Introduction: An Evolving Court

1867-1967:The Magistrates' Era

1800s

1900s

1968-1989: The Provincial Courts Era

1968

1970s

1980s

1990-2015: The Integrated Court Era

1990s

2000 to 2015:The Ontario Court of Justice Era

Conclusion

Introduction: An Evolving Court

Throughout its history, the Ontario Court of Justice and its predecessors changed in fundamental ways. The work of the Court was profoundly affected by the enactment of various federal and Ontario statutes, the release of Supreme Court of Canada decisions, and the introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Judicial leadership drove other changes, from innovating education programs for judges and justices of the peace to renegotiating the Court’s relationship with government. Major structural reforms included the creation of Provincial Courts in 1968 (with two divisions and two chiefs) and their subsequent consolidation in 1990.

This essay chronicles transformative events in the Court’s history over a period of almost 150 years during four broad eras. Each of these eras is characterized by changes in the Court reflecting broader societal shifts. Cumulatively they illustrate the profound evolution of the Court from what it was in post-Confederation times to the modern Court of 2015.

1867-1967:The Magistrates’Era

1800s

A Province in the Dominion of Canada

The history of the Ontario Court of Justice can be said to formally begin on July 1, 1867, the date of Canadian Confederation. Although the Police Magistrates’ Courts pre-dated Confederation[1], their status as “provincial” courts began with the formation of the Dominion of Canada under two levels of government. As a province in this new nation, Ontario was empowered to make appointments to what were then called Police Magistrates’ Courts and other “lower courts” not specifically identified in section 96 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Appointments to the section 96 “superior courts” were to be made by the federal government. The Magistrates’ Courts and justices of the peace – along with the later formed Juvenile and Family Courts – eventually evolved into the Ontario Court of Justice.[2]

The First Criminal Code

The jurisdiction of the early police magistrates was fairly limited. That changed in July 1892 when the federal Parliament enacted Canada’s first Criminal Code. With the consent of the accused person, police magistrates could try many cases “summarily.” Without consent, they could try cases in large cities where the value of property stolen or received by false pretences did not exceed a total of $10.00. And they could try cases involving “disorderly houses” as well as all non-indictable offences. This was on top of the authority police magistrates had to try actions for breach of municipal bylaws or provincial statutes such as the Ontario Temperance Act[3].

The extension of the jurisdiction of Police Magistrates made by the Criminal Code [in 1892] has worked a revolution in the administration of criminal justice

in Ontario.

A Royal Commission Report on Ontario’s Police Magistrates, 1921, p.4.

1900s

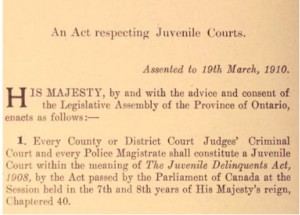

Juvenile and Family Courts

Juvenile Courts Act, 1910, 10 Edw. VII, c. 96 (Ont.). Ontario had no provincial juvenile or family courts until 1910, when the province enacted the Juvenile Courts Act[4] and police magistrates were constituted as Juvenile Courts. This followed from the Juvenile Delinquents Act[5]a federal statute allowing local authorities to establish courts to handle youth in conflict with the law along with adults who may have contributed to delinquency. In 1934, Ontario passed the Juvenile and Family Courts Act[6], adding family matters – such as child neglect and domestic relations – to the work of the Juvenile Courts.

Women on the Court

In 1921, an amendment to Ontario’s Police Magistrates Act allowed for women to be appointed as magistrates, but only in cities with populations of 100,000 or more and only where a resolution of the municipal council had declared that it was desirable for a woman to be appointed. Margaret Norris Patterson was appointed Ontario’s first woman magistrate the following year, presiding in the Toronto Women’s Court. By the late 1930s, Ontario no longer had any women serving as magistrates. There were, however, six female justices of the peace at that time.[7]

No More Police Courts

The early magistrates were known as “police magistrates.” They sat in “Police Courts,” often located in police stations. These magistrates (who heard criminal cases) were clearly not sufficiently independent of the police (who investigated the crimes). An important symbolic change took place in 1934 when legislation was modified to state that they would be known as Magistrates’ Courts instead of Police Courts.[8]

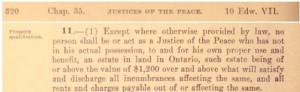

Changing Expectations for Justices of the Peace

Justices of the Peace Act, 1935, 25 Geo. V, c. 34 (Ont.), s. 7.For many years, justices of the peace were expected to be property owners selected from the so-called upper class, as was the tradition in England. Property ownership requirements were steadily reduced and then abolished in 1935 by amendments to the Justices of the Peace Act.[9]

Around the same time, justices of the peace ceased to have any trial functions, except when acting under the authority of a magistrate.[10]This was part of a change in which magistrates were given more jurisdiction and the role of justices of the peace became more limited.

Chief Judges and Magistrates

The concept of a judicial leadership structure began in 1922 with legislation specifying the designation of a senior magistrate for the City of Toronto, followed in 1936 by the authority to designate a senior magistrate in other districts.[11] The creation of “chief” positions did not take place until the 1960s. The position of Chief Magistrate was created in 1964 and filled by a succession of three individuals that year: Johnstone L. Roberts, F.W. Bartrem, and Arthur O. Klein. In the same year, provision was made for the appointment of a senior Juvenile and Family Court judge and an associate senior judge, wherever there was more than one judge of a Juvenile and Family Court. The position of Chief Judge of the Juvenile and Family Courts was created in 1968 and filled by Ted Andrews, shortly before these Courts and the Magistrates’ Courts were replaced by the “Provincial Courts.” The creation of these early leadership positions was the first step in fashioning a loose collection of judicial officers into a court.

