Introduction

Diversity on the Court

The Early Years (1867 to 1967): A White Man's World

The Provincial Courts Era (1968 to 1989): Native Justices of the Peace

A Consolidated Court (1990 to 1999): Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee

2000 - 2015 : Keeping Track

2015 - 2024: New Development in Diversity Issues

Different Pictures

Introduction

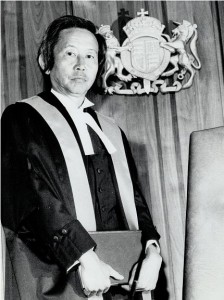

On a Friday in the 1970s, an Ontario family court judge received a threatening phone call from aman of Asian descent who had appeared before him. Because the caller was known to be violent, the judge was assigned 24-hour police protection. On Monday morning, a police officer followed the judge into the court house parking lot. Observing an Asian man getting out of a nearby car, the officer slammed him up against the car. The “suspect” was actually family court judge Kechin Wang. “Such a gentle sweet man,” recalled Ted Andrews, who was then Chief Judge of Ontario’s Provincial Court (Family Division). “It was shocking for him to be rousted like that.”[1]

The incident with Judge Wang took place at a time when judges were predominantly white men. It must not have occurred to the police officer that the individual might be a judge heading into work. Much has changed since then.

This essay examines the changing face of the Ontario Court of Justice. It considers ways in which the Court has – or has not – become more diverse, how the changes came about, and what the impact has been.

A Note on Terminology

One of the challenges in writing about diversity is deciding what terms to use when describing different groups of people. The literature refers to “women judges” so we use that term in this essay, but we do not refer to “men judges” because no one seems to use that term. When referring to statistical data, we use the terminology of the organization that holds the data in question. So we say “visible minority” when referring to data kept by the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee and “racialized group” for data provided by the Law Society of Upper Canada. We refer to the Court’s data on “native” justices of the peace and the Committee’s data on the appointment of “First Nations” judges. And of course, all quotes from interviews and newspaper articles contain the language used by the author. All of this has resulted in inconsistencies in the terminology used in this essay, which we acknowledge, but we have chosen to be faithful to our sources. We also recognize that terminology can be a minefield. An appropriate term today can be viewed as inappropriate – or even offensive, sexist or racist – tomorrow. We apologize if any terms in this essay make readers uncomfortable.

Diversity on the Court

What do We Mean by “Diversity”?

A diverse court is one whose judges and justices of the peace come from different backgrounds and life experiences, duly reflecting the population being served.

A diverse court includes women and men; persons with and without disabilities; persons of different sexual orientations; Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals; Anglophones, Francophones, and other linguistic groups; and individuals from a variety of racial, cultural and religious backgrounds.

Diversity is not, however, limited to the inclusion of judges and justices of the peace from specific populations or social identities. It can refer to any sense in which people bring a variety of perspectives to the court, including the kind of work they did before their appointments. Justices of the peace, who are not required to be lawyers, come from a wide range of occupations. They include former teachers, real estate agents, nurses, journalists, court clerks, social workers, and many more.

In a study of sentencing practices by Ontario magistrates, John Hogarth wrote: “Age, religion, education, social class background, and previous employment experience all were shown to have a relationship to magistrates’ behaviour on the bench.”[2]

Donald McLeod

Donald McLeod grew up in Toronto public housing with his mother and sister. He was appointed to the Ontario Court of Justice in Brampton in 2013.

“The law obligates me to look at the personal circumstances of each person who comes in front of me,” McLeod explained for an article about his story in The Globe and Mail.

“My background doesn’t help me to make the decision. At times it may help me to understand the individual.”

(Sources: “From the projects, for the projects”, by Sean Fine, The Globe and Mail, July 5, 2014; Ministry of the Attorney General News Bulletin, September 23, 2013.)

Why is Diversity Important?

Justice Maria Linhares de Sousa’s appointment as a Provincial Court judge in 1989 received media attention in Ottawa because she was a woman and an immigrant, having come to Canada from Portugal as a child. Linhares De Sousa later became a Superior Court judge when a Unified Family Court was established in Ottawa. She has described the importance of diversity from the perspective of the people who appear before the court.

For people coming before the court, diversity makes a real difference. A court should be representative of the people because it is the people’s court. The court should be something they can identify with—a place where they feel that they can be heard and understood. If the court is not diverse, people feel it is not part of them. A court could easily be rendered irrelevant as an institution if the bench is not representative of the population. Great care must be taken in selecting judicial officials.[3]

The importance of diversity among judges is often explained in terms of public trust, judicial impartiality, and the legitimacy of the court. Many authors, including former Supreme Court of Canada Justice Bertha Wilson, have cited the following statement.

But the ultimate justification for deliberately seeking judges of both sexes and all colors and backgrounds is to keep the public’s trust. The public must perceive its judges as fair, impartial and representative of the diversity of those who are being judged.[4]

This rationale was echoed by the Diversity Institute of Ryerson University when releasing the findings of its 2012 study on diversity among federally and provincially appointed judges in Ontario.

Judges are extremely powerful. Judicial impartiality and independence is a cornerstone of democracy. So is representation. The public trust and perceived legitimacy of the court depends on it.[5]

Judicial diversity is seen as something that can enhance impartiality and decision making. This does not mean that individual judges will be more impartial due to their backgrounds. It means that the court as a whole will be more open to different perspectives rather than viewing the world from a single vantage point. As expressed by Justice Maryka Omatsu of the Ontario Court of Justice, “[a] one-sided homogeneity of the judiciary cannot help but carry with it a narrowness of vision and of life experiences that is bound to create unconscious biases.”[6]

In a similar vein, American academic Sherrilyn A. Ifill wrote that “racial diversity on the bench also encourages judicial impartiality, by ensuring that a single set of values or views do not dominate judicial decision-making.”[7]

Rosalie Abella became a judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) in 1976 and, following a series of other appointments, joined the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004. She wrote that “[e]very decision maker who walks into a courtroom to hear a case is armed not only with relevant legal texts, but with a set of values, experiences and assumptions that are thoroughly embedded.”[8]

Having a broadly representative court does not guarantee that individual litigants will have judges who share their background or life experiences. However, the more varied the values, experiences and assumptions within the court as a whole, the more the court will be – and will be seen to be – open to the realities of the diverse public that appears before it.

“I recognize the value of having a different cultural perspective than many of my colleagues,” said Justice Manjusha Pawagi of the Ontario Court of Justice. “My cultural lens doesn’t take away the need to examine carefully, as all judges must, how my personal background and experience can affect the way I see the cases that come before me. The challenge for all of us is to use cultural sensitivity and avoid cultural bias”.[9]

A diverse court is an inclusive court. Just as the public should expect a fair and impartial hearing, there must be a fair judicial selection process that is open and accessible to qualified people from a variety of backgrounds. In 1990, Ontario’s newly created Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee captured the essence of why diversity matters:

The committee believes the judiciary will better serve the community if, in a sociological sense, it is reasonably representative of that community. The committee believes this for two reasons.

First, it is important that the perspectives of the various racial and ethnic groups that make up Ontario society, and the outlook and experience of women as well as men should influence how justice is administered. Judges have a great deal of discretion in interpreting and applying the law. In the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division), this is particularly true with regard to sentencing and the resolution of family problems. This discretion will be exercised more effectively and fairly when the judiciary is not dominated by a single race, or ethnic group or gender.

Second, the judiciary is likely to be more credible when significant sections of the community do not appear to be excluded from its membership. Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division) exercise great powers; they can impose years of imprisonment on a citizen and authorize the removal of children from the custody of their parents. Those who are subject to such decisions are likely to have more confidence in their fairness when they see members of their own social group appointed to the court that makes them.[10]

The Early Years (1867 to 1967): A White Man’s World

A great Judge must also be a great man.

John Buchan – A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, 1962[11]

Ontario’s early magistrates, judges and justices of the peace were almost exclusively white men. There were a few exceptions, of course.

- In 1908, William Peyton Hubbard became a justice of the peace for the County of York. Hubbard, the son of freed slaves from Virginia, had been Toronto’s first black alderman before becoming York’s first black justice of the peace.

- In 1922, Margaret Patterson, a white physician, became Ontario’s first female magistrate and presided over the Toronto Women’s Police Court.

