. My response was as follows:

‘I also want to emphasize that I am conscious of the concerns of the members of the Provincial Court Bench about remuneration. I very much regret that the representatives of the Provincial Judges have not seen fit to reappoint their nominee to the statutorily established Provincial Courts Committee. I have met with representatives from the Provincial Judges on a number of occasions and will continue to do so in order to ascertain whether a more suitable mechanism for examining issues of compensation cannot be devised. I must make it plain, however, that it is the position of the government that no mechanism can be established which removes or reduces the authority of the government of the day to control or determine the expenditure of tax dollars to be allocated for judicial remuneration.’

Supreme Court of Ontario judges disagreed with Chief Judge Andrews’ view on levels of remuneration. Some of the provincial court magistrates were not lawyers: this proposal would have the effect of elevating them to the same level as other judges, who were all lawyers, an outcome not popular with the Supreme Court of Ontario judges.

(Ian Scott, To Make a Difference, (Toronto: Stoddart Publishing Co. Limited, 2001), p. 177)

The furor culminated in April 24, 1987, when “all the Provincial Court

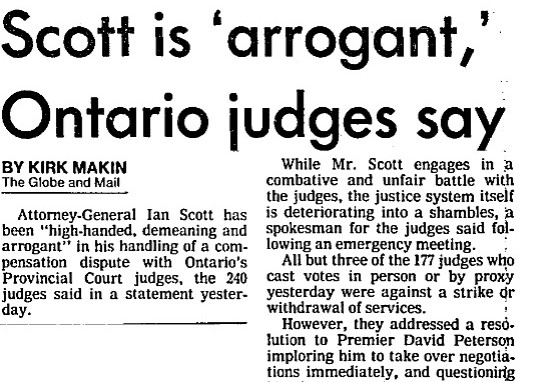

judges in Ontario met to consider their options collectively. At a press conference in Toronto’s Royal York Hotel held after that meeting, their legal counsel, Paul French, announced that the judges had passed a resolution requesting the personal intervention of the Premier.”[73] The difference between the annual salaries of Provincial Court judges and federally appointed District Court judges was set to grow to $50,000. The press conference served to make the Provincial Court judges’ position clear. Attorney General Scott was “high-handed, demeaning and arrogant” in his handling of the compensation dispute. While all but three of the 177 judges who cast votes were against a strike or withdrawal of services[74]…“everything is on the table,” Paul French declared.[75]

Three months later, the Provincial Courts Committee was reactivated, with lawyer Gordon Henderson as its chair. This restructured committee reported on September 27, 1988. The report critically reviewed the Valente decision (and reminded the government of its obligations) and provided a detailed review of the financial and social restrictions placed on judges that were necessary to maintain judicial independence and the obligations judicial independence imposed on the government.

The Henderson Report concluded that Provincial Court judges’ salaries should not be tied to those paid to District Court judges. Among other reasons, the report pointed out that the two groups of judges are paid by two different levels of government, with the result that judicial remuneration scales that might be appropriate for one level of government may be inappropriate for another.[76] However, the report advocated a significant increase in the salaries of Provincial Court judges to be “sufficiently generous to offset the financial and social restrictions Provincial Court judges must endure as a cost of insuring their independence…We have paid particular attention to the reported earnings of partners who have fifteen to twenty years’ experience practicing in small and medium-sized firms. Our recommendation establishes a salary structure that we believe will be attractive to better than average lawyers in Ontario who have ten or more years’ private practice experience and who are willing to exchange some income for the security of tenure and the honour of a judicial appointment.”[77]

Answering the Media’s Questions About Judicial Compensation

On September 20, 1996, Judge Kathleen McGowan, was interviewed on CBC Radio in her role as Chair of the Judicial Independence Committee for the Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges.

The CBC interviewer asked McGowan the following question: “How do we separate your (the judges’) concerns for judicial independence form judges’ concerns, legitimate as they may be, about what they’re paid?”

Here is McGowan’s response:

Our concern is the process by which we deal with government, so basically what judges are saying is that after a lengthy history of going cap in had to various Attorneys General to talk about salaries, we have felt that there could possibly be a very strong perception in the mind of the public that judges are dependent upon the Attorney General for their salaries. In fact, what we’re requesting is that there be a separate independent process so that judges can deal with government in a manner which allows them to be independent of various ministers and yet allows the public to see that the manner in which judges are remunerated from the public purse is fair and reasonable.

