Introduction

The Child-Saving Approach

Calls for Change

The Move to “Children’s Rights

A New Approach: Youth Criminal Justice

Conclusion

Introduction

The Police Magistrates’ Court in Toronto had the distinction, in 1894, of establishing the first known “Children’s Court” in North America.

[It] was not really a separate court, but we set apart a small room in the lower part of the City Hall, with a table and a few chairs, and I was accustomed to go down to that room to try all charges against children, in order to keep them out of the public court.

… If I felt that punishment was necessary, I would send the child to the Children’s Aid Society, or the Roman Catholic School for Children, for a few days, and give the culprits a scolding, and warn them to behave themselves in the future.

Police Magistrate Col. G.T. Denison[1]

It has been more than 120 years since this early attempt to treat young people accused of breaking the law differently than adult offenders. During this time, the Court’s approach to juvenile justice changed significantly. This was due, in large part, to three successive federal statutes, each premised on different values and objectives.

- The Juvenile Delinquents Act, enacted in 1908, gave judges broad discretion in imposing dispositions to “cure” children and youth of delinquency.

- The Young Offenders Act came into force in 1984. It shifted the focus from promoting young people’s welfare to protecting their rights, and from “curing” their condition to responding to their offending behaviour, while continuing to recognize their special needs.

- The Youth Criminal Justice Act – in force since 2003 – focuses on holding young offenders accountable by measures proportionate to their conduct. It reserves the most serious responses for the most egregious offences. For less serious matters, alternatives to courts and custody are the norm.

Juvenile justice was not the only area where major changes in the law have occurred, but it serves as an illuminating case study of how the Ontario Court of Justice and its predecessors chose to adapt to and participate in the development of changes.

Tony Doob, a professor of criminology and an expert in juvenile justice has described the changes as profound.

The story of how our laws dealing with the criminal behaviour of young persons have evolved over the past century is a fascinating one. The powers and responsibilities of judges changed dramatically: from being asked to find the solution a “good parent” would adopt to choosing a sentence that matched the seriousness of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the young person, while also being most likely to rehabilitate the young person.

This was a huge change that was brought about as a result of input from many groups, including judges. Judges made an important contribution through their decisions, their involvement in proposals for reform, and in their work with others to develop the programs and services they needed to do what the changing laws asked of them.[2]

The “Child-Saving” Approach

[A]s far as practicable every juvenile delinquent shall be treated, not as a criminal, but as a misdirected and misguided child, and one needing aid, encouragement, help and assistance.

Section 38, Juvenile Delinquents Act, 1929.

For most of the 19th century, Ontario’s police magistrates did not need to follow any special procedures when hearing cases of children accused of breaking the law. Children as young as age seven could be charged with criminal offences. They were tried in the same courts as adult offenders and subject to the same penalties.

Reformers who were part of what became known as the “child-saving” movement advocated a completely new approach, one that would treat young offenders not as criminals but as wayward children in need of care.

Two men led the crusade. J.J. Kelso was a newspaper reporter and Ontario’s first Superintendent of Neglected and Dependent Children. W.L. Scott was a lawyer and president of the Ottawa Children’s Aid Society. Under their leadership, the child-saving movement mounted an intensive lobbying and public relations campaign aimed at persuading parliament to enact comprehensive reforms.[3]

By the late 1800s, these efforts helped to create a broad consensus in Canada that children and youth in conflict with the law should: be tried in specialized courts; be incarcerated only as a last resort, and; if incarcerated, serve their sentences separately from adult offenders.

|

The First Children’s Court in North America J.J. Kelso had lobbied for a Children’s Court that would be “an educational rather than a police tribunal.” Toronto’s solution of hearing children’s cases in the basement of the Old City Hall courthouse was far from meeting that vision. It was, however, unlikely that any court could live up to Kelso’s ideals. In 1908, he wrote that the concept of a Children’s Court “stands for a loving, sympathetic and patient effort to win the child over to a recognition of the virtue of being good for its own sake, to awaken ambition, to inspire with high ideals, to stimulate growth in all that makes for manliness and good citizenship.” (Source: J. Kelso, “Children’s Courts” (1908), 28 Can. L. Times and Rev. p. 163.) |

The federal Parliament responded with the Act Respecting Arrest Trial and Imprisonment of Youthful Offenders in 1894[4] and the Juvenile Delinquents Act in 1908.[5]

A Separate Law for Kids:Juvenile Delinquents Act

The Juvenile Delinquents Act transformed the law for youthful offenders and the role of the courts hearing their cases. Unlike the Criminal Code, which specifies hundreds of distinct adult offences, the “JDA” created only one possible youth offence: delinquency.

In practice, a finding of delinquency was more akin to a diagnosis than being charged with an offence. This was made especially clear in a 1929 amendment which directed that a juvenile delinquent “shall be dealt with not as an offender, but as one in a condition of delinquency and therefore requiring help and guidance and proper supervision.”[6]

So broad was the definition of delinquency that courts could find a child to be a juvenile delinquent for virtually any bad behaviour.[7] In 1908, “juvenile delinquent” was defined as a child who violated any provision of the Criminal Code, or any federal or provincial statue or any municipal by-law for which a fine or imprisonment could be imposed, or who was “liable by reason of any other Act to be committed to an industrial school or juvenile reformatory.” In 1929, this was amended to include a child who was “guilty of sexual immorality or any similar form of vice.”[8]

The very broad definition of delinquency meant young people could be charged with offences that did not apply to adults. These so-called “status offences” included truancy (not attending school), incorrigibility (habitual disobedience), drug use, and sexual activity (even if entirely consensual).

Rather than pass sentence on a young person found to be delinquent, the judge would impose a “disposition.” Non-custodial dispositions ranged from a fine of up to $10 (increased to $25 in 1929), a suspended sentence, or placement in a foster home. Alternatively, the judge could commit the child to the care and custody of a probation officer, a children’s aid society, an industrial school, or a juvenile reformatory. All of these dispositions were available to the judge, no matter what behaviour led to the child being found to be delinquent.

Once found to be delinquent, children could be summoned back to the Court until they turned 21. On these return visits, the judge could again consider any of the dispositions in the Juvenile Delinquents Act. In theory, this power ended when children were “cured” of delinquency. In practice, juvenile offenders were often kept under the jurisdiction of the Court – and in many cases kept in custody – for longer periods that would have been imposed on adults sentenced for the same conduct under the Criminal Code.