-

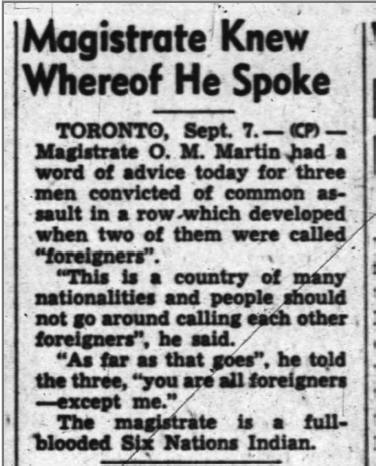

O.M. Martin, an Aboriginal man, was an Ontario magistrate in the 1940s and 1950s. Martin was elected president of the Magistrates’ Association in 1956.[12]

In 1955, Daisy Graydon, the widow of a deceased member of parliament, became a family court judge in the County of Peel.

Despite these historic appointments, the provincial bench remained predominantly white and male for many years. When Ted Andrews replaced Mrs. Graydon in 1962, he observed that women judges were a rarity.[13]

That same year, S. Tupper Bigelow published A Manual for Ontario Magistrates. The presumption that judging was exclusively a male profession is evident throughout the text: magistrates are consistently referred to as “he.” There can be no mistake about the gender of the intended audience when reading the quotations Bigelow included to illustrate the attributes of a good judge.

John Buchan: A great Judge must also be a great man.[14]

Justice Bernard Botein: There is a modern version of Lord Chancellor Lyndhurst’s definition of a good Judge: “First he must be honest. Second, he must possess a reasonable amount of industry. Third, he must have courage. Fourth, he must be a gentleman. And then, if he has some knowledge of law, it will help.”[15]

Bigelow’s manual, written for an audience of male magistrates, contains assumptions about women who appear in criminal court, whether as an accused person or as a witness. Back in the 1960s, Bigelow’s views were probably not considered to be exceptional or objectionable within legal circles.

It sometimes happens that an accused person conducts himself in an obstreperous or violent manner. This is much more often true of women than men.[16]

If a woman lies about her age, it is wholly probable that that is the only thing she ever lies about. Once a magistrate hears counsel ask a female witness: “How old are you?” he should say to the witness: “You don’t have to answer that question, Mrs. Smith.”[17]

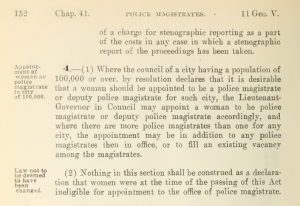

The Police Magistrates Act: Women on the Bench

In 1920, Magistrate George Taylor Denison announced that he would be retiring. The Toronto Local Council of Women and others lobbied for legislation to enable a woman to be appointed as his replacement on the Toronto Women’s Police Court.[18] There was nothing in the Police Magistrates Act to prohibit the appointment of women, but the view at the time was that the statute should be modified to address the issue before such an extraordinary step was taken.

The Act was amended in 1921 to specify that women could be appointed as police magistrates, but only in cities with populations of 100,000 or more and only where a resolution of the municipal council declared it was desirable for a woman to be appointed.[19] This paved the way for the appointment of Margaret Patterson as Ontario’s first woman magistrate in 1922.

The decision to amend the Police Magistrates Act was probably wise. Five years earlier, on Emily Murphy’s first day as an Alberta magistrate in 1916, a lawyer challenged her authority on the basis that women were not considered to be “persons” under the British North America Act (Canada’s Constitution). The next year, the Supreme Court of Alberta ruled that women were persons, but that concept was not decided for Canada as a whole until the famous 1929 “Persons Case” which went all the way to the Privy Council in England.[20]

The special provisions for female magistrates remained in Ontario’s Magistrates Act until 1952.

The Provincial Courts Era (1968-1989): Native Justices of the Peace

By 1968, transformation was underway in response to the Royal Commission Inquiry Into Civil Rights conducted by Chief Justice James McRuer. In December of that year, legislation was proclaimed to create the Provincial Courts, with a Family Division (to replace the Juvenile and Family Courts) and a Criminal Division (to replace the Magistrates’ Courts).[21]

The Provincial Courts structure remained in place for over 20 years. During that period, a notable change in the composition of the court came about as a result of the Ontario Native Justice of the Peace Program.

The Native Justice of the Peace Program

A report by law professor Alan Mewett to the Attorney General in the early 1980s marked a turning point in Ontario’s approach to justices of the peace. Among other things, Mewett recommended that “steps be taken to ensure the appointment of more justices of the peace for native reserve communities.”[22]

Confidence by the native people themselves in our criminal justice system will not be achieved unless they see native peoples dispensing not other people’s justice but their own justice. They must be part of the system, not subjects of the system, and if this requires reconciling Indian morals and ways of life with those of the larger community, then it will require trained, dedicated native justices of the peace, who have the necessary support, to achieve this. In the abstract, therefore, I have no hesitation in saying that there must be considerably more native persons appointed as justices of the peace for reserves and local native communities.[23]

Mewett’s vision included a training program to qualify native candidates for justice of the peace appointments.[24] Chief Judge Fred Hayes – known for a deep respect for native traditions and elders – embraced this vision and set out to create the Native Justice of the Peace Program. Staff from the Ministry of the Attorney General worked closely with local communities and northern Ontario Judge Gérald Michel to make it happen.

A feature of the program was intensive, pre-appointment training for candidates who might otherwise have been considered to lack qualifications necessary for appointment as a justice of the peace.

“Status Indian first native JP for Ontario.”

This headline appeared in The Globe and Mail on June 21, 1985. The article was about Charley Fisher, a status Indian member of the Islington Band.

Fisher had just been appointed as a full-time justice of the peace after having served on part-time basis for several years.

Fisher was quoted: “I hardly completed grade 8 education, buit I have learned a lot about court procedures.”

Judge Michel described the intent of the program as follows.

The aim was to have Aboriginal people working in the courts so they could feel part of the system in which they were so frequently involved, and to better serve the justice system in the isolated communities where people had no one to turn to for private complaints and the police had no one to go to for the issuance of process.

The aim was also to train justices of the peace who would preside over minor offences under the reserve band by-laws and to hear other provincial regulatory offences. It was expected that these justices of the peace would better administer the law in these communities where the culture was different from white man’s culture and not always understood by non-Aboriginal people.[25]

Michel recalled the challenges in recruiting applicants who feared their families would be ostracized if they assumed enforcement roles in the community.[26]

Opinions on the program were diametrically opposed. They ranged from “The best program that all justices of the peace should have to go through” to “It discriminated against native justices of the peace.” However all agreed that it was a very demanding program.[27]

Although the Native Justice of the Peace program continued for many years after it began in 1985, eventually the pre-selection education was eliminated. Nonetheless, the program’s impact has been significant in providing access to justice for Aboriginal communities, and access to judicial positions for members of those communities.

Now if we have a vacancy for a bilingual or First Nations justice of the peace, we advertise and carry on like any other advertisement. We have designated positions but sometimes we move them around for greatest need. In the northeast we have full time native justices of the peace in North Bay, Sudbury and Timmins.[28]

Four Women Judges and Counting

In his memoir, David Vanek wrote about being appointed as a magistrate in 1968, just a few months before the creation of the Provincial Courts. Vanek recalled, “Automatically I joined a select brotherhood of the judiciary. It was indeed a fraternal organization because not a woman graced the dais at this time or for several years thereafter.”[29]

In December 1968, the Ontario Gazette listed the individuals appointed to be Provincial Judges in the new Provincial Courts. Based on the names in that list, only four were women: Margaret Moncrieff Chambers, Marjorie May Hamilton, Mary Catherine Maloney, and Bertha Esther Thompson. These women were all family court judges.

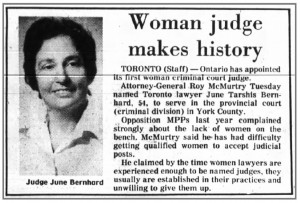

It was not until 1979 that history was made with the appointment of June Bernhard, the first woman to become a judge in criminal court, serving with Vanek and the “brotherhood” in the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).

Author Jack Batten made the following observations about Judge Bernhard in his book, Judges, published in 1986.

