R.v. Nelles: “No Evidence to Send Nurse to Trial”

Dowson v. Canada (Royal Canadian Mounted Police): Judge accused of sticking to police like Krazy Glue

R. v. Askov

The Viking Houses Cases: “Municipalities challenge orders of Family Court judges”

Re L.D.K. (An Infant): 12-year-old girl opposes blood transfusion

R. v. Nelles: “No Evidence to Send Nurse to Trial”[1]

“Undoubtedly, my single most important case was the Nelles case.”

Judge David Vanek[2]

Chief Justice Sidney B. Linden in Preface to David Vanek’s Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge, April 21, 1999.

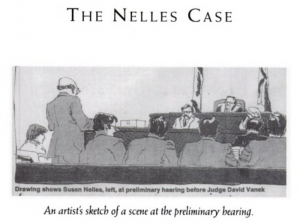

When Judge David Vanek entered the courtroom at Old City Hall in Toronto on January 4, 1982, his task was to preside over a preliminary inquiry on murder charges. He had no idea that this would ultimately entail 45 days of hearings, involve over 100 witnesses and many exhibits[3], and require him to author a lengthy decision that would captivate the public and dominate the headlines.

The defendant was Susan Nelles, a young nurse in the cardiac ward of Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. She was accused of acts both abhorrent and totally at odds with the values of her profession: murdering four infants by deliberately administering overdoses of the drug digoxin.

In serious criminal matters, trials are preceded by a preliminary inquiry held by a Provincial Court judge. The purpose is to determine if there is sufficient evidence for the case to go to trial before a federally appointed judge, sitting alone or with a jury. The threshold is not high. As long as the Provincial Court judge finds that there is “any evidence” on which a properly instructed jury could find guilt, the case will be sent to trial.

Because the threshold is low, most cases do proceed to trial and defence lawyers often decide not to call witnesses at the preliminary inquiry stage. They will, however, cross-examine prosecution witnesses in order to learn more about the case against their clients.

Judge Vanek quickly realized that the Nelles case was not going to be a typical preliminary hearing. The defence team, led by lawyer Austin Cooper, vigorously argued that there was insufficient evidence on which to send Nelles to trial.

Evidence

Although the charges against Susan Nelles related to four specific deaths, “similar fact evidence” indicated that there were “twenty-four babies who had died on the cardiac ward in the same time frame and in suspiciously similar circumstances.”[4] There was, however, also evidence that Nelles was not on duty during the day when one of the four babies had died, and that she was on vacation when one of the other suspicious deaths occurred.

Judge Vanek refused to infer guilt on the basis of Nelles not having been fully forthcoming in her statement to the police. He expressed the opinion that the statement “merely reflects the exercise by Susan Nelles of two of the most elementary and fundamental civil rights of a citizen when charged by police officers with an offence: the right to speak to a lawyer and the right to remain silent.”[5]

Vanek worked feverishly to prepare his written reasons for judgment which took three weeks to complete. Fortunately, Chief Judge Fred Hayes agreed to free him from his regular schedule of court duties.

The judge gave his ruling in a packed College Park courtroom on May 21, 1982. Tight security was called for, with police officers controlling entry due to intense public and media interest in the case, pent up by the length of the proceedings and the order Judge Vanek made prohibiting publication of the evidence. While media had attended the proceedings, publication of details was banned until judgment was issued.

The Decision

Judge Vanek held that the test for committal to trial had not been met. Accordingly, he directed that Susan Nelles be discharged on all four counts of murder.

This decision was based in part on Vanek’s findings that the evidence was entirely circumstantial and no evidence was presented to establish motive.[6] He also concluded that, regarding three of the four children, the evidence was at least equally consistent with innocence as guilt. And for the fourth child, there simply was no evidence that could go before a jury.[7]

Regrets

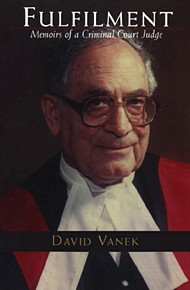

Ten years after retiring in 1989, David Vanek recalled the experiences of his 21 years on the bench in the book Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge, and expressed two regrets arising from the Nelles case.

The first regret was having uttered the comment, as an aside, when reading his judgment, “This is a whodunit!” This was interpreted by the media to mean Vanek believed the four babies had been murdered, which was not a finding he had made or was required to make.[8]

His second regret was having concluded that “[t]here is evidence that points in a different direction.”[9] This was an oblique reference to the fact that another nurse “had as much opportunity as Nelles and was equally or even more likely to be the guilty party.”[10] Newspaper reports indicate that this other nurse never escaped the shadow of suspicion that she may have murdered the babies.

What Came Next?

Vanek’s ruling marked an end to the Provincial Court’s involvement in the so-called “Sick Kids murders”. However, other proceedings were initiated – by government and by Susan Nelles – that kept the matter under public and legal scrutiny.

The Ontario government appointed a Royal Commission of Inquiry headed by Justice Samuel Grange of the Ontario Court of Appeal. The purpose was to examine how the infants on the cardiac ward died and review the circumstances surrounding the investigation and prosecution of the criminal charges. Grange’s report was supportive of decisions Vanek had made in the preliminary inquiry and suggested Nelles should receive compensation.[11]

Susan Nelles’ civil lawsuit for malicious prosecution was finally heard by the Supreme Court of Canada on the question of whether cabinet ministers and prosecutors can be shielded from prosecution. In 1989, the Supreme Court ruled that Nelles could continue her action against the Attorney General for malicious prosecution.[12] She had already settled with the police.

Mystery Solved?

Many fine minds thought that the baby deaths were the result of deliberate overdoses of digoxin.

