Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee

Justices of the Peace Advisory Committee

Conversion of Justices of the Peace

Part 1: Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee

Introduction: Appointment of Judges

A radical change to the judicial appointment process occurred in 1988 with the creation of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee (JAAC) – a non-partisan, arm’s-length body that evaluates and recommends candidates for appointment of judges to the provincial bench without political interference. The composition and reputation of the Court in the years since have been thoroughly transformed by the work of JAAC.

A History of Political Appointments

Historically, appointments to the provincial bench were often perceived to

be the result of political patronage – and while there is no doubt some appointees were eminently qualified, there is equally no doubt that political connections played an important role. This was especially true when magistrates could be appointed without any requirement of legal training or experience. In the Report of the Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights, Chief Justice McRuer made the following observation.

There has been a tradition in Ontario that there should be a strong political influence in the selection of magistrates…. There have been isolated cases where one who has not been a supporter of the party in power has been selected for the office, but such cases are unusual.[1]

Sharply critical of patronage appointments, McRuer was of the opinion that “[t]he appointment of a magistrate on the basis of political qualifications cannot be justified on any ground. It is not consistent with the elementary concepts of justice that one who has attained office merely by political service should have the right to preside over the liberty of the subject.”[2] At the same time, McRuer acknowledged that the process for appointing judges presented a challenge.

The task of selecting magistrates is an extremely difficult one and places a heavy responsibility on the Attorney General. There are no checks under our system such as the public hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee of the U.S.A., which reviews the nomination of federal judges for appointment. Such procedure provides some safeguards against unsuitable appointments, but it is not desirable that such a procedure should be followed here.

It has been suggested that the Attorney General should have a consultative committee of very responsible citizens to advise him on appointments. One of the advantages of such a committee would be to relieve him of political pressure.[3]

Screening Committee Versus Nominating Committee

There are two main forms a “consultative committee of very responsible citizens” might take: a screening committee, and a nominating committee. The difference between the two is the stage at which the committee assesses candidates.

- In the screening or review committee model, the Attorney General decides on the candidate and refers him or her to the committee. If the committee approves, the government proceeds with the appointment.

- In the nominating committee model, this process is essentially reversed. The committee conducts the initial assessment, and presents the government with a list of approved nominees from which to choose.

Although the screening committee process does provide some oversight, it still allows for considerable political influence. The government is unrestricted in its initial choices, and the screening committee only has the power to approve or disapprove the government’s nominee – not to assess whether he or she is the best qualified candidate among a pool of applicants.

With a nominating committee, the government is constrained and can usually only choose from among those who have been independently determined to be eligible candidates. The committee may be asked to consider all applicants and decide which are eligible for appointment, or it may have the power to select a small number deemed to be the best candidates; the government is then required to choose one of these – though it may have the power to go back to the committee if it feels none of the candidates would be suitable.[4] If the committee simply creates a long list of eligible candidates, the potential for politically influenced decisions remains; if it sends forward only those persons it considers the two or three best candidates, this possibility is essentially eliminated.

Judicial Council Role as a Screening Committee

Since 1968 – the year the McRuer Report was released – the Ontario Judicial Council had served as a screening committee for provincial court appointments, although its primary function was, and remains, to serve as a disciplinary body for provincial judges. The Attorney General would submit a list of names and the Judicial Council would provide advice and feedback on the individual nominees. The Judicial Council, composed of the Chief Justices and Chief Judges of all Ontario courts, members of the bar, and two non-lawyers, would generally be familiar with the nominees. It therefore typically relied on the personal, first-hand knowledge that its members had of each nominee, augmented by a meeting with the nominee, rather than conducting a formal review or information gathering process.

Margaret Campbell Joins the Bench in 1970

Margaret Campbell at her swearing-in ceremony shown shaking hands with Attorney General Allan Lawrence. At rear is Senior Judge V.L. Stewart; in front, Ontario Chief Justice Dalton Wells. (Photo: Getty Images).

Ted Andrews, former Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) recalled the 1970 appointment of Toronto politician, Margaret Campbell. After serving many years as a municipal councillor, Campbell ran as mayor of Toronto in 1969, placing second to William Dennison. She was “pushed at me just before a provincial election,” stated Andrews. He felt he had no reason to refuse her.Campbell and Attorney General Allan Lawrence, a Liberal, were pictured in the Toronto Star, shaking hands at Campbell’s swearing in ceremony in 1970. Campbell served on the bench for only two years, during which time Andrews found Campbell to be a “good judge,” but very difficult for him to get along with because of her strong views.

When Lawrence retired from politics, Campbell resigned her judgeship and ran as the Liberal candidate in Lawrence’s riding. She won the seat and served as an MPP until 1981. Margaret Campbell died in 1999.

(Source: Interview of T. Andrews for the Oral History Project of the Osgoode Historical Society, used with permission.)

1988: Introduction of the JAAC Pilot

In 1988, some 20 years following release of the McRuer Report, then-Attorney General Ian Scott announced the establishment of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee (JAAC) as a three-year pilot project. JAAC was conceived and implemented as a fully-fledged nominating committee. Its mandate was twofold: “First, to develop and recommend comprehensive, sound and useful criteria for selection of appointments to the judiciary, ensuring that the best candidates are considered; and second, to interview applicants selected by it or referred to it by the Attorney General and make recommendations.”[5]

Initially, the JAAC process operated as a supplement to, rather than in the place of review by the Judicial Council. This meant that Ontario had both an independent nominating committee – JAAC – and an independent screening committee – the Judicial Council – providing comments and making recommendations on candidates proposed by JAAC.