She specialized in civil litigation and built a career as a hard-working, astute counsel who didn’t miss a legitimate trick in court. In all her years at the bar, she took only a single criminal case….Bernhard never entirely believed she’d be named to the bench, not even when the big call came at seven o’clock one night in the spring of 1979.

“I’m the Deputy Attorney General,” the voice on the phone said. “And I’m the Shah of Iran,” Bernhard answered. She got the appointment anyway….

She was the judge whom you could spot in her office or over in the law library at Osgoode Hall at nine o’clock in the evening. “I prefer cases that have a little law to them and aren’t just a matter of assessing the facts,” she says. “The thing is that counsel often don’t direct you to the right law, which means you have to look it up for yourself. You have to research the decisions. Find the precedents. And that’s all right by me.”[30]

Mary Hogan was appointed in 1987 as a judge to hear criminal cases in Toronto’s Old City Hall, where Bernhard was the only other woman judge. Hogan was pregnant with her third child at the time. Attorney General Ian Scott had warned her that there was no maternity leave for judges. Hogan was out of the hospital on a Friday and back at work on Monday, with the baby. A secretary looked after the baby while Hogan presided in court. Later, Hogan and others were successful in getting maternity leave added to the list of judicial benefits.[31] New mothers on the bench had not been an issue when virtually all the judges were men.

Rosalie Silberman Abella: Appointed 1976

In 1976 there were only a few women serving as judges in the Provincial Court (Family Division) and none in Toronto. Chief Judge Ted Andrews wanted to help rectify the situation and deflect criticism about the lack of women judges available to hear family law matters. He called the family judges at the 311 Jarvis Street courthouse in Toronto and asked if they could recommend a “good woman candidate.”

Supreme Court of Canada)

Judge David Main recommended “Rosie” Abella, a young lawyer with a growing reputation in the local legal community. Andrews followed through and the Ontario government was prepared to appoint Abella to the Court. When Attorney General Roy McMurty eventually met with her, he was taken aback to see that she was several months pregnant. “Nobody told me about this,” he said. “Your appointment is going to cabinet next week. Do you still want the job?” She said yes and, at the age of twenty-nine, joined “the guys” at 311 Jarvis.

She sat in court until the day before giving birth. Afterwards, she stayed at home with the baby for two months, still receiving her judicial salary. When someone from the Ministry of the Attorney General called to say that there was no maternity leave program for judges and she would have to give the money back, she did.

Abella thrived as a Provincial Court judge. But there was also danger associated with the position due to angry parties in family law cases. “I had to deal with threats,” she said. “At one time my children had two bodyguards when they went to school.”

While sitting as a family judge, she retained a high profile in the community, speaking out on a variety of issues and, in 1984, serving as Commissioner of the federal Royal Commission on Equality in Employment. She resigned from the Court in 1988 when Ian Scott, newly named as Attorney General, said she could no longer serve as both a judge and as chair of the Ontario Labour Relations Board. She remained with the Board until 1989 when she became chair of the Ontario Law Reform Commission.

In 1992, Abella became a judge again, this time with the Ontario Court of Appeal. In 2004, she was appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. In reflecting back, she acknowledges the “group of remarkable family judges”–such as David Main, Patrick Gravely, Peter Nasmith, James Karswick, and Norris Weisman at the 311 Jarvis Street Provincial Court where she began her judicial career.

(Sources: Interview of R. Abella for the Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015; Biography of R. Abella on the Supreme Court of Canada website.)

George E. Carter: Appointed 1979

George E. Carter was born in Toronto in 1921. After graduating from the University of Toronto and a brief period of military service, Carter studied law at Osgoode Hall Law School. He articled with B. J. Spencer Pitt, known as the only black lawyer to be practising law in the province, and then practised real estate, criminal, and family law.

Attorney General Roy McMurtry was proud to appoint Carter as a Provincial Court judge in 1979. This made Carter the first Canadian-born black judge. Maurice Charles, born in Guyana, had been appointed to the provincial court several years earlier.

In the book Judges, Jack Batten provides the following sketch. “Judge George Carter is black and he’s massive in the manner of an old football linebacker who has let his weight find its natural limits….He was one of the few black lawyers in Toronto in the days when they were called Negroes. Carter practised by himself and took a shot at everything until he got his appointment to the Provincial Court.”

In January 2014, Carter became a member of the Order of Ontario, the province’s highest honour.

(Sources: Jack Batten, Judges (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1986), 88; websites of African American Registry, Ontario Ministry of Citizenship, Immigration and International Trade, Osgoode Hall Law School, University of Toronto, The Law Society of Upper Canada, (accessed January 2015)).

A Consolidated Court (1990-1999): Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee

A New Way of Selecting Judges

A pivotal moment in the changing face of the Court occurred with the creation of Ontario’s Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee by Attorney General Ian Scott. Helping to create a more representative bench was and has remained an explicitly stated goal of the committee. From the start, the committee aspired to identify judicial applicants with grassroots experience that qualified them above and beyond knowledge of the law.

Diversity was a high priority from the beginning.[32]

Susan Dunn, Secretary to first Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee

We would go far and wide to find lawyers who would understand people in the community they would be serving…[33] At the time, almost all the province’s 222 judges were men of Anglo-Saxon background; only 10 were women.[34]

Michele Landsberg, public member on first Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee

The advisory committee model – and its commitment to diversity – remains intact over 25 years later. In 2015, committee chair and community member Hanny Hassan said, “There is a political commitment that is also reflected in the Courts of Justice Act and in the advisory committee’s own published criteria: we expect to have a diverse bench.”[35]

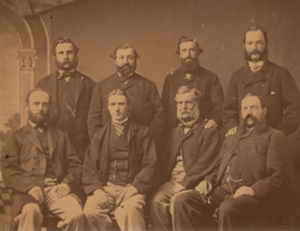

Front row, left to right: Denise Korpan, David McCord, Michele Landsberg, Valerie Kasurak. Back row, left to right: Robert Muir, Peter Russell (Chair), Susan Dunn (Secretary), Ben Sennik. Absent: Tom Bastedo, Judge Robert Walmsley. (Courtesy: Susan Dunn)

The Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee began as a pilot project in 1988 near the end of the Provincial Courts era. It became enshrined in legislation in 1995[36] when the Court was known as the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division). Ontario was the first jurisdiction in Canada to enact legislation of this type.

The committee was made up of public members (non-lawyers), lawyers and judges, with the majority – at Ian Scott’s insistence – being the public members.[37] After a process of advertising, interviews and reference checks, the committee would send its top candidates for judicial vacancies to the Attorney General. The government would then appoint a judge from the list.

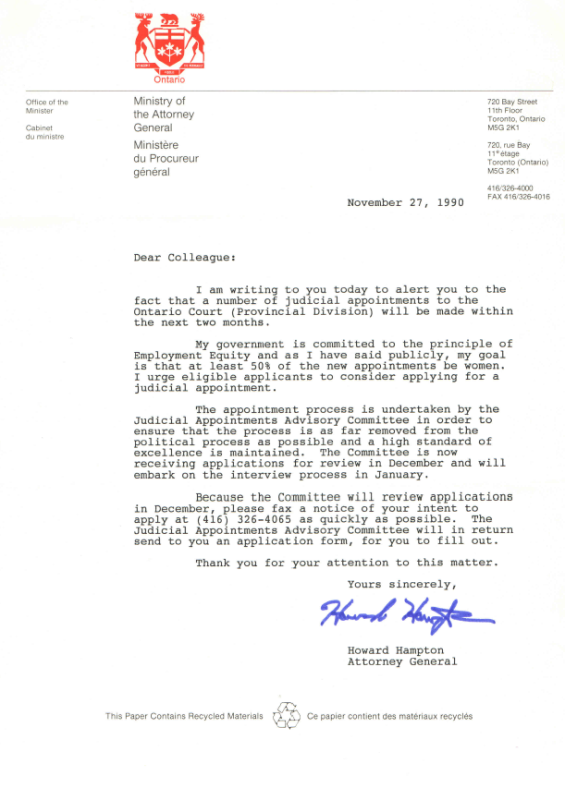

Encouraging Applications: The Hampton Letter

Advertising judicial vacancies – seen as a radical move at the time – was intended to produce a more diverse pool of qualified candidates. In the case of applications from women, the numbers spiked following active outreach in 1990 by Attorney General Howard Hampton of the newly elected New Democratic Party government.

