Fred Hayes: A Pragmatic Progressive

Robert James Kerfoot Walmsley: Long and Fondly Remembered

Joe Addison and Robert Dnieper

Ted Andrews: Getting Family Courts “Out of the Basement”

Gérald Michel – In His Own Words

Stories

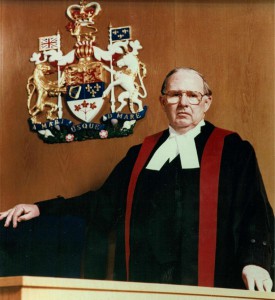

Frederick Clair Hayes: A Pragmatic Progressive

Before and after snapshots of Fred Hayes’ Court could not be more different. During his 18-year tenure as Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) – now part of the Ontario Court of Justice – a process of modernization began. The Court began its transformation from the “most neglected court in Ontario” to the respected face of justice for the people of the province it is today.

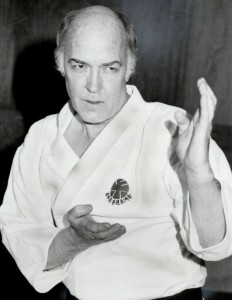

Frederick Clair Hayes was old school in an era of profound change – a stickler for protocol in a benighted court. This proud and dignified man took the helm of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in 1972. He used those traits and led by example to bring rigour and professionalism to the Criminal Court. Hayes did not seek out the many reforms that characterized his years as leader of the Court, but he embraced them and worked tirelessly to implement them.

Hayes’ Background: “Never Lost a Yard of Ground”

For Hayes, the commitment to public service ran deep.

Born in Arden, Ontario in 1924, Hayes was an only child, son of a family that moved around small-town eastern Ontario, settling in Tweed, where his father served as a police officer. “It wasn’t a wealthy family,” said his daughter, Joanne Hayes. “And this was something he always remembered – he was able to move up in the world, not only due to his skill, but through opportunities given to him.”

In 1942, Hayes volunteered to serve in the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders, a regiment that was known for “never failing to take an objective and never losing a yard of ground.” He served overseas with the regiment in Holland. Though he maintained a military bearing throughout his life, “he never talked about the war,” recalled Joanne Hayes. “But I believe that experience heightened his sense of public service and was one of the reasons he took the appointment to the Magistrates’ Court in 1961.”

Like many soldiers returning to Canada, Hayes benefitted from financial aid from the federal government to attend university, first at Queen’s University and, then, Osgoode Hall Law School. “Both my parents were helped with their educations to attend university,” explained Joanne Hayes, “and both were great advocates of education.”

Upon Hayes’ graduation from law school in 1953, he found a job in a general practice firm in Toronto. When he married Betty Monteith in 1954, the couple decided to settle in the city.

“He was never sure why or how he was appointed – he didn’t have any political connections. But when he was asked to become a magistrate, he took a pay cut and deemed it an honour to serve,” said Joanne Hayes. “He was always very concerned about ‘doing the right thing.’ He’d tell us to ‘never be in a position where someone would ask you for payback.’ He hated to compromise. He was very hard working. He arrived home every night with a briefcase in hand and there was always a stack of Ontario Reports beside his bed.”

Joanne Hayes laughed at one particular recollection. Hayes used to give his wife a break on Saturdays. He’d take their three children to court – where he’d be presiding – and sit them in the back of the courtroom, asking the court volunteers, often Salvation Army workers, to keep an eye on them.

Joanne Hayes laughed at one particular recollection. Hayes used to give his wife a break on Saturdays. He’d take their three children to court – where he’d be presiding – and sit them in the back of the courtroom, asking the court volunteers, often Salvation Army workers, to keep an eye on them.

In 1990 – following his tenure as Chief Judge – Hayes was appointed, by the federal government, to the Ontario Court, General Division. He worked until the end of his life – presiding in an attempted murder trial until the day of his death. He died in his sleep on October 24, 1994 at the age of 70.

The Court Hayes Inherited: “The Most Neglected Court in Ontario”

It is difficult to know where to begin when describing the Court back in the 1960s and early 1970s. As former Associate Chief Justice Peter Griffiths explained, “it was straight out of England of the 1850s.” This anachronistic situation was about to change, propelled by two key reports: the Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights (the “McRuer Report”) of 1968 and the subsequent Ontario Law Reform Commission Report on Administration of Ontario Courts of 1973. The provincial government of the day took the recommendations contained in those reports and translated them into significant changes to the court system in Ontario.

Both reports detailed a court system, comprised of benches of approximately 100 provincial magistrates and more than 900 justices of the peace[1], in crisis.

- Regional variations — The Provincial Courts were decentralized amongst various municipalities, counties and districts, meaning justice looked very different depending on where one lived in Ontario.

- Disorganized record keeping — In 1968, for example, the record keeping of the Court was so disorganized that the number of justices of the peace in Ontario was unknown. “The names of 925 appear on incomplete records but we are informed that there is in addition an unknown number whose names are not officially recorded anywhere…this situation makes a mockery of judicial office and is bound to depreciate respect for law and order in the community.” [2]

- Appointments as political rewards — Appointments to both benches were frankly political. In his report, McRuer condemned “without reservation and with all the emphasis at our command the appointment of justices of the peace as a political reward.”[3]

- Part-time magistrates — Despite hearing the vast majority of criminal cases (some 95% of indictable offences were tried by magistrates in 1965), magistrates often served part time, were often engaged in the practice of law or other business at the same time, and often had no legal training.

- Lack of training — Once appointed, magistrates and justices of the peace received little, if any, training for their positions. In fact, one justice of the peace reported to the McRuer Commission: “I know of several (justices of the peace) who have no knowledge of the laws with which they have to deal and who cannot even draw an information or bail bond, and simply sign the various documents drawn by other persons such as police officers.” [4]

- Low salaries and fee for service — Salaries for both benches were paltry. Justices of the peace were paid on a “fee for service” basis – a method criticized as “subversive to the administration of justices. The payment of judicial officers on a piece-work basis necessarily diminishes the public respect for law and order.” [5]Salaries for magistrates were deemed inadequate – of an amount that would attract “older men who may regard (the position) as a form of semi-retirement.” [6]

- “Police courts” — The Courts appeared to be dominated by the police – who often appeared, in uniform, as court staff. This had a significant impact on public confidence in the courts as a source of impartial adjudication. To further complicate this apprehension of bias, court proceedings were often conducted in police stations and jails. There were, simply, no other physical facilities to house the Court.

By the time Hayes took office as Chief Judge, some of the recommendations contained in the McRuer Commission Report had been implemented. In 1968, the Magistrates’ Court’s had become the Provincial Courts. Two new divisions were created – the Provincial Courts (Criminal Division) and the Provincial Courts (Family Division). Magistrates became known as judges. During Hayes’ tenure as Chief, minimum professional qualifications were specified for the exercise of certain powers or duties under the Criminal Code. A Judicial Council for provincial judges was created to advise the Attorney General with respect to new appointments, and to investigate complaints about the conduct of judges. Judges’ salaries began to increase to reflect responsibilities.[7]

All were critically important changes but they took time to implement.

In 1973, the Ontario Law Reform Commission noted: “Despite the changes effected in 1968, the status of the Provincial Courts (Criminal Division) in Ontario remains low.”[8]

This is the situation Hayes inherited in 1972 – things had begun to turn around, slowly and steadily.

The Power of Moral Suasion: “We Call Him Chief”

“The courts of justice, presided over by an independent judiciary, are the ultimate guardians of the civil rights of the individual.” – The McRuer Report

An independent judiciary is what makes the Canadian justice system the envy of the world. It does not, however, make a group of independent judicial officers easy to manage. It has been said that judges do not have a boss. That means the Chief Judge is simply the first among equals.

This management challenge was further complicated by the “somewhat loose structure” of the Court. The absence of a clear statement of the function and duties of the Chief Judge in the legislation establishing the Courts was noted as a significant problem by the Ontario Law Reform Commission in 1973. Apart from general supervision and direction over arranging the sittings of his Courts and assigning judges for hearings, back in 1973, the Chief did not have much in the way of management power, particularly when the majority of administrative functions were handled by the government. The Chief was expected to develop and maintain a “special relationship” and work with a provincial Director of Court Administration who retained control in matters relating to funding, collection of statistical information, and all administrative systems. [9] Judicial independence was one thing, administrative independence was something else.