(Source: Metro Morning, CBC/CBL Radio (Toronto), September 20, 1996.)

The Costs of Judicial Independence

The Henderson Report included a section entitled “The Costs to the Judge of Maintaining Judicial Independence,” in which the obligations of the judge are detailed, together with the resultant restrictions on the judge’s life. It was clear much had changed since the days of Hastings, Raney and the Dunnville Whisky Ring.

At the heart of the notion of judicial independence is the conviction that the individual judges must have complete liberty to hear and decide the cases that come before them. Here, as elsewhere, such liberty has both a negative and an affirmative aspect. Negatively, it means that nothing may constrain or distract the judge from entertaining the full range of available options for disposition of a particular case: the judge’s bearings are to come exclusively from the law itself. Affirmatively, it means that the decision, irreducibly, is the judge’s alone. Each of these aspects of their office sets judges apart from people in other callings.

Although it is traditional to be concerned about governmental interference with the judicial function, government is not the only source of danger to judges’ independence: many others have something to gain or lose from the outcomes of particular disputes. Any significant connection a judge may have with such people or organizations threatens to predispose him or her toward certain solutions to legal problems involving them. Such potential predispositions are no more tolerable with respect to private parties than with respect to government. As Shimon Shetreet has said in Judges on Trial:

A judge must be free from political or other pressures. This means that a judge must first be immune from such systems of distorting justice as direct pressure, bribery or approaches by the litigant, a friend or counsel: he must also be removed from any sophisticated entanglements, be they political, personal or financial, which might seem to influence him in the exercise of his judicial functions, let alone entanglements that might actually influence him.

The consequence is that judges must, upon taking office, dissolve any business or financial connections they may have had before their appointment (and make no new ones while on the bench), terminate their political affiliations and withdraw (or distance themselves) from personal relationships they may have developed with former professional colleagues. In isolated cases, judges may, and do, disqualify themselves from presiding at matters involving individuals or organizations with whom or with which they have or have had some connection. The clear understanding is that they will arrange their affairs in such a way as to maximize their capacity to hear without conflict the cases within their court’s jurisdiction. For those who preside in the smaller centres, where few other judges may be nearby to substitute in cases of possible conflict, the need for circumspection is acute.

Essential though they clearly are, such sacrifices and restrictions distort the lives of Provincial Court judges in several important ways. First, they keep to a minimum the occasions when judges may exercise their constitutionally guaranteed rights of association and free expression; whatever a judge’s private convictions, he or she must subordinate them to the cultivated impartiality of the judicial role. Second, they isolate the judge from many ordinary forms of social interaction within his or her community. Such isolation breeds loneliness, especially in those accustomed to the collegial atmosphere in which most lawyers practice. Finally, …the judge’s unique position inhibits his or her ability to follow many business opportunities. Judges do not have the same flexibility of investment that they had as members of the practicing bar…. The judge stands alone and on public display. He or she must face individually any criticism directed against his or her decisions or conduct as a judge.

Such criticism – no matter how personal or how unfounded – must be borne in silence: the canons of independence prohibit judges from making any public response. A judge’s personal feelings of grievance must not be allowed to give anyone occasion to doubt the disciplined detachment of judicial deliberation.[78]

Moving Beyond Valente

The Henderson Report made it clear that its conception of judicial independence for provincially appointed judges in Ontario went beyond the minimum standard the Supreme Court of Canada set out in R. v. Valente. The report pointed out that, in Valente, the issue was not the articulation of an ideal standard of the independence of the Provincial Court judge.

The task instead (in Valente) was to ascertain the absolute minimum conditions sufficient to make a tribunal independent enough to try offence proceedings… Repeatedly throughout the judgments, the Supreme Court observed that existing occupational arrangements for Provincial Court judges ‘fall short of the ideal’… and that higher standards of judicial independence…‘may well be preferable…’

We accept the invitation to endorse a higher standard. Judicial independence, in Canada, has constitutional status. Governments should always be prepared to hold themselves to higher standards of constitutional behaviour than those the courts are prepared to enforce against them.