Removal from Office

For many years, magistrates and justices of the peace held their offices “at pleasure,” meaning they could be removed from office when it suited the government of the day. In 1952, the Magistrates Act was amended to provide that a magistrate with two years’ or more experience could only be removed from office for cause – “for misbehaviour or for inability to perform his duties properly – and only after an inquiry conducted by one or more Supreme Court judges.”[12]The junior magistrates with less than two years’ experience continued to serve as “at pleasure” appointments. The situation was different for Juvenile and Family Court judges. Until the creation of the Provincial Courts in 1968, the tenure of these judges was dependent only upon good behaviour.[13]

1968-1989:The Provincial Courts Era

1968

Creation of Provincial Courts and Judicial Council

The creation of the Provincial Courts[14] was a transformative moment on the road to judicial leadership and independence of the provincial bench. The former Juvenile and Family Courts became the Provincial Courts (Family Division). The former Magistrates’ Courts and justices of the peace became the Provincial Courts (Criminal Division). Each magistrate and judge was appointed as a “Provincial Judge” and then informally assigned to one of the two divisions.[15]

Each Division had a Chief Judge. Ted Andrews served as Chief on the family side. He was a former “two hatter” who had done both criminal and family work in the previous system. On the criminal side, Fred Hayes replaced Arthur Klein as Chief Judge in 1972. In 1977, the Provincial Courts Act allowed for the appointment of an Associate Chief Judge in each division.

The Provincial Courts Act, 1968 created the first Judicial Council for provincial judges. Its purpose was to consider proposed judicial appointments and to inquire into complaints about judicial conduct. In addition to the two new chiefs, its members included the federally appointed Chief Justice of Ontario and Chief Justice of the High Court.

The Justices of the Peace Review Council – comparable to the Ontario Judicial Council – was created in 1974.[16]

1970s

Criminal Code Amendments

From the 1970s onward, an increasing number of indictable (more serious) offences have been reclassified as hybrid offences in the Criminal Code. For hybrid offences, the Crown can elect to proceed by way of “summary conviction,” in which case the trial will be held in the Ontario Court of Justice (formerly the Provincial Courts (Criminal Division)) rather than the Superior Court of Justice or its predecessors. For most charges involving hybrid offences, the Crown does indeed elect to proceed summarily. Hybridization has been accompanied by an increase in the maximum penalty available for certain offences where the Crown proceeds summarily. As a result of these changes, the Court has transitioned from handling predominantly minor criminal matters to a larger variety of more serious offences.[17]

Amendments to the Criminal Code on a variety of topics brought forth an entirely new spectrum of charges and defences.

Judge David Vanek[18]

Reclassification was not the only factor that led to the expansion of the criminal jurisdiction of provincial courts. Over time, a growing recognition of the criminal law expertise of provincial court judges across Canada saw a major shift in jurisdiction nationwide as accused persons charged with indictable offences increasingly chose (“elected”) to proceed in provincial court.

This shift also contributed to the increase in volume, seriousness and complexity of provincial court cases.[19]

Choosing the Ontario Court of Justice

Over a three-year period ending on March 31, 2001, 92 per cent of all accused persons who had an election as to the court of trial chose to proceed before the Ontario Court of Justice, as opposed to eight per cent in the Superior Court of Justice. Over the same period of time, 98.3 per cent of all criminal cases were resolved in the Ontario Court of Justice vs. 1.7 per cent in the Superior Court of Justice.

(Source: Webster, Cheryl Marie and Anthony N. Doob, The Superior/Provincial Criminal Court Distinction: Historical Anachronism or Empirical Reality?, Criminal Law Quarterly, 48, 2003, 77-109, at pp. 82, 83, 105-107.)

Formal Approaches to Judicial Education

In the early years of the Court, there was little, if any, formal education offered to judges or justices of the peace. For judges, that began changing in the 1970s. In 1974, for example, under Chief Judge Andrews, an annual education program was introduced for family judges. Chief Judge Hayes instituted programs for the Criminal Court judges. The programming was largely organized by the associations of criminal and family judges. The offices of the two Chief Judges prepared judicial handbooks, such as The Conduct of a Trial for criminal cases, and Reasons for Judgment for family law. Formal education programs for justices of the peace, however, were not instituted until many years later.

Unified Family Court

The Unified Family Court began as a pilot project in Hamilton in 1977. Legislation gave it jurisdiction over all family law matters, a jurisdiction which had previously been split between provincially and federally established courts. As a result, all family law cases in Hamilton were heard in a single court. The Unified Family Court was slowly expanded to other regions of the province in 1995 and 1999, and by 2015 covered about 40 per cent of Ontario’s population. Seventy-five per cent of the judges appointed to these newly-created Unified Family Courts came from the Ontario Court (Provincial Division).

In areas of the province without a Unified Family Court (now known as the Family Court of the Superior Court of Justice), the Ontario Court of Justice (the successor of the Provincial Division) has retained important family law jurisdiction, particularly in the area of child protection, for almost 60 per cent of the population.

The perception was that the creation of the Unified Family Court “pilot project” in Hamilton in the 1970s was the first step and the rest would be done in a few years: the family judges would be gone and the Ontario Court of Justice would just be a criminal bench.The UFC changed the dynamic within the Provincial Court. The family judges became fewer in number and our specific issues were not always addressed or understood. Therefore we could not operate as efficiently as we would have liked to. Nor were we able to get the resources we felt we needed. The emphasis was on the criminal work. This was due to the numbers and public and political pressures to address the criminal case backlog.