Cooper: “Between January 11 and March 22, 1981, four infants who were patients in the cardiac ward at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto died as a result of the deliberate administration of overdoses of a heart drug called Digoxin.”[13]

Grange: “There is of course always a chance of fatal error in drug administration, but in my view, if any substantial number of these patients died from an overdose of digoxin, the suggestion that those overdoses were all accidentally administered is preposterous.”[14]

Judge Vanek wrote, “In the end, how twenty-four babies, who were not expected to die, came to their death at Toronto’s renowned Hospital for Sick Children remains a mystery.”[15] That mystery still lingers over 30 years later. Some doctors, lawyers, scientists and journalists are convinced that the babies were not murdered, that the testing of digoxin levels was highly unreliable, that the syringes used at the time were dangerous to frail infants, and that the nurses were the victims of overzealous pathologists and hasty police work.

Conclusion

As Vanek expressed in his memoir, “It would have been expedient, and not unusual, simply to hold there was sufficient evidence for committal, offer a few words to this effect, and leave the issue to a judge or judge and jury for disposition at a trial.”[16] But he did not take the easy way out in this complicated and high-profile case where the evidence was circumstantial and, in his mind, not legally probative of guilt.

What conclusion can be drawn, then, about the kind of judge he was? Vanek said he could accept lawyer Harold Levy’s assessment published in the Toronto Star with reference to the Nelles case: “And she drew a crusty, tough-minded, fiercely independent provincial court judge, who was determined to call the shots as he saw them instead of passing the buck to the judge and jury at trial”[17]

- Regina v. Nelles 15 CCC (3d) 97, par. 67 ↩

- Vanek, David. Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge (Toronto: The Osgoode Society and Dundurn Press, 1999), p. 285 ↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 293 ↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 289↩

- Regina v. Nelles 15 CCC (3d) 97, par. 67 ↩

- Regina v. Nelles, par. 96, items 1 and 2 ↩

- Regina v. Nelles, par. 96 and 97↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 298↩

- Regina v. Nelles, par. 96, item 9 ↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 299↩

- Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry Into Certain Deaths at the Hospital for Sick Children and Related Matters, The Honourable Mr. Justice Samuel G. M. Grange, Supreme Court of Ontario, Commissioner, 1984.↩

- Nelles v. Ontario, [1989] 2 S.C.R. 170↩

- Cooper, Austin. “Susan Nelles: the Defence of Innocence,” in Greenspan, Edward L., ed., Counsel for the Defence: The Bernard Cohn Memorial Lectures in Criminal Law (Toronto: Irwin Law, 2005)↩

- Grange, Report of the Royal Commission, p. 40↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 299↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 293↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 308↩

Dowson v. Canada (Royal Canadian Mounted Police): Judge accused of sticking to police like Krazy Glue[1]

Ross Dowson was a political journalist and senior official with the League for Socialist Action. He claimed that two officers of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) had conspired to discredit him through false and injurious statements.

The Provincial Court

(Civil Division)

During the 1980s, the Provincial Court had a Civil Division in which full-time judges heard Small Claims Court cases.

In 1982 he sued the police force and the officers for damages and the case was heard in the Provincial Court (Civil Division).

Dowson’s case became notorious, not for the substance of the decision, but for what happened when one of Dowson’s lawyers publicly criticized the judge.

The Lawyers and the Judge

The following men were key players in what transpired to make the case notable.

Judge Marvin Zuker

The presiding judge, Marvin Zuker dismissed the case against the RCMP, primarily because the lawsuit had been filed after the six-month limitation period for persons exercising a public duty.

Charles Roach

One of Dowson’s lawyers at the trial, Charles Roach had been a plaintiff before Judge Zuker in a previous Small Claims Court case involving a different police force.

Harry Kopyto

Dowson’s other lawyer was Harry Kopyto. After Judge Zuker issued his decision, Kopyto was interviewed for an article published in The Globe and Mail on December 18, 1985, in which he was quoted as follows.

This decision is a mockery of justice. It stinks to high hell. It says it is okay to break the law and you are immune so long as someone above you said to do it.

Mr. Dowson and I have lost faith in the judicial system to render justice.

We’re wondering what is the point of appealing and continuing this charade of the courts in this country which are warped in favour of protecting the police. The courts and the RCMP are sticking so close together you’d think they were put together with Krazy Glue.

This statement was widely reported in the media and Zuker became known as the “Krazy Glue Judge”.

A Charge of Contempt of Court

It is rare for lawyers to be so vocal in their criticism of judges and the courts. Kopyto was charged and convicted of contempt of court on the basis of his comments. The trial judge found Kopyto’s statements to be a “vitriolic unmitigated attack” on Zuker and “a blatant attack on all judges of all courts”.[2]

Kopyto was later acquitted by the Court of Appeal on the basis of his right to freedom of speech. As poetically put by Justice Peter Cory of that Court, “[t]he courts are not fragile flowers that will wither in the hot heat of controversy.”[3]

Postscript: Zuker and Kopyto meet again

Twenty-five years after the Dowson case, Harry Kopyto – then a disbarred lawyer – sought to appear as an agent in a family matter. The matter came before Zuker, who had become a family court judge of the Ontario Court of Justice.

Justice Zuker did not find Kopyto to be qualified as an agent. Kopyto then lodged a complaint against Zuker with the Ontario Judicial Council. The complaint involved alterations to a transcript which Zuker admitted, with regret, to having done.

A Previous Case Against the Police

Roach v. Adamson et al.

The Dowson lawsuit was not the first case involving Charles Roach and heard by Judge Zuker. While Roach appeared as Dowson’s lawyer in 1985 , he was the plaintiff in Roach v. Adamson et al., heard in 1979 shortly before the Provincial Court took on a Small Claims Court role.

According to Zuker, “Charles Roach, a well-known civil rights lawyer, was stopped by the police near his office because they were looking for somebody Black. I wrote a lengthy decision, basically saying you can’t stop someone because of the colour of their skin. You have to have some more basis. There was no basis for stopping him, other than the fact they were looking for somebody Black and he happened to be Black”.

Zuker’s judgment included a monetary award of $512 for Roach. As a consequence of the amount being over $500, the police were entitled to appeal. The Divisional Court reversed the decision, although a further appeal to the Ontario Court of Appeal upheld Zuker’s original decision in favour of Roach.

This case was regarded as somewhat of an anomaly in cases heard at the Ontario Court of Appeal. As Justice Zuker observed, “It may have been the only case that I can recall, offhand, of my ten years as a Small Claims Court that hit the Court of Appeal.”