(Henderson Report, pp. 50-51.)

“Henderson was a godsend,” stated French. “Henderson and the others on his committee (Mary Eberts and William Hamilton) travelled the province and solicited views along the way. The government implemented almost all of the recommendations in the report. The key message of the report was to ‘treat professionals as professionals.’ The report made the judges feel good and respected. And, the government had an entirely new attitude toward the judges.”[79]

Despite this new attitude, it did take time for government to act on the Henderson Report. The year 1989 ended with Provincial Court judges agitating for the Henderson Report to be acted upon – and their salaries to be raised in accordance with the recommendations contained in the report. “The judges are of the view that the time is now,” said Judge Allan Sheffield, president of the Ontario Family Court Judges Association. “The level of morale is lower than I have ever seen it on the bench.”[80] All was set to change in 1990 with the introduction of new legislation governing the judges of the Provincial Courts, which was foreseen, and the election of a new NDP government, which was not.

The Fight for Judicial Independence – Was it Only About Judicial Self-Interest?

Some have equated the Provincial Court judges’ fights for judicial independence with judicial self-interest. After all, many of the battles did concern their salaries and demands for more money. Attorney General Roy McMurtry was certainly alive to that view: “the [judges’] protest was chiefly a strategy to obtain higher salaries.”

For the judges, there is no doubt that increased remuneration and formalized structures for negotiating salaries at a distance from the government were critical to defining “financial security.” An April 25, 1987 article in The Globe and Mail indicates that salary issues were top of mind for Provincial Court judges, but other independence issues – such as independence from the police – were also of concern.

“In their statement yesterday, the judges said a Government (of Ontario) proposal to peg their salaries to those of assistant deputy-ministers means they are seen as civil servants. ‘So the judges feel that the very independence of the judiciary is now at stake,’ it said.

The judges said their salary levels are too low to attract high-quality judges. ‘In sum, the judges have exhausted every reasonable means at their disposal to bring about a solution to the problem, but nothing has happened,’ the statement said.

(Mr. French, counsel representing the judges), told reporters that the judges deeply resent recent statements by Mr. Scott implying the dispute is limited to money. Moreover, they are ‘enraged’ that Government spokesmen consistently tell the media they work only three to five hours a day.

A great deal of routine judicial duties and research goes on in each judge’s chambers, the statement said. However, judges cannot speak out to refute these arguments…. ‘The fact is that judges are, in a very real sense, imprisoned by their office.’

Strike action or withdrawals of service are unlikely in the future, Mr. French said. He referred vaguely to ‘administrative’ actions the judges could eventually take if the Government does not reach an agreement with them.

Taking the opportunity to complain about the justice system, the judges spoke of dangerous courthouse conditions and towering case-loads. They said these conditions ‘have led to what can only be described as a “crisis” in our judicial system.’

Justice in Ontario is rendered through a second-class system, they said. Among their examples:

- A courthouse was recently condemned as unsafe for public use.

- Makeshift courtrooms have been set up in rented parish and legion halls, in community centres and in taverns. “Some are located in police offices, in which the unavoidable contact between the judge and police leave many citizens wondering about the impartiality of the whole system,” they said.

- Courthouse security for witnesses and the public is “at a minimum” and dangerous individuals are shunted through public areas.

- There are so few Crown Attorneys that cases are often interrupted when new attorneys have to take over. Many defence lawyers have to be retained as part-time (Crown counsel), and end up negotiating plea bargains with fellow defence counsel.

- The caseload is so great that it is impossible to complete cases within a reasonable time.

(Kirk Makin, “Scott is ‘arrogant,’ Ontario judges say,” The Globe and Mail, April 25, 1987.)

“Institutional” or “Administrative” Independence: Changes in the Approach in the 1980s

In the 1980s, the individual independence of the judges – security of tenure and financial security – drew most of the attention of the judges and the media, but there were also discussions about how the administration of the courts and the process for judicial appointments had an impact on judicial independence.