(Source: Input from provincial family judges for OCJ History Project, 2012.)

Family Law Reform

The 1970s were a time of legal reforms that changed the nature and complexity of cases before judges of the Provincial Courts (Family Division).

- The Court was given jurisdiction to conduct adoption proceedings.

- The oversight role of the Court was expanded in child protection proceedings.

- The Court was given the authority to require the appointment of lawyers for the children.

- The requirement to find someone at fault in spousal support proceedings was eliminated.

- Parents and guardians could no longer ask the Court to send a child to training school simply because their child was “unmanageable.”[20]

The 1970s was also a time when Family Court judges began working actively in their communities to create resources such as diversion programs, observation and detention facilities, and Family Court Clinics to provide better outcomes for children and families.

Demise of Trial De Novo

The demise of the “trial de novo” was seen as greatly enhancing the status of the Court.

Justice Brian Lennox, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice[21]

In the 1970s, most criminal trials in Provincial Court involved “summary conviction” offences as opposed to more serious “indictable” offences. Appeals from summary conviction trial decisions were heard by way of a new trial (“trial de novo”) in District Court.[22] The right to appeal was automatic. During each appeal, a District Court judge would hear evidence and arguments from both sides all over again, as if the Provincial Court trial had not occurred.

In the late 1970s, the “trial de novo” appeal was abolished.[23] Instead, summary conviction appeals (now to the Superior Court of Justice) are heard and judged on the basis of the existing record. The onus is on the appellant to demonstrate a serious error was committed by the trial judge. Where a new trial is ordered, the trial takes place in the Ontario Court of Justice (the successor of the Provincial Courts).[24]

End of the Grand Jury

In the 1970s, Ontario was one of the last provinces to have a grand jury system. In this system, the decision of a provincial judge presiding over a preliminary hearing for an indictable offence was not sufficient to send a criminal matter to trial before a federally appointed judge in District or High Court. After the preliminary hearing, the Crown Attorney was required to present essentially the same evidence heard by the preliminary hearing judge to a “grand jury” of lay persons. Without the grand jury’s agreement, the case could not proceed to trial. The elimination of the grand jury in the late 1970s meant that the decision of the provincial judge at a preliminary hearing would alone determine whether an accused person would have to stand trial.[25]

1980s

Justices of the Peace: Provincial Offences and Bail

The Provincial Court was profoundly changed on March 31, 1980 when

the Provincial Offences Act came into force. The Act simplified the process for prosecuting and enforcing offences in provincial statutes and regulations and municipal by-laws. The work of the justices of the peace changed dramatically as they presided over most provincial offence trials.

Until the mid-1980s, many bail hearings in Ontario were heard by Provincial Court judges. That began to change when bail hearings were assigned to those justices of the peace classified as “presiding.” There was no need to change legislation since the Criminal Code gives the power to hold bail hearings to “justices,” which includes justices of the peace. By the mid-1990s, Ontario justices of the peace were routinely appointed as “presiding” and therefore able to conduct bail hearings, except for those involving the most serious Criminal Code offences.

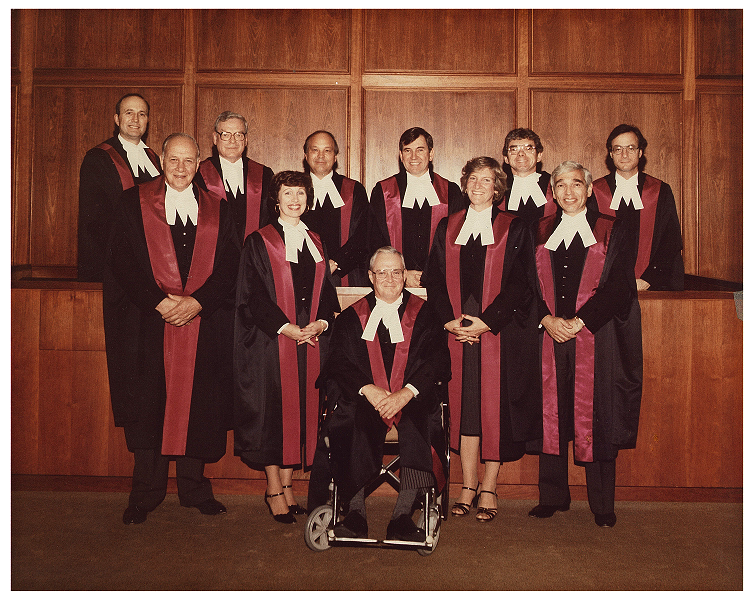

A Decade of Hearing Small Claims Court Cases

In 1980, the Provincial Court (Civil Division) was created. For ten years – from June 1980 until September 1990, there were accordingly three divisions of the Provincial Court: criminal, family, and civil. The Civil Division was introduced on a pilot basis in Metropolitan Toronto and then more broadly to hear Small Claims Court trials. Cases were heard by full-time Civil Division judges in areas where they had been appointed and by District Court judges or local lawyers serving as deputy judges in other parts of the province. In 1990, as part of a larger court reform project, the Small Claims Court function was transferred to the federally appointed court that later became known as the Superior Court of Justice. Although Superior Court judges can hear small claims cases, these cases are heard almost exclusively by deputy judges (lawyers who work on a part-time basis as Small Claims Court judges).

Small Claims Court Judges being sworn into Provincial Court in 1983. From left to right, back row: Ronald Radley, Gordon Chown, Stewart Kingstone, Ben Lamb, T. Charles Tierney, Marvin Zuker. From left to right, front row: Douglas Turner, Moira Caswell, Gerald Vickers, Pamela Thomson, Reuben Bromstein.