The Dowson case resulted in a perception that Zuker was biased in favour of the police, while in the Roach case he had decided in favour of the plaintiff against the police.

Sources: M. Zuker, Oral History, 2008-2009, Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History (used with permission); archival copies of decisions courtesy of M. Zuker: Small Claims Court (Feb. 21, 1980), Divisional Court Order (July 9, 1981), Court of Appeal Order (Feb. 19, 1982).

Conclusion

The Provincial Court heard Small Claims Court disputes for only a decade beginning in 1980. In 1990 this function was transferred to what later became known as the Superior Court of Justice. However, as the Dowson and Roach police cases show, the issues raised by small claims cases – and the repercussions they may generate – can be noteworthy indeed.

- Ross Dowson v. Stanley V.L. Chisholm, Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Ronald Yaworski [1985] O.J. No. 1762; 16 Admin. L.R. 169; 34 A.C.W.S. (2d) 146. ↩

- As quoted by Cory J.A. in R. v. Kopyto, (Ont. C.A.) 62 O.R. (2d) 449; [1987] O.J. No. 1052. ↩

- R. v. Kopyto, (Ont. C.A.) 62 O.R. (2d) 449; [1987] O.J. No. 1052. ↩

R. v. Askov[1]

Few decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada have had so profound an impact on the practical day-to-day work of the court as R. v. Askov, released October 18, 1990. Askov concerned the right of a person charged with an offence to be tried within a reasonable time, as guaranteed by section 11(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The right to be tried within a reasonable time is of such fundamental importance that the Supreme Court decided that the only possible remedy for a violation of that right is a stay of proceedings. This effectively puts an end to the legal action and the accused person walks free. Thus, if the state cannot bring an accused person to trial within a reasonable time, it forfeits the right to try that person at all. Since a stay is such a drastic remedy, the question of what constitutes “reasonable time” is important and frequently a challenge to answer. Often, courts will look at what occurs in other cases and in other jurisdictions to assist in defining what is reasonable. That is precisely what occurred in Askov.

In November 1983, Elijah Askov and three co-accused were charged with conspiracy to commit extortion against Peter Belmont. Belmont operated an agency in Montreal that supplied exotic dancers to licenced clubs in Ontario. In the past, Toronto clubs had been among his clients. More recently, however, one of Askov’s co-accused, Edward Melo, had established himself as a local supplier of exotic dancers in the Toronto area. When Belmont attempted to re-establish his Toronto operation, a 50% commission payment was demanded. When he refused, Melo and Askov threatened him. They were arrested shortly thereafter, along with two associates. The preliminary inquiry and trial were to be heard in Brampton, Peel District, with the inquiry starting in early July 1984 but not completed until that September. A trial was then set for the first available date in October 1985. An overwhelming number of other cases scheduled for that time resulted, however, in the trial being put over to September 1986 – almost two years after the preliminary hearing. When the trial finally commenced, Askov moved for a stay of proceedings on the basis that his right to be tried within a reasonable time had been breached. The trial judge granted the stay. That decision was overturned by the Court of Appeal, but subsequently upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1990. This promptly turned the entire justice system on its head.

Sidney Linden, Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (it was then called the Ontario Court (Provincial Division))[2] at the time of the Askov decision, recalled that “everybody in the system knew Askov was coming, everybody knew there was going to be an explosion down the road. It was taking longer and longer for cases to come to trial. People were coming into the Provincial Division and getting dates two years hence.”[3] While the explosion may have been anticipated, no one could have predicted how far the aftershocks would travel or for how long they would continue to be felt.

Trial Within a Reasonable Time

In its reasons for reinstating the stay ordered by the trial judge, the Supreme Court made a number of comments about the then-prevailing state of affairs in Brampton. That venue was – and remains – a very busy court, in part because of urban growth and population density, but also due to its proximity to Pearson International Airport, where drug-related offences frequently occur. At the time, the Brampton Court was also suffering from a lack of court space and judges. As the Supreme Court noted, this area had “long been notorious for the inordinate length of time required to obtain a trial date.”[4] The situation in Brampton was “a deplorable state” and something was “terribly wrong.”[5]

The Supreme Court cited a study completed by Professor Carl Baar in 1987, which had concluded that Brampton was undoubtedly one of the worst districts in Canada in terms of delay.

If Canadian courts were required to set cases for trial within six months, they could almost universally do so. No Provincial Court in Canada is normally setting cases for trial or preliminary hearing more than six months after first appearance. Of the five provinces with county courts, only one location in one province routinely sets criminal cases for trial more than six months after committal: Ontario’s Peel County Court in Brampton. That court has set trial dates a full ten months ahead, perhaps the longest delay in Canada.[6]

In fact, according to Professor Baar’s study, the progress of cases in the Brampton courthouse was substantially slower than even the slowest United States jurisdictions. The delay in Askov was longer than 90% of all cases heard in Brampton, making it “one of the worst from the point of view of delay in the worst district not only in Canada, but so far as the studies indicate, anywhere north of the Rio Grande.”

The situation actually deteriorated further after those data had been gathered. In 1987 – after the Baar study was concluded – Justice Zuber released his Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry. He had been mandated to investigate the “jurisdiction, structure, organization, sittings, case scheduling and workload of all of the courts of Ontario,” and report his findings. Justice Zuber also discovered that “Brampton had the greatest backlog in the province with a waiting period of one year regardless of the anticipated length of trial.”[7] He noted that the delay in reaching trial was exacerbated by the absence of a system to ensure an early second trial date was prioritized where – as in this case – the first trial date was missed.[8]

Although the government of Ontario had instituted a Delay Reduction Initiative in six regions – including Brampton – the initiative “stressed more efficient use of the region’s facilities rather than the provision of additional resources” and was described by the Supreme Court as “obviously insufficient.” In the Supreme Court’s view, the “only conclusion that can be drawn from an analysis of the material filed is that the problem of systemic delay in Peel has not and cannot be resolved simply by introducing a more efficient caseflow management system. More resources must be supplied to this district perhaps by way of additional Crown Attorneys and courtrooms.”[9] The Supreme Court added that this conclusion could come as no surprise since the problem had existed “for many years, back at least as far as 1981.”[10] On this point, the Supreme Court repeated the words of the trial judge in Askov, District Court Judge Bolan.

