R. v. Parker: Medical Marijuana

R. v. M.(S.): Judge Dunn Raises A Danger Signal

R. v. Hollinsky: A Case That “Broke New Ground”

Re K.: “Same-Sex Adoption”

R. v. Deane: The Trial of Kenneth Deane

R. v. Munro: A Corruption Case Against a Former Federal Cabinet Minister

R. v. Parker: Medical Marijuana[1]

Justice Marc Rosenberg, Ontario Court of Appeal, R. v. Parker, 49 O.R. (3d) 481

Terry Parker was no stranger to the courts of Ontario. His involvement in many legal proceedings related to marijuana, an illegal drug which helped to control his epileptic seizures.

Parker achieved some success in 1987. During a criminal trial at the Provincial Court in Brampton, evidence was presented to establish that Parker’s use of marijuana was medically necessary. As a result, Judge Kenneth Langdon acquitted him of marijuana possession due to the common law defence of “necessity.” That decision was upheld on appeal.

Parker’s main claim to fame, however, arose from a trial that took place 10 years later. In that case, both the trial judge and the appeal court found the federal drug law to violate Parker’s rights under Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In response, the federal government issued regulations for the medical use of marijuana. Pending the federal changes, a personal exemption in the Court of Appeal’s decision meant that Parker became legally authorized to use marijuana in Canada.

The Trial

Judge Patrick Sheppard, Ontario Court (Provincial Division), R. v. Parker, [1997] O.J. No. 4923

Parker’s case came before Judge Patrick Sheppard of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) in 1997.[2]The charges were simple possession of marijuana, possession for the purpose of trafficking, and cultivation of marijuana. Both the Crown and defence counsel called expert witnesses.

Parker was found guilty of the trafficking charge because he admitted he gave some marijuana to people who needed it.

The other charges against him were stayed because Sheppard found that the broad legal prohibition against marijuana infringed Parker’s rights under Section 7 of the Charter. Sheppard decided to “read into” the legislation an exemption for medically approved marijuana use.

Sheppard also ordered the return of three marijuana plants that the police had seized from Parker’s apartment.[3]

Section from the Charter of Rights and Freedoms considered in R. v. Parker

Life, liberty and security of the person

7. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.

The Appeal

The decision to stay the charge against Parker for possession of marijuana was appealed by the Crown. On July 31, 2000, a panel of three Ontario Court of Appeal judges – Justices Catzman, Charron and Rosenberg – released their historic decision.

The panel agreed with Sheppard’s decision to stay the charge on the basis of Section 7 of the Charter. However, it disagreed with the remedy of “reading in” an exemption. Instead, the Court declared that the prohibition of marijuana possession in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act was invalid. It suspended this declaration for one year — to give Parliament time to “craft satisfactory medical exemptions.”[4] Terry Parker was given a personal one-year exemption to possess marijuana for his medical needs.

The Court of Appeal also disagreed with Sheppard’s decision to require the police to return the plants “as there was no evidence that these perishable items were still available.”[5]

The Government Response

The clock was ticking. Parliament had one year to revise the marijuana prohibition before the Court of Appeal’s ruling would render the law invalid. Parliament did not act during the one-year period. However, the executive branch of government did – one day before the deadline.

The Medical Marihuana Access Regulations came into force on July 30, 2001.[6] The regulations created a process for individuals to obtain a permit to possess and produce marijuana for personal medical use.

This is an example of court decisions resulting in government legal and policy changes, even though the matter was not part of the government’s public policy platform.

Health Canada website (accessed November 2014)

Postscript – Another Trip to Provincial Court

In December 2007 – 20 years after the trial where Terry Parker claimed that marijuana was a medical necessity, and 10 years after claiming a breach of Charter rights – he appeared before Justice S. Ford Clements of the Ontario Court of Justice.[7] Parker was not facing criminal charges. This time he was in court asking for the return of marijuana that Canada Post had seized and turned over to the Peel Regional Police.

Clements dismissed the application. Parker appealed twice – first to the Superior Court of Justice[8] and subsequently to the Ontario Court of Appeal.[9] Both appeals were dismissed.

The main reason Parker did not succeed was his lawful entitlement to possession of marijuana was not established – he simply had not sought or received a permit for medical use under the federal regulations. The man whose landmark case resulted in the very existence of Canada’s medical marijuana rules had failed to take advantage of them.

| Provincial Court | 1987

Parker is acquitted of marijuana possession due to the defence of “medical necessity.” |

1997

The legal prohibition against possessing marijuana is found to breach Parker’s Charter right to life liberty and security of the person. |

2007

Parker’s application for the return of seized marijuana is dismissed because he never obtained a permit for legal medical use. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appeal | 1988

Parker’s acquittal is upheld by the District Court. |

2000

The Ontario Court of Appeal declares the law to be invalid, but suspends the declaration for one year. |

2009 & 2011

The Superior Court and Ontario Court of Appeal agree with the dismissal. |

- R. v. Parker, [1997] O.J. No. 4923; 12 C.R. (5th) 251; 48 C.R.R. (2d) 352 – Trial Decision, December 10, 1997, Judge Patrick Sheppard. R. v. Parker, [1997] O.J. No. 4550 – Trial Motion, October 30, 1997. R. v. Parker, [2000] O.J. No. 2787; 49 O.R. (3d) 481; 188 D.L.R. (4th) 385; 135 O.A.C. 1; 146 C.C.C. (3d) 193; 37 C.R. (5th) 97 – Court of Appeal Decision, July 31, 2000. ↩

- Due to restructuring of the Court in 1990, the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) had replaced the former Provincial Court (Criminal Division). ↩