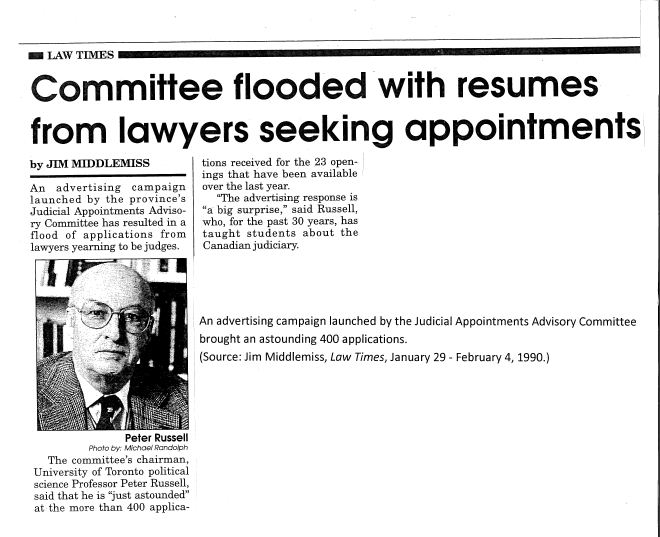

Peter Russell, a Professor of Political Science at the University of Toronto and first chair of JAAC, describes how he became involved.

Roy McMurtry and I had attended the University of Toronto together and remained good friends. I would occasionally have lunch with him when he was the Attorney General in Bill Davis’ government. I met him in his office one day, and just as we were about to go out he pointed to a whole bank of filing cabinets against a wall and said, “Do you know what is in there? Those are all files filled with information about candidates who want to be appointed to the Provincial Court. If you can figure out some way to improve this process I would love to hear about it.”

I was getting to the appointment of judges chapter in the book I was writing, and had researched the U.S. nomination processes aimed at taking the politics out of the system of electing judges. In Missouri, they had committees to consider and screen candidates and produce a list from which only one name would go to the voters. So the election wasn’t really an election; it was the confirmation of a selection by a professional nominating committee. I included the Missouri process in my book, The Judiciary in Canada, which was published in 1986.

By that point, Ian Scott was Attorney General. He was an equally good friend who had also been at U of T with me, and he called me up and said “I like what you say in your book about a nominating committee. Put your body where your pen is. Draw something up for Ontario.” So I did. There wasn’t much written about this at the time, but I read everything I could get my hands on, typed up a proposal, and sent it to Ian.[6]

The Members of JAAC

JAAC was a significant departure from the Judicial Council model – not only in terms of its mandate but also its membership. Unlike the members of the Judicial Council, the majority of JAAC members were neither lawyers nor judges. As originally constituted, the JAAC consisted of six non-lawyers, two lawyers, and a judge.

The non-lawyers were Russell, who chaired the committee, Valerie Kasurak, Michele Landsburg, David McCord, Robert Muir and Ben Sennik. Judge Robert Walmsley, the Associate Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) served as the judicial member, while Denise Korpan[7] and Clayton Ruby were the representatives of the bar. Ruby, a defence lawyer who had been appointed to the JAAC by the Law Society of Upper Canada, stepped down in February 1989 due to a concern that he appeared to show bias against Crown Attorneys. He was replaced by Tom Bastedo. In the autumn of 1989, Kay Sigurjonsson replaced Landsberg, who left to take up full-time duties at the Toronto Star, while a tenth member joined the JAAC, lawyer Donald Good.[8]

Finding Candidates

The JAAC’s first task was to plan its basic procedures, including how to advertise vacancies and how to assess and recommend applicants. One of the first decisions the JAAC made was to advertise vacancies in national and local newspapers as well as the Ontario Reports and Lawyers Weekly.[9] Vacancies on the bench had not been widely publicized previously; those who wished to apply relied largely on word of mouth. The response to the advertisements was remarkable.

The first advertisement generated 167 applicants and the number of applications grew steadily, reaching 452 in response to the fourth advertisement. Some of those applications were from individuals who had applied previously, but many were new candidates who told the JAAC that the advertisement “made them aware of the opportunity of being considered for judicial appointment even though they had no political connections.”[10]

JAAC took active steps to diversify the candidate pool, reaching out to “legal aid clinics, women’s organizations, Franco-Ontarians, West Indian and native lawyers’ associations.”[11] In addition, each advertisement stated that the committee was “seeking candidates who will reflect the diversity of Ontario’s people.”[12]

While the JAAC was at the time precluded from collecting information about applicants’ racial or ethnic background, it was able to determine that 12 per cent of the applications had been submitted by women. When JAAC was established, only four per cent of provincial judges were women. Before too long, that percentage increased dramatically.

Mr Speaker, I am pleased to be able to tell you today that we have appointed 18 new provincial court judges, and in the upcoming weeks I expect to appoint the remaining nine. The 27 appointments will help us to achieve a more representative provincial bench. Of the 18 appointments to date, 11 of these judges are women, including Canada’s first woman native Canadian judge.

Attorney General Howard Hampton, in a statement to the Ontario Legislature in March 1991, in the context of responding to court delays.[13]

Selection Criteria

JAAC developed selection criteria that stressed the importance of a diverse and representative judiciary. JAAC took the view that a representative judiciary was essential for two reasons: first, because the perspectives of various racial and ethnic groups, and of women as well as men, ought to influence how justice was administered and judicial discretion exercised; and second, because the judiciary appears more credible and inspires greater confidence when significant sections of the community do not appear to be excluded from its membership. JAAC was clear, however, that while it was seeking outstanding candidates from under-represented groups, a candidate from an under-represented group would not be recommended ahead of a candidate who was clearly better qualified although not from such a group.

The selection criteria also focused on professional excellence, community awareness, and personal characteristics. Professional excellence was the most obvious criterion, and the easiest to describe. Community awareness, on the other hand, proved more challenging to capture.

The Best and Worst of the Provincial Court

The JAAC was not alone in voicing concerns about judicial temperament and conduct on the bench.

In a survey conducted by Canadian Lawyer magazine in 1991, lawyers spoke about “uncontrollable ranting, bullying and arrogance” on the part of some members of the provincial bench.

Five judges identified as “the worst” of the Ontario provincial court were variously described as “petty, abusive, arrogant,” “arbitrary and capricious,” “a sexist, nasty, eccentric bully,” “cruel and inflexible with poor accused and young offenders,” and a “professional embarrassment.”

Those judges were criticized for treating litigants abusively, asking visible minorities if they spoke English, yelling at witnesses, delivering diatribes from the bench, and lacking compassion.