I am satisfied that the reason for the delay was caused by the insufficient institutional resources in the Judicial District of Peel. Even if more judges had been available for the jury sittings of October 15, 1985, there would have been no courtrooms in which to hold the trials. It is obvious that this jurisdiction lacks sufficient resources to meet the demands and administer the criminal justice system with minimal delay. This has caused a systematic delay in the administration of justice. It was this way when I came here in 1981 and it continues to be this way today [September 1986]. … Those responsible for the proper administration of justice have known about this systematic delay for at least five years; yet nothing has been done about it.[11]

Describing the state of affairs as unacceptable and intolerable, the Supreme Court suggested several possible interim solutions to assist in addressing the problem. Courtroom space could be located in nearby government buildings, or in portable structures such as those often used in schools. In appropriate cases, a change of venue might be ordered so that the trial could be heard more quickly in a less busy court. Whatever the solution, it was clear something had to be done urgently. Otherwise, the Court would increasingly face the “unfortunate and regrettable”[12]situation of having cases end in a stay of proceedings rather than concluding with a trial decision based on the merits.

The Supreme Court noted that the question of “how long is too long” to bring a case to trial would always be difficult to answer and would depend in part on the particular facts of each case. For that reason, it held no fixed “reasonable time” from arrest to trial would be applicable in every region. Nevertheless, the determination of what was reasonable in any region should not be undertaken in isolation, but by comparing the local delay to the best comparable jurisdiction in the country.

The Globe and Mail, March 20, 1991

The Globe and Mail, March 18, 1991

The number of cases appearing before the Criminal Division in all locations was increasing markedly, as a result of both demographic and legal changes. In addition to rapid population growth, primarily in urban areas, the Court also had to grapple with the impact of the Charter and increased “hybridization” of criminal offences, which expanded the criminal jurisdiction of the Court. Not only were more charges tried before the Court, but the proceedings were often far more complex and time-consuming. The advent of the Charter precipitated an increase in pre-trial motions – for example, seeking the exclusion of evidence alleged to have been obtained in breach of the accused’s Charter rights – which further complicated trial scheduling.

Hybrid Offences and Provincial Court

Criminal offences fall into three categories. At the most serious end of the spectrum we find “indictable” offences, such as murder. The least serious are “summary conviction” offences, e.g., causing a disturbance. In the vast middle ground reside “hybrid” offences – which the prosecutor can choose to treat as either summary or indictable depending on the facts of the offence and the circumstances of the offender. For example, the offence of assault is broad enough to encompass everything from a simple shove to a beating. It may be committed by someone who has never been in trouble with the law before or by someone with a lengthy criminal record. Designating the offence of assault as hybrid gives the prosecutor discretion to proceed in a manner that is appropriate to each individual case.

What significance does this have for the work of the Ontario Court of Justice? All summary conviction matters fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Provincial Court. Similarly, all hybrid offences which the prosecutor elects to treat as summary conviction offences also fall within the Court’s purview. When Parliament “hybridized” a number of offences in the 1960s to 1980s – that is, made offences that were previously only indictable into hybrid offences – the effect was to dramatically increase the number of cases treated as summary conviction matters and thus heard before the Provincial Court.

The prosecutor is not the only party who has choices to make in a criminal proceeding. If an accused is charged with an indictable offence or with a hybrid offence that the prosecutor has chosen or elected to treat as indictable, the accused generally gets to elect whether to have his or her trial in the Superior Court (in which case a preliminary inquiry will normally be held in the Provincial Court) or to waive the right to a preliminary inquiry and proceed directly to trial in the Provincial Court. Only for the most serious offences, such as murder and treason, is the accused required to be tried in the Superior Court.

As the criminal jurisdiction of the Provincial Court expanded through increased hybridization and as the Court developed greater expertise in criminal law matters, an increasing number of accused persons chose to have their trials in this Court. As of 2015, more than 95% of all criminal offences in this province are tried in the Ontario Court of Justice.

When the comparative analysis set out by the Supreme Court was applied in other cases proceeding in the Provincial Court, the length of time it had taken to bring many of those cases to trial was found to violate the right of the accused to be tried within a reasonable time. The Askov decision therefore resulted in thousands of charges being stayed across the province, thus placing Ontario’s justice system in “a critical position.”[13]

Between October 1990 and March 1991, a total of 205,995 criminal charges were dealt with by Ontario’s justice system; 32,254 charges – approximately 15% – were stayed, dismissed, or withdrawn as a result of Askov. Immediately following the release of the Askov decision, 74% of all criminal charges in the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) – more than 150,000 charges in all – were at risk of being stayed. By March 1991, through the efforts of the entire justice system, only 35% of charges remained at risk.[14]

Although the immediate response to Askov was swift and, in many respects, quite effective, the number of charges that remained at risk – despite the assiduous efforts of all justice system participants – underscored the need for more permanent systemic change.

Responding to Askov

Michael Code – now Justice Code of the Ontario Superior Court – was counsel to Mr. Askov in his appeal to the Supreme Court. Code recalls that when he took on the Askov appeal he knew it would be a significant case, though no one could have anticipated quite how significant.

Everyone knew we were in a crisis situation with the growing backlogs. In a cluster of jurisdictions, the situation had become intolerable. It was clear something would have to give. When the Attorney General filed his reply factum, he confirmed how dire things were. Brian Trafford – now Justice Trafford of the Superior Court – appeared on behalf of the Attorney General and was pressed quite hard by the Supreme Court justices. At one point, Justice Bertha Wilson asked whether, if the Askov case were to be sent back for hearing in the Provincial Court, it would be given priority. Trafford quite fairly said he couldn’t give that assurance. As of that moment, I was fairly certain that the Supreme Court would direct a stay of proceedings.[15]

When the Supreme Court issued its judgment in October 1990, Code was pursuing a Master of Laws degree at the University of Toronto. His thesis – subsequently published as Trial Within a Reasonable Time – involved a comparative study of two counties on either side of the American/Canadian border and the approach each took to the administration of criminal justice. When the Attorney General sought assistance to help solve the crisis that resulted from the Askov decision, Code was an obvious candidate to provide informed advice. In addition to having considerable knowledge and experience, Code also came from the defence bar – outside the Attorney General’s office – and brought a wealth of fresh ideas along with a willingness to push for meaningful institutional change in his new position as Assistant Deputy Attorney General-Criminal Law.