- Sheppard, R. v. Parker, [1997], Trial Decision, para. 70. ↩

- Court of Appeal, R. v. Parker, [2000], para. 198. ↩

- Court of Appeal, R. v. Parker, [2000], para. 196.↩

- S.O.R./2001-227. ↩

- Due to further restructuring in 1990, the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division) became known simply as the Ontario Court of Justice. ↩

- R. v. Parker, [2009] Canlii 51515 (ON SC) (Tulloch, J.). In his reasons, Justice Tulloch referred to Justice Clements as having dismissed the application “in a very thorough and reasoned decision.” The reasons of Justice Clements appear to be unreported. ↩

- R. v. Parker, (2011), 286 O.A.C. 219 (CA); 2011 ONCA 819. ↩

R. v. M.(S.): Judge Dunn Raises A Danger Signal[1]

Judge Patrick Dunn

The parents of a twelve-year-old babysitter were shocked when their daughter was accused of shaking a toddler to death. They believed her explanation that the child had accidentally fallen down a few steps. The coroner initially ruled that death had resulted from a head injury caused by an accidental fall. Doctors at the Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) – where the child was transferred after initial treatment at St. Mary’s Hospital in Timmins – thought otherwise. Leading the charge was Dr. Charles Smith, a pathologist who would later be disgraced in a public inquiry. The child’s body was exhumed, Smith performed an autopsy, and the babysitter was charged with manslaughter.

The trial, heard by Judge Patrick Dunn in the youth court of the Provincial Court (Family Division) entailed 30 days of hearings between October 2, 1989 and November 6, 1990. A judgment was issued on July 25, 1991.

The prosecutors relied heavily on testimony from Smith and others from SickKids. While this evidence at first appeared to be plausible, it was strongly discredited by expert witnesses presented by the defence. Had the expert evidence not been available, it is very possible that the babysitter – referred to in the judgment as “Shelly M.” – would have joined the ranks of persons wrongfully convicted due to flawed pediatric pathology. Instead, she was acquitted.

Several participants played a part in achieving a fair and just result in this case, as opposed to other trials that had involved Smith.

The Babysitter

Judge Dunn found Shelly M. to be a credible witness.

The Babysitter’s Father

Shelly M.’s father had a research and science background. He devoted himself to learning everything he could about medical theories regarding shaken baby syndrome, falls, and head trauma. He contacted leading experts from across North America and paid for nine of them to come to Timmins to testify at the trial.[3] The family endured financial hardship to pay for the legal defence.

The Defence Counsel

The defence counsel was Gilles Renaud, who was later appointed as a judge of the Ontario Court of Justice. His presentation of the expert evidence and cross-examination of the prosecution witnesses was compelling. During his 1995 swearing-in ceremony, Renaud graciously acknowledged the role played by Shelly M.’s father, lauding him for being the best assistant a courtroom lawyer could have.[4]

The Experts

Leading experts in pediatric neuropathology, biomechanics, neurosurgery, pediatrics, and radiology brought into sharp focus the deficiencies in the autopsy and the opinions of the prosecution’s main witness. They were also able to show that serious head injuries to a child can occur from a short fall with minimal visible indication of trauma.

The Judge

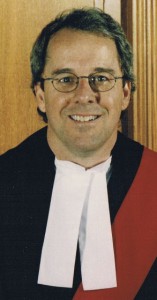

Judge Dunn carefully considered a large quantity of technical medical and scientific evidence. He then prepared detailed reasons for judgment that explain why he favoured the defence experts as opposed to those led by the prosecution. Years later, when releasing his report for the Inquiry into Pediatric Forensic Pathology in Ontario, Justice Steven Goudge stated, “I also address the important role the judiciary has to play in screening out unreliable forensic pathology evidence.” Judge Dunn did just that.

What Went Wrong?

Judge Patrick Dunn[5]

Judge Dunn’s decision included numerous criticisms of Dr. Smith’s methodology, practice and theories, among them the following:

- Smith did not seriously consider possibilities other than shaking.

- He viewed the purpose of an autopsy as trying to find another cause of death.

- He assumed that certain bruises predated the collapse, without sufficient knowledge of the case.

- Smith formed his diagnosis of shaking before he knew the weight and size of the child.

- He provided very little detail in his autopsy report.

- He did not consult with the relevant physicians before conducting the autopsy.

- He appeared to have reached a conclusion before the autopsy was complete.

- Smith was not familiar with the latest medical literature.

Judge Dunn further wrote: “I cannot explain how doctors from Ottawa, Winnipeg, Bethesda, Maryland, Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles and even Dr. Sullivan from Timmins can come to this court and say they are not surprised by serious head injuries in children from low falls, while four specialists from Toronto say it is out of their experience. Dr. Smith even said it could not happen.”[6]

The Goudge Inquiry

Former Chief Justice Brian Lennox.[7]

On April 25, 2007, sixteen years after Judge Dunn’s decision, the provincial government established the Inquiry into Pediatric Forensic Pathology in Ontario. The mandate was to determine “what went so badly wrong in the practice and oversight of pediatric forensic pathology in Ontario” and to make recommendations to restore public confidence.[8]

Led by Justice Steven T. Goudge of the Court of Appeal for Ontario, the Inquiry reviewed 20 cases about which the Chief Coroner’s Review had expressed serious concerns arising from Dr. Smith’s work. This included the case of “Amber”, the toddler whose death resulted in the charges against Shelly M.