Legal Complexities: The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms, enacted in 1982 as part of the Constitution of Canada, guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it “…subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” In practical terms, this means that the Charter imposes limits on government interference with the rights and freedoms of Canadians. All laws passed by government must be consistent with the Charter and actions of the police and Crown must not violate the Charter rights of individuals. The Supreme Court of Canada has held that provincial courts have the power, in criminal trials, to refuse to apply legislation deemed inconsistent with the Charter, including the power to dismiss charges where the legislation itself violates the Charter.[26]

The Charter has changed the face of criminal justice in this country. No longer are individuals powerless to challenge state laws and actions that are supported by the majority. No longer are judges required to respect the choices of the executive or legislature when those choices violate fundamental societal values.

Justice Shaun Nakatsuru[27]

The Charter added to the complexity of the Court’s work.

What made the biggest difference to what I was doing was not the changes in the Court; it was the Charter. It required a major change in attitude that the judge had to bring to bear in the consideration of cases.

Justice Donald Dodds[28]

The Charter of 1982 forced the Court to a level of intellectual rigour and analysis that had before been virtually unknown in provincial courts, where previously the only real test of admissibility of evidence had been relevance.

Justice Brian Lennox, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice[29]

Valente Decision

Mr. Valente was charged with careless driving. In 1982, his lawyer questioned whether the Provincial Court was sufficiently independent to hear the case in light of Canada’s new Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Bill Sharpe, the Provincial Court judge assigned to the case, declined to hear it due to the independence challenge. The matter was appealed to the Ontario Court of Appeal and then to the Supreme Court of Canada. Ultimately, the Supreme Court decided that the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) was an independent tribunal within the meaning of s. 11(d) of the Charter. It identified the three essential elements of judicial independence as: security of tenure, financial security, and administrative or institutional independence. Valente was a key decision in a series of cases that led ultimately to the conclusion that judicial independence for all Canadian judges, whether they were provincially or federally appointed, was constitutionally protected.

Native Justices of the Peace

In his 1981 report to the Attorney General, law professor Alan Mewett’s vision included a training program to qualify native candidates for justice of the peace appointments.[30] Fred Hayes, Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) set out to make that vision a reality. Northern Ontario judge Gérald Michel and others were enlisted to develop the Native Justices of the Peace Program. The program, which began in the mid-1980s, featured an intensive pre-appointment education program. This enabled Aboriginal candidates to become justices of the peace, even though they may have lacked formal qualifications. The Native Justice of the Peace Program changed the face of the justices of the peace bench[31] and improved access to justice for Aboriginal communities. The program served as the basis for what has become extensive training for all new justices of the peace in Ontario – Aboriginal or not.

Requirement for Judges to be Lawyers

Those appointed magistrates and early Family Court judges were not required to be lawyers, and many were not. However, after the Provincial Courts were created in 1968, the practice was to appoint only lawyers with at least five years’ experience.[32] As of January 1, 1985, the Courts of Justice Act specified that new provincial judges be lawyers with a minimum of 10 years’ experience. This helped the Court to attract more highly qualified candidates. It was also a symbolically important change: recognizing the pivotal role performed by judges of the Provincial Court by imposing the same minimum eligibility requirement for appointment as federally appointed judges.

Young Offenders Act

The Young Offenders Act came into force in 1984, replacing the Juvenile Delinquents Act. This federal statute shifted the focus from promoting young people’s welfare to protecting their rights, and from “curing” delinquency to responding to their offending behaviour.

A New Way of Appointing Judges

In 1988, the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee was created to recommend judicial appointments to the Attorney General. Although it began as a pilot project, the Committee process has endured and was enshrined in legislation in 1995. The Committee is composed of a majority of public (non-lawyer) members and its process includes community outreach and interviews. The work of the Committee has been credited with depoliticizing the judicial appointment process and improving the quality and diversity of appointees, and has been a major factor in enhancing the reputation of the Court.

1990-2015:The Integrated Court Era

1990s

Ontario Court (Provincial Division)

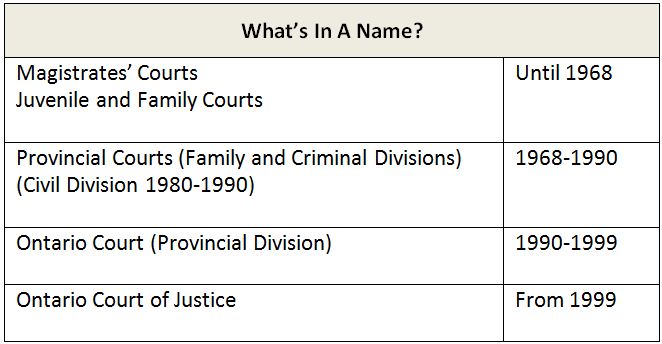

In 1990, the Provincial Courts (Family and Criminal Divisions) were replaced by the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), which became known simply as the Ontario Court of Justice in 1999. The formerly separate criminal and family benches, including all judges and justices of the peace, were consolidated to form a single court, although in practice, many judges continued to concentrate their work on either family or criminal cases.

The Chief Judge of the Provincial Division when the integration process began was Sidney B. Linden. Using the skeletal administrative structure set out in the Courts of Justice Act as a foundation, Linden built a strong judicial administration designed to outlive his term. Among other changes, he established the Chief Judge’s Executive Committee (CJEC) of Regional Senior Judges, creating a collaborative approach to judicial administration; secured staffing for the Office of the Chief Judge and to support the Regional Senior Judges; and provided ongoing training in judicial leadership for judges in management positions.