Hampton was planning to appoint judges to help address court delays in light of the Askov decision[38]. In that decision, the Supreme Court of Canada defined a person’s right under the Charter to be tried within a reasonable time. As a result, there was a real risk of serious criminal cases being thrown out due to delays in bringing them to trial. Hampton wanted to ensure that 50% of the new appointees were women, and that racial minority, Aboriginal and Francophone judges were also appointed.

In November 1990, Hampton sent a letter to women who had been practising law for at least 10 years to encourage those eligible to apply for judicial positions. It worked. Due to the letter and the ads, the committee was flooded with applications from qualified women candidates. Many of them had previously thought it would not be “worth the bother” to apply without political connections.[39]

Hampton also made sure there was outreach to Aboriginal, Black and Francophone lawyers through their associations.[40]

In a statement to the Ontario Legislature in March 1991, Attorney General Hampton reported on his progress in the context of responding to court delays.[41]

Mr Speaker, I am pleased to be able to tell you today that we have appointed 18 new provincial court judges, and in the upcoming weeks I expect to appoint the remaining nine. The 27 appointments will help us to achieve a more representative provincial bench. Of the 18 appointments to date, 11 of these judges are women, including Canada’s first woman native Canadian judge.[42]

In November I wrote to some 1,200 women lawyers inviting them to apply to become judges. As a result, more than 40% of applications for the new positions on the provincial bench came from women, compared to 12% of applications in previous competitions. The trend in judicial appointments is clear: No longer will we hear the argument that there are not enough eligible women who want to become a judge.

Opposition member and future Attorney General Charles Harnick responded that hiring “francophones, racial minorities and women” is “all very good and it is all very proper.” However, he worried that the criterion of ability “has gone out the window.”[43]

Active outreach to achieve judicial diversity continued through the 1990s and beyond. In 1997, Justice Maryka Omatsu made the following observation.

Social commentators have long remarked on the ties between the judiciary, business, and the major political parties. Now there is also an increasing adverse popular response in a pluralistic society to a powerful, tenured institution that is overwhelmingly white, male, and upper-middle class.

In this climate, governments are moving towards greater representation on the bench, in recognition that increasing public respect for the law requires a judiciary that is more reflective, aware and sensitive to the people and issues before the court.[44]

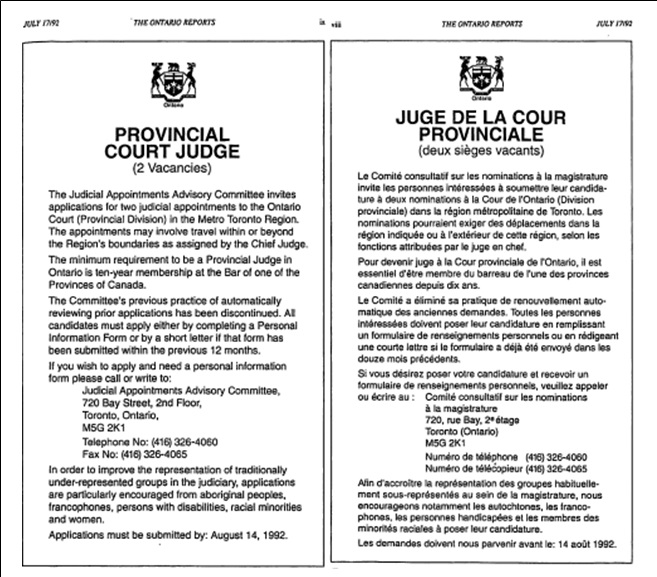

Omatsu, the first woman of East Asian origin to become a judge in Canada, applied to become a judge after reading a notice that changed her life. The notice – in the July 17, 1992 edition of the Ontario Reports – encouraged “traditionally under-represented groups in the judiciary” to apply for two provincial judicial vacancies.[45]

Backlash: “I Want to Be a Judge But I Don’t Wear a Skirt!”

Not everyone was pleased with the growing diversity of judicial appointments or the push for more women to become judges. This was especially true among white, male, politically connected lawyers who thought that it was “their turn.” Peter Russell, the first chair of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Council, recalled the following incident.

I got a call pretty early, maybe in the second or third year, from a male lawyer. He said he was pretty disgusted: “I want to be a judge but I don’t wear a skirt!” I controlled my temper. I said, “Yes, we have recommended a number of women. But please do me a favour. If you find out from your own experience before these women judges or from your colleagues in the profession that they are not up to scratch, I want to know. I won’t disclose you as my source. We want to be doing good work here.” He said, “It’s a deal,” but he never called me back![46]

In the 1970s, when affirmative action helped to place women and racial and ethnic minorities on federal courts in the United States, another type of backlash occurred as defendants “began challenging their minority judges for bias.”[47] A similar phenomenon occurred in the mid-1990s as Ontario’s administrative tribunals became more diverse. For example, women adjudicators were challenged for bias in sexual discrimination and harassment cases due to their feminist backgrounds.[48] Fortunately, the Ontario Court of Justice did not experience this type of backlash as the new appointment process began to increase the diversity of that Court.[49]

Harvey Brownstone: Appointed 1995

Harvey Brownstone was born in France and raised in Hamilton, Ontario. When Attorney General Marion Boyd appointed him as a judge of the Ontario Court of Justice in 1995, he became the first openly gay judge in Canada.

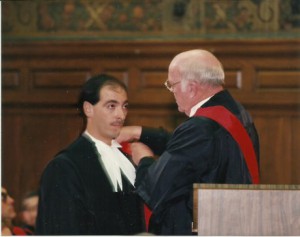

Swearing-in ceremony of Justice Harvey Brownstone, robed by former Chief Judge Ted Andrews, 1995.

As Boyd has said, “Harvey was openly gay but there were others appointed before him who were not comfortable about being open in their sexual orientation.”

In 2011, Brownstone achieved another “first” as a judge when he began hosting a television show to educate the public about family law matters. This followed from his bestselling book Tug of War: A Judge’s Verdict on Separation, Custody Battles, and the Bitter Realities of Family Court. The book, also aimed at the general public, includes a foreword by Ted Andrews who had served for many years as Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division).

(Sources: Interviews of M. Boyd and H. Brownstone for OCJ History Project, 2014 and 2015; The Globe and Mail, “Ontario judge’s showmanship leads to TV series,” Kirk Makin, Sept. 7, 2011. Photo courtesy: H. Brownstone.)

A Welcoming Environment for All?

It must have been difficult for Maurice Charles to be the only black judge when he was appointed in 1969 and for June Bernhard – the only woman criminal court judge – when she was appointed 10 years later. To encourage and maintain a diverse court, it is important that the environment is welcoming of diversity. This can benefit all people who find themselves in an Ontario courthouse, whether as a judicial official, court staff, legal professional, or member of the public.

In 1993, a public report from an inquiry into allegations of a judge’s conduct put a spotlight on the need for a safe and harassment-free environment for women working in the Ontario Court of Justice, whether as judges, justices of the peace, or administrative staff.

This inquiry…is not concerned with Judge Hryciuk’s ability or performance as a judge in the courtroom. The evidence is unchallenged, that over his career he has been not just a good judge but an excellent judge in that respect. What is in question is Judge Hryciuk’s conduct in relation to women when he is not engaged in his specific judicial function.[50]

This was not the first or only report that found a male judge or justice of the peace to have engaged in inappropriate sexual comments or actions. Even though the Court of Appeal later quashed the Commissioner’s findings and recommendation[51], the report had a major impact on personnel within the court system. It led to more comprehensive gender sensitivity training for judges of the Court and greater involvement of women in delivering such programs.

2000 and Beyond: Keeping Track

In the best of all possible worlds, those holding public office would, by the simple law of averages, tend to reflect the same ratio as the general ethnic make-up of society – if, that is, social, economic and cultural backgrounds were such as to provide equal educational, employment and economic opportunities for all members of society. We do not live in that Utopian society yet, though perhaps one day we will.

Alan Mewett, 1982[52]

Since 1995, the Ontario Court of Justice has kept statistics on the gender, bilingual status, and age of its judges. It later began to do the same for justices of the peace, and also to track the number of native justices of the peace. The Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee reports statistics about appointments from representative groups. What can we learn from the numbers?