Justice Goudge’s report describes the career of Dr. Smith as follows:

From 1981 to 2005, Dr. Smith worked as a pediatric pathologist at Toronto’s world-renowned Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). Although he had no formal training or certification in forensic pathology, as the 1980s came to an end he started to become involved in pediatric cases that engaged the criminal justice system. Then, in 1992, he was appointed director of the newly established Ontario Pediatric Forensic Pathology Unit (OPFPU) at SickKids. He soon came to dominate pediatric forensic pathology in Ontario.[9]

Given his position and assumed qualifications, Dr. Smith’s courtroom testimony could no doubt be persuasive if his methodology, knowledge and conclusions went unchallenged by actual expert witnesses.

A Missed Opportunity

The Goudge Report cites Justice Dunn’s R. v. M.(S.) decision in favourable terms and expresses frustration that health care regulators and overseers did not take it seriously. Had they done so, subsequent wrongful convictions might never have occurred.

Almost all of Justice Dunn’s criticisms have stood the test of time. Most of the weaknesses that Justice Dunn identified in Dr. Smith’s forensic pathology reappeared in Dr. Smith’s work in criminally suspicious cases over the next decade. Justice Dunn’s judgment proved to be prophetic.

…Justice Dunn’s decision raised a danger signal about Dr. Smith’s competence and professionalism. Unfortunately that signal was ignored and any opportunity for re-evaluation of Dr. Smith’s work was lost.[10]

Justice Dunn strongly criticized Dr. Smith in detailed reasons for judgment, which expert witnesses at the Inquiry described as a “masterful analysis” of the forensic pathology issues raised in the case.[11]

Blaming the Judge

While the College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario eventually took action, for a long time they took Smith’s comments at face value. As an example, Smith falsely asserted that “Justice Dunn had a change of heart and admitted…that, had he fully understood the medical evidence presented at the trial, he would have convicted S.M. of the manslaughter charge.”[12]

The Amber case was featured in an episode of The Fifth Estate, televised in November 1999. In his interview for the program, Dr. James Cairns (Deputy Chief Coroner from 1991 to 2008) referred to Smith as “top notch” and made the following comment about Justice Dunn’s decision: “I, with due respect, feel that the medical evidence was confusing and that the judge may not have clearly understood all the evidence that was being given.”[13] A few years later, in an interview with Maclean’s Magazine for an article entitled “Dead Wrong,” Dr. Cairns referred to Smith as a “wonderful asset.”[14]

The Judge’s Affidavit

Lawyer Harold Levy in “The Charles Smith Blog” (January 27, 2008)

In December 2007, Justice Dunn provided an affidavit for the Goudge Inquiry to counter statements made about him by Dr. Smith. The contents of the affidavit went undisputed by Dr. Smith. The Goudge Report makes reference to this document as follows. “In his affidavit, Justice Dunn wrote that, although he and Dr. Smith were on the same flight during the trial, they simply exchanged pleasantries and did not discuss the case. While he did not have a specific recollection of his conversation with Dr. Smith, Justice Dunn swore: ‘I am certain that I did not discuss the merits of the case or the evidence with Dr. Smith. I may have commented on the Susan Nelles case because I understood Dr. Smith had some involvement in that case.’ According to Justice Dunn, “[a]t no point during the course of the trial did I discuss Dr. Smith’s evidence with him or indicate to Dr. Smith that I believed [S.M.] to be guilty.”[15]

Conclusion

Judges make findings based on the evidence in front of them. In the case against Shelly M., her defence counsel and family ensured that leading North American experts were present to provide a compelling array of evidence which the trial judge found to be highly credible. Other people charged with having killed children based on pathology evidence from Dr. Charles Smith were not as fortunate. Although the world of a twelve-year-old babysitter and her family were shaken for years, when the matter came to trial in a Timmins courtroom, justice was served.

- R. v. M.(S.) [1991] O.J. No. 1383, p. 32. It is to be noted that until 1999, judges of the Provincial Court used the honorific “Judge.” From 1999 onwards, judges of the Ontario Court of Justice are referred to as “Justice.” This explains the references to “Judge Dunn” and subsequently “Justice Dunn.” ↩

- R. v. M.(S.), p.32. ↩

- Boyle, Theresa Father credited with acquittal in baby’s death, Toronto Star, Theresa Boyle, Friday April 4, 2008. ↩

- Interview of G. Renaud for OCJ History Project, 2015. ↩

- R. v. M.(S.), p. 21, p.25.↩

- R. v. M.(S.), p. 25. ↩

- Interview of former Chief Justice Brian Lennox for OCJ History, 2014. ↩

- Ontario Report of Inquiry into Pediatric Forensic Pathology in Ontario, Volume 1, pp. 5-6 (“Goudge Inquiry”). ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 1, p. 6. ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 2, p. 13. ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 2, p. 208. ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 2, p. 13. ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 2, p. 229. ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 2, p. 238. ↩

- Goudge Inquiry, Volume 2, p. 194. ↩

R. v. Hollinsky: A Case That “Broke New Ground”

Early in the morning of July 30, 1994, 19-year-old Kevin Hollinsky was behind the wheel in a car with three of his friends, Joseph Camlis, Andrew Thompson, and Todd Giles, as passengers. Hollinsky was driving fast – above the speed limit – and aggressively, overtaking and cutting in front of one car, then closely following another before pulling out to overtake it as well. While passing the second car, Hollinsky’s vehicle skidded out of control, struck two hydro poles, and came to rest on a residential front lawn. Camlis and Thompson died as a result of injuries sustained, while Giles suffered non-critical injuries to his mouth and punctured a lung. Hollinsky escaped uninjured.

Hollinsky Accepts Responsibility, Pleads Guilty

The criminal trial against Hollinsky was heard at the Ontario Court of Justice in Windsor before Justice Saul Nosanchuk.