The Creation of Juvenile Courts in Ontario

Juvenile Court proceedings were meant to be different from those in adult criminal courts. The Juvenile Delinquents Act stressed the need to separate children and youth from adults in pre-trial detention, at trial, and in post-trial incarceration. It also emphasized the need to preserve their privacy and avoid exposing them to stigma and public censure. Unlike adult criminal courts, juvenile proceedings could be held “in the private office of the judge or in some other private room in the courthouse or municipal building” from which the public could be excluded.[9]

The Court also had to ensure that the identity of the young person was kept confidential; the publication of any identifying characteristics was prohibited.[10] Proceedings were to be “as informal as the circumstances permit” and consistent with due regard for the proper administration of justice.[11]Juvenile accused did not have a guaranteed right to counsel, and lawyers rarely participated in the proceedings.[12]

After the JDA came into effect, a practical question for each province was where juvenile cases should be heard. In Ontario, An Act respecting Juvenile Courts was adopted in 1910.[13] It simply provided that every County or District Court Judge’s Criminal Court and every Police Magistrates’ Court would constitute a Juvenile Court.

Through the efforts of reformers Kelso and Scott, the Act respecting Juvenile Courts was passed in 1916 requiring that a Juvenile Court be created in every city, town and county in which the Juvenile Delinquents Act had been or would be proclaimed.[14] Judges appointed under the Act could, in turn, appoint probation officers to perform duties assigned by the judges; each had the powers of a police officer and a truant officer. The Act also provided for the establishment of Juvenile Court committees, consisting of probation officers and community volunteers, to assist judges in crafting dispositions.

Under the JDA, juveniles could be transferred to adult court if the offence charged was an indictable (that is, more serious) offence under the Criminal Code, and if the youth was actually or apparently at least 14 years old. The decision to transfer a youth to adult court was made by the presiding judge.[15]

There was initially no provision for an appeal from any decision of a Juvenile Court judge, whether that decision was to transfer an accused to adult court, find him or her to be delinquent, or to impose a particular disposition. That changed in 1929 when amendments allowed a provincial Superior Court judge to grant special leave to appeal any decision of the Juvenile Court on “special grounds.” A Juvenile Court decision could not, however, be set aside because of an informality or irregularity, as long as the decision appeared to be in the best interests of the child.[16]

In 1934, Ontario passed the Juvenile and Family Courts Act, adding family matters – such as child neglect and domestic relations – to the work of the Juvenile Courts, which became known as Juvenile and Family Courts.[17]

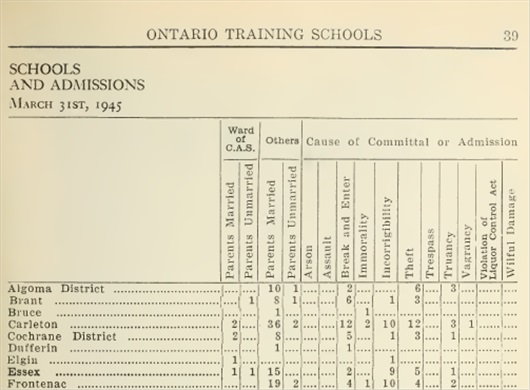

Widening the Net: Provincial Statutes and Training Schools

Ontario’s Juvenile Court judges had more than the federal Juvenile Delinquents Act to contend with. Provincial laws also came into play, often widening the net of children whose behaviour could bring them before the Court.

Offences under provincial statutes that applied only to children, such as truancy, fell within the definition of juvenile delinquency. As a result, truants and adolescents accused of other minor offences often found themselves in court as alleged juvenile delinquents. Otherwise, they could be dealt with as “children in need of protection” under the province’s child welfare legislation. The route they took into the system often depended on whether the Children’s Aid Society or the police were the first to become involved with them or their families.

Judges often also had to deal with a provincial statute called the Training Schools Act.[18] Under the Juvenile Delinquents Act, they could not order juvenile delinquents to be incarcerated in any place where adults could be imprisoned.[19] Judges could, however, commit the child to an “industrial school.”[20] This usually meant committal to a training school regulated by the provincial corrections ministry.

Although they were “schools” with the purpose of “training,” these facilities were also a form of incarceration. Upon admission, children became wards of the institution and the control of the parents or guardians was suspended.[21] Children could be returned by force if they tried to escape and it was an offence for anyone to shelter them.

[T]he word “prison” as defined in the Criminal Code includes an “industrial school,” a term commonly taken to mean training school…. Therefore, in law, training schools have a direct penal nature…. Committal to training school results in a very real deprivation of liberty and that fact is not changed by refusing to call it punishment or because the good of the child is the objective.

Karen Weiler, 1978[22]

Judges were often asked to make committal orders under section 8 or 9 of the Training Schools Act.

Under section 9, the judge could commit children between ages 12 and 16 years to a training school for offences punishable by imprisonment if committed by an adult. However, the judges did not have to stay within the limitations of this section. By relying instead on section 20 of the Juvenile Delinquents Act, they could commit children younger than 12 and for other offences.[23]

Section 8 of the Training Schools Act widened the net even further. Under that section, a parent or guardian could apply to the Court simply because they were “unable to control the child or to provide for his social, emotional or educational needs.” Section 8 created a whole new class of status offender: the “unmanageable” child.

Children as young as seven were brought before the Court under section 8. The Ministry of Correctional Services opened a special training school – the White Oaks facility in Hagersville – to care for wards under the age of 12 years.

“I was a young law professor trying to understand how these confidential proceedings worked,” George Thomson recalled. “In the late 60s, I wrote to Family Court judges across the province, asking if they could send me transcripts of cases where they had sent children to training school under section 8. I was amazed at how many I received. One judge sent me about 25 transcripts — none was more than 4-5 pages long. All it seemed to take to send a child to training school was a brief presentation from the Children’s Aid Society to the judge, indicating that a child had become unmanageable.”[24]

The broad definition of delinquency and the authority to bring unmanageable children to Court meant that children’s aid societies, treatment centres, and others had access to a process that could result in their wardship or guardianship role being transferred elsewhere. This became a source of frustration for some judges who felt the court process was being used inappropriately as a “dumping ground” for hard-to-serve children, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as Aboriginal youth and adolescent girls from poor families.

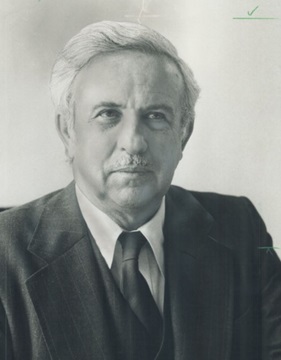

Profile of a Judge from the “Child-Saving” Era: Lorne Stewart

The “child saving” philosophy of the Juvenile Delinquents Act had an impact on the types of individuals who were seen as best suited for appointment to the Court to deal with these cases. Often they were non-lawyers, appointed because of their expertise in emerging professions such as social work or because they had experience in working with children and youth. Senior Judge Lorne Stewart was a prime example.[25]

“How are you going to help people in need?”

Victor Lorne Stewart was born on December 13, 1909 at South Mountain in Eastern Ontario. He grew up in Qu’Apelle, Saskatchewan where his father was a farmer. “As I got older I did a lot of farming. Pitched a lot of sheaths, and milked a lot of cows.” He studied both theology and psychology. The common denominator was, in his words, “How are you going to help people in need?”