Changing the Culture of Criminal Proceedings

As Assistant Deputy Attorney General-Criminal Law, Code focused on three specific measures to relieve pressure on the courts.

- Lobby the federal government to reclassify additional offences as hybrid rather than strictly indictable. This provided Crown Attorneys much-needed flexibility to determine whether the facts of a given offence justified the full indictable procedure, including the right to a preliminary hearing as well as a jury trial, or whether they could be appropriately dealt with through a summary conviction proceeding.

- Make diversion programs available for minor offences and encourage absolute discharges for first offences. This helped ensure that judicial and other resources were appropriately focused on more serious offences.

- Encourage the early resolution of criminal charges. The Attorney General commissioned a report from G. Arthur Martin, a former Court of Appeal judge widely recognized as one of the foremost Canadian criminal law experts, which recommended early charge screening, early disclosure, and early resolution discussions to reduce the number of cases proceeding to trial.

For early resolution to be successful, both Crown prosecutors and defence lawyers had to begin to prepare their cases far earlier, and judges had to assume a more active case management role. As Code recalls, these were significant changes to everyday practices within the criminal justice system. Prior to Askov, the culture was one of last-minute pleas and last-minute withdrawals. That meant that most cases would set trial dates and stay in the system, and continue to demand resources, right up until the eve, or sometimes the very day, of trial. Changes in practice were widely adopted that provided for serious criminal cases to undergo a judicial pre-trial in advance of setting a trial date. Facilitating pre-trial conferences on such a broad scale was a new responsibility for the judges of the Provincial Court, and Code found that some members of the judiciary were initially reluctant to depart from their traditional role of only presiding over trials. Code and newly-appointed Chief Judge Sidney Linden travelled across the province meeting with judges to break down resistance to judicial pre-trials. Over time, and through communication and collaboration, judicial pre-trials became a familiar aspect of the work of the Provincial Court – and continue to play a vital role in encouraging early resolution of criminal cases.

When Michael Code became Assistant Deputy Attorney General in 1991, the early resolution rate (the percentage of cases resolved prior to setting a trial date) was below 50% in Ontario. By the time he left the Attorney General’s office in 1996, the early resolution rate had almost reached a targeted 70%.[16] This significantly reduced the pressure on trial courts.

Changing the Composition of the Court

The Askov decision presented an opportunity to transform the makeup of the Court as well as its practices. An NDP majority government, led by Premier Bob Rae, had been elected on September 6, 1990 – just weeks before the Supreme Court released its judgment in Askov. Howard Hampton, who had been re-elected as MPP for Kenora-Rainy River, was on vacation in Calgary when he received a call from Rae, asking if he wanted to be Attorney General. Hampton was reluctant. He remembers alerting Rae to the impending upheaval. “The Attorney General’s office is a hell of a mess and it’s about to get bigger. The Askov case has gone to the Supreme Court of Canada, and I think it’s going to blow sky high. It will take the first four of five years of any government to deal with it.”[17] Despite his misgivings, Hampton was appointed Attorney General on October 1, 1990. Hampton recalls the joke at the time was that Rae himself wanted to be Attorney General but decided against it once Hampton reviewed the potential implications of Askov with him.

The impact of Askov was even more far-reaching than initially anticipated, in large part because of the government’s response. Hampton tells the story of how Askov changed the face of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division).

John Snobelen, a cabinet minister in Mike Harris’ government, once said, “What we need is a good crisis to allow us to make some change.” Asko was a crisis – and we were determined to take the opportunity it presented to make progressive changes to the courts. We knew there were increasing numbers of women, Aboriginal, and racialized lawyers who were qualified to be appointed to the bench, but they simply weren’t applying. So with the help of the Law Society of Upper Canada, we reached out.

The response was far beyond anything we could have anticipated. We received an unbelievable number of responses from women who had practised for 15 or 20 years, well recognized as leaders in their area of practice. They said, “It was like somebody had just dropped a bomb.” The Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee was incredibly receptive. Peter Russell, the chair of the committee, said to me, “We are flabbergasted by the résumés of some of these people, not just their practice, but their work in professional education, communities, lecturing at law schools, pro bono work.”

Askov came in about two weeks after I was sworn in, in October 1990. The first round of proposed appointments came up towards the end of November. I made it known that we were going to appoint equal numbers of women and men. I was very public about it, and it caused a bit of a commotion. People said, “The best qualified lawyers should be appointed.” I replied, “Then in the first round they may all be women!”

Lawyers also came forward from racialized communities and First Nations. The First Nations appointments got lots of media attention. It was almost unprecedented at the time for members of First Nations to be appointed judges.

Some of the reactions to the push to appoint more women to the bench were unanticipated – and quite humorous. Hampton recounts:

I used to have breakfast with Chief Justice Charles Dubin of the Ontario Court of Appeal, and one morning I found him looking very somber. He said, “Mr. Attorney, I am not happy.” He dug in his pocket and pulled out a letter. He said, “My wife got this letter and is seriously thinking of applying to the bench. And I think that one judge in the family is enough!” I knew his wife, Anne Levine, was an excellent and very well-regarded lawyer, so I said, “I hope you will inform your wife that she is welcome to apply, notwithstanding the fact that she is married to you.” He said, “You would not believe the reaction from my wife when she got this letter from you. She said that she can do anything I can do, and better!” Then he laughed.