Early on, in order to associate the whole of the Court with his reforms, he invited the executive of the family and criminal judges’ associations to take part in CJEC meetings and decisions.

The creation in 1990 of what is now the Ontario Court of Justice and the appointment as Chief Judge of Sidney Linden, much contested at the time because he had not sat as a Provincial Court judge before his appointment as Chief, was a stroke of genius. Our administrative organization, our structure and our memorandum of understanding with government[33] are probably not sufficiently appreciated, but they have played a significant role in creating and maintaining an institutional independence recognized and envied throughout Canada at all levels of court.

Justice Brian Lennox, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice[34]

Backlog Crisis: The Askov Decision

The Askov decision – a criminal case that originated in Brampton – was released in 1990, shortly after the creation of the Provincial Division. In Askov, the Supreme Court of Canada defined a person’s right under the Charter to be tried within a reasonable time.[35] In Ontario, the result was to put in peril thousands of criminal cases, with a real risk of serious criminal cases being thrown out due to delays in bringing them to trial. The Court’s response was to develop a series of mechanisms, practices and strategies to tackle court delays. The new government at that time and Attorney General Howard Hampton increased the complement of the Court by 35 judges. With outreach from Hampton and the new Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee, those new appointments were much more diverse than before, especially in the numbers of women who joined the bench. The face of the Court was changing.

The Askov decision was ultimately of benefit by forcing the Court collectively to develop coherent approaches to dealing with backlog.

Justice Brian Lennox, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice[36]

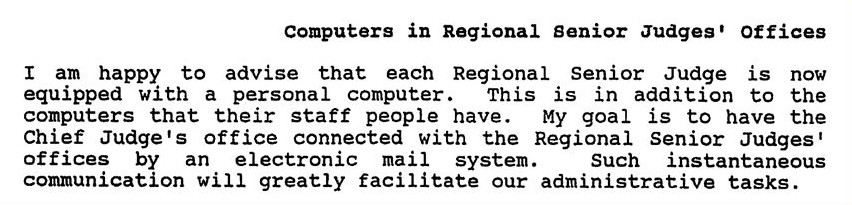

Computers and “Electronic Mail”

New technologies began changing the ways the Court worked. In the Chief Judge’s Newsletter of May 1991, Chief Judge Linden was happy to report that each Regional Senior Judge had been equipped with a personal computer. The goal was to connect Linden’s office with an “electronic mail system.” This was a modest but significant step in the introduction of technology to the Court.

Administrative Independence: Memorandum of Understanding

To ensure administrative independence from government, Chief Judge Linden negotiated a Memorandum of Understanding with the Attorney General. This Memorandum, signed in 1993, gave the Court control over its own budget and a degree of administrative autonomy that was unparalleled among trial courts in Canada. Under the MOU, the Office of the Chief Judge took over many responsibilities that had previously belonged to the Ministry of the Attorney General, including the administration of the judicial budget.

For decades prior to 1990… the Provincial Division of the Court was managed as if it was a small branch or division with the Attorney General’s Ministry….This agreement, for which there was no precedent, transferred many financial and management responsibilities from the Ministry to the Chief Judge.

Sidney Linden, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice[37]

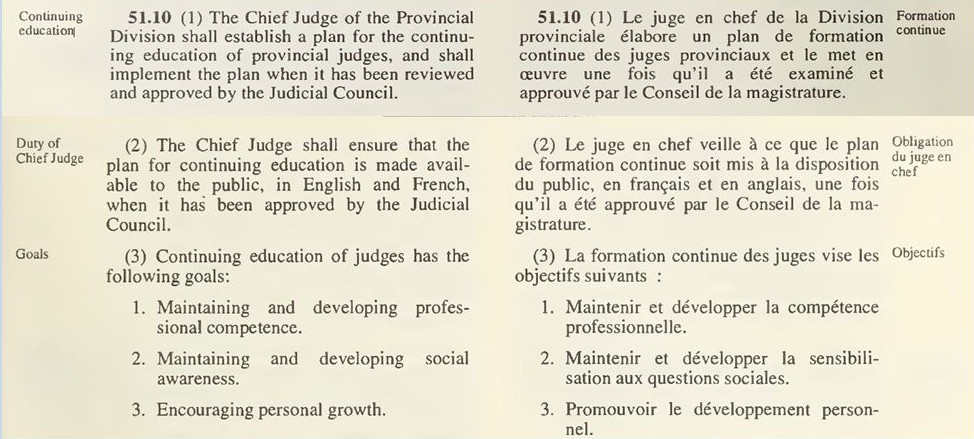

Requirement for Education Plans

A legislated commitment to formal judicial education for judges came into force in 1994 through changes to the Courts of Justice Act. In 2002, the Justices of the Peace Act was similarly amended to require a continuing education program for justices of the peace.

Independent Process to Set Judicial Salaries

Historically, provincially appointed judges had much lower salaries (and less prestige) than federally appointed judges. The financial gap was reduced after processes were introduced to determine judicial salaries and benefits. From 1979 to 1992, a three-person Provincial Courts Committee had been put in place – by agreement between the Ontario government and the judges’ associations – to make recommendations about judicial salaries and benefits.

On November 18, 1992, the government and the associations of the provincial Family and Criminal Court judges signed an historic Framework Agreement. As a result of that agreement, the Committee became known as the Provincial Judges’ Remuneration Commission and its recommendations regarding salaries and benefits became binding on government.