The Justice of the Peace Bench is More Diverse

Almost 20 years after a committee began to select judges in a radically different way, the government amended the Justices of the Peace Act to create the Justices of the Peace Appointments Advisory Committee. From its creation in 2007, this regionally based committee has operated on similar principles to those of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee. The legislation recognizes “the desirability of reflecting the diversity of Ontario’s population in appointments of justices of the peace.”[53]

Even without a longstanding committee, Ontario’s justice of the peace bench has become more diverse than the bench of judges. For example, the Court’s statistics show a higher percentage of female justices of the peace than female judges: 47% versus 32% as of January 2015. Of the Court’s 398 justices of the peace, 187 were women as of January 2015.

| Justices of the Peace Ontario Court of Justice |

|||||||||

| Full Time | Per Diem[54] | Total justices | Male | Female | Bilingual | Average age | Average age at appointment | Native justices | |

| Jan 2015 | 328 | 70 | 398 | 53% | 47% | 11.1% | 62 | 47 | 7.3% |

| Judges Ontario Court of Justice |

||||||||

| Full Time | Per Diem | Total judges | Male | Female | Bilingual | Average age | Average age at appointment | |

| Jan 1995 | 248 | 22 | 270 | 83.3% | 16.7% | 5.6% | 56 | 44 |

| Jan 2015 | 284 | 59 | 343 | 67.3% | 32.7% | 12.1% | 61 | 47 |

(Data Source: Statistics provided by the Office of the Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice, January 2015).

The justice of the peace selection process appears to place less emphasis than its judicial counterpart on outreach and tracking appointments from designated groups, with the exception of native justices of the peace. Nonetheless, the committee has recommended the appointment of many justices of the peace from diverse backgrounds. This may be a reflection of the diverse individuals who apply for positions, encouraged by an awareness of people like themselves actually holding these positions.[55] While statistics are not available on all types of diversity, the photograph of newly appointed justices of the peace at the end of this essay bears witness to the mix of women and men from different backgrounds being appointed to the justice of the peace bench.

The Percentage of Women Judges Continues to Rise

The most dramatic change during the first 20 years of data collection has been the increase in women judges: from 16.7% in 1995 to 32.7% in 2015. Thus, as of January 2015, 113 of the 343 judges on the Ontario Court of Justice were women.

In 1921, a legislative amendment had to be passed to allow for the appointment of Ontario’s first female magistrate. In 2015, women held all three of the top judicial leadership positions (Chief Justice and the two Associate Chief Justices). Times have certainly changed, at least with regard to women on the bench.

|

Sisters on the Court Holly Charyna, a former chief of the Temagami First Nation, was appointed in March 2014 as a Justice of the Peace in Owen Sound. Her sister, lawyer Catherine Mathias McDonald, was appointed the next month as a judge in Parry Sound. Both women were raised on Bear Island. Journalist John R. Hunt reported about this notable family in an article for the North Bay Nugget as follows.

|

(Sources: North Bay Nugget, “Judge, Justice of the Peace in the family”, by John R. Hunt, April 16, 2014 (reprinted with permission); Ministry of the Attorney General News Bulletins, March 4, and April 8, 2014. Photos courtesy: Bear Island Blast Newsletter, May 2014.)

There Has Been Progress in Appointing Aboriginal Justices of the Peace and Judges

When Terry Vyse was appointed as a judge of the Ontario Court of Justice in 1991, she became the first Aboriginal woman appointed as a judge in Canada. By 2012, Ontario had appointed six judges who had identified as belonging to a First Nation. This represented 1.9% of judges appointed through the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee process. According to Law Society of Upper Canada data from 2013, this percentage is similar to the 1.8% of Aboriginal lawyers who have been members of the bar for more than 10 and fewer than 20 years. Ten years at the bar is the minimum requirement for appointment as a judge of the Court. The 2013 data also indicate that Aboriginal people comprise 2.3% of the Ontario population[56].

In 2015, there were 29 native justices of peace, comprising 7.3% of that bench. This percentage is higher than that of judges who identified as First Nations and greater than the percentage of Aboriginal people in the overall population of the province.

Justice David Cole, who co-chaired the Commission on Systemic Racism in the Ontario Criminal Justice System, recalled an event from 1994.

During the Commission’s work, (Chief Judge) Sid Linden called me up and asked me to go to a conference of U.S. judges looking at race bias in American courts. Sid sent Judge Terry Vyse and me as the court’s representatives. We were the only non-Americans among the 1000 attendees. We knew going in that Terry was the first Aboriginal woman judge appointed in Canada. What we could not have known is that according to the Americans – and the attendees would be in a good position to know – there were at that time no known Aboriginal women judges in the entire US judiciary, excluding women in tribal courts[57].

Bilingual Capacity Has Risen Among Judges and Justices of the Peace

In criminal cases, people have the right to be tried in French if that is their choice. This right generally applies where the person’s language is French or where French is the official language in which they can best give testimony. In family and Provincial Offences Act cases, there is a right to bilingual court proceedings. Therefore, it is essential for the Ontario Court of Justice to have judges and justices of the peace who are able to hear cases in French[58].

The Court’s statistics show an increase in judges who are bilingual, rising from 5.6% in 1995 to 12.1% in 2015. This meant that 42 of the 343 full time and per diem judges were able to conduct hearings in English and French as of January 2015. Similarly, 11.1% of justices of the peace (44 of 398) were bilingual as of January 2015.

In 1990, when the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee was still a pilot project, its members were relieved to see that, with one exception, the Attorney General had selected the individuals most highly ranked by the committee:

The one exception occurred in unusual circumstances. Because none of the judges serving the particular region could conduct trials in French and there was a significant Francophone population in the area, the Attorney General was determined to appoint a fluently bilingual person to the position. He made this known to the community and to the committee. The committee’s first recommendation for this position did not have a fully bilingual person at the top of its list. The Attorney General decided not to appoint any of the persons on this list and asked the committee if it could recommend a strong bilingual candidate. The committee then submitted the name of a bilingual candidate who was highly ranked but when the Attorney General received negative comments on the individual from the Judicial Council, the appointment was not made. The committee then endeavoured to generate some additional applications from bilingual candidates. It interviewed several more candidates and eventually was able to recommend a fully bilingual lawyer with outstanding qualifications who was then appointed to the position[59].

It should be noted that a bilingual judge is not necessarily a person whose mother-tongue is French. As of December 2012, the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee reported that 7.1% of judges selected through its process were Francophone.

The Provincial Bench is More Racially Diverse than the Federal Bench

How can we determine if the Court has become more racially diverse since the 1970s incident involving Judge Kechin Wang? Several data sources can shed light on this question.

First, the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee reported that as of 2012, 23 judges who had identified as “visible minorities” had been appointed through its process, representing 7.1% of appointments.

| Appointments from Representative Groups | ||

| Total No. | Percent (N=322) | |

| Women | 117 | 36.3% |

| Francophone | 23 | 7.1% |

| First Nations | 6 | 1.9% |

| Visible Minority | 23 | 7.1% |

| Persons with Disabilities | 0 | 0% |

| (Source: 2012 Annual Report of Ontario, Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee. (As of April 2015, this was the most recent annual report available.)) |

Second, the Law Society data show that 19.1% of Ontario lawyers practising for 10 to 19 years, and 7.1% practising from 20 to 30 years, are from racialized groups[60] as compared to 16.9% in the community[61]. This is a clear indication that the pool of lawyers eligible to become judges is becoming more racially diverse.

Third, Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute has examined the representation of women and visible minorities in various levels of courts in Ontario. Their research found a notable variance between federally and provincially appointed judges in terms of visible minorities. In 2012, using a sample of 138 provincially appointed judges, Ryerson found that 10.9% were visible minorities, compared to 15% of practising lawyers in Ontario. By contrast, the study found that only 2.3% of federally appointed judges were from visible minorities. The Diversity Institute credits the provincial appointment process – in place since 1988 – for increasing this type of diversity within the Ontario Court of Justice.[62]

A picture of growing diversity can also be gleaned from the Law Society of Upper Canada’s “Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities.” Excerpts from the biographies appear in the appendix to this essay.