At the same time, the anonymous survey feedback about “the best” of the Ontario provincial court identified the personal characteristics that made judges trusted and effective: attentiveness, compassion, courage, courtesy, common sense, humour, and commitment to finding the right result.

The names of those singled out for praise were: William Sharpe, Brian Lennox, Mary Hogan, P.E.D. Baker, Sam Darragh, Brent Knazan, V.A.R. Lampkin, Donald MacMillan, H.D. Porter, H.A. Rice, John Smith, and Gérald Michel.

Source: Canadian Lawyer, March 1991, pp. 19-20.

Russell recalls that the committee was anxious to avoid defining community awareness as adherence to a particular viewpoint. “We wanted people not to be wedded to a particular position. We wanted people involved in the issues, both the pros and the cons.”

The community awareness criterion stressed a commitment to public service, interest in knowing more about the social problems that give rise to cases coming before the courts, and sensitivity to changes in social values relating to criminal and family matters.

Personal Characteristics

We watched some “not so good” judges performing, and oh my, that was an eye opener. What really struck us was the pomposity and rudeness and how off-putting that was. Someone would walk into the courtroom, the judge would look up, and the person would be shabbily dressed. The judge would say, “Who are you? You have no business here” and the person would slink out.[14]The “personal characteristics” requirement grew out of conversations with judges and JAAC’s own courtroom observations, as described by Russell.

The personal characteristics sought by JAAC included an “absence of pomposity and authoritarian tendencies,” “[r]espect for the essential dignity of all persons regardless of their circumstances,” “[p]oliteness and consideration for others,” “[m]oral courage,” and “[p]atience and an ability to listen.”[15] According to Russell, this was an area where the laypersons on the committee played “a pivotal role”: “They may not have legal training, but they are ‘very, very sensitive’ to the way the candidates carry themselves and help determine who is or isn’t personable.”[16]

Vetting Candidates

Once JAAC had established its criteria, it then had to apply them. It designed a personal information form to be filled out by each candidate, copies of which were then provided to all JAAC members. The members had on average 10 to 14 days to read through all of the applications for each round of vacancies, and each developed his or her own short list of candidates. The short lists would then be sent to the chair, and any name that appeared on two or more lists – that is, any candidate who had been identified as excellent by two or more committee members – would be given further consideration.

At this stage, the Attorney General would also be invited to review the combined list

and provide comments. JAAC members would then contact referees for each of the candidates on the combined list – typically 35 to 50 applicants. The members would also make discreet inquiries of judges and members of the bar whom they considered could furnish additional information on candidates’ qualifications. JAAC would then meet again to discuss the candidates and review the information provided by referees. Then they would agree on a short list of candidates to interview.

Ranked Lists of Candidates

After interviewing the candidates, JAAC would meet to determine its recommendations. One of the questions JAAC initially struggled with was whether to recommend a single candidate for each vacancy or provide a short list. According to its Interim Report in September, 1990, JAAC ultimately decided to provide a very short ranked list of applicants it considered best qualified for each vacancy.[17] JAAC took the view that if it were to submit just one name for each position, the Attorney General would be under great pressure to appoint that individual, and responsibility for judicial appointments would be too far removed from an accountable Minister.[18]

Although the ranked lists JAAC provided allowed for some Ministerial discretion, in all but one case in its first years as a pilot project the Attorney General appointed the person ranked highest by JAAC. The one exception occurred when the vacancy arose in Sault Ste. Marie, which serves an area with a significant Francophone population. None of the nominees on the list JAAC provided was Francophone or bilingual, and Attorney General Ian Scott asked if JAAC could recommend a strong bilingual candidate. JAAC conducted additional interviews and was able to recommend a fully bilingual lawyer with outstanding qualifications who was subsequently appointed.[19]

A Heady Experience: Getting JAAC Up and Running

The people involved at the beginning of JAAC were clearly excited about the prospect of a new and better way to select judges. The following are reminiscences provided by three of those involved – Michele Landsberg, Susan Dunn and Peter Russell – on the early days of JAAC.[20]

Michele Landsberg

Journalist Michele Landsberg was one of the lay (non-lawyer) members on the original JAAC.

I had just been back a year from New York and I got a call from Ian Scott, then the Attorney General in the Ontario government. As a life-long New Democrat, I wasn’t used to speaking to Liberals! He wanted me to be part of new process for choosing judges. I had been extremely critical in my articles in the Toronto Star about a predominantly male bench and rulings that were damaging to women. I was constantly attacking judges and their sexism. There was lots of material to fuel my indignation.

I was intrigued but sceptical about the new process for choosing judges. I was cynical about meeting with Ian Scott but he immediately won me over. “You mean this panel would be free to choose anyone who is qualified?” I asked. “Anyone – go far and wide,” he replied. I was floored and excited at the prospect that this would really be different. I agreed to serve.

Peter Russell convened our first meeting. He said we would invent an entirely new process: how we would find the candidates and how we would choose among them. At first, everything was contentious because we all had different viewpoints. Fortunately, the group came together quickly and well.

Ian Scott told us, “Give me a short list of three and I will choose from the three, guaranteed, I won’t go outside the three you propose.” That was a radical concept.

Traditionally, lawyers had applied through their MPP or local bar association to let it be known they wished to be appointed. That was so undemocratic. So many well qualified lawyers, particularly women and minorities, would not be part of the “in” group. So we decided to advertise. Some lawyers said, “How could you demean judges by advertising in the newspaper just like any other job!”

Then we decided to interview people face to face, though it was time consuming. We would reach out to find lawyers who would understand people in the community they would be serving. It was exciting and inspiring.

We decided early on that people given as references would obviously be favourable to the candidates. So we decided to do “discrete inquiries”. Confidentially, we would inquire with our contacts in the applicant’s community.

It was so onerous and we didn’t get paid a cent. Gradually, word spread and the applications came pouring in; we had to get lawyers’ briefcases on wheels to bring our documents to the meetings. And it was time-consuming to check phone references. But still, it was a heady experience. We felt privileged to be there and we took it very seriously.