He stayed out of school for a year and worked for the Big Brothers, “doing social work…This was in the slums of Toronto, Moss Park and so on. That was my territory. That is where I got to know what was happening to families, that is where I saw what was happening to kids. And I followed many of those cases into court, you know, unofficially, as a friend…” He also worked as a preacher in several small churches.

From the Air Force to the Court

Stewart became interested in delinquency and questions such as, “[W]hat kind of person should be helping families with their problems? Who has the knowledge, who has prepared themselves to sit down with people, where families are falling apart, and kids are raising hell?” He became such a person when, in 1944, he was appointed Chief Probation Officer for the City of Toronto and a Deputy Judge in Family Court.

His route to the bench was somewhat unusual. He had enlisted in the Chaplaincy Corps of the Royal Canadian Air Force where he spent two years in the Commonwealth training program at Paulson, Manitoba. His commanding officer said, “’Old Judge Mott is getting older and he needs help and all hell is breaking loose in Toronto with kids. All kinds of problems are coming up that they didn’t expect. And the authorities in Toronto have been after me to send Stewart back to Toronto. And he will be appointed as a Deputy Judge to work with Judge Harley S. Mott.’ So that became a tough decision, the war was just about over… and Mott said, ‘you have to come, we need you.’ So I came.”

In his role as Chief Probation Officer, Stewart “encouraged the policy of keeping cases out of Court if at all possible. Probation officers advised a lot of parents who had problems as to what to do… without going into Court. And I encouraged that.”

Stewart became a full judge (no longer a deputy) in 1952, Senior Judge of the Juvenile and Family Court of Metropolitan Toronto in 1964, and Senior Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) of the County of York when the Provincial Courts were created in 1968.

It is notable that Stewart moved up the judicial ladder despite his lack of legal training. He believed that legal expertise was important for a judge, but not enough on its own. “…I don’t think a legal degree is enough in the Family Court. I think it is important, and I don’t think any person should be appointed any more as a judge unless they do have a degree in law, but I think they have to have something else as well.”

Like a Father

Before Norris Weisman became a judge in 1975, he used to serve as a lawyer for Big Brothers. “I would go down to Family Court and represent families. This was before legal aid existed. Lorne Stewart, as a Family Court judge, was my hero. He would have the kids stand right smack in front of the dais and talk to them like a father. He had a touch with those kids. I modeled myself after him.”

Stewart was a key driver of the development of the 311 Jarvis courthouse, in what was then a low income part of Toronto. He referred to it as “the justice house where children and families were brought to mend, strengthened by those trained in care, skilled in the ways of law and in the human arts, a court brought together by separate paths leading to a single goal, to protect and cure, police, lawyers, social workers, psychologists and doctors, working together….”

Before retiring from the Court in 1976, Stewart was a member of the “Young Persons in Conflict with the Law” committee that produced proposals for reform of the Juvenile Delinquents Act in 1975. Later he became a senior research associate at the Centre of Criminology. He also worked for UNICEF and was involved with the drafting of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child.

| More Court or Clinic?

Judge James Felstiner was a long-time friend and one of many who regarded Stewart as a mentor. In a column that he wrote after Stewart’s death, one can sense their shared dismay about a growing emphasis on legal rights and punishment at the expense of helping kids. Here are excerpts from that column, published in 2002 in The Globe and Mail.In 1957, Metro Toronto Chairman Fred Gardiner and Judge Lorne Stewart succeeded in building an innovative comprehensive Juvenile and Family Court at 311 Jarvis St. in Toronto. The plaque in the building’s lobby states that the building was “…dedicated to the task of strengthening family life.” Lorne was forever proud of a newspaper’s description: “More clinic than court.” The court at 311 Jarvis concentrated on the needs of the children and families appearing there: probation, counselling, mediation and psychiatric services and the detention home for juveniles were all within the building. Lorne described the plan of the court this way: “The idea was to build a real team, working together, helping one another to solve problems.” But Lorne’s creation was gradually eroded over the years as concern with legal rights and calls for punishment displaced the concern for what you do to help the people appearing in court… I took my mentor back to see 311 Jarvis Street [in the late 1990s] when he was 88 years old. After seeing the children in handcuffs in court and the dirty, crowded, windowless steel cells in which the detained children are now held, tears started to come to his eyes and he asked me to take him home. Only after his death did I discover that he had written about that day: “What did I see – handcuffs, locked doors, more court than clinic.” His dream was no more. |

Calls for Change

Early Concerns About the Juvenile Delinquents Act

At the outset there was some opposition to the lack of due process protections in the JDA. When the bill was debated in the House of Commons in 1908, M.P. Edward Lancaster, an Ontario lawyer, expressed concern about the failure to provide for the protection and defence of children by counsel, with the result that they were “entirely at the mercy of a person called a probation officer” and deprived of the “inherent right to trial by jury.”[26]

When amendments were debated in 1929, Senator Wellington Willoughby, a lawyer from Saskatchewan, objected to a proposed provision – ultimately adopted – that would prevent certain decisions of a Juvenile Court from being set aside if they appeared to be in the best interests of the child. Senator Willoughby described the amendment as “most embarrassing to anybody practising law, and … hardly fair,” noting that “the interest of the child … is always a controversial question, and a matter of opinion.”[27]

Notwithstanding these concerns, the Juvenile Delinquents Act focus on the needs of the child as opposed to criminal accountability enjoyed wide support for over 40 years.

In the 1950s and 1960s, academics, judges and the media began to question a juvenile justice system that denied young persons the basic due process protections provided to adults.

Concerns included the wide discretion given to judges, the great disparity in sentencing for similar behaviour, and the open-ended, indeterminate nature of Juvenile Court dispositions. Simply put, the legislation was seen to authorize things to be done in the name of helping children that could never have be done in the name of punishing adults – an outcome argued to be at odds with the goal of ensuring that juvenile offenders were treated with leniency and compassion.

Catalysts for Change

In 1961, the federal Department of Justice established a committee to examine the juvenile justice system. In 1965, the committee released a report entitled Juvenile Delinquency in Canada. The report recommended more formal procedures and enhanced due process protections, including notice to the accused of the right to retain counsel and broader rights of appeal. It also called for stricter limitations on the exercise of court powers, more standardization of services and programs, better training for judges and other court officials, and mandatory pre-sentence reports.

Around the same time, the United States Supreme Court released two landmark decisions that greatly enhanced the due process rights of juvenile offenders.