This “loose” situation was compounded by the approach to the role of Chief taken by Hayes’ immediate predecessor in the role, Arthur O. Klein. Klein served as Chief Judge of the Magistrates’ Court for four years, beginning in 1964. Allen Edgar, who joined the Court as Research Counsel in 1980, recalled hearing stories about the differences between the two Chief Judges: “With Klein, it was ‘where does it say I have the power to do this?’ and with Hayes, it was ‘where does it say I can’t do this?’” In other words, Klein took a hands-off approach to the role. Hayes, on the other hand, was a hands-on Chief.

Hayes’ challenge was to become the first among equals – with very few real tools at his disposal.

Hayes – with his rigorous sense of protocol and imposing military bearing – understood that he was the face of the Court and that everyone was looking to him to represent the Court. It was his job to conduct himself – always – with honour and integrity.

Former Associate Chief Justice Peter Griffiths recalled his days as a Crown Attorney at Toronto’s Old City Hall when Hayes was Chief. “He had a wonderful presence…At swearing-in ceremonies, there’d be a lot of chatter in a packed courtroom. Hayes would walk in and just stand there. He’d look around the room – no smile, no words – until the room calmed down and was completely quiet. He carried himself in a judicious way, with great dignity.”

Hayes was known as a “one-man show.” Edgar recalled him as a “reluctant delegator.” Hayes worked tirelessly at centralizing the manner in which the Criminal Division and Provincial Offences Courts (created in 1979) operated. He did this the old-fashioned way, visiting as many courthouses, judges, and justices of the peace as often as he could – driving and flying around the province, particularly its far northern reaches, bringing his message of improving the Court and its services.

As part of the centralization and professionalization of the Court, Hayes instituted a system of “senior” judges and actively pressed the government to eliminate all part-time judges. During his tenure, legislative change made it mandatory for all judges to be lawyers with at least 10 years’ experience. Despite this requirement, he found many judges in his bench to be difficult to manage. Given the combination of principles of judicial independence and the limited tools at his disposal, Hayes ascribed to the philosophy of “keeping your friends close and your enemies closer.” To keep an eye on his “problems,” he often moved judges whose abilities were in question to sit in Old City Hall – the courthouse in which Hayes had his office. This had the unfortunate result of creating a bad reputation for Old City Hall. Because of its central downtown location and large size, newspaper reporters were often in attendance for some of the less-than-impressive behaviour of certain judicial officers. It made for lively press coverage. Despite these tribulations, Hayes was able to improve the reputation of the Court in ways that made the governments of the day sit up and take notice – and slowly and steadily increase the jurisdiction of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division), by giving it more Criminal Code offences that true Provincial Court judges had jurisdiction to hear.[10]

Some recall Hayes as “moving the Courts out of the jails and police stations,” an integral element of reinforcing the independence of the Court. Hayes did this – but only in part. He was also pushed along by his own justices of the peace and judges. Even in the late 1980s, weekend show-cause and bail hearings were often conducted in jails and police stations as opposed to courtrooms. The reason? The cost of keeping courtrooms open and staffed. The controversy? Court proceedings were being held in private, often without counsel, in places that were intimidating to the accused person and in rooms that Justice of the Peace Frank Devine described as “not conducive to conducting a proper court.” [11] To remedy this situation, a group of justices of the peace in Toronto began refusing to conduct bail hearings in police stations or jails, stating such practices infringed the accused person’s right to an open trial with the public present and legal representation. After several such refusals, the decision was made to open weekend “WASH” (Weekends and Statutory Holidays) courts across the province – no more weekend bail hearings within jails or police stations.

It is interesting to talk to people, like Edgar, who worked with Hayes. The discussion always veers back to Hayes’ presence and the fact that he was always the dignified and reliable face of his Courts – even in the early days, when the Court itself was pulling itself up from its trough of neglect. That dignity engendered deep respect amongst his colleagues. They didn’t always like him, but they respected him.

Justice Judythe Little wrote a tribute to Hayes soon after his death, which was included in the Court’s newsletter, Benchmark. “I think each of ‘his’ judges felt that we had his special support…Soon after my appointment, I was talking with Fred about something when we were joined by several other judges. In conversation, I referred to Fred by name. One judge asked me querulously why I was calling the Chief Judge ‘Fred.’ I replied immediately that I called him that because Fred was his name. Fred chuckled with delight. Later, I found out that most of the judges called him ‘Chief.’”

Commitment to Education

Hayes was committed to elevating the professional level of the judges and the justices of the peace to ensure a fully competent Court. He wanted to create a criminal court of the finest reputation for Ontario.

Education was his primary tool. But he had a couple of big hurdles to overcome. First, educational programming was new for the Court – neither judges nor justices of the peace had received any formal training for their positions before he became Chief. Second, he had to beg the provincial government for the money to provide any educational programming. The purse strings were held by the government and if Hayes wanted to deliver a program, he had to ask – and, many times, he was turned down.

But, Hayes was a “make-it-work” guy, according to Doug Ewart, who worked for the Ministry of the Attorney General as legal counsel and, then, as director of the Policy Development Division of that Ministry.

Through his own efforts, Hayes used a simple practice to educate the judges. He would get copies of all of the reported Court of Appeal and Supreme Court of Canada cases. He’d go through them, mark them up and then distribute, to the bench, the portions that he felt his judges needed to see. He was always conversant with the leading cases. Justice Gerry Michel recalled the “excellent example” Hayes set for all to follow.

Another approach was his “on-the-job” education method, which many of those who worked with Hayes recall. Justice Michel remembered Hayes’ open-door policy and natural teaching abilities. “He was the ‘go-to’ guy if you had any sort of legal question. He never actually told you what to do, but he would always spend the time with you to ask you questions that would lead you to the answer, or at least get you thinking about the issues you needed to consider.”

Justice of the Peace Brian Hudson had a similar story to that recounted by Michel. Hudson began his career as a court clerk and met Hayes then. “He treated everybody with the same respect. He expected the same intellectual engagement from his clerks as he did from himself – and he spent time ensuring it.” Hayes worked with his clerks to teach them the criminal law they needed to know in the courtroom. “He relied on you – as a clerk – to know the Criminal Code. And if you weren’t up to snuff, you didn’t work with him. We all respected him for his command of criminal law and his ability to work – he did the work of four people…And, he made you feel that working for him was like going to law school.”

When Hayes could get funding, he provided formal programming for both judges and justices of the peace. He worked with the University of Western Ontario to create the “University Program” for the judges – a week-long intensive program in which a group of judges would return to law school, and a set of lectures by law professors. He also instituted the “Sentencing Seminars,” in which judges would gather and consider cases and discuss what sentence they might hand down. Again, Hayes knew his crowd and had carefully considered his motives.

Judging is, by its nature, a lonely occupation. These Sentencing Seminars not only encouraged a collegial attitude amongst the judges but they also served as a way of making decisions more consistent, without treading on the judicial independence of the judges. This, in turn, built public confidence in the Court. The governments of the day took notice.

By continuously strengthening the professionalism of his Criminal Division bench, Hayes built, day by day, issue by issue, the confidence that led defence counsel and Crown Attorneys to increasingly opt to have matters heard in his Court whenever the law gave them the choice. That, in turn, led legislators to regularly change legislation to increase the availability of that choice and increase the jurisdiction of Provincial Court judges. In the result, the face of criminal justice in Ontario was changed forever, and today the Ontario Court of Justice is known as the specialist court in criminal matters.

Women on the Bench

In 2015, women account for approximately 33 per cent of the judges and approximately 47 per cent of justices of the peace in Ontario. Back in the early 1970s, women were a rarity on both benches. It was during Hayes’ tenure that women began to be named to the Court. Judge June Bernhard, the first female judge, was appointed to the Criminal Division of the Provincial Court in 1979.

“Fred was one of the old guard,” recalled Justice Mary Hogan, appointed to the Criminal Division of the Provincial Court in 1987. “He knew he was hamstrung by his old school ways and he worked at trying to move with the times.” Hogan’s early days on the bench speak volumes about Hayes’ internal dilemma. Unbeknownst to Hayes, Hogan was pregnant with her third child when she was appointed to the bench.