The Zuber Report Summarizes the Issues Concerning Court Administration

Zuber made it clear in his report that contours of administrative independence were still a “grey zone” in 1987: “Questions begin to arise when one considers who should have responsibility for the assignment of work to judges, the provision of financial resources for the courts (in the form of buildings and personnel) and the management of the resources that are provided to the court system.”[81]

The question of who should control the administration of the court was relatively new at the time Zuber delivered his report.

Historically, the Court had very little to do with its own administration. Scant attention was paid to the scheduling or management of cases – “because they did not appear to require it.” The judge’s role was simply to adjudicate the disputes that appeared on a court docket. Prior to the 1970s and 1980s, “trial court dockets were relatively short, as were the trials themselves, and there was no particular pressure or need to create more effective ways to deal with cases.”[82] That all changed by the mid-1970s with an “explosion of workload” in the Provincial Court, especially in criminal cases.

This workload issue was detailed in a 1976 report prepared by Ontario’s Ministry of the Attorney General, which recommended that the Court have control over certain of their own processes.

It is only in recent years, with the explosion of workload, that it has been necessary to exert authority over the court system by the application of modern management techniques through case-flow management… It is essential to recognize that effective case-flow management can only be achieved if those responsible for that management are responsible for, and have control over, the allocation of all resources necessary to implement case-flow control.[83]

This recommendation was met with some public hostility in 1976. The proposal was seen as a transfer of administration of major public resources into the hands unelected, unaccountable members of the judicial branch of government.[84]

In his report, Zuber stuck to a conservative approach to court administration. Yes, the judiciary should have “final say on matters of assignment of judges, standards for judges’ workloads, assignment of individual cases and the arrangement of a sitting schedule.” But, Zuber also counselled: “The administration of all other aspects of the court system would be left in the hands of the Ministry of the Attorney General with the provincial government having final authority on certain matters. To ensure co-ordination of the efforts of the judicial and administrative sides and the constant interchange of information, a permanent courts management committee should be set up.”[85]

The Appointment Process is Revolutionized – JAAC Comes into Being

Concerned by the role political patronage played in the appointment of judges, Attorney General Ian Scott set out to change the way judges were appointed to the Provincial Courts. The Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee (“JAAC”) was established in December 1988; to address this concern. Originally envisioned as a three-year project, it replaced the Ontario Judicial Council and began advising the government on prospective judicial appointees. The Ontario Judicial Council was composed of the Chief Justices and Chief Judges of all Ontario courts, representatives of the bar and two non-lawyers. Its primary function was to serve as a disciplinary body for provincial judges, but the Courts of Justice Act also gave it a role in the appointment process.[86]

The relationship between the judicial appointment process and independence requires a short explanation. By the late 1980s, concern was growing that appointments to the Provincial Courts were a reward for political services. The fear was that this perception “may precipitate the belief among both the public and the legal profession that… judges, having attained their position as a result of the government’s favour, are therefore obligated to that government, in a manner which might undermine the independence of the judiciary. The effect on public confidence in the legal system could be corrosive.”[87]

Ian Scott described the JAAC model in his memoir. “I instituted a new appointments system that has a different focus. Instead of inquiring about party affiliation, I looked for two things: I wanted judges to be appointed on merit, and I wanted them to reflect more accurately the diverse Canadian population. In the new system, anyone who wished to be appointed to the bench had to make a formal application, and had to be recommended by the local bar association. This put a kind of quality-control check on the beginning of the process. Next, hopeful judges had to apply to an appointments committee, headed by Peter Russell, whose expertise in judicial and constitutional subjects was universally acknowledged. The people on this committee were selected to represent different communities and viewpoints. The committee itself had a built-in affirmative-action edge; it was eager to have the courts represent the diversity of modern Canadian society. They recommended a short list of candidates to me, and I made my selection from that list. This took old-style politics out of the process. The new appointments system was an important breakthrough. It helped to recruit many women judges, and it helped to make the bench more professional and competent.”[88]

The Judicial Independence of Justices of the Peace is Challenged – the Currie Case

As with the judges, the judicial independence of the justices of the peace has been challenged in the courts.

In the early 1980s, while Valente was wending its way upwards through the courts, but before a decision was handed down by the Supreme Court of Canada, a similar case challenging the judicial independence of Ontario’s justices of the peace, began its life in the Niagara region.