We got really great people on the bench. It was an honour to help change the system.

Susan Dunn

Susan Dunn was a public servant assigned to work as JAAC’s first Committee Secretary.

It was life changing for me to work with this group of individuals who were leaders in their own communities and had so much life experience.

It was an enormous amount of work for all of us. Hundreds of applications would come in the door – we had bankers’ boxes full of application forms at the meetings. The judges checked the legal references and lay people did the community references.

Interviews were conducted by the full panel. I sat in on some interviews and was there when the Committee deliberated the first time. The meetings were long; some of them went from early in the morning to 11 o’clock at night. The first set of interviews went on for a few days straight. After the interviews were concluded, the Committee met to discuss each candidate and decide on the names to put forward to the Attorney General.

I always felt badly that this group of individuals never were paid. The per diem came along later. They were amazing individuals. They tried to recommend the best appointments they could. They worked tirelessly and worked well together. It was a highlight of my career to work with them.

Peter Russell

Peter Russell was the first chair of JAAC.

The Committee laboured over the three types of characteristics to look for in judicial candidates and what to look for in each one: professional, community and social awareness, and personal characteristics.

The list of personal characteristics came out of discussing with a number of judges, quietly, the characteristics of colleagues that worried them.

Community awareness skills was the most difficult to define. We didn’t want to define it as left of centre. We wanted people not to be wedded to a particular position. Take joint custody in family members, which was becoming a big deal for family law practitioners. We weren’t looking for people in favour of joint custody. We wanted people involved in the issues, and aware of the pros and cons. But if they hadn’t even heard of it, they wouldn’t do well with us.

Then we laboured over the process: how to advertise, how the committee would function, etc. We had no idea how many people would apply after we advertised. They just flooded in.

It was an issue to be doing this as volunteers because it started to eat up mountains of time. I had a wooden filing cabinet beside my desk and it was entirely JAAC, full of applications at various stages of processing.

It was a big job because we all pretty much read all applications, and then we had to agree as a committee who was the best.

We had a lot of fun – we had a good mix of people who really hit it off. We realized we were pioneering something that would be good for the country and the province.

Controversy: Role of Judicial Council

Controversy arose during the pilot project when, on several occasions, candidates recommended for appointment by JAAC were not approved by the Judicial Council. The Attorney General declined to appoint anyone about whom the Judicial Council commented negatively, so some of the candidates who were highly ranked by JAAC were passed over. In its Final Report on the pilot project, JAAC indicated it had “great difficulty accepting the Judicial Council’s rejection of its recommended candidates on substantive grounds”.

The Judicial Council does not issue reasons for its rejections, nor has it publicly stated its criteria. These criteria appear to differ, at least in part, from those of the committee. From what committee members have been able to gather through informal conversations, the Council often insists on relevant courtroom experience and attaches little value to professional experience outside of conventional legal practice as a preparation for judicial service. This is the committee’s best guess as to why candidates highly regarded by the committee and selected by the Attorney General have been turned down by the Judicial Council.

It is distressing to the committee that candidates who are selected according to its published criteria are later assessed by another body applying different criteria. The committee’s criteria were developed through public consultation in the first part of its mandate. They have been frequently published and a full explanation of them is contained in the Interim Report. These criteria, while placing a high value on a great deal of relevant courtroom experience, do not insist on it. The committee also attaches value to professional experience outside of a normal legal office in social agencies and policy development. In the opinion of this committee, it is unwise for Ontario to continue with two bodies screening and giving advice on judicial appointments. Whatever body performs this role should be accountable for its activities. Its procedures and its criteria should be known to the public.[21]

JAAC recommended that the Ontario Judicial Council should no longer have a role in the judicial appointments process, and that JAAC should be the only recommending body.[22]

A Permanent Body

Soon after taking office in the fall of 1990, Attorney General Howard Hampton informed JAAC that the government intended to introduce legislation to establish JAAC on a permanent basis. Amendments to the Courts of Justice Act, passed in 1994 and proclaimed on February 28, 1995, made JAAC permanent – and the only independent body involved in the provincial court judicial appointment process. A compromise was struck by including a member of the Judicial Council, appointed by that body, on JAAC,[23] although the majority of JAAC members – seven of 13 – continue to be laypersons. The importance of the composition of the committee as a whole reflecting Ontario’s linguistic duality and the diversity of its population, and of ensuring overall gender balance, are recognized in the selection of both lawyers and laypersons to serve on JAAC.

Standing the Test of Time

JAAC’s policies and procedures have stood the test of time, changing little over the years since it was first instituted as a pilot project. The criteria for appointment have been restated slightly, but the substance of professional excellence, community awareness, and personal characteristics remains the same. JAAC continues to advertise vacancies through both general publications and giving notice to more than 200 legal and non-legal associations, and encourages applications from members of equality-seeking groups.

Another Controversy: Standoff with Government

Since it became a permanent body, JAAC has encountered only one major controversy: in 1999 finding itself at loggerheads with the Conservative government led by Premier Mike Harris. Its shortlist of candidates to fill a judicial vacancy in North Bay did not include a Conservative Party loyalist and friend of the Premier. An article at the time by Globe and Mail justice reporter Kirk Makin outlines the details.

Ontario Premier Mike Harris’s home town has become the scene of a remarkable standoff that has left many judicial positions vacant and that legal officials fear is jeopardizing the 10-year-old practice of keeping politics off the bench.

At issue is a process created in 1989 to remove political patronage from judicial appointments. Operating at arm’s length from the government, the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee examines all judicial applicants and forwards a list of the top candidates to the Attorney General.

In the past, the Attorney-General has always announced the winning candidate within two to four weeks. The government has been sitting on the committee’s list of a half-dozen highly qualified lawyers for the North Bay position since June.

Judges and lawyers trace the delay in North Bay back to a name the government wanted to see on the short list: [a lawyer who is] a friend of the premier.

The number of judicial appointments in the province has recently dropped off dramatically, and many in the legal community say that the government provoked a standoff as part of a plan to wrest control of the selection process quietly.