She approached him soon after she became a judge. “I have something to tell you – I’m pregnant. You could see Fred thinking: ‘What am I going to do now?’ He sat quietly for a while, then he asked me when I was due. And that was that, we just carried on…Fred was nervous as I got bigger and bigger. He’d hang around my courtroom. And I’m sure he thought I’d breastfeed on the bench!” As it was, Hogan delivered her baby on Friday and was back in court on Monday. These were the days before maternity leave for judges. Hogan brought her daughter to work in a portable crib. Nobody commented. Shortly after Hogan’s daughter was born, the judges’ association, while negotiating salaries with the Attorney General, added maternity leave provisions to the list of items negotiated.

In the 1980s, women began to feel they might have a chance to become a judge or a justice of the peace. Hayes, in his way, encouraged that. Judythe Little, who sat in Kenora from 1986 until 2011, recalled Hayes telling her – before she was appointed – that he was looking forward to having more women appointed to the provincial bench and that there would soon be a number of women with the necessary 10 years’ experience as a lawyer. “That day we began a relationship from which I drew a lot of strength in my work as a judge,” she stated.

Both Hogan and Little told stories of the support they received from Hayes – but the support was not overt – again perhaps reflecting Hayes’ conflicted approach. Little recalled an educational seminar in the 1980s, where “the ‘guys’ were busy testing the new ‘lady judge’s’ approach to sentencing. I like to think that I held my own nicely. I remember Fred watching the exchanges with a great gleam in his eyes and a small smile on his face, as he sat back with his arms crossed.”

Hogan recalled the “days she was finally accepted by the judges at Old City Hall.” “I didn’t believe in sending traffickers who were addicts to jail and I was being constantly overturned.” The police weren’t pleased with Hogan’s approach and the media was carefully scrutinizing her sentencing decisions. Hayes’ approach was to take Hogan out of Drug Court and reassign her. Hogan remembered it all came to a head in the lunch room where she and Hayes had a serious shouting match. “He wanted me out of Drug Court and I refused. He wasn’t mean about it – and I held my ground. He respected that and so did the other judges.”

As Hogan told it, this was a Court where you had to make it on your own merits. It was not always an easy line to walk but Hayes ensured that the climate at the Court was welcoming to all.

Embracing Social Change: Northern Justice

Many times, Hayes was pushed – willingly – into adopting a progressive approach. Many times, he pulled the Court into new directions.

Joanne Hayes recalled that her father respected and understood Aboriginal traditions. “He always said that there might be different ways of delivering justice.” His commitment to the northern regions of the province was legendary. He travelled north often, bundled in parkas and boots. According to his daughter, “he felt responsible to the people there and the judges. They needed to see him.”

Hayes personally led an enormously important initiative: Ontario’s Native Justice of the Peace Program. At a time of widespread discrimination, and well before many Aboriginal people succeeded at law school and joined the legal profession, this program provided the first sustained and supportive program to bring Aboriginal people into presiding positions in Ontario’s courts.

Remarkable in its grass-roots foundation and its audacity, the program worked with and within Aboriginal communities to identify people who, though lacking formal qualifications, clearly had the intelligence, integrity and judgment to become fine judicial officers. The program did not allow the lack of justice system knowledge or other formal qualifications to bar their accession to such positions. Rather, the program provided intensive, in-person pre-appointment training so that those gaps could be filled, and that fully qualified individuals could be considered for appointment as justices of the peace.

The personal commitment of Hayes to this initiative, long before others were doing anything like it, shows his understated and too-often unacknowledged dedication to the highest principles of justice. While Aboriginal people make up nearly three per cent of the Canadian population, more than seven per cent of the justices of the peace in Ontario in 2015 are Aboriginal. In keeping with his “one-man operation” approach, when Hayes sent a judicial officer to the northern reaches of the province in winter, he’d personally approach the government and ask for funding to provide the requisite parka, insulated boots and sleeping bag.

Keeping Ahead of the Torrent

“Hayes’ office was where he was,” explained Griffiths. In the 1980s, Griffiths was a Crown Attorney in charge of scheduling all the Crowns in Toronto and assigning cases to them. In those days, he was watching the trial lists grow longer and longer (due in part to the introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982). “I’d meet up with Hayes in the hallways of the courthouse. If it was the beginning of a month, he’d always take me aside and tell me he had ‘good news,’ despite his ever-growing number of cases. Then he’d pull a handwritten list out of his jacket pocket where he’d hand counted every case – thousands of them – in every court house in Ontario. It was right out of the 1800s. But he was always positive – he was always trying to reduce the backlogs.” Hayes was stymied in this by the Court’s lack of control over funding and, therefore, the ability to keep statistics and modernize record-keeping processes – and keep ahead of the growing backlog.

In so many ways, Hayes was the victim of the success of his Criminal Court. As its jurisdiction increased and criminal cases flooded in, the administrative structure simply wasn’t there to process them effectively. Some of those necessary administrative changes would come later, with the Chiefs who followed Hayes.

By the time Hayes left office, the Criminal Division of the Provincial Court and the Provincial Offences Court were unrecognizable from the ones he had inherited. The judges were appointed through what is still the most neutral and independent process in the country. They had the jurisdiction to, and did, preside over almost all of the most serious criminal cases in the province. The justices of the peace had been brought under the wing of the Court and were on the road to professionalism and independence.

- Prior to 1968, the provincial government appointed three different types of judicial officers: justices of the peace, magistrates and family judges. At the time of the McRuer Commission, justices of the peace could exercise powers in taking informations, issuing warrants, granting bail and when presiding at the trial of summary offences. Magistrates had the jurisdiction to try, with the consent of the accused, all indictable offences, save only those few extremely serious offences which were tried in the Supreme Court of Ontario. Magistrates also presided at the trial of summary offences, including breaches of the Highway Traffic Act, the Liquor Control Act, and municipal by-laws. In 1968, when the Provincial Courts (Criminal Division) was created, three Provincial Courts (Family Division) was also created. Its Chief Judge was Ted Andrews.↩

- McRuer Report (Report No. 1, Vol. 2, 1968), p. 516, p. 518.↩

- McRuer Report (Report No. 1, Vol. 2, 1968), p. 519.↩

- McRuer Report (Report No. 1, Vol. 2, 1968), p. 520.↩

- McRuer Report (Report No. 1, Vol. 2, 1968), p. 523.↩

- McRuer Report (Report No. 1, Vol 2, 1968), p. 529.↩

- Provincial Courts Act, 1968, S.O. 1968, c. 103; Ontario Law Reform Commission, Report on Administration of Ontario Courts, (Part II, 1973), p. 3.↩

- Ontario Law Reform Commission, Report on Administration of Ontario Courts, (Part II, 1973), p. 3↩

- Ontario Law Reform Commission, Report on Administration of Ontario Courts, (Part II, 1973), p. 20-21↩

- In the years since the McRuer Report, numerous legislative and policy decisions have been made by the federal and provincial governments which have systematically increased the criminal jurisdiction of the Court, reduced the exclusive jurisdiction and workload of the Superior Court in respect of criminal matters and made the Ontario Court of Justice, for all intents and purposes, the major and dominant criminal trial court for the province. Approximately 98% of the criminal case load in Ontario is finally disposed of in the Ontario Court of Justice.↩

- All quotes of various individuals including J. Hayes, P. Griffiths, A. Edgar, F. Devine, B. Hudson, D. Ewart, M. Hogan, G. Michel, were from interviews conducted with them for the OCJ History Project in 2013-15.↩

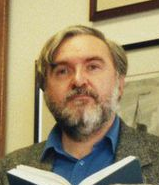

Robert James Kerfoot Walmsley: Long and Fondly Remembered

NOTE: This profile was written by Justice George Brophy and Professor Peter Walmsley, “Bob” Walmsley’s son and George Brophy’s son-in-law. Professor Walmsley is a professor of English at McMaster University.

Robert James Kerfoot Walmsley was born on November 25, 1927 in Picton, Ontario, the county town for Prince Edward County. His mother, Helen Kerfoot, was a teacher and his father, Gordon T. Walmsley, was a lawyer. The Walmsley law firm had deep roots in Prince Edward County having been founded by Robert Walmsley’s grandfather in 1889.