The existence of the Provincial Courts Committee and the Framework Agreement pre-dated by several years the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in the Provincial Judges Reference case[38] and served as examples of the foresight of the provincial judges’ associations in their stewardship of the judicial independence issue. The Framework Agreement was included as a schedule to the Courts of Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 1994.[39]

On November 18, 1992, the government and the associations of the provincial Family and Criminal Court judges signed an historic Framework Agreement. As a result of that agreement, the Committee became known as the Provincial Judges’ Remuneration Commission and its recommendations regarding salaries and benefits became binding on government.

The decision for the Commission to make binding decisions is a remarkable example of both the Provincial Court and government recognizing that financial security is a fundamental element of judicial independence. It brought to an end a difficult but enormously important struggle that stretched over a quarter of a century.

George Thomson, former Deputy Attorney General and former Provincial Court judge[40]

Conversion of Justices of the Peace

Before the implementation of the Justices of the Peace Act, 1989, many justices of the peace were paid by fees (“fee for service”) and worked part-time. The new legislation provided that justices of the peace were to work in full-time, salaried positions to avoid compromising their judicial independence. Beginning in the 1990s, the Court started “converting” justices of the peace to this new status. The full conversion was completed by 1998. This process has had a profound impact in increasing the professionalism of the bench.

Courts of Justice Act Amendments: Judicial Conduct

Initially, the Ontario Judicial Council was essentially controlled by federally appointed judges. It was also involved both in judicial appointments and in judicial discipline. Amendments to the Courts of Justice Act in 1994 changed both the role and the structure of the Council.[41] This included naming the Chief Judge of the Provincial Court as the Co-chair instead of simply serving as a member of the Council. The Council ceased to have a role in the judicial appointment process and focused on judicial discipline, investigating complaints of alleged misconduct against provincially appointed judges.

The 1994 amendments also authorized the Chief Judge to establish “standards of conduct for provincial judges.”[42] Chief Judge Linden created a Judicial Conduct Subcommittee to prepare Principles of Judicial Office in consultation with the judges’ associations and judges of the Court. The Ontario Judicial Council adopted Principles of Judicial Office in 1997 as the standard to govern judicial conduct and ethics in Ontario.[43] The Court also later adopted Ethical Principles for Judges, which had been prepared and adopted by the Canadian Judicial Council in 1998.

Principles of Judicial Office for Justices of the Peace came later, approved by the Justices of the Peace Review Council in 2007. The principles are identical to those for the judges, recognizing the important role of justices of the peace as judicial officers.[44]

Judicial Case Management

In the 1980s, criminal and family judges of the Provincial Court began to develop judicial case management systems to improve access to justice through early resolution and the establishment of time lines to avoid delays. A key element is the monitoring of cases by judges, individually or collectively. In the Family Court, the case management approach was enshrined in 1995 when the Office of the Chief Judge issued Case Management in the Family Court: A Guide to Implementation.[45]

The Judicial Case Management system made a huge difference to the way we do family cases. I was one of the resisters but once it came on board, it was phenomenal, although difficult for unrepresented people to manage. It was a seismic shift in opening up the way people got access to justice.

Justice Heather Katarynych[46]

The Rise of Problem-Solving Courts

In 1998, two “problem-solving” courts opened in Toronto. One was a Mental Health Court, established in May of that year. The other was a Drug Treatment Court, established in December. These Courts represented a departure in the handling of criminal charges for certain segments of the population and certain types of cases. In the 2000s, other problem-solving courts emerged, such as the Aboriginal (Gladue) Court and the Integrated Domestic Violence Court. In these courts, based on the principles of restorative justice, judges become more active in interacting with the parties and experts from the community to find solutions for vulnerable individuals, while protecting those who may be potential victims. During the 2000s, the numbers and types of problem-solving courts expanded across the province.

The Drug Treatment Court model represents a radical departure from the traditional role of a judge. In the Drug Treatment Court the judge becomes an active player, engaging in personal and direct dialogue with each Drug Court participant.

Justice Paul Bentley[47]

Transfer of Provincial Offences Act to Municipalities

Amendments to the Provincial Offences Act in 1998[48] transferred the responsibility for the administration of that Act – and revenues generated from it – from the province to the municipalities. Justices of the Peace hearing these cases remained part of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), but the administration was now provided at the municipal level.[49] The transfer led to an increased demand for justice of the peace services by municipalities and a corresponding increase in the justice of the peace complement within the Court.

2000 to 2015: The Ontario Court of Justice Era

Change of Names

As of April 19, 1999, the General Division, comprised of federally appointed judges, became the Superior Court of Justice and the Provincial Division became the Ontario Court of Justice. The title of provincially appointed judges became “Justice” instead of “Judge”.[50] The new title reflected a change in attitude towards the provincial bench, resulting from changes in the appointment process, qualifications for appointment, increased jurisdiction, as well as the widely recognized expertise of the Court.

There is a much greater respect for the provincial court judges now than when I started. This Court has some of the finest judges in the country.

Edward Greenspan, criminal defence lawyer[51]

Association of Ontario Judges

The Provincial Court in Ontario has always benefited from the existence, under various names, of strong associations of the judges of the Court, particularly in dealing with issues of judicial independence and judicial education. The judges’ associations have, since their creation, played a key role in the evolution of the Court. In 1994, Chief Judge Linden and the presidents of the Ontario Judges’ Association and the Ontario Family Judges’ Association signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) which recognized both the distinct and complementary roles of the Office of the Chief Judge and of the judges’ associations. The MOU underlined and formalized the positive, collaborative relationship existing between the two associations and the Chief Judge.

At the Annual Meeting of the Court in May 1999, the criminal and family judges associations merged into a single association of provincially appointed judges known as the Ontario Conference of Judges.[52] In 2015, they became known as the Association of Ontario Judges.