Although the young men – including Hollinsky – had been consuming alcoholic beverages, the Crown Attorney withdrew impaired driving charges, stating that it could not be established that the accident was the result of impairment. Instead, the Crown proceeded with two counts of driving a motor vehicle in a manner that was dangerous to the public, thereby causing death. Hollinsky accepted responsibility and pleaded guilty before the commencement of the preliminary hearing.

At sentencing, the Crown and defence agreed that there was no need to deter Hollinsky from reoffending in this manner. As Justice Nosanchuk observed, the victims “were his very best friends and the enormity of the loss will unquestionably deter him from committing a similar offence in the future.”[1] The question for Nosanchuk was how best to achieve the sentencing objective of general deterrence – deterring the public at large from driving dangerously and risking similar tragedies. The Crown argued that Nosanchuk should impose a prison term of eight-to-twelve months. Defence counsel argued that rather than sentencing Hollinsky to prison, Nosanchuk should require him to perform community service instead.

Support from the Victims’ Families

Hollinsky had the “overwhelming and unqualified support” of both victims’ families.

There was a recognition by them of the obvious guilt that would be suffered by Kevin Hollinsky for many years, if not for the rest of his life, as a result of the commission of the offence. There was a recognition of the torment that he has gone through and will continue to go through. There was an absence of bitterness and a desire to take positive and healing steps. There was a determination to participate in a program of public education to prevent such a tragedy from recurring as a tribute to the memories of Joseph Camlis and Andrew Thompson.[2]

Specifically, the families of the two victims proposed that Hollinsky join them in speaking to high school students about the imperative to drive responsibly.

Sentencing Hollinsky: “Incredibly Difficult”

Nosanchuk described the task of sentencing Hollinsky as “incredibly difficult.”[3] The judge had “no doubt that Kevin Hollinsky would gladly serve any amount of time in prison in exchange for the return of his deceased friends” who were “like brothers to him.”[4] But a custodial sentence would not bring the victims back – nor, in Nosanchuk’s view, would it achieve the objective of general deterrence nearly as well as the community service plan proposed by Hollinsky’s counsel and the families of the deceased young men. Although there were few precedents for a non-custodial sentence for dangerous driving offences at that time, Nosanchuk took the bold step of sentencing Hollinsky to three years’ probation and 750 hours of community service.

The sentence attracted a great deal of public interest and controversy. Some praised the sentence Nosanchuk imposed as meaningful, constructive, effective, and less costly to taxpayers.[5] Others saw it as unduly lenient, at least initially. Those opinions changed as Hollinsky served his sentence. By November 1995, Hollinsky had spoken to 8,300 high school students in the Windsor area. At each appearance he was accompanied by Andrew Thompson’s father, and by the Pontiac Sunbird he’d been driving that night, now a crumpled, blood-stained wreck.

These talks were coordinated by Staff Sergeant Lloyd Graham, the Windsor Police officer in charge of community policing. A 30-year veteran of the police force and self-described “law and order kind of guy”, Graham was surprised by the sentence Nosanchuk imposed. Based on his experience and the fact that two people had been killed, Graham expected a jail term would be imposed. Community service would be “a walk in the park; he’s not going to jail – he’s getting off scot free. It looks like a slap on the wrist.” Graham “didn’t agree at first [with the sentence]… and there were a lot of people around this police service that didn’t agree. They thought it was wrong, basically wrong, a young man takes two lives, he shouldn’t be allowed to just walk free.”[6] But after watching Hollinsky speak, Graham changed his mind. Graham saw the incredible emotional toll of re-living the collision over and over again, ultimately referring Hollinsky to a psychologist to be treated for post-traumatic stress disorder. Graham also saw the profound benefit to the community.

Every summer we lose kids in this community, in this county. I asked someone to call the schools [that we did talks at] and check to see if there had been any tragedies over the summer. It was reported back to me that not one school reports any tragedies involving any of their students, tragedies such as drinking [and] driving fatalities. I think the community has won big-time here. If you put him in jail, sure, we get our pound of flesh, Kevin goes to jail. Who wins out of that? How does the community benefit from that? Kevin would be in jail and there would be 8,300 kids out there who wouldn’t get the specific message. I think he deterred a great percentage of those kids from drinking and driving.[7]

Fresh Evidence at the Court of Appeal

The Crown appealed the sentence, but it was upheld by the Court of Appeal, which had before it fresh evidence about the community service Hollinsky had performed. A brief endorsement was included in the dismissal of the Crown’s appeal.

We have had the benefit of viewing the results of this performance by the respondent of the community services required from him as part of his sentence and in particular his participation in appearing before more than 8,300 students on 14 occasions emphasizing the terrible consequences of dangerous driving while drinking. The fresh evidence filed on behalf of the respondent is indicative of the powerful deterrent effect of this type of program as projected by the trial judge.[8]

Breaking New Ground

Years later, Nosanchuk’s decision was celebrated for breaking new ground, and for exemplifying the judge’s courageous and compassionate approach to the task of judging. When Nosanchuk retired in 2006, renowned criminal lawyer Eddie Greenspan, who represented Hollinsky on appeal, said that the case “best defined” Nosanchuk as a judge. “The judgment was highly controversial,” Greenspan said. “It took guts, determination, and most of all a tremendous heart.”[9] Patrick Ducharme, who had represented Hollinsky at the sentencing hearing, recalled the impact of the deceased youths’ parents’ expressions of anguish: “I couldn’t help but notice tears, big teardrops, streaming down Saul’s glistening cheeks as he listened to this testimony and as he [Nosanchuk] fashioned that unique and interesting and brave sentence.”[10]

In his reasons for sentence, Nosanchuk praised the conduct and attitude of the parents of the victims, describing them as a “tribute to the capacity of the human spirit to respond affirmatively and with profound compassion to an awful tragedy.”[11] The sentence imposed – one that has been replicated many times since by judges throughout the provincial courts across Canada – demonstrated the Court’s capacity to do the same.