Robert Walmsley received his initial secondary school education at the University of Toronto Schools and then at Kingston Collegiate and Vocational School and the Picton Collegiate and Vocational Institute, graduating from Grade 13 with first-class honours. Robert Walmsley attended Trinity College at the University of Toronto from 1946 to 1950 and Osgoode Hall Law School from 1950 to 1954, after which he joined the Walmsley law firm. He practised in Picton with his father upon his call to the bar and was later joined in the firm by his younger brother Douglas in 1963.[1]

Robert Walmsley married Ruth Linell in 1952, whom he had met at the University of Toronto. Together they had four children: Ann, John, Peter and Benjamin.

As a local lawyer, Walmsley was actively involved in community life, sitting on Picton’s town council as well as serving as a school trustee and on the library board. He also sang in community productions, much as he had done at university.

Walmsley was first appointed to the bench in 1965 as an acting family court judge. In 1967 and 1968, he served in the same capacity on a part-time basis for Prince Edward County. In 1968, he became the full-time magistrate and family court judge for Hastings, Lennox and Addington Counties and Prince Edward County, and then, in keeping with the changes in the structure of the courts, was appointed in 1968 as a full-time judge in the Provincial Court (Family Division).

In June 1977, he was named Senior Judge for the eastern region of Ontario and, in September 1978, he became the Associate Chief Judge of the Family Court, a position he held until 1992, when he retired as a full-time judge. Thereafter, he sat as a per diem judge until he reached the age of 75.

During his career on the bench, Walmsley served in many different capacities. He was president of the Provincial Judges’ Association (Family Division) from 1974 to 1975 and was a member of the board of that association from 1969 to 1978. He was also a member of the Canadian Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and participated in and contributed to many legal and community conferences, including lectures to students at Queen’s University Law School, Loyalist College and Trent University.

Throughout his legal career, Robert Walmsley was a member of the International Commission of Jurists, having first joined in 1955. He was also a member, from time to time, of the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice and the Canadian Bar Association (where he served both as a member of the Council of the Ontario Branch and on the National Council).[2]

In the course of a judicial career that spanned over 37 years, Robert Walmsley wrote and delivered many judgments, 66 of which are still available on LexisNexis. He was a “judge’s judge and a lawyer’s judge,” observed his long-time colleague and friend Justice James Felstiner. “His judgments were very well written, logical and sensible.”[3]

However, it was as an administrative judge that Associate Chief Judge Walmsley made his most lasting contribution. The Chief Judge of the Family Court, H. Tedford G. Andrews, asked him to oversee some of the most important developments in that Court. Those tasks included convincing the Attorney General of the day that appointees to the Court had to be legally trained, relocating family courts out of the basements of Ontario, figuratively and literally, and establishing continuing education programs for the judges.[4]

Robert Walmsley served as a special advisor on family law to the Chief Judge and provided substantial input into new legislation, including the Young Offenders Act, the Family Law Reform Act and the Child and Family Services Act. He was involved in the development of continuing education programs for Family Court judges and acted as a mentor and support for judges.

He also lobbied for an increased number of judges to deal with delays in the administration of justice on the family side. Walmsley, alongside Andrews, took what was then an unusual step for judges by publicly expressing their concern in the media about delays in the family courts. He told The Globe and Mail that “a young child’s interest could very well be to stay where [the child] is, because [the child] becomes psychologically attached. So you have decisions dictated to you by the passage of time. It is unfortunate to the parents, the foster parents and everyone involved.”[5] This public relations effort made the case for a greater investment of resources into family law. Andrews maintained that Robert Walmsley’s contribution to the evolution of family justice in Ontario cannot be overstated.[6]

Later in his career, Walmsley became involved in the process for appointing judges to the Provincial Courts. In 1988, he was asked to join a judicial appointments committee established for a three-year project by Attorney General Ian Scott. This committee was charged with seeking out qualified candidates from the legal profession, but particularly those from groups not then ordinarily represented on the bench – women, visible minorities and aboriginals. This eventually led to the establishment of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee (JAAC). In 1991, within a year of the merger of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and the Provincial Court (Family Division) into the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division), Walmsley was asked to act as the chair of that committee.

The work on the JAAC committee was the highlight of Walmsley’s career in that it allowed him to play a major role in the direction of the Court. He worked tirelessly to develop the process and procedures by which the committee functioned. Dozens of judges were interviewed by the committee as judicial applicants during his time as chair, and they universally remember him as a soft-spoken, kind and understanding man whose words of encouragement before and after their interviews helped ease the stress of the experience.[7]

A surprising issue that arose out of that role was the question of whether committee members were able to keep their notes and records private. This became an issue in the case of Walmsley v. Ontario (Attorney General).[8]Robert Walmsley was the named respondent in an application brought for discovery of those records. The Ontario Court of Appeal decided that the members of the committee were not employees or agents of the province and their records were not discoverable. This decision enhanced the independence of the committee from the executive branch of government and thus supported judicial independence. Aside from the principle that was upheld, this decision was of considerable relief to Walmsley because of his habit of drawing portraits of people appearing in front of him – he used the sketches to help him in reviewing cases – and because he had a penchant for composing rhyming verses in his notebook. He certainly would not have wanted his sketches and poetry to meet the public eye in the glare of a lawsuit.

Not lost on Walmsley was the importance that attention to detail played in the JAAC committee process. Along with its efforts to attract well-qualified candidates from all parts of the society it served, the reformed appointment process was vastly different from that which was in place when Robert Walmsley was a young lawyer. He often remarked that the new and better appointment protocols would have made his own appointment to the bench far less certain.

Walmsley brought to the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee the good humour and empathy that was his trademark characteristic. Justice Rosalie Abella of the Supreme Court of Canada, who met Walmsley in 1976 when she was appointed a Family Court judge in Ontario, said: “Bob was an extraordinarily warm, compassionate and wise man.” She added that “he took care of all of us on the Court – intellectually, collegially and institutionally. … He was one of the most literate people I knew, his exceptional cerebral talents were matched by a fantastic sense of humour. He was funny, laughed easily and often, and never failed to find the right deflationary retort to any whiff of pomposity.”[9]

Chief Judge Andrews remarked upon the personal adaptability of Walmsley, who had reinvented himself from a rural Family Court judge in a single-judge location, to one of the most popular and beloved management judges in the history of the Court. As remembered by Andrews, “Bob” – as he was known to his colleagues – was everyone’s “grandfather, compassionate, understanding, incredibly supportive and always ready to soothe everyone’s woes with a kind smile and a word of encouragement.” Andrews found him to be “a dear friend and colleague, an exemplary judge, a wonderful husband and father, and a model citizen.” [10]

Justice Felstiner remembered aspects of Walmsley’s retirement that illustrate his personality. They often met for lunch and he noted:

Bob had an insatiable curiosity about new places, food (were the olives Greek or Italian?), waitresses’ careers, city happenings, new neighbourhoods, old neighbourhoods – especially old Toronto neighbourhoods with their remaining substantial homes from the 19th century. We always drove slowly – peeking here, going down that alley, stopping to watch cranes lift things high onto new condos. A typical scene: at the end of lunch I would go get my car, park it illegally, smack dab in front of the restaurant to make it easier for Bob [as a youngster a severe infection in his hip left him with a pronounced limp for the rest of his life], and I’d go in to get him. Rarely was he alone; it was hard to pull him away from his conversations with the cashier or waiter, and then he always, always stopped to read the brochures available as we went out the door. Then on the street he would say, “Oh there’s a Korean bookstore, I’ll just look in the window.”[11]

In his retirement, Walmsley mentored elementary school students and read to young children in the school library. This love of reading was not unusual for him because he was “enamoured of words (he memorized poetry and did cryptic crosswords from the Manchester Guardian for years) and so friendly to the whole world around him.”[12]

He also loved spending time at the family cottage in Prince Edward County where he had spent so much of his life enjoying the opportunity to sail and canoe. “He had an absolutely flawless J-stroke with the paddle”, his daughter Ann Walmsley reported.[13]

Robert James Kerfoot Walmsley died November 18, 2008, in his sleep at his Toronto home. He was 80 years old. He was survived by his wife, his children and 12 grandchildren.