For its First 23 Years, the “JAAC” Process Resulted in No Appointments of Judges with Identified Disabilities

There have always been persons with disabilities on the Court. Examples include veterans who became magistrates and justices of the peace after returning from the Second World War. And they include judges such as James Lunney, who was close to legal blindness at the time of his appointment as a judge in North Bay in 1970. In some cases the disabilities were visible and known at the time of appointment. In others, the disabilities remained “invisible” or emerged years after appointment.

It is somewhat surprising that the annual reports of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee show zero appointments of judges with identified disabilities during its first twenty-three years of operation. Between 1989 and the end of 2012, 322 judges were appointed through the “JAAC” process. This included women (36.3%), Francophones (7.1%), First Nations (1.9%), and visible minorities (7%). By contrast, none of the 322 appointees were persons who had identified themselves as having a disability[63]. This may be due, in part, to the limited pool of applicants with disabilities among lawyers eligible to become judges, or to a lack of self-identification regarding certain disabilities during the selection process.[64]

Victoria Starr identified herself as having a disability when she applied for an appointment to the Ontario Court of Justice. In her application, she stated:

I am a person with a visual disability. Not once has my visual disability stopped me from being a strong and effective advocate and litigator or from making significant and meaningful contributions to both the non-legal community and legal profession. I do not see my visual disability as negatively affecting my ability to be a judge, but it will mean that I do some things differently from how other judges do them…I am very familiar with what’s out there in terms of low vision technology and aids, and I know how to use these tools effectively. Being a visually challenged judge will bring, as it should, a greater sense of and respect for the strength of vulnerability in our community[65].

Justice Starr, who had practised family and child protection law, became a judge of the Ontario Court of Justice in July, 2014, presiding in Milton. She has said, “One in nine people has some sort of disability. Having a legally blind judge is part of the Court’s evolution to create a more diverse and representative judiciary.”[66]

Despite some encouraging examples, the JAAC statistics are an indication that disability is an aspect of diversity that the judicial appointment process has not addressed. To do so would require more than simply appointing persons with disabilities. It requires efforts to prevent and remove barriers and to make arrangements (accommodation) that enable individuals to participate fully.

While the nature and extent of a disability could prevent a person from conducting certain judicial duties, many disabilities can be accommodated, especially with new advances in technology.

In the case of mobility challenges, the structure of courthouses is a major factor that affects access by the public, legal profession, court staff, judges and justices of the peace. In a brief to the 2014 review of Ontario’s disability legislation, advocates noted that “a number of good accessibility features were commendably included” in two new courthouses built after the passage of the Ontarians with Disabilities Act 2001 and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act. “Yet only 25% of the courtrooms in each of these two new buildings are equipped with an accessible judicial dais. For fully 75% of those courtrooms, a judge with a mobility disability cannot get up to the judge’s bench and preside.”[67]

| James Lunney: Appointed 1970 “Blindness is irrelevant to judging”

|

James Lunney was the regional solicitor for Ottawa-Carleton before being appointed as a provincial court judge in North Bay in 1970. He replaced Judge Gérald Michel, who switched from North Bay to Sudbury.

When Chief Judge Hayes recommended the appointment, Lunney had extremely poor vision from a hereditary condition. He was declared legally blind two years later. According to Michel, “Hayes knew he was blind and there were some concerns. But he also knew that he could practise with the disability and that he had a reputation as being very bright, so it was worth taking a chance.”

“Lunney did well on the bench despite his disability,” observed Michel. “He got others, including his wife Eleanore, to help with reading. The only restriction was that when he was doing out of town courts — Sturgeon and Mattawa, for example — he had to go by taxi, hampered by his inability to drive.”

It helped that Lunney had an excellent memory that enabled him to remember the evidence and the regulars who appeared in his courtroom. “Blindness is irrelevant to judging,” Lunney said. It also helped that, at the time, criminal cases were generally shorter and less complex than they later became, so there were fewer legal materials and transcripts for judges to read.

Lunney died in 2005 at the age of 79. An obituary reported that he was known around town as “the blind judge with the seeing-eye poodle.”

It might be hoped that Lunney would be seen as a trail blazer, paving the way for persons with disabilities to serve as provincially appointed judges. History has shown that this was not the case.

(Sources: Interview of G. Michel for OCJ History Project, 2015; Obituaries in North Bay Nugget and Ottawa Citizen; Toronto Star article, Jan. 15, 1994, “Poodle pioneer gives freedom to judge with failing sight.” Photo from Lunney obituary, Ottawa Citizen.)

Reasons for Different Levels of Diversity

Some authors have written about the “prestige theory.” This premise is that in certain countries (but probably not in Canada or the United States) women and minorities are most likely to be appointed to less prestigious courts[68]. Those who take a hierarchical view of the courts could make something of the fact that, when it comes to visible minorities, the federally appointed Superior Court bench in Ontario is less diverse than the provincially appointed bench[69], which in turn is less diverse than the justices of the peace bench.

In the case of provincially appointed judges, the face of the Court began changing dramatically (with the exception of persons with disabilities) after the introduction of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee in 1988. The even greater diversity of Ontario’s justices of the peace bench is interesting since its appointments advisory committee wasn’t introduced until almost 20 years after the judges’ committee was established. The fact that justices of the peace need not be lawyers, and can therefore be drawn from a larger population pool, is likely a significant factor.

Social Context Education

Judging is a significant act that requires careful attention, and respect for legal rules and principles. It is an act that requires qualities of humanity and compassion. Judging requires an effort to shed prejudice and untested beliefs[70].

Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C., Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada

Even a highly diverse court cannot guarantee that parties will be treated with sensitivity and understanding in relation to gender, race, disability and other issues, or that judicial bias and stereotyping will no longer exist. Since 2000, judicial education programs have encouraged judges to consider the social context of the cases before them, in addition to the factual and legal context. The goal is to promote equality and reduce unintended bias that can result from being unaware of social conditions and changes.

Deciding in accordance with the law, within reasonable time, and in accordance with the process mandated by law, is only one part of the judicial task. Justice must also be delivered in a responsive manner, one that takes account of the social context, and the different perspectives of those who seek it. Justice must also be delivered in an impartial manner, one which is free from prejudice or false assumptions about cultural difference. In a world marked by pluralism, in communities where diversity is so prevalent, the judge must become the interpreter of difference. The judge must become the one who understands every voice[71].

Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin, P.C., Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada

Initially, social context education was controversial with some members of the judiciary, but it has been welcomed by many as a way to further equality within a framework of judicial independence. In a 1997 decision, the Supreme Court of Canada formally recognized the importance of judges taking social context into account.[72]

2015- 2024: New Development in Diversity Issues

Introduction – Moving towards Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion[74]

During the term of Chief Justice Maisonneuve, the Ontario Court of Justice undertook a range of significant initiatives to address diversity and inclusion.

In part the Court was responding to societal initiatives and pressures, including the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Both national initiatives brought overdue attention to the impacts of colonization and the residential school system on Canada’s First Nations and Indigenous populations, including the overrepresentation of Indigenous persons in the criminal justice and child protection systems. In addition, the impact of the death of George Floyd and worldwide attention to the Black Lives Matter movement brought a renewed commitment to address the impact of anti-Black racism and the overrepresentation of Black Canadians in the criminal justice and child-protection systems.

The independence of the judiciary requires the Court to demonstrate sensitivity to the appropriate spheres of influence in addressing broad social, economic, and legal inequities. In order to respect the limited jurisdiction that the Court has, equity, diversity and inclusion initiatives were undertaken in the spheres of judicial education and court processes.

In reflecting on the diversity and inclusion initiatives undertaken from 2015 to 2023, it is important to acknowledge the important groundwork on a range of Indigenous initiatives that Associate Chief Justice Peter Griffiths and Chief Justice Bonkalo laid in their terms of office.

Working Group Report

In the spring of 2012, the Ontario Court of Justice and Ministry of the Attorney General

Joint Fly-In Court Working Group was established to examine the operations of the Ontario Court of Justice criminal and family fly-in courts held in First Nations communities in the Northwest and Northeast Regions. Northwest Regional Senior Justice Marc Bode and CSD Regional Director JoDee Kam were co-chairs of the Working Group.