Many judges and lawyers fear that the impasse signals a tug of war behind the scenes over the extent to which the government can control the naming of potential judges.[24]

The impasse between the Harris government and JAAC was of grave concern not only because of the apparent re-politicization of the judicial appointment process, but also because of the delays that were occurring while the vacancy went unfilled.

The inexplicable delay [in making an appointment] has created such grave backlogs that accused criminals may soon be winning acquittals on constitutional grounds, the chief judge in the region warned yesterday.

“It is a great concern to everybody,” said Regional Chief Justice G.E. Michel, who is responsible for a territory that covers the northeast of the province.

“I just don’t have enough judges to send a judge into North Bay on a regular basis,” Judge Michel said. “North Bay is falling progressively behind. Before long, this could create a very undesirable situation.”[25]

Government Backs Down

Faced with considerable public attention and political pressure, the government backed down and made appointments from the short lists JAAC had submitted. Since then, there has been no further attempt by any provincial government to interfere with the judicial appointment process, and JAAC has maintained its reputation for independence and transparency. In a 2015 interview with The Globe and Mail, William Trudell, chair of the Canadian Council of Criminal Defence Lawyers, described his five years as a member of JAAC as “probably one of the most remarkable experiences of my life. There was no politics in that room.”[26]

Contrast with the Federal Appointments Process

In 2015, controversies surrounding federal appointments have cast the benefits of the JAAC process in particularly sharp relief. Under the federal process, an eight-person vetting committee in each region considers written applications and designates each candidate as either “recommended” or “not recommended”. The vetting committee does not interview or rank candidates, thus leaving the government with considerable leeway to choose from among the scores of candidates on the “recommended” list.[27]

In a 2012 interview with The Globe and Mail, the chair of JAAC, Hanny Hassan, expressed the following with regard to the federal appointment process.

“When you include more people [on the list of candidates], it gives an attorney-general and cabinet a chance to make a political choice. …The smaller you make the list of candidates, the harder it is for someone who might be able to do the job but is not on par with some of the others, to get on it.”

While many federally appointed judges turn out to be fine choices, Mr. Hassan said, they are never able to shuck “the label of being a patronage appointment.”

Patronage also works to reduce the complement of minority judges who apply for federal judgeships, said Mr. Hassan, an engineer and former president of the Ontario Advisory Council on Multiculturalism and Citizenship. He said that potential candidates from aboriginal or visible-minority communities are deterred because they believe they will be unable to line up the powerful political connections.[28]

The article further noted that a recent survey by the newspaper found that 98 of 100 new judges appointed to federal courts in the provinces were white.[29] Between 2006 and 2014, only 30 per cent of federally appointed judges were women, compared to 44 percent of the judges appointed to the Ontario Court of Justice through the JAAC process between 2006 and 2012.[30]

The JAAC Approach Spreads

Through the 1990s and beyond, JAAC significantly increased the diversity and strength of the provincial court bench and, consequently, the esteem in which the Court is held – both by the parties who appear before it and by lawyers and judges across Ontario. But JAAC’s impact hasn’t stopped there. The JAAC model has also influenced how judges are appointed in provinces such as British Columbia, Alberta, and Nova Scotia – and as well in post-Apartheid South Africa. Peter Russell explains how this came to pass.

While JAAC was being implemented I was working on and off in South Africa. Canada provided a great deal of support to the post-Apartheid government in developing a new constitution. One of the questions the new government had to decide was how to appoint judges. I had a couple of colleagues who were part of the ANC, and we talked about the JAAC model.

They brought the idea forward: a neutral, non-partisan nominating process for all levels of court, including the Constitutional Court—the highest court in South Africa. They’ve taken the process further: when they interview their shortlisted candidates the interviews are public and the media are there. I’m not convinced that’s a good thing—I think there’s a great deal of value in confidentiality at the interview stage—but it’s wonderful to see how far the JAAC model has travelled, and how adaptable it’s proven to be.[31]

Conclusion: The Importance of JAAC

The Ontario Court bench has been transformed in three decades from one stocked largely with patronage appointees, to a very strong bench untainted by patronage.

Wayne MacKay, Professor of Law, Dalhousie University[32]

We are all the inheritors of a Court that has always contained a large number of excellent judges, working under conditions that we would never accept today, but our appointments are uniformly better than at any time in our history and are the envy of our colleagues in other courts.

Brian W. Lennox, former Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice[33]

The appointment process first announced in 1988 has proven to be one of the most important factors in transforming the Ontario Court of Justice to its present state. As of December 2012, 273 of the 284 – 96 per cent – of judges sitting on the provincial court had been selected through the JAAC process. The calibre and diversity of the judges sitting on the Court enable it to serve the public with distinction and to heighten the respect with which it is held by the legal community.

Part 2: Justices of the Peace Advisory Committee

Introduction: Appointment of Justices of the Peace

Chief Justice McRuer, in his 1968 report, was as critical of the appointments process for justices of the peace as he had been for magistrates and judges. He condemned the appointment of justices of the peace as a political reward and recommended all previous commissions be cancelled and that the province should start anew.

In 1981, Professor Alan Mewett reported to the Attorney General on the office and function of justices of the peace. He reiterated McRuer’s concerns, noting that nothing much had changed in the intervening years. Mewett emphasized the need to establish what it meant to be “qualified” to become a justice of the peace. “’Good character’ is clearly essential but this means ‘good’ in the social sense. (A justice of the peace) must be reasonably intelligent and appreciate his duties, capable of making independent decisions and able to act impartially and fairly.”[34]

Mewett went on to heartily criticize the “old-boy network” of appointing justices of the peace from “within the system – people with a pre-existing knowledge of court structure… this is not a desirable development. We should be looking for the best person available whether he is from within the system or not. A pre-existing familiarity with the system… should not, in itself, be any qualification for appointment.”[35]

Justices of the Peace Appointments Advisory Committee

While legislation in 1989 empowered the Justices of the Peace Review Council to consider all appointments, the reforms that were necessary to give real substance to these changes were not fully in place until the Access to Justice Act was passed in 2006.[36]

Minimum qualifications of a justice of the peace were prescribed by statute for the first time in 2006, specifying that those seeking appointment as a justice of the peace must have a university degree, comparable community college diploma or equivalent and 10 years’ experience in order to qualify.[37]

The 2006 legislation also established the Justices of the Peace Appointments Advisory Committee (JPAAC). JPAAC resembles the JAAC in many respects: its membership includes judges, justices of the peace, lawyers and lay persons. The criteria it has developed to evaluate applicants include interpersonal skills—such as courtesy, patience, moral courage, compassion, empathy and respect for the essential dignity of all persons—as well as decision-making, communication, and professional skills.