In 2002, Chief Justice Brian Lennox wrote these words in a letter to Walmsley on the occasion of his 75th birthday:

The judges of the Ontario Court of Justice owe an immense debt to you in the various capacities which you have occupied in the course of the evolution of our Court. You have not only witnessed, but you have been a leading actor in the entire modern history of the provincial courts of Ontario. You have done so with dignity, grace, wisdom, humour, energy and enthusiasm. It is given to very few people in the course of their lives to have made such a significant contribution … When the history of the provincial courts of Ontario is written, you will be long and fondly remembered and will have a place of honour.[14]

- Indeed, the firm continued into the 21st century under the guidance of Justice Walmsley’s brother, Douglas, who practiced law for 40 years and who died in 2007 at the age of 71.↩

- February 1982 Curriculum Vitae, Archives of the Chief Justice.↩

- The Globe and Mail, December 29, 2008.↩

- Benchmark, Vol.17, No.4 – Winter 2008, p. 2.↩

- The Globe and Mail, op. cit.↩

- Benchmark, op. cit. p 2.↩

- Letter dated August 11, 1993 from Chief Judge Sidney B. Linden to Associate Chief Judge R.J.K. Walmsley.↩

- 34 O.R. (3d) 611, [1997] O.J. No. 2485.↩

- The Globe and Mail, op. cit.↩

- Benchmark, op. cit., p. 2.↩

- Benchmark, op. cit., p. 2-3.↩

- Benchmark, op.cit., p. 2-3.↩

- The Globe and Mail, op. cit.↩

- Letter dated November 25, 2002 from Chief Justice Brian W. Lennox to R.J.K. Walmsley.↩

Joe Addison and Robert Dnieper

Introduction

In 1986, Canadian author, Jack Batten published Judges – a collection of profiles which the author described as being “about Canadian judges at work.”[1] He took several Provincial Court judges as subjects and concluded that Provincial Court was where the “scrappy, visceral stuff takes place.” Batten observed that on any given day in court: “a judge is routinely called on to exhibit the tact of a diplomat, the wisdom of Solomon, the patience of a peace negotiator.” He interviewed numerous judges who were presiding in Toronto’s Old City Hall – a building Batten characterized as “everybody’s blithe and eccentric aunt. It just misses dowdiness, but for quirkiness it’s right on target.”[2]

Several of the Old City Hall judges profiled were quirky in their own rights. In particular, Judge Robert Dnieper was possessed of a significant reputation when Batten chose to write about him. A judge for 25 years by 1986, Dnieper was routinely identified by the media, lawyers and others as one of “the worst” in the Provincial Court system.[3]

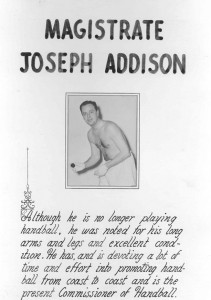

Batten also interviewed judges whom he unabashedly admired for being “courteous, bright, determined and industrious.” “Gentleman Joe” Addison was placed squarely in that category by the author.

Jack Batten’s profiles of Addison and Dnieper are excerpted in the following paragraphs.

Judge Joe Addison

As an introduction to the excerpt from Judges, Jack Batten has penned this postscript to his profile of Joe Addison:

“At Joe Addison’s funeral on Sunday afternoon, September 6, 1986, the rabbi spoke first.

‘Our friend Judge Joe Addison died a happy man,’ the rabbi began.

Then he explained why Judge Joe Addison had been happy. It happened that a few days earlier, the judge had got his hands on an advance copy of the book published later that month with a simple title, Judges. The book offered a series of thirteen profiles of judges at different levels of Canadian jurisprudence. One chapter was all about the Chief Justice of the British Columbia Court of Appeal. Another told the story of a Saskatchewan trial judge whose life might have been under threat from a man who had appeared before him. And another chapter tried to portray the entire Supreme Court of Canada.

Then there was the chapter titled ‘Joe Addison.’ It told Judge Addison’s story from the time he was appointed to Ontario’s Provincial Court in 1958. On the bench, Judge Addison was fair, kind, well-versed in the law, and often very funny. He treated everybody who appeared before him with grace. It was not for nothing that the nickname by which he become known around the courts was ‘Gentleman Joe.’

Judge Addison took his advance copy of Judges home to show his family. He was seventy-four at the time, still sitting on the bench, still counting on a few more years of life. That night, he gathered his family together, and read to them the chapter about him from the book. He was pleased with what he read. So was his family. It made him and them feel proud of the work he had done and was still doing.

Joe Addison went to sleep that night a happy man. Since the judge never woke up from the sleep, since he died in the night, the rabbi at his funeral must surely have been right when he said Judge Addison died a happy man.”

Thus, the words which so pleased Joe Addison in Jack Batten’s Judges are excerpted below:

Addison has been a Provincial Court judge since 1958, sitting almost exclusively in Toronto’s Old City Hall, and in all his years on the bench, he’s taken a sort of bemused attitude toward the bizarre and terrible events that happen in front of him. He’s a funny man, and he likes to laugh on the job. But there’s nothing condescending or cruel about his wit. He doesn’t score points off the people in the prisoners’ box. He doesn’t take advantage.

“I’m not gonna go out there resenting the guys who appear before me,” he said one spring morning in 1985, sitting in his chambers at Old City Hall. “I don’t shake my finger at them or give them a lecture. They know what’s gonna happen to them anyway. In a lot of cases, most likely they’re going to jail.” There are a couple of other points about Addison. One is that he’s a gracious man. He isn’t known among defence counsel as “Gentleman Joe” for nothing. And the other is that he’s got the art of judging down as fine and fair as it will go. Around Old City Hall, they say that Joe Addison has never been reversed on appeal. It’s hyperbole, but it’s a measure of the man’s honestly won reputation.

“Everybody gets a good trial from me.” Addison said. “The fella may not like the result, but he can’t complain he wasn’t treated right. I’ve always told my associates on the bench, if I was a person who wasn’t guilty of something I was charged with, I’d rather appear before me than any of them….

In the catalogue of the thousands of cases he’s heard, Addison looks back on the David Winchell hearing as one he got a special laugh out of. Several laughs. Winchell was a stock promoter around Toronto, and in the late 1970s he was peddling an unlisted oil stock to a number of the city’s big shooters. Winchell’s adviser in the deals was a lawyer named Sam Ciglen, who had had his own troubles with the law over the years. He had made many trips to court to defend himself against charges of stock fraud. But in the Winchell case he was mainly on the sidelines, which isn’t to say he didn’t reap a few benefits from the association. “The two of them, Winchell and Ciglen, used to go back and forth to Switzerland like I go downtown,” Addison says. “Switzerland must’ve been where they had a bank account for the money from the issue of this crazy stock.”

The money was substantial, about six hundred thousand dollars before the big shooters began to get nervous and called in the fraud squad. Charges were duly laid against Winchell, though not Ciglen, and the preliminary hearing in the case came before Addison.

“The fellas with the important names who lost money testified for the Crown,” Addison says. “DelZotto. Rudy Bratty. First time I ever saw those fellas look unhappy.”

A Crown witness named Sherkin, one of the other investors who’d dropped a bundle, took the stand.

Sherkin looked over from the witness-box to Addison. “Goodie sends his regards,” he said.

Winchell’s lawyer, an excellent counsel named Mike Moldaver, sprang to his feet and asked to see Addison in his chambers.

“What’s the trouble, Mike?” Addison asked when they were alone.

“The witness, Sherkin,” Moldaver said, concerned, “he’s a close friend of yours?”

“Mike, I never saw the man before in my life.”

“But what about this Goodie he’s talking about?”

Addison explained.

“He’s talking about Goodie Rosen, Sherkin is,” he said. “Goodie’s a wonderful guy. Used to play baseball for the old Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1940s. I grew up with him down by Bellwoods Park. Sherkin’s a friend of Goodie’s, I guess, and so am I. I got no control over what the witness says, but there’s nothing wrong here.”

Moldaver was mollified and returned to court.

Sherkin wasn’t through.

“Winchell used to take us investors up to his summer cottage and ride us around in his boat,” he testified. “That cottage, the Taj Mahal is smaller even, and his boat, you could float the Queen Mary inside it.”

Sherkin said he’d invested so much money in Winchell’s stock that his wife had worried herself into a heart condition.

Sherkin looked over at Winchell in the prisoners’ box.

“So what are you selling today, David?” he said. “Cancer?”