The 1966 case of Kent v. United States involved a young person who had been transferred to adult court without a hearing. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the young person was entitled to: a hearing; access by his lawyer to the records considered by the Juvenile Court, and; reasons for the decision sufficient to enable a meaningful appeal. In the Court’s judgment, the “parens patriae” philosophy of viewing the state as a surrogate parent was “not an invitation to procedural arbitrariness.”[28]

This was followed in 1967 by In re Gault, a case in which a 15-year-old was found to be a delinquent because he had made a lewd telephone call. He was committed to a state industrial school until he turned 21 or was “sooner discharged by due process of law.” The U.S. Supreme Court held that children and their parents or guardians had the right to timely and specific notice of the proceedings. It also held that children were entitled to the same protection against self-incrimination as would be available to adults charged with a criminal offence. [29] The Court recognized that confinement to an industrial school was intended to be rehabilitative but, in reality, it was often a harsh environment.

Provincial Court Judges Add Their Voices

In 1968, Ontario’s Juvenile and Family Courts were subsumed into the new Provincial Court (Family Division). Before long, many family judges joined the chorus expressing concern about the state of the juvenile justice system.[30]

In the courtroom, some judges began to question the lack of due process for children and to resist the use of the Court for minor offences. They were particularly concerned about use of the Court process to deal with difficult children who were not true offenders but rather children in need of care and treatment.

“Many family judges took strong, principled positions in support of the children who appeared before them,” recalled Justice Rosalie Abella, a former Provincial Court family judge and a current member of the Supreme Court of Canada. Abella made early decisions in support of child representation and she joined other judges in taking a strong stand against the practice of bringing status offenders, such as truants, before the Provincial Court.[31]

Outside the courtroom, judges in many locations worked actively to develop programs in the community to assist them in making decisions about the youth before them and to reduce the use of training schools for kids who needed treatment as opposed to punishment. During the 1970s, the first diversion programs began to emerge with support from the federal government and leadership from Provincial Court judges. These programs were designed to find more effective out-of-court solutions for less serious offenders.

Consultation to Replace the Juvenile Delinquents Act

The process for replacing the Juvenile Delinquents Act with the Young Offenders Act stretched across almost 20 years. It included committee reports, proposed legislation, consultations and draft bills from successive federal governments.

Media criticism of the Juvenile Delinquents Act added to the debate.

The present legislation is swarming with injustice and absurdity. Children as young as seven years of age may be branded as delinquents, criminals; the law is capable of dragging children into Juvenile Court, not only for criminal behaviour, but also for what is vaguely referred to as ‘delinquent behavior’: school truancy, underage smoking, sexual promiscuity.

The Act denies children the right to a fair, unprejudiced trial on the discredited assumption that this is in their best interest, and it closes all Juvenile Court proceedings to the public. [32]

Near the end of the consultation process, Omer Archambault, a provincially appointed judge from Saskatchewan, was seconded to the federal Department of Justice to lead discussions with the judiciary. Ontario judges used this access to promote specific reforms. As an example, they successfully sought a provision requiring the judge’s approval before transferring young persons from secure to open custody or releasing them on probation.

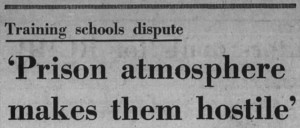

Concerns Intensify About Training Schools

In addition to the scrutiny being given to the Juvenile Delinquents Act, judges and others were becoming increasingly vocal about the shortcomings of the provincial Training Schools Act.

Karen Weiler, who later became a judge of the Ontario Court of Appeal, worked as a duty counsel in the Thunder Bay Provincial Court in the early 1970s. She became dismayed and disheartened by the number of young people being sent to training school by judges under section 8 of the Training Schools Act. “I felt very strongly [that children] shouldn’t be going there, especially as it was so far away. I always used to argue against the applications and usually lost.”[33]

With the help of two government corrections researchers who shared her concern about training schools, Weiler wrote a masters of law thesis that argued forcefully for reform. In a later article she wrote that, “the most frequent reasons cited by judges in their orders for committal were truancy, running away, and staying out late or overnight, but swearing, disobedience to parents, temper tantrums, and undesirable associations have also been given as reasons.”[34]

As was the case with the JDA, media concerns added to the debate.

|

| (Source: The Ottawa Journal, March 19, 1975.) |

In May 1975, the Ontario Legislature voted to repeal Section 8 of the Training Schools Act. Proclamation did not take place until January 1, 1977.

The Tragic Case of Norma Dean

Norma Dean was a 14-year-old who committed suicide while residing at an Ontario training school. Her tragic story illustrates the problem of using the Court as a safety valve or escape route when those caring for children consider them difficult to manage. It also highlights the frustrating circumstance a judge can face when no suitable facilities exist in which such a child can be placed.

Norma Dean had a history of emotional problems. On February 10, 1976, she became a voluntary patient at Thistletown Regional Centre, a treatment centre for emotionally disturbed children and adolescents. The staff there found her difficult to handle. She was aggressive, disruptive and would often run away.

One of Thistletown’s strategies for dealing with Norma was to bring her to court under the Juvenile Delinquents Act for minor offences committed within the institution. This occurred repeatedly, although it was not evident this approach was helping. She first appeared on a charge of assaulting a 15-year-old boy who had thrown a bible and called her names; another time for stealing $14 which she returned the next day.

Norma was back in court for having twice missed her curfew by one or two hours. That was not an offence but now that she had a record as a delinquent, Thistletown could bring her before a judge without a specific charge being laid. Norma was sentenced to one week in juvenile detention. The theory was that such a “short, sharp shock” might serve to alter a child’s behaviour.

On June 30, Norma had yet another court appearance – for breaking and entering. After having an argument with her mother when home for the weekend, she had broken back into Thistletown as she had nowhere else to go. Provincial Court Judge Stewart Fisher thought that Norma needed further treatment in a Ministry of Health facility. But Thistletown had decided it would not take her back and no other children’s mental health program was available. In the words of the Director of Thistletown, “What she needed was a closed setting, which we could not provide.”[35]

Having run out of options, Judge Fisher committed Norma under section 9 of the Training Schools Act. Her initial placement was at the Ministry of Correctional Services’ regional assessment centre. The judge’s recommendation was that they find an appropriate Ministry of Health treatment setting for her, rather than placing her in a training school on a long term basis.

I would think probably in my view that Norma should not go to a training school. I think that would be a bad mistake. I am not an expert in this area. But my feeling is that it would not be my recommendation that she should go to a training school at all.

From the verdict of Judge Stewart Fisher, July 7, 1976[36]

Once in the assessment centre, Norma became a training school ward.[37] That wardship enabled training school officials to decide where she should go next. Their decision was to send her, on a temporary basis, to the Kawaratha Lakes Training School in Lindsay, outside Peterborough, while waiting for a residential treatment bed to open up through the Ministry of Health.

Transferred to the training school on July 29, Norma was now located at a considerable distance from her mother – and the institution reduced visits by the mother to once a month. On August 20, 1976 Norma hanged herself in the closet of her room.

This tragedy only came to light two months later when an anonymous whistleblower drew it to the attention of Victor Malarek, a Globe and Mail reporter.[38] He would write a series of articles (and later a book chapter) about the case and the inquest held into Norma’s death, triggering an “emotionally charged debate” in the Ontario Legislature.[39]

In an interview, Judge Fisher spoke out strongly about what he perceived as the main cause of this tragedy.