- R. v. Hollinsky, [1995] O.J. No. 4126 (CJ (Prov. Div.)) at para 6.↩

- Ibid. at para 7↩

- Ibid. at para 11.↩

- Ibid. at paras 26, 25.↩

- See, e.g. Rick Prashaw, Coordinator, Communications, Church Council on Justice and Corrections, Presentation to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Justice and Legal Affairs, Thursday, April 18, 1996.↩

- Bob Carty, Producer, “Kevin’s Sentence,” CBC Radio Sunday Edition, 1995.↩

- Ibid.↩

- R. v. Hollinsky, [1995] O.J. No. 3521 (C.A.)↩

- Ron Stang, “Nosanchuk always ready to take a chance for justice,” Law Times, April 10, 2006.↩

- Ibid.↩

- R. v. Hollinsky [1995] O.J. No. 4126 at para 9.↩

Re K.: “Same-Sex Adoption”

This article is excerpted from “Celebrating equality and the rule of law,” an article published in the Ontario Lawyers Gazette (The Law Society of Upper Canada, Summer 2011, Vol 15, No.2., pp.5-6). Reprinted with permission of the Law Society of Upper Canada.

Note: Janet Minor is referred to throughout this article as a Bencher. She was elected Treasurer of the Law Society in June 2014.

In the mid-1980s, a lesbian couple, Miriam Kaufman, a doctor, and Roberta Benson, a lawyer, decided that they would raise a family together. Miriam gave birth to two children: a son, Jacob and a daughter, Aviva.

Despite the fact that they were clearly a family, the law did not recognize Roberta as the legal parent of the two children. The obvious answer was for Roberta to adopt Jacob and Aviva. However, at that time, the adoption legislation only allowed opposite sex couples to adopt their partner’s children.

In 1994, Ontario’s first female Attorney General, Marion Boyd, introduced legislation to amend all Ontario laws, so same-sex couples would have the same rights as opposite-sex couples. Ms. Boyd believed that, otherwise, Ontario’s laws infringed the equality provisions of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

There was a great deal of controversy over this bill. Ultimately, a free vote was held in the legislature. Some of the members of government voted against the bill, and it was defeated on second reading. In the provincial election that followed, the issue of same sex benefits was a major campaign issue. Miriam, Roberta, Jacob and Aviva, were left legally vulnerable.

After the bill’s defeat, with three other lesbian families, Miriam and Roberta decided to take action. They retained the now Treasurer, Laurie H. Pawlitza, to bring a Charter challenge to the adoption legislation that prevented them from both being the legal parents of their children. When the challenge was launched, Attorney General Boyd intervened in the adoption case, and asked her lawyer, Crown Attorney and now Law Society Bencher, Janet Minor, to make arguments both for and against the validity of the adoption legislation. The Attorney General also conceded that the legislation was unconstitutional.

The case came before the Honourable Justice James Nevins of the Ontario Court of Justice. Justice Nevins found that the law precluding the adoptions was unconstitutional. In May 1995, he granted adoption orders to four non-biological mothers who were co-parenting their partners’ children.[1] The children, son, Jacob and daughter, Aviva, were part of that group.

Jacob Kaufman was called to the Bar at the June 16, 2011 ceremony. Together at the call were former Attorney General and Lay Bencher Marion Boyd, Bencher Janet Minor and the Honourable Justice Nevins. Treasurer Laurie H. Pawlitza, the Benson-Kaufman’s lawyer in the adoption case, presided over the call.

Call to the Bar, June 16, 2011

Back row, left to right: Law Society Treasurer Laurie H. Pawlitza, Roberta Benson, Miriam Kaufman, Law Society Bencher Janet Minor. Front row, left to right: The Honourable Justice James Nevins, new lawyer Jacob Kaufman, Former Attorney General and Law Society Lay Bencher Marion Boyd. (Courtesy: The Law Society of Upper Canada)

- Re K. [1995] OJ 1425.↩

R. v. Deane: The Trial of Kenneth Deane

Although R. v. Deane was decided in 1997, the events giving rise to it stretched back at least 170 years. In 1827, the Chippewas signed the Huron Tract Treaty, ceding 2.1 million acres – 99 percent of their traditional territory – to the Crown. Four reserves were created out of the unceded territory, two of which were located at Kettle Point and Stoney Point, on the shores of Lake Huron not far from present-day Sarnia.

The History of Expropriation and Surrendering of Portions of Reserves

Beginning in the early 1900s, the Kettle and Stoney Point First Nations were pressured to surrender part of their reserves. In 1927, 27 of the 39 eligible First Nations voters voted to approve the surrender of much of the Kettle Point beachfront. Despite protests that the approval had been obtained through bribery and fraud, the federal Department of Indian Affairs proceeded with the surrender. The next year, 377 acres of the Stoney Point Reserve – 14 per cent of the total land and the entire beachfront – were surrendered following “extreme pressure”[1] exerted by the local Indian Agent.

In 1932, local residents began petitioning for the creation of a park at Stoney Point in order to preserve a public beach and waterfront access. In 1936, the Ontario government purchased one of the lots that had been sold to private developers following the 1928 surrender. That lot became Ipperwash Provincial Park. The following year, the Chief and Council of the Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation advised that there was a burial ground located in the park and asked that it be protected. The Ontario government took no steps to do so.