As the preliminary hearing progressed and as the evidence accumulated against Winchell, Moldaver entered into plea-bargaining with the Crown. They worked out a deal and took it to Addison for his approval. Winchell would plead guilty and accept a fine of one million dollars and repay the investors to the tune of some six hundred thousand dollars.

“I agree,” Addison said to the lawyers. “How would it help these investors get back their money if Winchell went to jail for three or four years? Wouldn’t achieve a thing.”

The bargain was struck, and a day later, a court official knocked on the door to Addison’s chambers.

“You want to look at something amazing?” the official said.

“Show me.”

The official held out a cheque.

“It’s from Winchell.” He said.

“One million bucks,” Addison said. “Certified. How d’ya like that? He came back with it overnight.”

“Ever seen one like that?” the official asked.

“Don’t move in those circles,” Addison answered…

Addison’s chambers are in a large, gloomy room at the top of Old City Hall. They’re furnished in pieces that might have come from a thrift store—a desk, a couple of armchairs, a sofa, and a coffee table. On the coffee table on this day there rested two fat volumes with blue covers, each volume about an inch and a half thick.

“My judgment from the preliminary hearing on the Southam case,” Addison said, gesturing at the blue volumes.

The Southam case is one of Addison’s prides. The hearing stretched over several months in his court, and he estimates he read “probably twenty thousand pages of cases” before he wrote his long judgment. The case involved important issues and big names in Canada’s corporate community, and it arose out of a series of transactions worked out by the country’s three leading newspaper publishers. Over a short period of time in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, the three dealt in several big-city newspapers in ways that attracted the alarm of the federal Attorney General’s Office. In Montreal, FP Publications closed down the Star and left the daily field to the Gazette, a Southam paper. In Winnipeg, it was a Southam paper, the Tribune that folded, leaving a Thomson paper, the Free Press, all alone. In Ottawa, the Journal ceased publication and turned the market over to a Southam paper, the Citizen. And in Vancouver, both newspapers continued operations, the Sun and the Province, but Thomson assigned its half-interest in the company that owned the two, Pacific Press, to Southam. The federal government regarded all of this manoeuvring as a form of hanky-panky and charged Southam, FP, and Thomson with offences under the Anti-Combines Act.

“I didn’t know I was taking the preliminary hearing in the case until the morning I walked into Forty-two Court,” Addison said in his chambers. “This was in the fall of 1981, and I looked at the counsel table and what I saw was the A-Team. I knew it was gonna be something very large.”

The evidence was complex, and the issues were new to Addison. “I’d never been down that road before,” he said. The hearing lasted through the winter until Easter of 1982 with a few weeks off from time to time while Addison and counsel tended to other cases and other trials. Addison did his homework on anti-combines law, and, as the hearing progressed, it seemed to him that there would probably be enough evidence to commit the newspaper chains to trial on the charges.

Jake Howard, Southam’s counsel, must have seen the writing on the wall. He elected to put in no defence on behalf of his client.

“Mr. Howard, do you have an argument?” Addison asked him in court.

“Your honour,” Howard said, “I didn’t have an argument in the beginning.”

Addison laughed. It was his kind of answer.

When the hearing ended and Addison retired to write his judgment, he found himself with new problems. Who, for example, was going to type his judgment?

Writing the judgment was challenging enough. “Many a night I’d wake up at four in the morning with something on my mind,” he said. “I’d get up, go to the den at home, and write until I got it all down.” The writing took up several four-in-the-morning sessions and most of the rest of Addison’s time. “I went to our chief judge, Fred Hayes,” Addison said, “and I said to him, ‘you may be wondering what I’m doing,’ and then I said, ‘I may be writing a novel.’”

Addison finished the judgment in longhand and went looking for someone to type it.

“The crazy problems you have in my business,’ he said. “I had a secretary, but she also worked for four other judges. I gave her the judgment and three weeks later it was still sitting in the same place. So I told her to farm out parts of the judgment to other stenographers. That didn’t work. Totally disjointed. Do guys in the Supreme Court of Canada have this kind of trouble? Next we brought in the good legal secretary who happened to be on the loose and got her to type it. At first there was a small difficulty. Her desk was beside the kid who delivered the mail. He smoked. That bothered the secretary. I got her a new office. By then I’d already had to postpone the day I said I’d deliver the judgment. It’s crazy, but that’s life in the Provincial Court.”

Addison’s judgment added up to 477 typed pages and it took him three days in early May of 1982 to read his words to the lawyers and reporters assembled in Forty-two Court. “Regrettably,” he began, “I have been unable to condense this judgment to other than gargantuan proportions.” Then he proceeded to analyse the evidence and the law on combines in immaculate detail. He concluded that the newspaper chains must face trial on the Crown’s charges.

Much later, at the trial in the Supreme Court of Ontario, the presiding justice dismissed the charges against Southam, FP and Thomson. He based his judgment on fact rather than on law. As a finding of fact, the justice held that the newspaper executives had no intent to break the law, that they had arrived at no prior arrangement to give themselves or the others an advantage in the various newspaper markets. Since the finding was based on fact, not law, the Crown was not able to make an appeal of the decision to a higher court.

Addison wished that the case could have been proceeded to appeal. He would have liked to see his own conclusions thrashed around in the Ontario Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada. That was one disappointment the case left him with. And there was one other tiny, niggling regret.

“I wish I’d bought some Southam stock,” he said in his chambers. “These guys had just created a gold mine. The stock was bound to go up, and after I’d finished my judgments, which of course was contrary to where my money would be going, I thought about investing. But then I figured, no, I better not touch it. The thing about being a judge is you can’t do anything that wouldn’t look right.”[4]

To balance Batten’s profile of Addison, it is interesting to consider the writings of one of Joe Addison’s peers on the bench at the time. Judge David Vanek was appointed to Magistrates’ Court a decade after Addison. Much had changed during those 10 years and Vanek had a different approach to judging than Addison. Vanek was more concerned with judicial independence than Addison who came from the culture of the “Police Magistrates’ Court,” where there had been a close relationship between police and magistrates.

According to Vanek, “Joe was infected by the magistrates’ syndrome. I considered Joe too close and friendly with the police. While there was nothing wrongful in this relationship, I felt it was desirable to avoid even an appearance of influence over a judge by persons associated with the justice system. I recall sitting in court with Joe Addison as part of my initial orientation when, in the course of the day, an accused came before him and pleaded guilty to the possession of a concealed weapon. He was a black man, had come from Buffalo by car, and had been stopped by police who found a loaded pistol in the car. I believe it had been affixed to the engine. The accused made an elaborate plea for leniency on grounds that because of the incidence of crime in the United States, it was necessary and acceptable to be in possession of a firearm for personal protection. He was under the impression that the law and the need for protection were the same in Canada. Joe Addison listened impassively, then simply spoke two words: “Six months!”[5] Vanek’s comments clearly demonstrate the maturing professionalism of the bench, with a growing concern about judicial independence.

Judge Robert Dnieper

So, why is someone known for being — in Jack Batten’s words — “a loose cannon” included in the court’s history? A profile like this one about Judge Robert Dnieper is a good reminder of where the court came from, the serious challenges it faced in the past and a strong admonition of where the court should not tread again – thanks to much improved appointments, review and education processes now in place for all judicial officers.

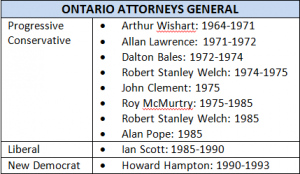

Dnieper sat prior to the adoption of any of these updated processes. Before the Ontario Judicial Council was created, complaints about judges went directly to the Attorney General. Dnieper was, several times, publicly upbraided by the Attorney General – but not dismissed from the bench. Dnieper threatened a 16-year-old with “the lash,” after the young man was charged with vagrancy in 1965. The charges against the young man had actually been dismissed but that didn’t deter Dnieper from delivering a very threatening lecture. The then-Attorney General, Arthur Wishart, in an interview with The Globe and Mail stated: “[T]his type of commentary and the way it was done and the language used does not add to the (good) impression of the public and does not please this court and does not please me.”[6] In the end, Dnieper far outlasted Wishart. Dnieper served 33 years on the bench until retirement in 1993.