Family Court Judge F. Stewart Fisher said he has been attempting to get the Ministry of Health to establish centres for emotionally disturbed children since he was appointed to the bench 3 ½ years ago, “but nobody seems to be listening”…. Judge Fisher said it is imperative that closed treatment centres for children with emotional problems be established with locked doors, but separate from centres for juvenile delinquents…. “No one person or one centre is responsible” for the death of Norma, he said. “It is a lack of resources.”

The Globe and Mail, October 29, 1976.

|

| (Source: Articles in The Globe and Mail on Oct. 29, Nov. 2 and Nov. 6, 1976. ) |

This case was seen as a tragic illustration of flaws in how children were moved from one part of the system to another. Much political debate ensued about the number and quality of treatment programs available for children like Norma Dean. This provided the primary impetus for a 1977 decision to unify government services for at-risk children and families within one ministry of the Ontario government. The new Children’s Services Division would be headed by George Thomson, then a judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division).

|

“In Need of Protection” This was the headline of an editorial in The Globe and Mail on December 16, 1977.

|

Over the next few years, the training schools were closed, a secure treatment program for youth was established with close judicial control over admission and length of stay, and child welfare laws were reformed to substantially increase the child welfare agencies’ accountability to the Court for decisions made about youth.

In addition, a large, government-funded program of child representation was established, now the Office of the Children’s Lawyer, giving judges the power to order that a child be provided with a lawyer in child protection cases.

Further, in the wake of the Norma Dean tragedy, the case to replace the Juvenile Delinquents Act – and to stop the practice of bringing children to court for minor matters – grew even stronger.

The Move to “Children’s Rights”

Due Process for Children: Young Offenders Act

After two decades of policy discussion and public debate about juvenile justice reform, the Young Offenders Act (“YOA”) replaced the Juvenile Delinquents Act, passing with the support of all parties in 1982 and coming into force on April 2, 1984.

As Tony Doob recalled, “The YOA attracted widespread support among both politicians and the judiciary because of the extent to which various proposals for reform had been made, challenged, and refined over the years. By the time the YOA came into effect, there were essentially no surprises.”[40]

Unlike the JDA, which allowed for provincial variation in age of Juvenile Court jurisdiction, the Young Offenders Act applied uniformly across Canada to all persons over age 12 and under 18 years of age. It eliminated “status offences,” which meant that youth could no longer be sanctioned simply for bad behaviour or for offences not applicable to adults. It also introduced due process rights and procedural safeguards not provided for in the Juvenile Delinquents Act.

The provisions included the right to counsel and definite, fixed-term sentences. These had long been features of adult criminal proceedings and were all the more strongly guaranteed with the advent of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms that had become part of the Canadian constitution in 1982.

The YOA also gave judges greater control over where youth would be placed (and for how long) once a decision was made to place them in a custodial setting.

Making the Adjustment

Many judges were excited about the new “rights-based approach” of the Young Offenders Act. Their main disappointment was that the new Act did not address the lack of community-based alternatives to training school, such as group homes and treatment programs.

Judge James Felstiner, among others, expressed concern that some of the benefits of the former “child saving” approach had been lost. Felstiner began his professional life as a social worker, one of the first to work with youth on the streets rather than in residential and institutional settings. He brought that experience – along with a Harvard law degree and masters of Social Work from the University of Toronto – to the Family Court in Metropolitan Toronto when he was appointed as a judge in 1970.[41]

In October 1985, Judge Felstiner authored an article setting out his observations of “practice and procedures under the Young Offenders Act.”

Procedures under JDA relied on the reasonableness and common sense of the judge and all others to proceed quickly to a fair and appropriate result. Under the YOA, we now rely on the detailed sections of the Act and Criminal Code. The pathway is often confused and tortuous. I have read again and again the comments praising the protection children have under YOA. In reality, I feel they have less. The long delays, costly procedures and restricted dispositions do not meet the needs of many children for quick and effective punishment, the needs for behaviour modification, acceptance of responsibility, increase in self-discipline, etc. While procedural legal rights are being protected, the overall benefit of YOA to the child, and therefore society, is of dubious value in my opinion.[42]

Still other Family Division judges saw the new approach as simply an evolution in the role of the judge. “There was a pendulum that swung back and forth when it came to being more focused on treatment or more concerned with holding youth accountable,” said Judge Norris Weisman. “I adjusted to it — that was my job.” [43]

Who Should Hear YOA Cases?

It was not obvious at first which division of the Provincial Court should function as the “Youth Court” under the new legislation. Previously, the Family Division heard cases against youth up to age 15, while the Criminal Division dealt with older offenders. Now that the maximum age of a “young offender” was 17, which Division should assume the Youth Court role?

The Ontario government had opposed the increase in the maximum age. It decided to keep the 16- and 17-year-olds under the jurisdiction of adult corrections system, although in separate facilities (or at least separate section of adult jails), while younger youth remained with the social services ministry. In keeping with this decision, both divisions of the Provincial Court had a role in young offender cases. The Criminal Division kept the older youth and the Family Division heard cases involving those age 12 to 15.

The decision by the Ontario government to leave 16 and 17 year olds in adult corrections, and to have the same criminal judges as before dealing with them as Youth Court judges, was for me the low point in implementing the new law. The Parliament of Canada, with support of all parties, had decided that the break between being a ‘youth’ and an ‘adult’ was to be the 18th birthday. Ontario appeared to be thumbing its nose at this decision. In terms of the administration of justice and the most serious punishment (imprisonment), it was going to change as little as possible.

Tony Doob[44]

To complicate matters, a Unified Family Court existed in Hamilton, established on a pilot basis as of 1977. This court – a Superior Court that included several former Provincial Court judges – had been hearing juvenile delinquency cases. Should proceedings under the new law remain there?

When the Unified Family Court expanded to new locations, Youth Court matters did not go with it and were removed from the Hamilton court. YOA cases remained a matter for the Provincial Court. Some saw this as an appropriate decision in light of the YOA’s criminal law focus. For others, it represented the loss of one of the goals of having a Unified Family Court because so many young offenders are also involved in child protection proceedings.

Nick Bala, a law professor at Queen’s University who has studied and written extensively about the youth justice system, made the following observation.

Ironically, one of the benefits that comes from not having a Unified Family Court in Toronto is that the Ontario Court of Justice there is able to deal more effectively with the many youth who straddle both systems.[45]

Profile of a Judge from the “Children’s Rights” Era: Lynn King

Over time, the “child-saving” philosophy of judges such as Lorne Stewart began to be replaced by an emphasis on respecting children’s rights. Lynn King was an example of a judge who believed passionately in due process for children and youth.