Changing the Administration of the Court

For Sidney Linden, who had been appointed Chief Judge of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) on September 1, 1990 – less than two months before Askov was released – the task of responding to the challenges it posed was almost overwhelming. As Linden noted in a speech to the Criminal Lawyers’ Association in 1996, “all of us in this room knew for years that this crisis was looming, but it couldn’t have come at a worse time for a new government, a new Attorney General, and a new Chief Judge.”[18] Faced with a heavily overburdened judiciary, a serious lack of administrative infrastructure, and a shifting political landscape, Linden briefly thought about resigning. Instead, he got to work.

New judicial appointments – 35 in total – were certainly very welcome, but like former Attorney General Ian Scott, Linden knew that an effective response to Askov would require more than simply increasing the complement of judges. The administration of the Court would also have to be fundamentally reformed – with a formal structure introduced. In fact, the funds the NDP government used to pay for the new appointments had been set aside by Scott to improve court infrastructure, technology, and administration. Although the funds had been reallocated towards new appointments, Linden was determined not to lose sight of Scott’s goals. Linden read everything he could get his hands on regarding case-flow management and court administration, and attended conferences across Canada and in the United States, talking to experts on judicial administration. In some respects, he realized, Ontario lagged behind other jurisdictions – a situation he resolved to correct.[19]

Some administrative reform measures were already afoot. On September 1, 1990 – five days before the provincial election that brought the new NDP government to power and approximately seven weeks before the Askov decision was released – the Courts of Justice Act [20] was proclaimed. The Courts of Justice Act created a new regional structure for the Provincial Court, and enabled the appointment of Regional Senior Judges (RSJs) responsible for the day-to-day operational management of each region. Of the 35 new judicial appointments, eight were judges appointed to sit in place of colleagues who were reassigned as RSJs, freeing them to focus on court administration matters. [21]

Two Acting Associate Chief Judges, (ACJs) Mary Hogan and Grant Campbell, were also named. Two positions of Associate Chief Justice were subsequently statutorily formalized, and, in 1996, Marietta Roberts and Brian Lennox were appointed as ACJs. The ACJs, the RSJs, and representatives of the family and criminal judges’ associations together composed the newly-formed Chief Judge’s Executive Committee (CJEC). Linden, who had extensive administrative and managerial experience prior to being appointed to the bench, established CJEC as part of a formal administrative structure for the Court. CJEC assumed responsibility for setting the policy direction of the Court on administrative matters and for making decisions regarding province-wide issues, such as the backlog problem that Askov had brought to the fore.[22]

The Office of the Chief Judge was reorganized and assumed new administrative responsibilities, including providing support to both judges and justices of the peace in areas such as program and financial management, and the implementation of statistical information systems. For the first time, the Court began to systematically gather data on its operations – data essential to determining how best to make use of available resources in order to minimize delay.[23]

The Legacy of Askov

Askov was unquestionably a crisis for the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), but it also presented a vital opportunity to re-examine and reform its practices, composition, and administration. The impact of the changes made in the wake of Askov continues to be felt today. Pre-trial conferences are now an established part of the work of the judiciary. The judges themselves are more representative of the diverse communities they serve. And the Court is far better organized, and able both to assess its performance and manage its resources effectively using data collected from across the province. While these changes may have come about eventually, there is no doubt that Askov dramatically increased the speed and drive with which they were implemented.

- [1990] 2 S.C.R. 1199. ↩

- On September 1, 1990, the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and the Provincial Court (Family Division) became the new Ontario Court (Provincial Division) and Sidney B. Linden was appointed Chief Judge of the new Court. In 1999, the Court became the Ontario Court of Justice.↩

- Transcript of S. Linden’s oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1998 (used with permission). ↩

- p. 1234. ↩

- p. 1236. ↩

- p. 1235. ↩

- Zuber, T. G. Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry. (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1987), p. 54. ↩

- Zuber Report, pp. 190-93. ↩

- p. 1237. ↩

- p. 1237. ↩

- p. 1237. ↩

- p. 1240. ↩

- Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Official Reports of Debates (Hansard), 35 (26 March 1991) “Court System” (Hon. Howard Hampton). ↩

- Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Official Reports of Debates (Hansard), 35 (26 March 1991) “Court System” (Hon. Howard Hampton). ↩

- Interview of M. Code for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Interview of M. Code for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Interview of H. Hampton for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Notes for Luncheon Address to: Criminal Lawyers’ Association Spring Education Program, April 20, 1996: “Where We Are, Where We’re Going!” at p. 3. ↩

- Transcript of S. Linden’s oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1998 (used with permission). ↩

- R.S.O. 1990, c. C43. ↩

- “Where We Are, Where We’re Going!” at pp. 3, 6; Transcript of S. Linden’s oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1998 (used with permission). ↩

- “Where We Are, Where We’re Going!” at p. 6. ↩

- “Where We Are, Where We’re Going!” at p. 5; Transcript of S. Linden’s oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1998 (used with permission). ↩

The Viking Houses Cases: “Municipalities challenge orders of Family Court judges”

The Regional Municipality of Peel was not pleased to have paid more than $1.2 million over six years to the Viking Houses group homes.[1] And it was definitely not pleased with the judges of the Provincial Court (Family Division) who had ordered such payments to support the care of “juvenile delinquents.” Eventually, Peel and the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto became fed up. They challenged the judges’ authority and, in two separate cases, the Supreme Court of Canada supported the municipal position.

The Juvenile Delinquent’s Act

When judges of the Provincial Court (Family Division) declared a child to be a juvenile delinquent, they had to decide on a course of action. The available options were listed in section 20(1) of the Juvenile Delinquents Act, a federal statute that was replaced in the 1980s. During the 1970s, family judges used this section to place children in a rapidly expanding network of group homes. They also used their powers under section 20(2) to order municipalities to pay the cost of care.

A Trying Time for the Peel Children’s Aid Society

The 1970s are remembered as a difficult time for the Peel Children’s Aid Society. A history of the agency notes that it had “some major and highly publicized disagreements with a private group-home operator and with the judiciary.”

The history refers to a 1975 report, Children in Trouble, which concluded that “a very serious state of affairs exists between the Court and the Children’s Aid Society.”