Mr. Charles Currie was facing a charge under the Niagara Escarpment Planning and Development Act[89]. Justice of the Peace Murray Allen – a salaried justice of the peace, as opposed to a fee-for-service justice – was presiding in the trial of Mr. Currie, who happened to be represented by the same lawyer that represented Mr. Valente – Noel Bates. Mr. Bates did what he had done in Valente and challenged the jurisdiction of all justices of the peace in the province.

Once again, Bated relied on s. 11(d) of the Charter, arguing that justices of the peace were without jurisdiction because they were not independent and impartial when trying the prosecution of provincial offences. Bates began with an application to the Ontario’s High Court of Justice (a predecessor of the Superior Court of Ontario), basing his argument on a number of issues which included the following:

- Justices of the peace lacked security of tenure because they held their offices at the pleasure of the government.

- They were not able to perform any judicial duties unless directed to do so by a Provincial Court judge – and, therefore, dependent on a higher level of the judiciary.

- The classification system of justices of the peace resulted in salary variations amongst them.

- Justices of the peace could be paid through “fee-for-service” arrangements which could make them dependent on the goodwill of the police.

Bates relied heavily on the Mewett Report – in particular Mewett’s comments that the appointments and removal process for justices of the peace was “chaotic” and “clearly violates every principle of judicial independence.”[90]

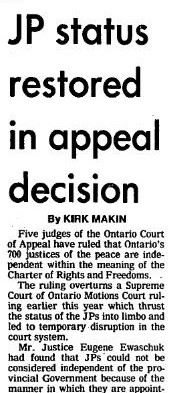

At Ontario’s High Court, Justice Ewaschuk agreed with Bates’ arguments and decided that Justice of the Peace Allen and all other justices of the peace were not independent. He prohibited any justice of the peace from hearing the prosecution against Mr. Currie. Justice Ewaschuk delivered his decision on June 19, 1984.

Ewaschuk’s decision threw the justice of the peace system into a virtual state of collapse. The immediate effect was that many justices of the peace adjourned hearings and generally refused to process matters until the issue was settled – in other words, they were waiting for an appeal of Ewaschuk’s decision to the Ontario Court of Appeal.

The story gets more complicated.

Ewaschuk’s decision made it clear that he had not given consideration to a brand new piece of legislation governing Ontario’s justices of the peace – the Justices of the Peace Amendment Act, 1984, which had been proclaimed effective May 1, 1984. This legislation was not in force when Mr. Currie was originally charged, thus the case had to be determined under the older Act. The new legislation had changed many of the factors Bates had cited in his arguments in the Currie case. For example, justices of the peace could no longer be removed “at pleasure” of the government. They could only be removed for cause on the basis of a complaint investigated by the Justices of the Peace Review Council.[91] The fee-for-service arrangements disappeared – all justices of the peace, under the 1984 amendments, were paid on an hourly basis or became salaried.[92]

Subsequently, on Friday, June 22, 1984, in an unrelated case dealing with a separate matter that arose after May 1, Justice of the Peace N.R. Burgess ruled that, despite the changes made by the Justices of the Peace Amendment Act, 1984, he lacked the judicial independence to preside over a trial.[93]

When Currie made its way to the Ontario Court of Appeal, that Court considered the law both before and after the May 1 enactment of the Justices of the Peace Amendment Act, 1984. The December 5, 1984 Court of Appeal decision adopted a practical approach to the issue, reviewed the statute law and practice relating to justices of the peace, and decided that they were sufficiently independent.

“The statute law has been continually evolving until it has reached its present state. Many of the recommendations made in the McRuer Royal Commission Report and the Law Reform Commission of Ontario Report of 1973 have been accepted and implemented, as well as some of those made by Professor Mewett. While the statute law has been evolving, the equally important traditions have remained constant. When these considerations are interrelated in the mind of the reasonable, informed and fair-minded observer, such observer would conclude that the sitting justices of the peace, in reality and perception, have the necessary independence to discharge their judicial duties.”[94]

As with the judges, the justices of the peace entered the 1990s with their judicial independence reinforced.

The Pace Picks Up – A “Renaissance for the Court”: 1990-1999

Scott’s “Big Picture” Plan for Court Transformation

It was clear by the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s that Attorney General Ian Scott had a big picture in his mind for the transformation of the courts in Ontario.