Education Secretariat

The 1994 Memorandum of Understanding between the associations and the Chief Judge formally recognized the Education Secretariat as the body responsible for overall education policy and funding associated with judicial training for the Court. The Education Secretariat was created by Chief Judge Sidney Linden in the early 1990s, with Judge Mary Hogan as its first chair. Composed of an equal number of representatives of the Chief Justice and of the Association of Ontario Judges, the role of the Secretariat is to coordinate the many education programs offered to the judges of the Court. It controls the education budget and is responsible for education policy, planning and presentation. The Secretariat works closely with the National Judicial Institute in presenting a range of judicial education programs. A similar approach to education was later taken for justices of the peace with the creation of the Advisory Committee on Education.

Youth Criminal Justice Act

The Youth Criminal Justice Act – a federal statute in force since 2003 – focuses on holding young offenders accountable by measures proportionate to their conduct. It reserves the most serious responses for the most egregious offences, providing sanctions akin to those imposed on adult offenders. For less serious matters which comprise the vast majority of youth crime, alternatives to courts and custody are the norm and the model is restorative and rehabilitative. The net result has been significant declines in the use of courts and custody for youth. This Act replaced the Young Offenders Act, and represents the second major transformation of juvenile justice since the Juvenile Delinquents Act of 1908.

Access to Justice Act: Transformation of the Justice of the Peace Bench

The Access to Justice Act, 2005 changed the justice of the peace system in Ontario, mandating the move to a bench of presiding justices. This statute formalized qualifications for appointment, created independent appointment and disciplinary processes, and formally recognized the office of Regional Senior Justice of the Peace. It also created a system whereby retired justices of the peace could remain available for assignment on a part-time (per diem) basis – similar to the situation already in place for retired judges.

Technology

Attempts at large-scale restructuring of court services through technology in the 1990s and 2000s were not successful. However, incremental changes have enabled the Court to improve service to the public. For example, in 2013, the Court initiated e-orders, a simple innovation that eliminated hours of waiting for documents. By installing a printer in the courtroom, a clerk can type the order, produce a hard copy, and hand it to the party concerned without delay. Videoconferencing has also had an impact, especially in northern locations.

You can’t fly people everywhere, but they can get to a video site. That gives access to people knowing what actually happened in court. That has been a big innovation.

Justice Peter Bishop[53]

Technology changed the way we make custody and access orders. The parents have to set up a new email account and that’s the way they have to communicate with each other about custody and access, and the judge gets to see everything they say to one another.

Consultation with family judges at 311 Jarvis Courthouse, Toronto[54]

Conclusion

The history of the Ontario Court of Justice began with the police magistrates and justices of the peace existing at the time of Confederation. Juvenile and Family Courts were added to the mix in the 1900s. In 1968, this collection of courts was folded into the Criminal and Family divisions of the new Provincial Courts. In 1990, the Provincial Courts were consolidated into the Ontario Court (Provincial Division), ultimately renamed Ontario Court of Justice in 1999. Along the way, the institution changed in many ways – including processes for appointing judges and justices of the peace, structures for judicial leadership and independence, and changes in the law affecting the volume and complexity of the cases.

We have come a long way since our courtrooms were in police stations, jails, basements of town halls, and furnace rooms of public libraries. Our Court has evolved from the most neglected in the province to one of the most significant and well-respected courts in the country.

Justice Annemarie Bonkalo, former Chief Justice, Ontario Court[55]

- According to a 1921 Royal Commission report on Ontario magistrates: “Police Magistrates appear to have been appointed first in Ontario under the provisions of the Municipal Corporations Act of Upper Canada, passed by the Parliament of Canada in 1849. This Act provided for the appointment of a Police Magistrate in each city or town upon the request of the Council.” W. D. Gregory, et al., Interim Report Respecting Police Magistrates of the Commission to Inquire into, Consider and Report upon the Best Mode of Selecting, Appointing and Remunerating Sheriffs, etc., etc., Printed by order of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, Toronto: Printed by Clarkson W. James, printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1921, (“1921 Magistrates Report”), p. 3.↩

- The Provincial Courts were created in 1968; they were replaced by the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division) in 1990, which in turn became known as the Ontario Court of Justice in 1999.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, pp. 3-4.↩

- Juvenile Courts Act,1910, 10 Edw. VII, c. 96 (Ont.).↩

- The Juvenile Delinquents Act,1908, 7-8 Edw. VII, c. 40 (Can.).↩

- Juvenile and Family Courts Act,1934 24 Geo. V, c. 25 (Ont.).↩

- Dorothy E. Chunn, Maternal Feminism, Legal Professionalism and Political Pragmatism: The Rise and Fall of Magistrate Margaret Patterson, 1922-1934, in Canadian Perspectives on Law and Society, Chapter VI, at pp. 110-111.↩

- The Magistrates Act, 1934, 24 Geo. V, c. 28 (Ont.), s. 2.↩

- Justices of the Peace Act, 1935, 25 Geo. V, c. 34 (Ont.), s. 7.↩

- T.G. Zuber, Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry, 1987, p. 23. (“Zuber Report”)↩

- Magistrates Act, 1922, 12-13 Geo. V, c. 48, s. 32; Magistrates Act, 1936, 1 Edw. VIII, c. 35 (Ont.), s. 5.↩

- Magistrates Act, s. 4; McRuer, J.C. Royal Commission into Civil Rights, Vol. 2 (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1968), p. 541. (“McRuer Report”).↩

- McRuer Report, p. 558. See also Juvenile and Family Courts Act, R.S.O. c. 201, s. 4(1), as amended by Ont. 1964, c. 51, s. 1(1).↩