Jack Batten’s account of Dnieper is reproduced below:

“The man appearing before Judge Robert Dnieper in the first week of October 1985 didn’t give off the feel of a student or a scholar. But, according to the evidence, he had in his possession 236 learned texts dealing with early Christian myths and history. The man’s name was George Elia, he was forty-eight years old and he’d stolen all 236 books from libraries at the University of Toronto. It wasn’t the first time Elia was caught swiping university books. He’d been nailed with a bag of texts in 1981, but since then he’d apparently gone in for thievery in a much more ambitious way. He’d enrolled in one non-credit course at the university, thereby acquiring a library card, and before librarians grabbed him in April 1985, he’d managed to squirrel away the 236 books which were worth about thirteen thousand dollars. Elia was hardly the only library thief in the university’s experience, just one of the most cagey, but as he stood before Judge Dnieper, he and the university knew that the other apprehended thieves had received nothing worse than a slap-on-the-wrist fine for their crimes.

Dnieper changed the old perceptions in a hurry.

“You have done incalculable harm to other students,” Dnieper said to Elia. “And this is going to be the first time in Ontario, and possibly all of Canada, that someone is going to jail for what you have done.”

He sentenced Elia to serve seven days in jail, put him on probation for three years, directed him to perform three hundred hours of community service, and ordered him to pay restitution for any of the 236 books that weren’t returned to the university.

That was Judge Dnieper on what most lawyers who appear regularly in his court would call a good day. On Dnieper’s other days, there’s no counting on his decisions or his sentences, his attitude to counsel or the quality of his repartee. Dnieper is the loose cannon among judges at Old City Hall. He is bright and quick but unpredictable; he has a sound knowledge of the law but might bypass it on occasions when he decides justice is best served by making an end run around the Criminal Code; he is fast with a genuinely witty line, the Johnny Carson of the Courtroom, but his humour sometimes takes on an edge that may be black or sexist or patronizing.

Many of his qualities went on vintage display one day in May 1983 in Twenty-three Court when Dnieper had before him an old-time rounder named Carroll who was pleading guilty to one count of theft under two hundred dollars. Mr. Carroll had light-fingered a couple of bottles of aftershave lotion and been caught in the act.

“How are you feeling?” Dnieper began with Carroll.

“Fine,” Carroll answered.

“How long do you want on this one?” Dnieper asked.

“You mean you want me to tell you how much I want?” Carroll said, slightly amazed.

“Yeah,” Dnieper said. “How long do you want in jail?”

At that point, the Crown Attorney, a woman named Goebbels, decided to put in her oar.

“Your honour,” she said, “this is his fifty-third conviction on theft. In January he got three months, and in March he got thirty days.”

“I don’t have time to read his record,” Dnieper said. “This court has to quit at five o’clock.”

Dnieper turned back to Carroll.

“Give me an answer,” he said. “How long do you want?”

“Ten days?” Carroll tried.

“Why not?” Dnieper said. “Sounds fair to me.”

Dnieper swung back to Ms. Goebbels.

“You see, crown,” he said. “Mr. Carroll is neither a plague of locusts nor a national disaster. He is an irritation much like a mosquito or a black-fly in June. It is a judgment of God upon our society and something with which we have to live. He is neither a danger to society nor a danger to the individual members thereof. He is merely a pain in the neck.”

“Yes, your honour,” Goebbels said, “but with respect, one usually tries to swat the black-flies or mosquitoes so they don’t come back again.”

“You and I must be thinking of different black-flies,” Dnieper answered. “Black-flies with which I’ve had anything to do defy swatting, and Carroll defies correction. So let’s accept him and forget about it.”

“Thank you, your honour,” Goebbels said, tossing in the towel.

But Dnieper wasn’t finished with Carroll.

“Listen,” Dnieper said to the man, “if I get you again, I’m going to throw you on the street without sending you up to the jail at all.”

Dnieper looked over at Ms. Goebbels.

“You see, crown,” he said, “the great value of the English common law is its ability to adapt to the situation.”

Dnieper has been either outraging or delighting his courtroom audiences since the day of his appointment to the bench in 1961. He is now in his mid-fifties, an imposing, forceful man… .

His hair is black and slicked back. His eyes are dark and constantly on the move in the courtroom. He checks out counsel, gives the accused a once-over, and scans the audience. He looks restless, like a judge who doesn’t mind a little controversy to juice up his day.

He may often be hard to read in his responses in court, but in a couple of areas Dnieper is utterly consistent. Drug offences make up one area. Dnieper is death on drug users and worse on drug pushers. Almost all Provincial Court judges grant a discharge to kids caught with a small amount of marijuana on a first offence, but Dnieper usually hands out a sentence. Defence counsel are aware of this propensity and try to steer clear of him when he is sitting in the drug courts. What they want to avoid, apart from a criminal record for their clients, is the lecture that Dnieper frequently delivers along with the sentence.

It’s The Dnieper Lecture to defence counsel. They know it by heart. It explains how the international commerce in drugs is related to the decline of the western world. Defence counsel are said to develop an automatic groan after too many exposures to The Lecture.

“The traffic in narcotics is an organized evil and a conspiratorial evil,” Dnieper began in the course of a typical five minute version of The Lecture during the sentencing in 1979 of a young man charged with the possession of marijuana. “In supporting these men who have no heart to our nation, the accused became one of them, an enemy to our people, and I do not view it lightly.”

And that wasn’t all.

“I won’t bore anyone with a recitation of the amount of Canadian dollars that flows outside the country for these drugs,” Dnieper went on. “All this, of course, has to be paid for by the sale of our natural resources.”

In the end, the young man’s penalty was comparatively light in Dnieper’s terms — a one-hundred-dollar fine or seven days in jail.

If Dnieper sounds like a patriot, he is. He emigrated to Canada from the Ukraine with his parents when he was a child, and though his early life was harsh – he was compelled to work in a factory as an eleven-year-old – he developed a love affair with his new home.

But his love does not necessarily extend to Canadian society’s dissenters and activists. A twenty-eight-year-old man named Scott Marsden discovered that truth when he appeared before Dnieper on June 24, 1985. Marsden had taken part in a sitdown in the driveway at Litton Systems, the Toronto company that makes parts for Cruise missiles. Marsden was arrested and found himself in front of Dnieper, who convicted him of mischief, bringing Marsden’s total to four mischief convictions during four demonstrations.

“The accused in the past has broken the law because he seeks to impose his will upon us all,” Dnieper rumbled. “The views of Canadian society are represented in the House of Commons, and the accused cannot contravene the will of the people.”

Then Dnieper hit Marsden with the toughest sentence for demonstrating that regulars around Old City Hall could recall.

Five days in jail, two hundred hours of community service, and prohibition from taking part in similar demonstrations for a year.

When something rouses Dnieper’s anger, he holds nothing back. He pitches into the case. An unfortunate pornographer came before him on February 22, 1985. The man was sixty-three- years old and the proprietor of a hole-in-the-wall store in downtown Toronto where he sold comic books over the counter. Under the counter, he peddled sex magazines which were imported from Europe and the United States. The magazines were long on violence and bondage, and their price tag was hefty, about thirty dollars per magazine. Dnieper studied the man’s product, pronounced it “disgusting,” and sentenced him to eighteen months in prison. The Crown Attorney on the case, John Hansbridge, felt his jaw drop in disbelief. “The usual penalty on such conviction,” Hansbridge said later, “is a fine and maybe a day in jail.” Not in Judge Dnieper’s court.

On the morning of October 16, 1985, sitting in Forty-two Court, Dnieper put on display another of the tendencies that set him apart from other Old City Hall judges — his blunt style of questioning. In a sense, his head-on directness is a reflection of his own quick mind. He can’t abide counsel who don’t get to the facts. Witnesses who dawdle over the case’s point drive him to exasperation. Dnieper has already absorbed the point while everybody else is still circling it. The difference in speed makes Dnieper twitch with impatience, and he was beginning to squirm in Forty-two Court on October 16 during a preliminary hearing on a first-degree-murder charge.

The accused was a Canadian Indian in his late twenties. Was wraith thin and wore a Fu Manchu arrangement of moustache and goatee and long black hair which was parted in the middle and fell around his shoulders. He sat unnervingly still in the prisoners’ box and gave off an aura of calm and peace.