JPAAC differs from JAAC, however, it two important respects. First, it consists of both a core committee of seven members as well as seven regional committees, one for each of the regions of the Ontario Court of Justice. Second, rather than preparing a ranked short list of candidates as JAAC does, JPAAC classifies candidates as Not Qualified, Qualified, or Highly Qualified.

In this respect, JPAAC falls somewhere between the JAAC and the screening committees for federal judicial appointments. (The federal screening committees, following changes made in 2006, can only classify candidates as “recommended” or “not recommended.”) Although the absence of a short list leaves government with somewhat greater latitude in making justice of the peace appointments, the “highly recommended” classification means that JPAAC can still make its view of the relative merits of various candidates known.

Conclusion: The Importance of JPAAC

John Gerretsen, who served as Ontario’s Attorney General from 2011 to 2013 has summarized the improvements to the justice of the peace appointment process as follows. “We tightened up the process by only advertising positions in the various regions when vacancies occurred rather than advertising province wide twice a year regardless of whether or not there are any vacancies. While this is an improvement, the justice of the peace process still creates too large a list which may be subject to the potential of unwanted political influence. Although I was pleasantly surprised at the total lack of such influence during my term as Attorney General.”[38]

Newly Appointed Justices of the Peace, March 12, 2014

Left to right: Thomas Glassford, Rizwan Khan, Karen Valentine, Lloyd Phillipps, Rosann Giulietti, Karen Baum, Raffaella Scarpato, Paula Konstantinidis, Holly Charyna, Veruschka Fisher-Grant, Jane Hawtin, Ginette Forgues, Audrey Greene Summers, Jane Moffat, Anna Blauveldt, Renée Rerup, Andrew Clark (Senior Advisory Justice of the Peace), Kathy-Lou Johnson (Senior Justice of the Peace), Paul Langlois, J. Gary McMahon, Ralph Cotter, Michele Thompson, Faith Finnestad (Associate Chief Justice). Absent: Helena Cassano

In his 2014 decision concerning mandatory retirement of justices of the peace, Justice George Strathy (now Chief Justice of Ontario) commented upon the “judicialization” of the justice of the peace bench in recent years – and the improvements to the appointments process.

“The qualifications of the bench have been enhanced, the tenure of the justices (of the peace) has been made more secure and the processes and procedure surrounding the office have been made more professional, more formal and, in a word, more “judicial.” This evolution reflects the important role played by justices of the peace in the administration of justice in the province and the significance attached to that role by the legislature. It demonstrates a desire to attract highly qualified applicants to the position and to provide a structure, compatible with their judicial independence, to support the performance of their responsibilities.”[39]

- J.C. McRuer, J.C. Royal Commission into Civil Rights, Vol. 2 (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1968), p. 539. (“McRuer Report”).↩

- McRuer Report. McRuer further expressed, “On the other hand, no one should be excluded from an appointment because he [or she] has taken an interest in public affairs, either by reason of having held or stood for public office or having supported a particular party.” Indeed, McRuer himself had run, unsuccessfully, as the Liberal candidate for High Park in the 1935 federal election.↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, pp. 539-40.↩

- On the differences between screening and nominating committees, see F.L. Morton, “Judicial Appointments in Post-Charter Canada” in Kate Malleson and Peter H. Russell, ed., Appointing Judges In An Age of Judicial Power: Critical Perspectives from Around the World (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006), p. 69.↩

- Hansard, 15 December 1988, p. 6835.↩

- Interview with Peter Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Appointed to the Superior Court of Justice in 2012.↩

- Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee, Interim Report, September 1990, p. 5 (“Interim Report”).↩

- Interim Report, p. 10.↩

- Interim Report, p. 10.↩

- Interim Report, p. 10.↩

- Interim Report, p. 32.↩

- Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Official Reports of Debates (Hansard), 35 (26 March 1991) “Court System” (Hon. Howard Hampton).↩

- Interview with Peter Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Interim Report, p. 18.↩

- Jim Middlemiss, “Committee flooded with resumes from layers seeking appointments,” Law Times January 29 – February 4, 1990.↩

- Interim Report, p. 7↩

- Final Report, p. 17.↩

- Interim Report, p. 16; Interview with P. Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Source: Interviews of M. Landsberg, S. Dunn, P. Russell and H. Hampton for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Final Report, pp. 6-7.↩

- Final Report, p. 11↩

- Courts of Justice Act, s. 43(2)(d).↩

- Kirk Makin, “Judicial standoff creates controversy in Harris fold: Politics feared for delay in filling North Bay post,” The Globe and Mail, December 16, 1999.↩

- Makin, “Judicial standoff.”↩

- Sean Fine, “Legal observers urge Ottawa to revamp judicial appointment process,” The Globe and Mail, July 26, 2015.↩

- Kirk Makin, “Ontario system eliminates patronage in choosing judges, proponent says” The Globe and Mail, April 27, 2012.↩

- Makin, “Ontario system.”↩

- Makin, “Ontario system.”↩

- Stephen Lautens, “Cracking the system: How do we get more diversity on the bench when there’s no transparency in the appointments process?” Canadian Lawyer, September 2014.↩

- Interview with P. Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Makin, “Ontario system.”↩

- Brian W. Lennox, “Judicial Independence: Past, Present and Future – Judicial Independence and the Justice System,” Remarks to Central West Regional Meeting Judges, November 25, 2014, p. 5.↩

- Alan W. Mewett, Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on the Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario, Part 1, (“Mewett Report”), 1981, p. 68.↩

- Mewett Report, p. 68.↩

- Access to Justice Act, S.O. 2006, c. 21, schedule B, Amendments to the Justices of the Peace Act and the Public Authorities Protection Act.↩

- Access to Justice Act, 2006, s. 2.1 (15)-(17).↩

- Interview of J. Gerretsen for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario v. Ontario (Attorney General), 2008 CanLII 26258 (ON SC), para. 32.↩

Conversion of Justices of the Peace

The 1990s brought significant change to the governance and administration of the justice of the peace system – change that had been a long time coming and, according to many, was long overdue. “Conversion” was unquestionably the major initiative undertaken by the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) with regard to justices of the peace during this period.