During World War II, the federal Department of Nation Defence (DND) decided it wanted to establish a training camp on what remained of the Stoney Point Reserve. Despite protests by the Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation, the Indian Agent, who was authorized to act on behalf of the federal government with the people of the First Nation, called a surrender vote. Of the 72 eligible voters who attended the meeting, 59 voted against the surrender. The DND nevertheless expropriated the Reserve using the powers under the War Measures Act. The Order-in-Council giving effect to the surrender acknowledged that the First Nation had voted against the government proposal, and stated that if the DND ceased to require the land after the war it would negotiate to return the land to the First Nation at a fair price.

Calls for the Return of the Land

Residents of Stoney Point were evicted from their land and forcibly relocated to Kettle Point. First Nations soldiers from the Stoney Point Reserve returned from serving overseas in the Canadian military to find their homes bulldozed and their community fractured. The discovery that gravesites and burial grounds had been desecrated was particularly devastating. The Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation repeatedly sought the return of the land the DND called Camp Ipperwash, but to no avail. Finally, in May 1993 – more than 50 years after the land was appropriated – a group from Stoney Point peacefully occupied the military ranges at Camp Ipperwash. Still the land was not returned.

The Backdrop, The Protest

It was against this backdrop of appropriation and decades of inaction on the government’s promise to return the Stoney Point Reserve that the protest intensified. In late July 1995, First Nations protesters entered the military camp itself. Although there were “mini confrontations” the commanding officer made it clear he did not wish to be involved in a physical confrontation with First Nations people. Military personnel left without incident later that night. On September 4, 1995, protesters entered Ipperwash Provincial Park, where the First Nation had long maintained there were burial grounds. It was Labour Day Monday – the end of the long weekend and the beginning of a new school year – and protesters waited until the park had closed for the day before beginning their occupation.[2]

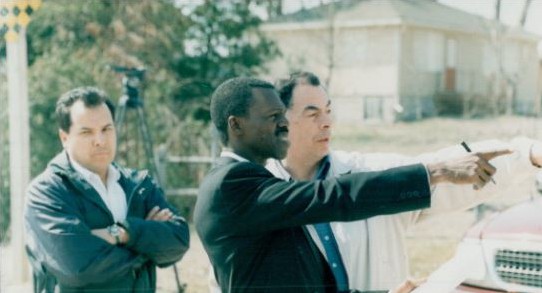

By the evening of September 6, the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) had established a tactical operation centre about half a kilometre west of the Park.[3] At approximately 10:45 p.m., the OPP’s Crowd Management Unit marched toward the fence bordering the park. When they arrived at the fence, they ordered the occupiers to get out of the park. A confrontation ensued. At least 15 of the occupiers came over the fence to attempt to rescue a protester who was allegedly being beaten by police. At the same time, a large yellow school bus left the park and drove in the direction of the officers, forcing them to scatter and retreat. A car followed the bus, and then both vehicles reversed. Police opened fire as the vehicles were reversing.[4] Three distinct gunshots were heard, followed by a brief lull and then a rapid burst of gunfire.[5]

Dudley George is Shot

Dudley George, one of the First Nations occupiers on the ground, exclaimed “I think I’m hit” before collapsing.[6] With no time to wait for an ambulance, his brother and sister drove him to Strathroy General Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 2:00 a.m. on September 7, 1995.[7] George was “the only Aboriginal person killed by a police officer in a land claims dispute in Canada in the twentieth century.”[8]

That officer was Kenneth Deane, a veteran member of the OPP’s paramilitary Tactics and Rescue Unit deployed to support the Crowd Management Unit. There was no dispute that Deane fired the fatal shot. The only question was whether he was acting in self-defence at the time he did so.

The Trial of Kenneth Deane

Deane was charged with criminal negligence causing death. His trial was heard at the Ontario Court of Justice in Sarnia by Justice Hugh Fraser.

At the trial, Deane testified he’d seen muzzle flashes coming from inside the school bus, and then saw George run out from the bushes onto the road, shouldering a rifle. Deane said he shot George to “stop the threat of being shot at.”[9] According to Deane, George threw his rifle into a nearby ditch after being hit.

Despite the presence of other officers in the area where Deane had claimed George disposed of a rifle, he had not alerted them to the presence of a weapon. No rifle was ever recovered and Deane’s evidence was contradicted by that of other officers. Notably, Sergeant George Hebblethwaite, a 20-year veteran of the OPP, testified that he had seen George “holding an object which I perceived to be a pole or a stick” – not a rifle as Deane claimed.[10] Hebblethwaite did not perceive the pole or stick George held to be a threat.[11] He confirmed that no police-issue equipment appeared to have been damaged by bullets, and that he never saw a firearm in the hands of any of the First Nations occupiers that night.[12]

The Court Rejects Deane’s Account

Judge Hugh Fraser, who presided over Deane’s trial, rejected the accused’s account of the events. He noted that Hebblethwaite, whom he characterized as a helpful and credible witness, was standing behind Deane and thus further away from George at the time he was shot, but had no difficulty identifying the object George held as a pole or a stick. Fraser also noted that there were “no Crown witnesses or defence witnesses that saw any weapons in the hands of the First Nations people” except for Deane and OPP Constable Chris Cossett – a witness whose testimony Fraser described as “clearly fabricated and implausible.”[13] Fraser found the same to be true of Deane’s evidence.

In the Court’s view this is not a situation of honest but mistaken belief. The accused has maintained throughout that Dudley George was armed. And the accused was able to even describe some of the features of the rifle that he saw Dudley George holding.