According to the testimony of the crown witnesses, calm and peace may not have accurately described the Indian’s habitual state of mind. One of his former girlfriends had been murdered in a way that spoke of suffering and violation, and evidence pointed to the Indian as a certain suspect. The woman’s body had been found lying face down on the bed in her apartment. She was nude. Her hands were tied behind her back. Each of her buttocks showed a human bite mark. Her anus bore signs that something had been forced into it. And there were seven wounds on the back and sides of her head inflicted by blows from the traditional blunt instrument.

The police officers who investigated the case and the pathologist who performed the autopsy on the dead woman testified to the terrible facts of the killing with enormous restraint. They skirted around their descriptions of the body and its injuries, and the Crown Attorney needed dozens of questions to draw out their evidence. Each witness shied away from the horror of the events in the woman’s bedroom, and Dnieper wasn’t happy with the way the hearing was stretching through his morning. He shuffled the papers in front of him, chewed at the edges of his tie, and let out a couple of giant yawns.

The pathologist stood in the witness-box. He was presenting a list of the marks on the woman’s body — rope burns on the wrists, bites to the buttocks, injured anus, blows to the head — and he was taking his painful time about it.

Dnieper made his move. He’d accepted the testimony in edgy silence through the morning. Now he spoke up, addressing himself to the pathologist.

“Your observation is that the dead woman was subjected to bondage, sadism, sodomy, and murder?” he said in a swift tumble of words. “Is that about the size of it?”

The pathologist mouth dropped open. The Crown Attorney stood rigid at the counsel table. Everyone in the courtroom fell as still and quiet as the Indian in the prisoners’ box.

“Yes?” Dnieper said, still looking at the pathologist.

The courtroom turned instantly into a scene of purposeful action. The pathologist allowed that, yes, the judge’s description had summed up the situation. The Crown Attorney picked up the pace in his examinations. Witnesses grew crisp and authoritative. And fifteen minutes later, almost as an anti-climax, Dnieper wound up the hearing by ordering that, pending a decision on committal for trial, the Indian would be dispatched to the proper facilities, in custody, for a lengthy mental examination.

Court stood adjourned.

Judge Robert Dnieper had struck again.”[7]

- Batten, Jack. Judges (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1986) p.XIV. Reproduced with the permission of the author.↩

- Batten, Judges, p. 77.↩

- Enzo Di Matteo, Now, December 10-16, 1992 p. 10.↩

- Batten, Judges, pp.105-106, 109-111, 113-116.↩

- David Vanek, Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 1999) p.222.↩

- The Globe and Mail, June 16, 1965.↩

- Batten, Judges, pp. 97-104.↩

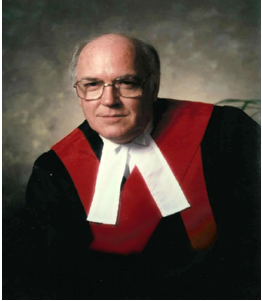

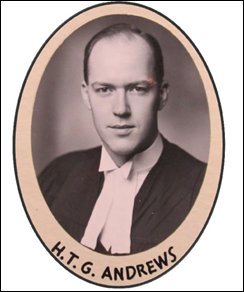

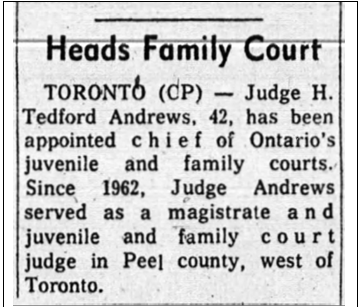

Ted Andrews: Getting Family Courts “Out of the Basement”

When Ted Andrews became a judge in 1962, he was dismayed to realize that the Juvenile and Family Courts were generally treated like “poor cousins”[1] of the Magistrates’ Courts that heard adult criminal cases.

He recognized the contribution Juvenile and Family Courts made to the community and justice system by resolving vital issues affecting families and children. Their work included cases concerning troubled youth (“juvenile delinquents”), children involved in the child welfare system, and orders for the financial support of spouses and children.

Symbolic of the problem was the fact that these important Courts, often poorly funded by municipalities and counties, were “forced to operate out of basements in public buildings or low rental spaces with back door entrances.”[2] As the first Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division), Ted Andrews was determined to bring them “out of the basement” both literally and figuratively.

“In Family Court, you have to

care as much for the people as

for the issues.”

Andrews served as Chief Judge for 22 years. Under his leadership, the Court created educational programming for family judges, worked closely with the community, and introduced innovations such as mediation. Andrews was a champion for the Unified Family Court – a court with jurisdiction to hear both federal and provincial family matters – and helped to launch the first “UFC” as a pilot project in Hamilton. He was later disappointed when young offender cases were removed from the UFC while other issues affecting children remained.

Andrews’ advocacy was not always appreciated by the provincial government which had assumed responsibility for the Family Courts in 1968. And his relationship with one Attorney General was particularly strained. However, throughout his long judicial career, Andrews was motivated by a desire to improve the lives and prospects of children and families that came before the Court. “In Family Court,” he said, “you have to care as much for the people as for the issues.”[3]

Early Life: Moving Around the Province

Harry Tedford Gee Andrews was born in the parsonage of John Street United Church in Sault Ste. Marie in 1927. His father was a minister and his mother played piano for the church choir. The minister’s work caused the family to move to Newmarket when Andrews was three, to Brampton when he was 11, and to Toronto during his teens. Andrews did not resent having been “shunted around” in his youth. He said it helped to build social awareness as he was constantly exposed to new people, experiences and communities. Times were tough during the Great Depression but Andrews recalled that, “we always had enough to eat, we dressed warmly, and we made our own entertainment.”

According to Andrews, his academic career began badly when he “flunked out of nursery school,” allegedly for eating a saucer full of glue which he had mistaken for maple syrup. At high school in Brampton, he pitched hardball and played football, hockey and lacrosse – much preferring sports to academics. Andrews had wanted to be a doctor, but after moving to Toronto he had a difficult adjustment when finishing high school at Vaughan Road Collegiate. He passed, but without the marks to get into medical school. Instead, he studied arts at Victoria College, University of Toronto.

The Lure of the Law

Andrews decided to go into law because Charlie Bowyer, the father of his good friend Blaine, was a lawyer back in Brampton. It never occurred to Andrews to follow in his own father’s

footsteps and become a clergyman. “I have always felt that you don’t have to be a church-goer to have an abiding faith and live by the principles in the Bible.”

Andrews began studying law at Osgoode Hall in 1949 at age 22. He paid for his education by working summers as a sleeping car conductor on the Canadian Pacific Railroad. Andrews was not initially enamoured with law school and had to write some supplementary exams. He took a year off to work at a large Bay Street practice, Sinclair, Goodenough. “At that time, a firm of 8 to 10 lawyers was considered big,” he would recall. There, Andrews was exposed to litigation when assigned to accompany lawyers to court where he took notes. At this turning point, he decided he “liked the law” and returned to Osgoode with renewed enthusiasm.

Andrews also became enthusiastic about Eva Karrys, whom he married in 1953. Eva was a psychologist who continued working until 1956 when the first of their two sons was born. Although neither son followed their father into the law, Andrews’ second wife, Judith Ryan, moved from a successful career as a social worker assisting children and families to become a well-known family law lawyer and mediator.

Back to Brampton

Andrews completed his articles in Toronto with two lawyers who shared office space on Bay Street. One had a family practice and the other worked in real estate. After being called to the bar, he returned to Brampton and joined Charlie Bowyer’s general practice. A year later, Bowyer’s son Blaine joined the firm. The four-person firm became Bowyer, Beattie and Andrews; it was 1954. Andrews was not interested in the fast pace of a downtown Toronto practice: “Quality of life was more important to me than the big bucks, even if the big bucks were available.”

Brampton was still a small community then, primarily serving a large surrounding farm district. Andrews estimated there were probably six law firms in practice at the time, including the firm of Albert Davis. Davis’ son Bill – the future Premier of Ontario – had been a year or two behind Andrews in high school in Brampton. As a young lawyer in Brampton, Andrews became involved in community work. “I was probably the youngest president that the Rotary Club ever had.” He also served as president of the local branch of the Victorian Order of Nurses and as an elder at St. Bartholomew’s Church. The women of the community convinced him to become president of the local Red Cross.