It sounds simple. Conversion entailed eliminating “fee-for-service” reimbursement, thus making all justices of the peace in the province salaried. Another element was reducing five different categories of justices of the peace into two – “presiding” and “non-presiding.”

However, when the conversion process was started in 1988, it was immediately hampered by the fact that no one actually knew how many justices of the peace there were in Ontario. Some who were acting as justices of the peace had never been properly appointed. Others, whose names were on the rolls, were dead. A few had surpassed age 90. Some had never claimed fees. Others were collecting well over $100,000 a year in fees – often by cultivating an overly close relationship with local police.[1]

For years, alarms had been raised – in media articles and academic studies – about the disorganized state of the justice of the peace system.[2]

A System in Need of Clarification

Since the 1930s, justices of the peace had been under the “direction” of a magistrate and, subsequently, a Provincial Court judge.[3] But no one really knew what that meant – and those “directions” varied significantly from one county or district to the next.

In 1973, the Ontario Law Reform Commission summarized the situation this way: “The relationship of justices of the peace to the provincial judges and the Provincial Court system as a whole is a somewhat loose one and in urgent need of clarification.”[4] The Commission was highly critical of the fee-for-service system of paying justices of the peace: “The potential for abuse in a system which depends on justices of the peace remaining on good terms with the police in order to promote and maintain ‘business’ is obvious.”

In 1973, the process of bringing justices of the peace under the central control and supervision of the Chief Judges of the Provincial Courts (Criminal and Family Division) began.[5] This control was not firmly exercised, however.

Examining the Justice of the Peace System: The Mewett Report

In 1981, Professor Alan Mewett produced a landmark report on justices of the peace and their role in the justice system. Attorney General Roy McMurtry had commissioned the report following calls emphasizing the “urgent need to establish order and organization for the office.”[6]

In his report, Mewett characterized the justice of the peace system as “chaotic,” “hopelessly confused and unnecessarily complex”[7] and he detailed the specific flaws in the system. Work assignments were governed by a system of “directions” classifying justices of the peace into one of five designations which determined the functions each could undertake.[8]

The system of directions was hierarchical in nature. These ranged “from the limited one of receiving information relating to the commission of an alleged offence and issuing process thereon and adjourning cases in the absence of the trial judge, up through various stages to a justice (of the peace) with power to hear and determine various offences, to conduct bail hearings, to issues search warrants, to issues process and so on.”[9]

The “higher” directions assigning additional responsibilities were treated as a badge of prestige, and were often granted as a “kind of reward.” The system resulted in workloads that were irregular and uneven. This situation was reinforced by the fee-for-service remuneration practices – which Mewett considered “an invitation to a justice of the peace to abdicate his responsibility,” with the result that “some justices (of the peace) are perceived both by the police and the public as police justices of the peace while others pay for their rectitude by receiving little in the way of fees.”[10]

Despite the readily apparent disorganization plaguing this system, additional functions were being assigned to justices of the peace. For example, judges generally presided over bail and by-law courts until the 1970s. By the 1980s, those duties had been largely turned over to the justice of the peace bench.[11] The establishment of the Provincial Offences Court in 1979 had, in particular, substantially increased the responsibilities of the justices of the peace.

“Convenience Justices of the Peace”

“Convenience Justices of the Peace” were another example that the justice of the peace system, pre-conversion, suffered from a lack of governance – resulting in significant judicial independence concerns. Justice of the Peace Frank Devine recalled those days of “convenience justices of the peace.”

“Throughout the Province there were many court administrators or supervisors who were also appointed justices of the peace. Some referred to them as “convenience justices of the peace.” They did not carry out the normal duties of justices of the peace. However, if a judge had left the building without signing a warrant or committal document, they could sign for that judges as a justice of the peace. In some small jurisdictions, if a judge took sick, they could just remand cases until another date. The concern of course was judicial independence. These people were directly employed and worked under the direction of the Attorney General. Conversion solved the problem. Court administrators or supervisors were given a choice of giving up their justice of the peace commission or giving up their administration position and becoming a salaried justice of the peace.”

(Source: Interview of F. Devine for OCJ History Project, 2015.)

Streamlining the Administration of the Justice of the Peace System

Despite all these changes, the system was allowed to limp along in an administratively disorganized fashion until 1988, when Attorney General Ian Scott appointed Judge Gerald Lapkin to a new position with the title “Senior Judge, Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace,” having responsibility for the supervision and direction over sittings and assignments of justices of the peace.[12]

The members of the Office of the Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace in the early 1990s – during the “conversion process.” Back row, left to right: Rudy Buksbaum, Anatol Sywak, unknown, Inderpaul Chandhoke, Joan Romao. Middle row, left to right: Guillermo Lopez, Richard Le Sarge, Shelley Howell, Teen Huang. Front row, left to right: Kimberley Wahamma, Sonya Righi-Conlin, Rhonda Jeffrey. (Source: G. Lapkin).

Lapkin recalled embarking on the journey of locating each and every justice of the peace in Ontario.