I find that Anthony O’Brien (Dudley) George did not have any firearms on his person when he was shot. I find that the accused Kenneth Deane knew that Anthony O’Brien Dudley George did not have any firearms on his person when he shot him. That the story of the rifle and the muzzle flash was concocted ex post facto in an ill-fated attempt to disguise the fact that an unarmed man had been shot.[14]

Fraser concluded by addressing Deane directly.

I find sir that you were not honest in presenting this version of events to the Ontario Provincial Police investigators. You were not honest in presenting this version of events to the Special Investigations Unit of the Province of Ontario. You were not honest in maintaining this ruse while testifying before this Court. I have considered all of the evidence presented in this case, and on the basis of the evidence that I have accepted, I find you Kenneth Deane guilty as charged.[15]

The verdict, although welcomed by George’s family and community, offered them little in the way of closure – especially after Deane was given a conditional sentence of two years less a day to be served in the community. Too many questions remained about how a peaceful protest could have escalated to result in a violent death so quickly, and why the OPP moved in so abruptly, at night, to remove the protesters from the Park. Finally, after years of pressure from the George family, repeated questions raised in the Ontario legislature, and continued investigation by journalists, a public inquiry was established in November 2003 by the newly elected Liberal government.

The Ipperwash Inquiry is Called

The Ipperwash Inquiry was mandated to investigate and report on the events surrounding George’s death, as well as to make recommendations that would avoid violence under similar circumstances in the future. Sidney Linden, a judge and former Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice, was appointed Commissioner. Hearings were held over a number of days between July 2004 and November 2005. Deane was scheduled to testify at the inquiry, but was killed in a traffic accident just weeks before he was to appear.

The four-volume Ipperwash Inquiry Report was released on May 30, 2007. Linden found that the OPP, the provincial government led by Premier Mike Harris, and the federal government all bore responsibility for the events that led to George’s death. Linden also called on the federal government to issue a public apology and return Camp Ipperwash – along with compensation – to the Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation. The Ontario government responded to Linden’s recommendations by creating a dedicated Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs. It also agreed to return the Ipperwash Provincial Park lands purchased in 1936 to the Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation. A 2010 announcement confirmed transfer of the land to the federal government, which alone has the power to designate reserve territory. However, while the federal government subsequently engaged in negotiations about the return of Camp Ipperwash, as of 2015 – 20 years after Dudley George was killed – the land still had not been returned.[16]

Conclusion

The Ipperwash protest and its aftermath were memorable and controversial developments in Ontario’s history. The Ontario Court of Justice played two roles in attempting to resolve some of the issues. The first occurred when Justice Hugh Fraser presided over the criminal trial of the officer accused of killing Dudley George. The second was when Sidney Linden, a judge and former Chief Justice of the Court, chaired the Ipperwash Inquiry.

- Ipperwash Inquiry Report, Volume 4, Executive Summary, p. 4.↩

- The background information in this and the preceding paragraphs is based on information contained in from the Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry, Vol. 4, “Executive Summary” at pp. 1-19.↩

- R. v. Deane, [1997] O.J. No 3057 (Ct J (ProvDiv)) at para 4. ↩

- Ibid. at paras 6-9.↩

- Ibid. at para 22. ↩

- Ibid. at para 31.↩

- Ibid. at para 10; Ipperwash Inquiry Report, Vol. 4, p. 73.↩

- Peter Edwards, One Dead Indian, p. 16. ↩

- R. v. Deane at paras 38-41. ↩

- Para 232.↩

- Para 259.↩

- Para. 261.↩

- Para 406.↩

- Paras 408-409. ↩

- Para 411. ↩

- Michael Bryant, “Twenty years after Dudley George’s death, land still in federal hands” Toronto Star, January 22, 2015.↩

R. v. Munro: A Corruption Case Against a Former Federal Cabinet Minister[1]

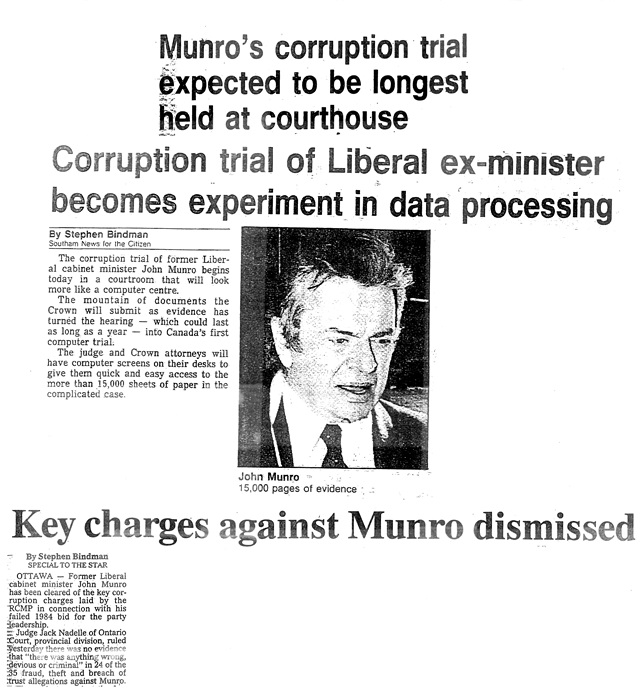

The trial of former federal Liberal cabinet minister John Munro, and six others, commenced in an Ottawa courtroom in 1990, has come to be regarded as a landmark case. It was considered to be Canada’s “first computer trial,” and culminated notably with strongly worded decisions issued by presiding Provincial Division judge, Jack Nadelle, dismissing the charges

“The Munro case was a significant catch for this Court,” recalled Nadelle.[2] The trial stemmed from corruption charges related to John Munro’s failed bid to win the leadership of the Liberal Party in 1984. This was precisely the type of “big” case that traditionally would have been heard in a superior court. In fact, all of those charged had the right to a preliminary hearing and subsequent trial by a General Division (a superior court) judge and jury. Nevertheless, all elected trial by a Provincial Division judge.