All in the Family

Originally from Sudbury, King practised law from 1973 until her 1986 appointment as a judge of the Provincial Court (later the Ontario Court of Justice). Her aunt and father, both former judges, attended her swearing-in ceremony.[46] The aunt – June Bernhard –had made history as the first woman to be appointed to sit in the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).[47]

Ted Andrews, Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) spoke at the ceremony about the ever-changing nature of the law that King would have to apply: “The law is constantly being reformed and no branch of law is more greatly affected than the courts dealing with families and children…. they are the very root of social change.”[48]

Why Kids Need Lawyers

She was in the vanguard of pushing for easy access [for youth] to expert [legal] representation.

Justice Brian Weagant[49]

Some of King’s reasons for believing strongly in the right of to counsel for young offenders are evoked in a 1997 newspaper article. It quotes her as “bemoaning the fact that recent cutbacks in legal aid have led to 65 per cent of family-law litigants appearing in court without lawyers…. She said it is no better in Youth Court, where a staggering number of teen-agers [without lawyers] unthinkingly agree to unrealistic or inappropriate bail conditions. They inevitably end up breaching them, she said, and are incarcerated until their trial date.”[50]

Using the Charter to Protect Children’s Rights

King’s judicial decisions underscored her strong belief in children’s rights. In 1991, she stayed (indefinitely postponed) mischief charges against three boys under the age of 16.[51]

The boys had been kept in “overcrowded, hot, dirty holding cells [in the basement of the courthouse at 311 Jarvis Street] for hours and taken to and from Court in handcuffs.” In King’s view, this treatment was humiliating, out of proportion, and insensitive to cases dealing with young persons. She found it to be cruel and unusual treatment, contrary to section 12 of the Charter.

She also found that the lack of privacy when talking to their lawyers in the holding cells violated the boys’ right to counsel under section 10(b) of the Charter.

In reference to this case, colleague Justice Brent Knazan was quoted: “She was completely fearless. She didn’t care what anybody thought, which is a great strength in a judge. ”[52]

Common Ground with “Child-Saving” Judges

Although they had different philosophical perspectives about children’s criminal behaviour, Lynn King and Lorne Stewart (profiled above) possessed a shared belief about how children should be treated in the courtroom. Both were seen as role models to other judges.

Lynn had a great feel for the young people before her. She engaged with them and took an interest in their lives. She spoke in very plain language. Her approach empowered the young persons and gave them a sense they were being heard and reinforced their sense of self-worth. I modeled a lot of my judging on it.

Justice Brian Scully[53]

King’s tenure as a Family and Youth Court judge was cut short by her death in 2005 at the age of 60. At a memorial event, Justice Marion Cohen spoke of her late colleague’s approach to young offenders in the courtroom.

Lynn by nature resisted authority and convention, but she did not judge from an ideological point of view. For Lynn, whether in the Youth Court or the Family Court, it was all about children…. No matter how horrendous the charge they were facing, Lynn always saw something smart and good in these children. She always called the accused by their first names, and she spoke to them and their parents in court. She wanted to know what school they went to, and what courses they liked, and who their teachers were.

Lynn believed that we had to do everything we could to keep young people out of the justice system because of the strong chance that we might, for no good reason, make their lives worse…

Lynn could never understand why we treat children as adults from the moment they step into Youth Court, and she could not bear to see children in the prisoner’s box. In the past year we sent a particularly large and obtrusive prisoner’s box back to the government because Lynn would not allow it to remain in the building.

A New Approach: Youth Criminal Justice

Concerns about the YOA

The Young Offenders Act accomplished many of the goals that had guided the effort, over many years, to replace the Juvenile Delinquents Act. It did not, however, end the debate about how best to respond to the criminal behaviour of young persons. For those who felt youth needed to be held more accountable, especially for more serious criminal behaviour, the sanctions available to the Court were regarded as insufficient.

By the late 1980s, the Young Offenders Act was subject to growing public and political criticism. Critics cited statistics showing that the number of youth charged with violent offences had risen steadily from 1986 to 1993. This led to amendments “toughening up” the Young Offenders Act in 1995.

Others argued that the growth in Youth Court charging rates was more a reflection of police charging practices and a general move to treating youth crime in the same way as adult criminal behaviour. A survey published by Professor Doob in 2001 conveyed a concern many Ontario Youth Court judges expressed about the numbers of youth being brought to court rather than being dealt with informally. Of the Ontario judges surveyed, 55% agreed that half or more of the cases that came before them could have been adequately dealt with outside of court.[54]

Concern was also voiced that custody was being overused. Although the numbers of youth in custody rose sharply after the YOA came into force, more than three-quarters of youth receiving custodial sentences under that Act had not committed violent offences.[55]

In the late 1990s, the federal Department of Justice reported that Canada had a higher rate of youth incarceration than many Western countries, including the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, with youth being incarcerated more often than adults tended to be for similar behaviour.

In 1998, the federal government released A Strategy for the Renewal of Youth Justice, advocating strong sanctions for violent behaviour. At the same time, it argued for much greater use of alternatives for the majority of young offenders who had not committed serious offences.[56] The stage was set for another transformation of youth justice – one that would have a major impact on the work of the Ontario Court of Justice.[57]

Proportionality: Youth Criminal Justice Act

The Youth Criminal Justice Act came into force in 2003.

The “YCJA” is premised on the principle that youthful offenders should be held accountable for their actions in ways that best facilitate their rehabilitation and reintegration into society. It holds that the most serious interventions should be reserved for the most serious crimes. Custodial sentences can only be imposed in specific circumstances, such as the commission of a violent offence.

Proportionate responses are encouraged by setting out criteria and requiring the judge to be explicit about why a non-custodial sentence would be inadequate.

The YCJA promotes avoidance of court and custodial sentences in many cases, expounding that “extrajudicial measures are often the most appropriate and effective way to address youth crime” and are “presumed to be adequate to hold a young person accountable” if he or she has committed a non-violent offence and has not previously been found guilty of an offence.[58]

The YCJA eliminates “transfers” of youth to adult court. Now youth remain in Youth Court, but the Crown may seek an adult sentence for the most serious offences.[59] If a youth sentence is deemed to be of sufficient length to hold the young person accountable, he or she is sentenced as a youth; otherwise, sentencing as an adult applies.[60]

In the view of Professor Bala, the YCJA “has done an excellent job of moving less serious offenders out of the Court. Those left are serious or repeat offenders who generally also have significant emotional, social and family difficulties. This is a huge challenge for the judges who hear these cases.”[61]

Preparing for the Change

The five years between the release of the government’s strategy in 1998 and proclamation of the new Act in 2003 provided an opportunity to prepare the youth justice system for the changes.

The fact that it was a new Act, not just a series of amendments, signalled a new direction. Judges took it very seriously, including the strong presumption against custody and the hurdles to be jumped before making a custody order.