The idea was to convert the fee-for-service system into a full-time, salaried, presiding justice of the peace system. The government wanted me to identify how this would happen. The first thing was to find out how many justices of the peace there were. There were very few records! We went back to order-in-council records from the 1920s. But we found some people who were acting as justices of the peace who never had an order-in-council. It took us over a year to identify what we felt was a list of most of the justices of the peace in the province – approximately 650. We sent out letters to everyone involved in the legal system – lawyers, police, court offices – to tell us of anyone they knew who was acting as a justice of the peace. We needed to know who there was, where they were, how old they were, and what services they were providing.

We spent approximately two years analyzing what we had and I realized there was no way you could convert the entire province to a system of full-time justices of the peace on one day…. We went region by region and the process was completely finished by 1998.”

The goal of conversion was to achieve professionalization of a bench that had been assigned increasingly expanded responsibilities. It was made clear to all justices of the peace that administration was being centralized – with explicit expectations established for sitting times and assignments.

As part of the conversion process, the decision was made to designate justices of the peace as either “presiding” or “non-presiding” on a full or part-time basis. All became salaried – no more fee-for-service arrangements.

The duties of a “non-presiding” justice of the peace include considering search warrant applications and presiding over bail hearings. A “presiding” justice of the peace has the same powers, with the added capacity to preside over a trial under the Provincial Offences Act.[13]

Maintaining Distance from Police

Kathleen Bryant became a justice of the peace in 1994. She watched as some of her experienced colleagues struggled to make the shift to a more independent and professional bench. For many years, they had enjoyed informal relationships with police and conservation officers. Simple things changed. No longer could they drop by the police station to share a coffee and shoot the breeze, for example.

(Source: Interview of K. Bryant for the OCJ History Project, 2013.)

Professionalization of the Bench

It was not enough to simply re-order governance of the system, however. According to Lapkin, to truly professionalize the bench other issues needed to be addressed. Instituting a formal education program for justices of the peace became a priority. In addition, the disciplinary and appointments processes were reviewed and refined to apply standards similar to those observed for the judges of the Court.

The justices of the peace themselves, recognizing that their status was being lifted by the conversion process,[14] began advocating through their associations with both the Ministry of the Attorney General and the Office of the Chief Judge for recognition in terms of increased remuneration. With the full support of the Office of the Chief Judge, the associations worked with the Ministry of the Attorney General to establish a remuneration commission in 1995.[15]

In the midst of the conversion process, the new position of Associate Chief Judge – Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace was created. In February 1995, Judge Marietta Roberts took on that role. She called the conversion process “unbelievable,” remembering her extensive travels around the province to swear-in justices of the peace to their new positions.[16] At each ceremony she would give a “pep” talk, detailing what was expected of the newly converted justices of the peace and the now-professionalized bench.

While the vast majority of the conversion process was completed by the late 1990s, it could be argued that “true” conversion was not achieved until 2006 when the Access to Justice Act was passed. This legislation introduced important provisions dealing with the designation of justices of the peace, their qualifications and the appointments process.

The inaugural group of Regional Senior Justices of the Peace. Back row, left to right: Ralph E. Faulkner, Ronald R. Griffiths, Patrick D. Daub. Front row, left to right: Anita C. Grassi-Blais, Carolyn A. Robson, Lynn Coulter, Carollyn A. Straughan, Opal M. Rosamond. Seated: Gerald S. Lapkin. (Source: G. Lapkin)

The 2006 statute abandoned the presiding/non-presiding distinction; today, all appointments are full-time presiding justices of the peace. The pre-2006 appointments were “grandfathered,” with four non-presiding justices of the peace remaining as of September 2015. The 2006 legislation also set out minimum qualifications for those seeking a justice of the peace appointment.

The Results of Conversion

By 2008, 20 years after “conversion” was completed, the office of justice of the peace was assayed by Justice George Strathy (as he then was; now he is Chief Justice of Ontario) in Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario v. Ontario (Attorney General) as follows.[17]

…the qualifications of the bench have been enhanced, the tenure of the justices has been made more secure and the processes and procedures surrounding the office have been made more professional, more formal and, in a word, more “judicial.” This evolution reflects the important role played by justices of the peace in the administration of justice in the province and the significance attached to that role by the legislature. It shows a desire to attract highly qualified applicants to the position and to provide a structure, compatible with their judicial independence, to support the performance of their responsibilities.[18]

- Interview of G. Lapkin for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- See for example: Warson, Albert. “The JP’s awesome power,” The Globe Magazine, February 1, 1966; Mewett, Alan W., Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on the Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario, Part 1, (“Mewett Report”), 1981; OLRC Ontario Law Reform Commission, Report on Administration of Ontario Courts, Part II, Ministry of the Attorney General, 1973.↩

- See for example: Justices of the Peace Act, S.O. 1936, c. 33, s. 2.↩

- Ontario Law Reform Commission, Report on Administration of Ontario Courts, Part II, Ministry of the Attorney General, 1973, p.17. (“OLRC Report”)↩

- Justices of the Peace Act, S.O. 1973, c. 149, s. 6.↩

- OLRC Report, p. 16.↩

- Mewett Report, p. 14.↩

- Jamie Cameron, “A Context of Justice: Ontario’s Justices of the Peace – From the Mewett Report to the Present,” Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy, Research Paper No. 44/2013, p. 7.↩

- Mewett Report, p. 12.↩

- Mewett Report, p. 23, Cameron, “A Context of Justice,” pp. 7-8.↩

- Interviews of F. Devine for OCJ History Project, 2014-15.↩

- This position was statutorily recognized in 1989 in An Act to revise the Justices of the Peace Act, S.O. 1989, c. 46 which came into effect in 1990.↩

- An Act to revise the Justices of the Peace Act, S.O. 1989, c. 46. ↩

- Until merged in 2000, two associations represented justices of the peace: Justices of the Peace Association of Metropolitan Toronto and the Justices of the Peace Association. The merged body is known as the Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario (AJPO).↩

- Letter from Senior Judge G.S. Lapkin to His Worship Frank Devine, President, Justices of the Peace Association of Metropolitan Toronto, June 2, 1992.↩

- Interview of M. Roberts for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- 2008 CanLII 26258 (ON SC).↩

- 2008 CanLII 26258 (ON SC), para. 32.↩