Some of these changes were implemented in the 1990s and nearly all of them had major impacts on the judicial independence, particularly the administrative independence, of the new Ontario Court (Provincial Division).

Increased Administrative Responsibility for the Operation of the Court

September 1, 1990 was a landmark day for the Court. The Provincial Courts (Criminal and Family Division) were replaced by the Ontario Court (Provincial Division). Sidney B. Linden was appointed Chief Judge of the integrated Court.

This change was seen as “Phase I” of Ian Scott’s vision for court reform. Phase II was to see the Superior and Provincial Courts integrated into a single “unified” trial court. Phase II never came to be. Five days after the proclamation of the Courts of Justice Act that September, a provincial election was held and the government changed hands. The NDP did not share the former Liberal government’s agenda for court reform – and Attorney General Scott was replaced by Attorney General Howard Hampton.

Linden recalled those days. He came into a Court that had seen the nature, volume and scope of its work increase over the previous decade. Recent amendments to the Criminal Code had widened the jurisdiction of the Provincial Court.[95] Cases had become much more complex, and Provincial Court judges were, by 1990, routinely required to make decisions on intricate issues of law and procedure, in both criminal and family law. In many criminal cases where the accused had a choice of which court to select, the Provincial Court had become the court of choice, preferred over the superior courts.

Linden believed that the new Court could not be a true partner in the management of the judicial function without judicial leadership that could help the Court to adapt to these very different conditions. He and Scott had shared the idea of a cooperative management system but Linden was not sure the NDP agreed with that approach. Linden decided to take action, even though the Attorney General who had appointed him was gone and a new government was in place.

Linden embarked on a radical makeover of the administrative structure of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), which ultimately resulted in a significant increase in the administrative – or institutional – independence of the Court.[96]

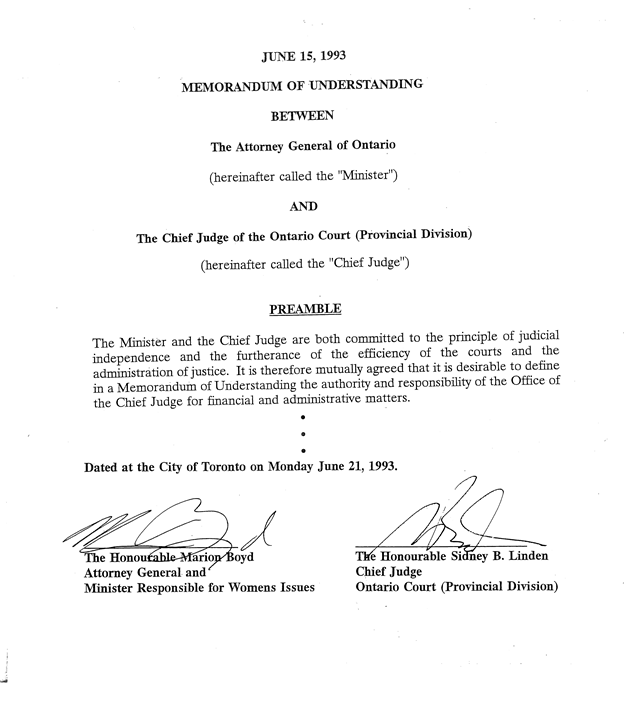

Administrative Independence – The Introduction of the Memorandum of Understanding Between the Attorney General and the Chief Judge

The story of how the increased administrative independence came to be is best told by Linden himself.

For decades prior to 1990, the judiciary, especially the Provincial Court judiciary, had very little administrative responsibility for the operation of the courts, or for the administrative support of judges. Despite the best efforts of former Chief Judges, there was little or no involvement by our judges in such areas as: financial management; operational decisions; the implementation of judicial support programs; the use of statistical and management information for assessing caseloads or judicial resource needs; or the day-to-day administrative needs of the judges.

The Provincial Court was managed as if it was a small branch or division with the Attorney General’s Ministry. Officials within the Ministry provided the Provincial Division with necessary support services including financial monitoring, and the scant statistical information that existed was, at best, only intermittently shared with the Chief Judge’s office.