The history specifically mentions that Family Court Judge Warren Durham “was rarely receptive to CAS advice on the placement of juvenile delinquents. He often ruled that they be housed in Viking Homes at regional expense, despite arguments by the Society that they could be cared for much more effectively and less expensively in other settings.”

(Source: A Constant Friend: A History of the Peel Children’s Aid Society 1912-2012.)

“There was a strong desire to avoid placing children in training schools but the province directly funded only a relatively small number of family-like settings in the community,” recalled former family judge George Thomson. “And Children’s Aid Society resources were always stretched thin.”

Many group homes benefited from this approach. Among these was “Viking Houses” (sometimes referred to as “Viking Homes”), a rural program based near Chatham and led by two charismatic individuals, David Aird and George Bullied.

Many children were placed with Viking Houses because of decisions made by Judge Warren Durham. “He was a passionate judge who spoke out when he felt the youth before him were not being well served”, said former family judge Jim Karswick. “He became convinced that Viking Homes could meet the needs of many of the most difficult juvenile delinquents before him.” Judge Durham and the Peel Children’s Aid Society strongly disagreed on this point.

Not surprisingly, municipalities were alarmed by the financial burden being imposed on them as a result of orders made by Judge Durham and other judges. Two separate cases involving municipal challenges of Viking Houses placements were pursued all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. Both involved Peel and one involved Metropolitan Toronto as well.

The First Supreme Court of Canada Decision[2]

In the first case, the Supreme Court ruled that Provincial Court (Family Division) judges did not have the jurisdiction to order placements to Viking Houses because these group homes did not clearly fit within any of the options specified in section 20(1) of the Juvenile Delinquents Act.

Exasperation at Calculating Payments

Justice Blair of the Court of Appeal referred to the “exasperation of the Family Court Judges at having to deal in great detail with financial matters.” He noted that “[t]he essential task of the Family Court Judges is to consider the welfare of children and not to adjudicate upon complicated questions of cost accounting.”

He quoted Provincial Court Judge Durham as having stated, in a juvenile delinquency case, “I will say clearly that I am not going to hear the matter of whether $43 [per day] is appropriate or not. That’s already been determined, and I don’t intend to go through that again.”

(Source: Attorney General (Ontario) and Viking Houses v. Peel, 1977 CanLII 47 (ON CA); 16 OR (2d) 765; 36 CCC (2d) 337.)

One of the options under the Act was to commit a child to the care or custody of a probation officer or “any other suitable person.” Lawyers for Viking Houses advanced the argument, among others, that their client should be considered such a “suitable person”. However the three courts that heard the case – the Supreme Court of Ontario, the Ontario Court of Appeal, and the Supreme Court of Canada – did not agree. Viking Houses was a business enterprise operated by a corporation. While corporations are legal “persons” for many purposes, they could not be considered to be persons in the context of caring for a child.

As a result, the committal orders of several Provincial Court family judges – including judges Durham, Langdon, Weisman and Felstiner – were set aside. This did not mean that the placements to Viking Houses were bad for the children. It just meant that ordering such placements was not permissible under the legislation. In the Supreme Court of Ontario decision, Justice Holland made the following comment:

It is apparent from the reasons for judgment of Judge Felstiner and implied from those of the other Judges whose orders are in question here, that these Judges, who are undoubtedly experienced in the handling of juvenile delinquents, are of the view that placing juvenile delinquents in this type of setting is beneficial…. I accept the views of the Judges of the Family Court that they have found that this type of setting has proved to be beneficial in many cases.[3]

This Supreme Court decision did not spell the end of group homes in Ontario. To survive, however, they would need to maintain good relationships with children’s aid societies who could place children there.

The Second Decision of the Supreme Court of Canada[4]

With knowledge of the initial results of the first case, Judge Durham ordered a girl to be placed under the care and custody of Thomas MacKenzie, a supervisor working for Viking Houses. He also ordered Peel to pay MacKenzie, who would of course, turn the funds over to Viking Houses. The higher courts agreed that as an individual, MacKenzie qualified as a “suitable person.” So this time the placement was not set aside.

However, there remained the issue of whether section 20(2) of the Juvenile Delinquents Act – which permitted Provincial Court judges to order municipalities to pay the costs of care – was constitutionally valid. In the first case, since the committal orders were held to be invalid, the Supreme Court of Canada did not find it necessary to make a constitutional ruling about the payment provision. The Supreme Court of Ontario and the Court of Appeal, however, had ruled that section 20(2) was “a necessary part of the effective operation of the entire statute, and was validly enacted by Parliament under its powers in relation to criminal law.”[5]

In the second case before the Supreme Court of Canada, section 20(2) was ruled to be invalid. Justice Martland, speaking for the panel of judges, determined there was no authority for the federal Parliament to “impose a financial burden upon an institution, such as a municipality, which is the creature of the Provincial Legislature, and whose powers, including the power to raise and spend money, are defined solely by provincial legislation.”

Thus, the power of Provincial Court (Family Division) judges to order municipalities to fund the cost of care for juvenile delinquents had come to an end.

- Regional Municipality of Peel v. Viking Houses, 1982 CanLII 2053 (ON SC); 38 OR (2d) 78. This was a case in which Peel brought an action to recover moneys paid to Viking Houses. ↩

- Supreme Court of Ontario: Re Regional Municipality of Peel et al. and Viking Houses, 1977 CanLII 1411 (ON SC); 16 OR (2d) 632; 36 CCC (2d) 137. Court of Appeal: Attorney General (Ontario) and Viking Houses v. Peel, 1977 CanLII 47 (ON CA); 16 OR (2d) 765; 36 CCC (2d) 337. Supreme Court of Canada: Attorney General (Ontario) and Viking Houses v. Peel, [1979] 2 SCR 1134, 1979 CanLII 48 (SCC); 104 DLR (3d) 1; 49 CCC (2d) 103; 29 NR 244.↩