Becoming a “Specialist” Court

Reflecting on the case, Nadelle attributed the decision to proceed in Provincial Division to its growing reputation as a “specialist” Criminal Court – a court where the trial would be heard by a judge with a deep understanding of criminal law. Plus, given the magnitude and projected duration of the proceedings, the defence lawyers decided to proceed straight to trial, bypassing the preliminary inquiry stage. A preliminary inquiry, which would have been heard by a Provincial Division judge, could have lasted as long as the trial itself and resulted in considerable legal fees.

John Carr Munro was appointed Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND) in 1980. After the 1984 resignation of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Munro made an unsuccessful bid for the leadership of the federal Liberal Party. After Munro’s defeat in the September 1984 federal election, allegations of mismanagement of funds under the control of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) – funds which had been granted to the AFN by DIAND when Munro was Minister – led to an RCMP investigation of potentially illegal kickbacks into Munro’s 1984 leadership campaign.

In November 1989, charges of corruption, conspiracy, fraud, breach of trust, theft and other related offences were laid against Munro and several others, including the former leaders of several Aboriginal organizations. Of the 77 charges, 34 were laid against Munro. These charges were subsequently dismissed in the decisions released by Nadelle in November 1991.

The Courtroom as a Computer Centre

Computers in the courtroom were a novelty at that time. “The corruption trial of…Munro begins today in a courtroom that will look more like a computer centre,” wrote Stephen Bindman in the Ottawa Citizen on January 14, 1991.[3] “The mountain of documents the Crown will submit as evidence has turned the hearing – which could last as long as a year – into Canada’s first computer trial. The judge and Crown attorneys will have computer screens on their desks to give them quick and easy access to the more than 15,000 sheets of paper in the complicated case…Munro’s lawyer, John Nelligan, who will work with a laptop computer in the courtroom, said he is ‘a little nervous’ about the experiment.”[4]

Nadelle Dismisses All Charges

In his judgment, Nadelle briefly summarized the Crown’s theory: “Mr. Munro knew that his leadership bid campaign would require more funding than they could raise from usual sources…Mr. Munro then used his influence as DIAND Minister to improperly fund the AFN, knowing the AFN would use this money to contract with third parties. They would in turn give this money or part of it back to Mr. Munro in the form of donations to the Munro for Leadership campaign.”[5]

Nadelle made quick work of this theory: “I have concluded that there is no evidence that there was anything wrong, devious or criminal in the whole process…nor is there any evidence upon which one might infer that the funding was in some way tainted.”

He went on to state that it was not surprising that the Aboriginal leaders and Munro were in frequent contact because of a flurry of government activity at the time over native self-government issues: “The Crown has in my view strung together a series of routine and entirely normal-for-the-time series of meetings, funding requests, funding negotiations and bureaucratic memos, together with a group of witnesses who gave, when all was said and done, irrelevant testimony…It is true that the situation looks suspicious, primarily because of the fact Indian bands, for some time, had gotten involved in the…political process and because of the size of the donations…But there…never had been a Minister who had gained the trust and respect of the Indian groups in the manner Mr. Munro had. Naturally they hoped his political career would flourish.”[6]

Nadelle’s November 1991 decisions dismissed all charges without hearing from the defence.

His decisions in the Munro case garnered significant media attention. In particular, the media jumped on what they called the racism of the RCMP: “The whole sorry case was a punitive RCMP expedition against the native leadership and native people.”[7]

An embittered Munro – whose reputation was tarnished by the charges – spent years suing the federal government for compensation over being wrongfully charged. The government ultimately agreed to an out-of-court settlement of $1.4 million, of which $1.2 million went to Munro’s lawyers and other creditors.[8]

The Munro case was regularly in the headlines during the years it was before the Provincial Division in Ottawa.

Top to bottom: Sean Upton, “Munro’s corruption trial expected to be longest held at courthouse,” Ottawa Citizen, August 25, 1990; Stephen Bindman, “Corruption trial of Liberal ex-minister becomes experiment in data processing,” Ottawa Citizen, January 14, 1991; Stephen Bindman, “Key charges against Munro dismissed,” Toronto Star, November 19, 1991.

- R. v. Munro, 1991 CarswellOnt 3290, 14 W.C.B. (2d) 636; R. v. Munro, 1991 CarswellOnt 2137.↩

- Interview of J. Nadelle for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Stephen Bindman, “Corruption trial of Liberal ex-minister becomes experiment in data processing,” Ottawa Citizen, January 14, 1991, p. A-3.↩

- Bindman, “Corruption trial.”↩

- R. v. Munro, 1991 CarswellOnt 3290, 14 W.C.B. (2d) 636, para. 74. ↩

- R. v. Munro, 1991 CarswellOnt 3290, 14 W.C.B. (2d) 636.↩

- Michael Davison, “Behind Munro’s legal Hell was an attack on native leadership,” Hamilton Spectator, November 22, 1991, p. A-7.↩

- Munro v. Canada, 11 O.R. (3d) 1; Gloria Galloway, “Munro legal tab hit $1.4M; Taxpayers on hook for $600,000 in extra interest, fees,” Hamilton Spectator, July 27, 1999, p. A1. ↩