Tony Doob[62]

It took several years for the proposals for reform to become the new Youth Criminal Justice Act. This meant that education on the directions proposed by the new law could begin early. In my mind the most important reason why the Act has had such a huge impact was the educational effort that produced what became a major cultural shift in all parts of the system.

Nick Bala[63]

The National Judicial Institute developed a comprehensive YCJA education program for judges. Convened over several days with a “train-the-trainers” component, it provided opportunities to apply the Act to simulated case situations. Later, programs were developed at the local court level across the country, including the Ontario Court of Justice.

|

Justice for Children and Youth Justice for Children and Youth is a specialized legal aid clinic in Ontario. It provides legal representation to low-income children and youth and advocates for legal and policy changes affecting them. Two judges of the Ontario Court of Justice – Marion Lane and Brian Weagant – are former executive directors of this organization. |

Other professionals such as police and probation officers also developed education programs. Thus, when the Act was proclaimed in 2003, the whole system was ready to move in the directions it promoted.[64] Indeed, even before the Act came into force, the Ontario Court of Justice – along with courts across Canada and other participants such as the police – anticipated the changes and began re-directing less serious offenders out of court. The number of young persons in custody subsequently declined dramatically under the new law and has remained low.

A Return to the Community

The YCJA includes provisions to curb the previous over-reliance on Youth Court and custodial sentences. Before launching judicial proceedings, police are required to consider whether it would be sufficient to take no further action, warn the young person, administer a caution or, with the consent of the young person, refer him or her to a community program or agency.[65]

The law promotes alternative measures (called extrajudicial measures in the Act), the use of innovative community-based programs, and ways of bringing together those involved in the life of the child to consider how best to respond to the criminal behaviour.

In many cases, young people must plead guilty to the offence before referral to a community program is possible. This is intended to ensure that there is a basis for intervening in the young person’s life. It creates a risk, however, that the young person will plead guilty without fully understanding his or her rights or the consequences of having a criminal record. This reinforces the need for good legal representation and for judges to have the skills and time to communicate well with the young people who appear before them.

The emphasis in the YCJA on community-based alternatives has led to judges adopting a pro-active role along with others in the community. The main purpose is to develop new programs or court processes for youth who might otherwise be placed in custody. In some ways, it resembles the activism of Provincial Court (Family Division) judges in the 1970s to develop community resources such as diversion programs and group homes.

Youth Mental Health Courts are an example of collaboration between the Court and the community. This initiative was pioneered in Ottawa and similar Courts now exist in several other communities as “problem-solving” resources for young offenders with mental health challenges. Certainly, nothing such as this was available in the ’70s when Norma Dean was rejected by her children’s mental health treatment centre and shifted to juvenile corrections.

Another example is the process put in place for urban Aboriginal youth in Toronto.

We have started an Aboriginal Youth Court here. It is a resolution court, a diversion court. Two days a month Justice Marion Cohen and I do this. We wear regular clothes, not gowns, and we sit at a table. We invite parents and guardians to the table. I am in a position of authority but I am there to support what the community is developing as a strategic plan for the young person.

Justice Brian Scully[66]

| Working with the Community: New Programs |

| The following are examples of programs involving judges of the Ontario Court of Justice which are intended to expand community solutions as envisaged by the Youth Criminal Justice Act. While not available in all Court locations, such innovations offer alternatives to Court and detention. |

| Peacebuilders Peacebuilders is a highly regarded restorative justice response to youth criminal behaviour. Young persons who acknowledge their guilt are referred to the program by a judge, defence counsel, or probation officer, generally out of a pre-trial conference. Each person is assessed and prepared for a circle gathering to develop a plan with others involved in his or her life. The program includes group meetings to discuss the participants’ conduct and how it affected their families and themselves. It includes a meeting with the victim or someone from the community who represents that role. The focus of the program, currently active in Toronto, is how to repair harm and restore confidence in the community. |

| Springboard While custody levels declined with the Youth Criminal Justice Act, pre-trial detention did not. Many youth are in pre-trial detention due to a failure to comply with conditions set by the Justice of the Peace when releasing them after arrest.Springboard is a community organization that helps to address this and other issues affecting youth age 12 to 17 who are involved in the criminal justice system. Its programs include:

|

| Diversion Programs Diversion programs existed long before the introduction of the YCJA, in keeping with the Act’s focus on diverting all but the most serious cases, they have grown in number and also expanded in scope. According to Darren Dougall from Kingston Youth Diversion, “[t]he focus is increasingly on the underlying issues behind the criminal behavior with mental health workers, restorative justice programs, intensive community support teams and even supportive housing.” |

| PACT Urban Peace Program PACT stands for “Participation, Acknowledgement, Commitment, and Transformation.” It is a community-based program that helps youth reach their potential through partnerships with the police, courts, probation, schools, and others. Among other approaches, it offers intensive probation by workers who know what it was like to be on the street. They provide intensive life-skills training and support to young people at risk of a future life of crime and imprisonment. |

| Youth Justice Committees The YCJA reintroduced the concept of Youth Justice Committees – bodies not unlike the Juvenile Court committees established in the early part of the 20th century under the Juvenile Delinquents Act. Youth Justice Committees are comprised of volunteers who develop community-based alternatives to formal court proceedings for youth who have committed relatively minor offences.While this concept has been used effectively in some court locations, such as Scarborough, Newmarket, and Sault-Ste. Marie, concerns about membership and role have meant it has not yet been implemented extensively elsewhere. |

| (Sources: Interviews of D. Dougall, and Justices B. Scully and D. Paulseth for the Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015; Springboard, PACT and Peacebuilders websites accessed April 2015.) |

Use of the Court for “Unmanageable Youth”

The YCJA did not deal with the challenge of youth appearing simultaneously before Youth Court and in child protection proceedings. Nor did it end the practice of the Court being used to move youth who are minor offenders but difficult to manage out of child welfare and into young offender programs. This is often done through “administration of justice offences” where the charge is failure to comply with an earlier order of the Court, such as a condition attached to a bail or probation order.

Youth involved in both the child welfare and youth justice system are known as “crossover kids.” Judges and others are developing a pilot project for crossover kids in four Ontario communities: Belleville, Chatham, Thunder Bay and Toronto. The goal is to ensure that such youth appear before the same judge in both matters, with resources available to enable the judge to find an integrated outcome that meets the child’s specific needs. This approach cannot, however, be implemented in jurisdictions with a Unified Family Court. That is because the UFCs deal with child welfare but not youth criminal justices cases.

The judges in my court see enormous value in being able to deal with what are called “crossover kids” in one court and ideally in front of one judge. The concept recognizes that child welfare is the long term plan; once someone is charged, the child welfare system shouldn’t just say, “Let the justice system take care of it. Both systems need to work together.”