The Working Group membership included the Deputy Grand Chief of Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) responsible for justice issues, representatives of NAN Legal Services, OCJ judiciary and staff, Ministry court services and prosecution officials, representatives of the defence and family bar in the regions, and the police services that work in these communities: Nishnawbe Aski Police Services (NAPS) and the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP). Members of the Working Group also received input from several Band Councils, the Ontario Native Women’s Association (ONWA), Legal Aid Ontario, Office of the Children’s Lawyer and the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services. While the Working Group focused on the operation of the OCJ court system in fly-in remote communities, the members were very aware of the serious systemic problems that affect these First Nations communities. These systemic problems present broader policy issues for the justice system to grapple with. These broader policy issues were also touched upon by the Honourable Frank Iacobucci in his Report on First Nations Representation on Ontario Juries[75].

The Working Group report[76] was sent to Chief Justice Bonkalo and Court Services Assistant Deputy Attorney General in August 2013. The Court and Court Services reviewed the recommendations and Northeast Regional Senior Justice Patrick Boucher and Northwest RSJ Joyce Elder (who had replaced RSJ Marc Bode) worked with affected justice system partners and First Nations to implement the recommendations in the following years. Sadly, more than in any other part of court operations, COVID-19 significantly disrupted the operations of Fly-In Courts and renewed efforts were required to address access to court services in fly-in communities.

Indigenous Peoples’ Courts Report

Chief Justice Bonkalo and Associate Chief Justice Griffiths were also responsible for initiating more focused judicial education on a range of Indigenous issues, including hosting an Urban Aboriginal judicial education program in May 2011 featuring a keynote address by The Honourable Mr. Justice Murray Sinclair, then of the Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench and Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (subsequently appointed to the Senate of Canada). The session focused on issues related to the law around Gladue principles,[77] restorative justice and the issues related to the developing number of Gladue courts, subsequently more commonly referred to as Indigenous Peoples Courts.

OCJ Gladue or Indigenous Peoples’ Courts have significantly evolved since 2001, when the first Gladue Court in Canada was initiated at Old City Hall by Justice Patrick A. Sheppard. Indigenous Peoples’ or Gladue Courts, are specialized courts that handle the cases of Indigenous persons who have been charged with a criminal offence. Indigenous Peoples’ Courts apply Canadian law (e.g., the Criminal Code and case law), but also include Indigenous cultural practices and Indigenous concepts of justice, such as restorative justice. These specialized courts focus on sentencing, and in some locations, also bail and case management. They do not handle trials or preliminary hearings. In 2024 there were 21 Gladue or Indigenous Peoples’ Courts operating in the Ontario Court of Justice. All Canadian courts are required to apply Gladue principles and relevant Criminal Code sentencing and bail principles regardless of whether a matter is heard in an Indigenous Peoples’ Court or a regular court.

In some court locations, even where there is no dedicated Gladue or Indigenous Peoples’ Courts, there may be additional court support services, including Indigenous Courtworkers or Gladue workers, available to assist accused persons and the Court.

In 2016 Chief Justice Maisonneuve and Associate Chief Justice Peter DeFreitas hosted an innovative judicial education Indigenous Issues Conference, developed in consultation with Justices Joseph Bovard, Sarah Cleghorn, Gethin Edward and Shaun Nakatsuru. Further details on the conference are available in the Education chapter.

The Conference was a catalyst for increased consciousness concerning Indigenous issues within the Court. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, from its establishment in 2008 to the final report in December 2015. raised the awareness of Canadians about the tragic impacts of colonization and the residential school system. In addition, from 2016 to 2019 the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls continued to raise the consciousness of Canadians on related issues and brought overdue attention to the overrepresentation of Indigenous women and girls among murdered and missing Canadians.

The conference featured a series of panels with a broad cross-representation from judiciary, justice system and community participants on various aspects of Gladue Court operations and principles as well as on crossover kids and the impacts of child protection. The conference included a keynote address by TRC Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild entitled Perspectives on Truth and Reconciliation: Taking up the Challenge of the Calls to Action.

Following the conference the Court reviewed a number of policies and practices related to the operation of Indigenous Peoples’ Courts, and respectful practices in all courts related to the appropriate use of Eagle feathers and other Indigenous ceremonial objects.

The Court also reviewed the long-standing Native Justice of the Peace Program,[78] with the insights and assistance of the Senior Justice of the Peace/Administrator of the Program, His Worship Marcel Donio.[79] The Program continues with annual seminars for justices of the peace who self-identify as Indigenous. In 2018 the Program title was changed to the Indigenous Justice of the Peace Program. At the same time, Her Worship Wendy Agnew, a proud member of Garden River First Nation, was appointed to replace His Worship Donio as Senior Indigenous Justice of the Peace.

In 2019 the Court formalized the establishment of an internal Indigenous Initiatives Advisory Committee (IIAC). The Committee’s formation recognized the spirit of reconciliation encouraged by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action and the Calls to Justice in the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The committee, initially chaired by the Associate Chief Justice and Coordinator of Justices of the Peace Sharon Nicklas before her appointment as Chief Justice, and as of 2023 by newly appointed ACJ Jeanine E. LeRoy, provides a forum for consultation on initiatives the Court is committed to undertake to address Indigenous issues, within the scope and jurisdiction of the judiciary.

Following the federal government’s legislation in June 2021 mandating a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation annually on September 30, the three Chief Justices of Ontario announced that most Ontario courts would be closed on September 30, 2021, to mark the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. This affected all OCJ criminal, family, and Provincial Offence Act matters. Weekend and Statutory Holiday (WASH) courts and courts required to address adjourned matters remained open.

This was a historic opportunity for the Ontario Courts to mark the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, to reflect on the shameful legacy of residential schools and to recognize the ongoing impact on Indigenous communities, including to honour survivors, families, and communities so deeply affected by the residential school system. The Courts have continued to be closed on subsequent National Days for Truth and Reconciliation.

In 2022 and 2023 the IIAC was instrumental in developing judicial education materials and sessions to assist the judiciary in reflecting on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and related issues significant to Indigenous communities in the province.

Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Report

In 2021, Chief Justice Maisonneuve also welcomed the appointment of a new Associate Chief Justice, Aston Hall. ACJ Hall is an experienced judicial leader, having served as a Local Administrative Judge in Scarborough, Regional Senior Judge in Toronto and a member of the Court’s Education Secretariat and Ontario’s Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee. Associate Chief Justice Hall was born in Kingston, Jamaica and brings his experience as an immigrant and a proud Black Canadian to serve as the Court’s first Black Associate Chief Justice. ACJ Hall’s replacement as Toronto Regional Senior Justice, Sandra Bacchus, is also Black. ACJ Hall has commented that he believes having Black judicial leaders in the Court is important and assists the people the Court serves in seeing greater diversity in Court leadership.[80]

In September of 2021, shortly after ACJ Hall assumed his new responsibilities, Chief Justice Maisonneuve launched the first internal Advisory Committee on Judicial Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, with a mandate to provide advice and recommendations to the Chief Justice. In launching the Committee, the Court recognized the importance of promoting a fair, accessible and efficient justice system. ACJ Hall, as the Committee’s Chair, brought renewed commitment and fresh insights to issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion. Like his predecessor, ACJ Peter DeFreitas, ACJ Hall also Chairs the Education Secretariat of the Court. Both ACJs have a deep commitment to the importance and potential of judicial education to address challenging diversity and inclusion issues in an open and sensitive fashion.

In 2021 the Court renewed its commitment to social justice issues in judicial education, including on issues of violence against women and girls, disability issues, LGBTQ2S, Indigenous issues and anti-racism.

The judicial education focus of the 2022 Annual General Meeting of the Court was on diversity, equity, and inclusion. Dr. Tanya (Toni) De Mello, Vice-President, Equity and Community Inclusion at Toronto Metropolitan University, and a human rights lawyer with a unique background in economics, finance and operational management, was the keynote presenter and session facilitator. Dr. De Mello engaged the judiciary in a day- long interactive exercise to examine their identities and the way that shapes their relationships and evaluative capacity. The session also examined gender and racial bias and how bias can affect the ways people hear and interpret evidence, and the way in which parties are evaluated in the courtroom. ACJ Hall noted[81] that he was incredibly proud of the standing ovation Dr. De Mello received at the conclusion of the session.

ACJ Hall has also expressed pride[82] that the Court’s demonstrated leadership and creativity in addressing these issues in judicial education have received national recognition.