- Supreme Court of Ontario, cited in note 2, above. ↩

- Supreme Court of Ontario: Unreported decision of Justice Van Camp, July 10, 1978. Court of Appeal: Regional Municipality of Peel v. MacKenzie et al., 1980 CanLII 64 (ON CA); 29 OR (2d) 439; 113 DLR (3d) 350; 54 CCC (2d) 244. Supreme Court of Canada: Regional Municipality of Peel v. Mackenzie et al., [1982] 2 SCR 9, 1982 CanLII 53 (SCC); 139 DLR (3d) 14; 68 CCC (2d) 289; 42 NR 572. ↩

- Justice Arnup in Court of Appeal decision cited in note 3 above. ↩

Re L.D.K. (An Infant): 12-year-old girl opposes blood transfusion

During the five days of this hearing, I have heard much about life and death. There is not one person in this room, and I imagine a great many others who are not in this room, who would want other than for L.D.K. to live.[1]

These are the words of Provincial Court Judge David Main in a case involving a 12-year-old girl – L.D.K. – who suffered from a fatal disease known as acute myeloid leukemia. As Jehovah’s Witnesses, L.D.K. and her parents were opposed, for religious reasons, to cancer treatment that would involve blood transfusions. L.D.K was also adamantly against chemotherapy and transfusions due to the pain and anguish she knew they would cause.

Judge Main found the young girl capable of forming a rational decision about her condition and the available treatment options. L.D.K chose not to take the treatment and died shortly after her court hearing in 1985.

A Child in Need of Protection?

The case began when the Children’s Aid Society of Metropolitan Toronto applied to the Provincial Court (Family Division) for an order that L.D.K. was a child in need of protection. If the judge agreed, she would be removed from the care of her parents and made a ward of the Children’s Aid Society – which would then have made treatment decisions for her.

A Hearing in the Hospital

Due to the child’s weak condition, Judge Main did not conduct the hearing in a traditional courtroom. For five days – the length of the hearing – the Court sat in Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, with L.D.K. wheeled down in her bed to listen and participate in the proceedings.

Wise Beyond Her Years

In denying the Children’s Aid Society’s request, Main made much of L.D.K.’s testimony. In his reasons for decision he said,

L.D.K. has told this court clearly and in a matter-of-fact way that if an attempt is made to transfuse her with blood, she will fight that transfusion with all the strength she can muster…. She has wisdom and maturity well beyond her years and …. a well thought out, firm and clear religious belief. In my view, no amount of counselling from whatever source or pressure from her parents or anyone else, including an order from this court, would shake or alter her religious beliefs. I believe that L.D.K. should be given the opportunity to fight this disease with dignity and peace of mind. That can only be achieved by acceptance of the plan put forward by her and her parents.[2]

A Pivotal Decision

As a lawyer, Heather Katarynych appeared in cases involving children whose families would not consent to certain treatments due to their religious beliefs. Later she presided over such cases as a judge of the Ontario Court of Justice. In her view, “David Main’s decision was a turning point in the Court’s approach to medical emergencies involving children. He focused on the capacity of the child – in this case a 12-year old – to make decisions about the treatment that the hospital and Children’s Aid wanted for her.”[3]

Judge Main made it clear that his was decision was based on the specific facts of the case. Those facts included a fatal disease which, even with the proposed treatment, had a 30% rate of cure and the prospect of extreme effects from “extremely toxic” chemotherapy drugs.[4]

The Children’s Aid Society did not appeal the decision. A Globe and Mail article explained that, “Bruce Rivers, service director for the Toronto branch of the Children’s Aid Society, said the society did not appeal the ruling because the girl was dying of leukemia in any case and had a short life expectancy.”[5]

The Media Weighs In

Judge Main’s decision garnered media attention. Here is how one journalist summarized the case.

Last fall, a Provincial Court judge in Toronto agreed that a 12-year old girl didn’t have to take painful chemotherapy treatment for leukemia because it offended the tenets of her religion and because the treatment offered only a small chance of success. The girl died a few weeks later.

(Source: “Do we have dying rights?” by Rick Hallechuk, Toronto Star, April 19, 1986)

A Courageous Person

In his decision, Judge Main described L.D.K. as “a courageous person.”[6]

The judge can also be seen as courageous in deviating from the approach often taken by the courts. As stated in an article in the Ottawa Citizen, just a few days after the L.D.K. decision, “In the past, courts have generally ordered the medical procedure be carried out on a child over the religious objections of the parents.”[7]

Conclusion: The Challenge Continues

Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice continue to hear cases involving disputes over blood transfusions and other medical treatment for children, each case presenting an emotional as well as a legal challenge.[8]

- Re L.D.K. (An Infant), 1985 CanLII 2907 (ON CJ); Children’s Aid Society of Metropolitan Toronto v. L.D.K. [1985] O.J. No. 803, para 27.↩

- Re L.D.K., paras 18, 33 and 34.↩

- Interview of H. Katarynych for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Re L.D.K., paras 3, 22, and 14.↩

- Marina Strauss, “Blood transfusion violated rights of girl, judge says”, The Globe and Mail, January 4, 1986.↩

- Re L.D.K., para 33.↩

- “Dying girl’s wish to avoid transfusions upheld by judge”, Toronto (CP), Ottawa Citizen, November 7, 1985.↩

- See for example: S.R. (Re), [1983] O.J. No 732, 36 R.F.L. (2d) 70, 21 A.C.W.S. (2d) 452; Children’s Aid Society of Metropolitan Toronto and F. et al. 66 O.R. (2d) 528 (1988); T.H. v. Children’s Aid Society of Metropolitan Toronto [1996] O.J. No. 5607; Children’s Aid Society of Toronto v. M.L. [2008] O.J. No. 4271, 2008 ONCJ 528, 59 R.F.L. (6th) 450, 2008, CarswellOnt 6358, 172 A.C.W.S. (3d) 676; Children’s Aid Society of Toronto v. L.P. [2010] O.J. No 3508, 2010 ONCJ 320, 2010 CarswellOnt 5999, 192 A.C.W.S. (3d) 176; Hamilton Health Sciences Corp., v. D.H., 2014 ONCJ 603. ↩