- Provincial Courts Act, 1968, S.O. 1968, c. 103, ss. 14 (Criminal Division) and 17 (Family Division).↩

- Zuber Report, p. 27.↩

- The Justices of the Peace Amendment Act, 1973, S.O. 1973, c. 149, s. 3, in force on January 1, 1974.↩

- Interview of B. Lennox for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Vanek, David, Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge (The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History: 1999), p. 227.↩

- Interview of B. Lennox for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Under Section 8 of the Training Schools Act, a parent or guardian could apply to the Court simply because they were “unable to control the child or to provide for his social, emotional or educational needs.” In May 1975, the Ontario Legislature voted to repeal Section 8. Proclamation took place on January 1, 1977.↩

- Brian Lennox, Judicial Independence: Past, Present and Future: Judicial Independence and the Justice System, Remarks to Central West Regional Meeting of Judges, Burlington, November 25, 2014.↩

- References to “District Court” in this essay include the former District and County Courts which constituted one court under one chief judge.↩

- In very rare circumstances, an appeal can still be heard by way of trial de novo, but this remedy is now rarely sought and rarely granted. The party requesting the trial de novo must satisfy the appeal court that the interests of justice would be better served by a trial de novo than by an appeal on the record, either because of the condition of the trial record or for some other reason. For more information, see the section in this history entitled, “The Demise of the Trial de Novo.”↩

- Brian Lennox, Judicial Independence: Past, Present and Future: Judicial Independence and the Justice System, Remarks to Central West Regional Meeting of Judges, Burlington, November 25, 2014.↩

- Interview of B. Lennox for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- R. v. Big M Drug Mart, [1985] 1 S.C.R. 295.↩

- Excerpted from Justice Nakatsuru’s article concerning the Charter of Rights and Freedoms included as a “major change” in this history.↩

- Interview of D. Dodds for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Lennox, Judicial Independence Speech, November 25, 2014.↩

- Alan W. Mewett, Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on the Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario, Part II: Native Communities and Remote Areas, 1981.↩

- As of 2015, OCJ statistics indicate there were 29 native justices of the peace comprising 7.3 per cent of that bench.↩

- S.9(2) of the Provincial Courts Act, 1968 provided that the full array of judicial duties could be provided only by judges who had been members of the bar for at least five years or who had served for five years on the bench. This would explain the practice, after the creation of the Provincial Courts, of appointing only lawyers of five years’ standing. In the 1980s, Attorney General Roy McMurtry adopted the practice of appointing only lawyers with 10 or more years’ experience.↩

- See discussion of later in this section on “Administrative Independence: Memorandum of Understanding.”↩

- Lennox, Judicial Independence Speech, November 25, 2014.↩

- In R. v Askov, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 1199.↩

- Lennox,Judicial Independence Speech, November 25, 2014.↩

- Lennox,Chief Judge Sidney B. Linden, Where We Are, Where We’re Going!, Address to the Criminal Lawyers’ Association Spring Education Program, April 20, 1996, Toronto.↩

- Reference re Remuneration of Judges of the Provincial Court (P.E.I.), [1997] 3 S.C.R. 3. In order to protect judicial independence, this decision mandated the creation of independent remuneration committees for all courts.↩

- By a 1993 Order in Council (OR-407/93), the recommendations of the Provincial Judges’ Remuneration Commission were given the same force and effect as if enacted by the Legislature. The Framework Agreement became a schedule to the Courts of Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 1994, S.O. 1994, c. 12 s. 16. See also Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43, s. 51.13.↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Courts of Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 1994, S.O. 1994, c. 12 s. 16↩

- Courts of Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 1994, S.O. 1994, c. 12 s. 16; see also Courts of Justice Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. C.43, s. 51.9.↩

- Ontario Court of Justice, Biennial Report 2008/2009, p. 35↩

- Under section 13 of the Justices of the Peace Act, the Associate Chief Justice-Coordinator of Justices of the Peace obtained jurisdiction to establish standards of conduct for all justices of the peace in Ontario. This includes the authority to create a plan for bringing those standards into effect once they have been reviewed and approved by the Justices of the Peace Review Council.↩

- Judge Mary Jane Hatton and Judge Joseph C.M. James, editors, Case Management in the Family Court: A Guide to Implementation, issued by the office of the Chief Judge, Ontario Court (Provincial Division). At the Opening of the Courts, 1999, Chief Judge Linden said, “The Toronto Family Law judges at 311 Jarvis, deserve special recognition for the establishment of the original model of case management (in family law) and for its continued success and subsequent expansion to other Provincial Division locations throughout the province.”↩

- Interview of H. Katarynych for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Bentley, P. (2000). Canada’s first drug treatment court. Criminal Reports, 31, 257-271.↩

- Streamlining of Administration of Provincial Offences Act, S.O. 1998, c. 4, s. 2 [came into force on Royal Assent, June 11, 1998]. ↩

- Sidney Linden, Opening of Courts Speech, January 6, 1999.↩

- Courts Improvement Act, 1996, S.O. 1996, c. 23, Part IV, s. 8 [Note that this change only applied to the Chief, Associate Chief, and Associate Chief Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace]↩

- Interview of E. Greenspan for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Sidney B. Linden, Opening of the Courts Speech, January 6, 1999.↩

- Interview of P. Bishop for OCJ History Project, 2013.↩

- Consultation meeting at 311 Jarvis Courthouse, Toronto for OCJ History Project, 2012.↩

- Interview of A. Bonkalo for the OCJ History Project, prior to the end of her term as Chief Justice in 2015.↩