In February 2023 and 2024 exceptionally well-received educational videos were developed for Black History Month with the input of the Advisory Committee on Judicial Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion and shared with the judiciary, as part of the renewed focus in judicial education on Black History and Anti-Black Racism.

In May 2023, Chief Justice Maisonneuve commented,[83] as her term as Chief Justice concluded, that the collaboration received from members of the bench in addressing the important issues of equity, diversity and inclusion and responding to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations had been impressive. Maisonneuve further noted that given the judiciary’s limited jurisdiction, she believed the focus on judicial education was both logical and important. While noting the significant successes, such as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Black History Month education sessions and resources, CJ Maisonneuve acknowledged the need to continually review and move forward to address the needs of the bench and the diverse populations who come before the Court.

The conclusion to this updated version of the Court’s history will read in a similar fashion to that of the years that precede it. Judicial education for the judges and justices of the peace is not in any way static. It continues to mature, based on many different factors, to reflect the needs of those the Court serves.

Different Pictures

There has been progress in terms of a more reflective bench as law students change and work their way through the system. When I finished law school in Ottawa in 1977, I was the only black person there. Now we see outstanding candidates in almost every composition of the group making it to the interview process. But it is still not where it needs to be.

Hugh Fraser, Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee member and Regional Senior Justice, Ontario Court of Justice[73]

The judges and justices of the peace of the Ontario Court of Justice are no longer a predominantly white male group – the status quo that had prevailed until as recently as the 1980s. To some extent, this parallels what was happening in other sectors as societal attitudes became more open to the inclusion of women and minority groups in leadership positions. But has the Court become truly representative of the population and has its diversity made a difference?

The Court is not, and never could be, a perfect mirror of Ontario’s population. Nor can we expect all types of diversity to be measured, given the variety of backgrounds people bring to the Court in addition to being members of specific demographic groups. Still, the data collected by the Court and others can shed light on where progress has – and has not – occurred.

The most dramatic progress, as of January 2015, has been with native justices of the peace and with women (as justices of the peace and judges). While there has also been progress with Francophones and some groups of visible minorities, there is still a distance to go, particularly when it comes to the appointment of persons with disabilities. In the case of judges, diversity can be expected to increase as the eligible pool of Ontario lawyers becomes more diverse.

My personal experience has been that the appointment of a diverse bench has been of real benefit in a number of different ways, many of them intangible.

Brian Lennox, Former Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice

There have been growing pains and some backlash generated along the way. But for the most part, the Ontario Court of Justice has evolved into a more diverse court, more so in some respects than courts comprised of federally appointed judges. The extent to which the Court’s diversity has improved overall impartiality and decision making is difficult to assess. It is fair to assume, however, that diversity has helped to avoid unconscious biases that likely were present in earlier times when the bench was much more homogeneous than it is today.

- Interview of T. Andrews for OCJ History Project, 2014; Transcript of T. Andrews’ oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1995 (used with permission).↩

- Hogarth, John. Sentencing as a Human Process (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972), p. 388.↩

- Interview of M. Linhares de Sousa for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- As quoted in Scott, J.E. “Women on the Illinois State Court Bench” (1986) 74 Ill B.J. p. 436 at p. 438; as cited by Wilson, Bertha. “Will Women Judges Really Make a Difference?” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 28.3 (1990): 507-522 at p. 518. ↩

- Diversity Institute, Ryerson University, Media Release, “Research from Ryerson University Finds Increased Representation of Women in Canada’s Judiciary, but Visible Minorities Left Behind,” June 27, 2012, quote from Wendy Cukier. ↩

- Omatsu, Maryka. “The Fiction of Judicial Impartiality,” 9 Can. J. Women & L. 1 (1997), p. 16. ↩

- Ifill, Sherrilyn A. Racial Diversity on the Bench: Beyond Role Models and Public Confidence, 57 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 405 (2000), p. 411.↩

- Abella, Rosalie Silberman. “The Dynamic Nature of Equality” in Martin, Sheilah L. and Mahoney, Kathleen E., eds. Equality and Judicial Neutrality (Toronto: Carswell, 1987) 3 at pp. 8-9.↩

- Interview of M. Pawagi for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- The Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee, Interim Report, September 1990, p. 20.↩

- Bigelow, S. Tupper. A Manual for Ontario Magistrates (Toronto: F. Fogg, Queen’s Printer, 1962), p. 176.↩

- Ottawa Journal, May 14, 1956.↩

- Transcript of T. Andrews’ oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1995 (used with permission).↩

- Bigelow. A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, p. 176.↩

- Bigelow. A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, p. 175.↩

- Bigelow. A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, p. 31.↩

- Bigelow. A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, p. 55.↩

- Glasbeek, Amanda. Feminized Justice: The Toronto Women’s Court 1913-1934 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009), p. 33.↩

- The Police Magistrates Amendment Act, 1921, S.O. 1921, 11 Geo. V, c 41 (assented to April 8, 1921).↩

- The Canadian Encyclopedia (online), “Emily Murphy.”↩

- Provincial Courts Act, S.O 1968, c 103 (proclaimed December 2, 1968).”↩

- Mewett, Alan W. Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on the Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario, Part II: Native Communities and Remote Areas, at p. 10.”↩

- Mewett. Part II, at p. 8. ↩

- Mewett. Part II, at p. 16. ↩

- Michel, Gérald. Provincial Courts in Northern Ontario, an unpublished document provided to OCJ History Project, 2014, pp. 24-25. ↩

- Michel. Provincial Courts in Northern Ontario, p. 25.↩

- Interview of northern judicial officers for OCJ History Project, 2013. ↩

- Interview of northern judicial officers for OCJ History Project, 2013. ↩

- Vanek, David. Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge (The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History: 1999), pp.216 and 219. ↩

- Batten, Jack, Judges (Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, 1986), p. 91 ↩

- Interview of M. Hogan for OCJ History Project, 2013.↩

- Interview of S. Dunn for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Interview of M. Landsberg for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Landsberg, Michele. “Native judge shows system can change,” Toronto Star, March 5, 1991.↩

- Interview of H. Hassan for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Amendment to the Courts of Justice Act passed in 1994, and proclaimed on February 28, 1995.↩

- Interview of P. Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- In R. v. Askov, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 1199.↩

- Interviews of H. Hampton and P. Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Interviews of H. Hampton and P. Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Official Reports of Debates (Hansard), 35 (26 March 1991) “Court System” (Hon Howard Hampton).↩

- Canada’s first woman native judge, referred to by H. Hampton, was Terry Vyse.↩

- Legislative Assembly, Hansard, March 26 1991.↩

- Omatsu. “The Fiction of Judicial Impartiality,” p. 8.↩

- Omatsu. “The Fiction of Judicial Impartiality,” p. 2; Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers website (accessed January 9, 2015).↩

- Interview of P. Russell for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Omatsu. “The Fiction of Judicial Impartiality,” p. 12.↩

- Omatsu. “The Fiction of Judicial Impartiality,” pp. 9-12.↩

- Interview of M. Omatsu for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Report of a Judicial Inquiry Re: His Honour Judge W. P. Hryciuk, A Judge of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), Madam Justice J. MacFarland, Commissioner, Toronto, 1993, p. 49. ↩

- In 1994, the Divisional Court upheld the Commissioner’s findings which recommended Hryciuk’s removal from judicial office (Hryciuk v. Ontario (Lieutenant Governor) (1994), 18 O.R. (3d) 695). However, a 1996 decision of the Ontario Court of Appeal quashed the Commissioner’s findings and recommendation (Hryciuk v. Ontario (Legislative Assembly), (1996), 31 O.R. (3d) 1). The Court of Appeal found that the Commissioner had exceeded her jurisdiction by hearing three misconduct complaints in addition to the two that had been previously investigated by the Judicial Council and specified in the Order-In-Council. ↩

- Mewett. Part II, at p. 24.↩

- Justices of the Peace Act, RSO 1990, c J.4, s.2.1 (12), paragraph 6.↩

- Per diem judges and justices of the peace are those who have elected to sit on a part-time basis upon retirement from full-time work.↩

- Submitted by J. Beaman to the OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of J. Bouchard for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Submitted by D. Cole to the OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- See, for example, s. 530, Criminal Code.↩

- The Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee, Interim Report, September 1990, p. 16.↩