Justice Brian Scully[67]

Conclusion

The role of the Court in “juvenile justice” has changed dramatically since children’s cases began to be heard in the basement of Toronto’s Old City Hall courthouse. The emphasis shifted with each of the three successive federal statutes, from “curing” delinquency, to protecting children’s rights, to an approach that emphasizes proportionality and community based responses.

Although the legal framework is certainly different than it was when the first delinquency law was introduced, many of the difficult questions that faced the first Juvenile Court judges remain.

- How to find the right balance between holding youth accountable and promoting their rehabilitation?

- How to avoid overuse of the Court, especially for youth who do not have the support of parents or community members?

- Which community-based programs are most effective and how can they be made more widely available?

- What are the best approaches for serious offenders who also have social and emotional challenges or addictions?

- How to ensure that youth placed in custody receive the treatment they need and are not subject to punitive measures?

- What kinds of court processes and alternatives to court are best suited to the range of needs demonstrated by young offenders?

Ontario judges have played an important role in the reforms and the efforts to find answers to these and other challenges. The story of how they have done so illustrates well how Ontario Court of Justice judges have learned to adapt to a world of continuous change.

- Denison Col G.T. Recollections of a Police Magistrate (Toronto: Musson, 1920), p. 254. ↩

- Interview of A. Doob for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015. ↩

- Department of Justice Canada, International Cooperation Group, The Evolution of Juvenile Justice in Canada, 2004, at p. 20.↩

- An Act respecting Arrest, Trial and Imprisonment of Youthful Offenders, 1894, 57-58 Vict., c. 58 (Can.). See description of features in Department of Justice Canada, International Cooperation Group, above, pp.18-19. ↩

- Juvenile Delinquents Act, 1908, 7-8 Edw. VII, c. 40 (Can.).↩

- Juvenile Delinquents Act 1929, 19-20 Geo. V, c. 46, s. 3(2) (Can.). ↩

- Doob, Anthony N. and Sprott, Jane B. “Youth Justice in Canada” (2004) 31 Crime and Justice 185, p. 187. ↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 2(g).↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 12(2).↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 12(3).↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 17(1).↩

- The participation of lawyers was viewed by some with suspicion if not outright hostility. Leon quotes correspondence between Kelso and Scott revealing that in crafting Juvenile Court procedure, Kelso would have taken “a firm stand on the exclusion of lawyers from the court.” Scott felt that a blanket exclusion might arouse opposition, but agreed that the appearance of lawyers should perhaps be limited to exceptional cases. (102, fn 212-213 and accompanying text). Leon, Jeffrey S. “Development of Canadian Juvenile Justice: A Background for Reform.”Osgoode Hall Law Journal 15.1 (1977): 71-106 at p. 102, fn 212-213 and accompanying text.↩

- 1910, 10 Edw. VII, c. 96, ss. 1 and 3 (Ont.).↩

- Leon, p. 101; 1916, 6 Geo. V, c. 54, s. 2 (Ont.).↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 9.↩

- JDA, 1929,s. 17(2).↩

- 24 Geo. V. c. 25 (Ont.).↩

- Training Schools Act replaced An Act respecting Industrial Schools, S.O., 1874, chapter 29.↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 26.↩

- JDA, 1929, s. 20(1)(i).↩

- Training Schools Act, s. 17.↩

- Weiler, Karen. “Unmanageable Children and Section 8” (1977-78), 8 Interchange 176, p. 177.↩

- Weiler Karen. “Unmanageable Children and Section 8”, p. 177.↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Sources for Profile of Lorne Stewart: Excerpts from transcript of L. Stewart interview for Oral History Project of the Osgoode Historical Society, courtesy of J. Felstiner; Interview of N. Weisman for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015; James Felstiner, “V. Lorne Stewart – Lives Lived,” The Globe and Mail (17 June 2002).↩

- House of Commons Debates, 18 July 1908, at 12402-05, quoted in Leon, p. 99.↩

- House of Commons Debates, 28 May 1929 at 298, quoted in Leon, p. 104.↩

- Kent v. United States (1966), 383 U.S. 541 at 554.↩

- In re Gault (1967), 387 U.S. 1.↩

- See e.g., “Child deserves right to be heard: judge,” The Globe and Mail (16 April 1973).↩

- Interview of R. Abella for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- “Secrecy, disorder, inertia,” Editorial, The Globe and Mail (3 November 1976).↩

- Interview of K. Weiler for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Weiler, Karen. “Unmanageable Children and Section 8”, at p. 178.↩

- Malarek, Victor. Gut Instinct: the making of an investigative journalist (Toronto: Macmillan Canada, 1996), p. 67.↩

- As reported by Lawrence Martin, “Bad mistake to move girl, judge warned,” The Globe and Mail (6 November 1976).↩

- By virtue of s. 17 of the Training Schools Act.↩

- Interview of C. Frid for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Malarek, p. 73; Ontario, Legislative Assembly, Official Report of Debates (Hansard), 30th Parl. 3rdSess, No. 102 (29 October 1976) at 4254-56.↩

- Interview of A. Doob for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of J. Felstiner for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Felstiner, James. “Some Observations of Practice & Procedures Under the Young Offenders Act”, in OAPSW METRONEWS, Special Features, October 1985.↩

- Interview of N. Weisman for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of A. Doob for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of N. Bala for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Callwood, June. “New woman judge finds courtroom crucible of social change,” The Globe and Mail (5 February 1986).↩

- “Women Judge Makes History”, Ottawa Journal (18 April 1979).↩

- Callwood, June. “New woman judge finds courtroom crucible of social change,” The Globe and Mail (5 February 1986).↩

- As quoted in Martin, Sandra. “Lynn King Jurist: 1944-2005,” The Globe and Mail (22 March 2005).↩

- Makin, Kirk. “Courts in tatters, judges say,” The Globe and Mail (17 November 1997).↩

- R. v. T.M., M.L. and J.H.(1991), 4 O.R. (3d) 203; 7 C.R. (4th) 55.↩

- Martin, Sandra. “Lynn King Jurist.”↩

- Interview of B. Scully for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Doob and Sprott, pp. 219-220.↩

- Interview of N. Bala for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Department of Justice Canada, A Strategy for the Renewal of Youth Justice. Ottawa: Department of Justice, Canada, 1998, cited in Doob and Sprott at p. 224; see also Caputo, Tullio and Vallée, Michel. “A Comparative Analysis of Youth Justice Approaches” Review of the Roots of Youth Violence Vol. 4: Research Papers (Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2008) p. 228, citing Hornick et al., 1996.↩

- In 1990, the Provincial Courts were replaced by the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), later renamed the Ontario Court of Justice.↩

- YCJA, S.C. 2002, c. 1, s. 4.↩

- YCJA, s. 64.↩

- YCJA, s. 72.↩

- Interview of N. Bala for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of A. Doob for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of N. Bala for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of N. Bala for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- YCJA, s. 6(1).↩

- Interview of B. Scully for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of B. Scully for Ontario Court of Justice History Project, 2015.↩