Magistrates’, Juvenile & Family Court: A Multiplicity of Courts

Introduction: A Multiplicity of Courts

Justices of the Peace

Magistrates – Criminal Court

Juvenile and Family Court Judges

Introduction: A Multiplicity of Courts

“The history of the Ontario courts shows that…it is a history of constant change and adaptation…The Ontario courts have survived because they have always adapted themselves to the needs of the people.” (The Honourable T.G. Zuber, Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry)[1]

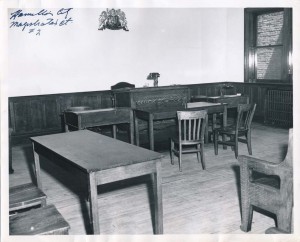

Opening the Doors on Magistrates’ Courts

The Magistrates’ Courts – although the busiest in the province – were often the most neglected. In 1951, a collection of photographs was taken in Magistrates’ Courts in a variety of locations around the province. The sorry state of these courtrooms, combined with the fact that many were situated within a police station, led Chief Justice James McRuer to write about Magistrates’ Courts in 1968: “One cannot come to any other conclusion than that those responsible have no concept of the elementary rights of accused persons and witnesses who may attend trials, and the rights of the public, to have justice administered with dignity and in circumstances that convey a respect for the law.”

Here is a sampling of what magistrates’ courtrooms looked like in 1951:

(McRuer, J.C. Royal Commission Inquiry Into Civil Rights. Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1968. Vol. 2, p. 539. All photos courtesy of the Law Society of Upper Canada Archives.)

The modern Ontario Court of Justice is presided over by judges and justices of the peace appointed by the provincial government. It is distinct from other courts in Ontario whose judges are appointed by the federal government.

The story of the Ontario Court of Justice can be said to begin at Confederation on July 1, 1867. This is when the Canadian constitution came into force, dividing jurisdiction between the federal and provincial levels of government, including the province of Upper Canada which later became Ontario.

From 1867 to 1967, the collection of courts that would ultimately become the Ontario Court of Justice grew in a haphazard manner to form a patchwork system of courts across the province. The evolution of these courts can be directly traced through the history of the province itself – shaped by social and political developments, population growth, technological changes and urbanization.

At the time of Confederation, Ontario had a system of trial courts that included superior, district and county courts, together with a system of local courts. In the superior, district and county courts, legally trained judges dealt with the most serious criminal and civil matters.[2] Less–serious criminal offences, provincial offences and municipal by-law infractions, and small civil disputes were heard by local courts – often called the “lower” or “inferior” courts – presided over by magistrates and justices of the peace.

In the early years, almost all judicial officers of the local courts were lay (“non-lawyer”) members of the public and were concerned solely with disputes over property and crime.[3] Gradually, they began to acquire jurisdiction over matters involving children, juveniles and families. Together, the local juvenile, family and criminal courts ultimately evolved into the Ontario Court of Justice.

For most members of the public, the only image of the administration of justice is what they found in the local courts.[4] As Magistrate J.R.H. Kirkpatrick recalled in 1962: “More people see them in action than any other of all our courts.”[5] Before 1968, the local courts included justices of the peace courts, police courts, magistrates’ courts, juvenile courts, family courts and small claims courts. Some were established and funded by municipalities, others by the province. Not all of these courts were in existence at the same time. Not every type of court was found in every jurisdiction throughout Ontario. Despite this confusing mishmash, these courts were the places where the public met the justice system.

It was in these courts that cases involving trespass, thefts, common assaults, loitering, traffic offences and municipal by-laws — to name a few — were heard. Neglected children, young people charged with delinquency, and deserted wives also had their cases heard here. These courts tended to be poorly funded and housed in inadequate and inappropriate accommodations, such as town halls, jails and police stations.

While the English court system served as the prototype, the Ontario system slowly changed to reflect the nature, geography and the people of the province. Yet, despite the changes they endured, the collection of local courts remained the busiest — and most neglected — in the province.[6] The issue of neglect — and the possible reasons for it — should not be ignored. “Individuals with low income and low social status” made up most of the people who came before these courts. The higher “superior” courts were involved with adjudicating disputes about property and civil rights of the middle and upper classes. “If members of these classes had been more involved as litigants in the lower criminal courts, it is unlikely that their shoddy and unjudicial conditions would have been tolerated for so long,” [7] wrote renowned political scientist, Peter Russell.

In 1968, the local courts – except for those dealing with small civil lawsuits — were amalgamated into the new Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and Provincial Court (Family Division). Then began a new era in the history of the Ontario Court of Justice.

Given the complicated evolution of the local courts from 1867 to 1967, their stories are best told through the three types of judicial officers who presided in them – the justice of the peace, the magistrate and the juvenile and family court judge. And to make a confusing story even more confusing, one person often acted in all three of these roles!

The Constitution and the Courts

On July 1, 1867, the Constitution Act, 1867 – originally called the British North America Act (BNA Act) – enacted by the British Parliament took effect to create the Dominion of Canada and bring about Confederation. The new Dominion was divided into four provinces: Ontario (Upper Canada), Quebec (Lower Canada), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The new constitution gave certain powers to the federal government, others to the provincial governments. The structure of courts in the provinces is the product of the division of powers in the constitution.

The Fathers of Confederation of the Quebec Conference, October 1864, who drafted the basic plan for the federal union of Canada. The original of this famous painting by Robert Harris was destroyed in the 1916 Parliament buildings fire. (Library and Archives Canada, accession number 1989-565 CPA, item 90)

The Constitution Act, 1867 made the establishment and administration of most courts a provincial responsibility. Those powers include the constitution, maintenance, and organization of provincial courts both of civil and criminal jurisdiction (s. 92(14)). However, the province did not have the power to appoint all judicial officers to all the courts it administered. The federal government was given the power to appoint judges of a province’s superior, district or county court (s. 96). Further, the federal government was given exclusive jurisdiction over both criminal law and procedure (s. 91(24)).

The effect of this jurisdictional division is that the provinces establish the courts that administer the federal criminal law. But, in the case of courts outside of s. 96, the provinces have the power to appoint judges and justices of the peace. To further complicate matters, the province and municipalities can create offences — so long as they are not criminal offences — in aid of the enforcement of laws enacted within legislative jurisdictions. These are “provincial offences” and “municipal by-law infractions.”

Justices of the Peace

Introduction

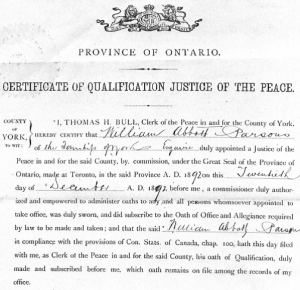

William Abbott Parsons,

Justice of the Peace

In 1892, one William Abbott Parsons, Esquire was “duly appointed a Justice of the Peace” for the County of York. A local farmer, Parsons was the ideal candidate – he could and did file his “oath of qualification” on December 20, 1892, swearing that he met the minimum standards, at the time, of landownership required to be a justice of the peace.

The office of justice of the peace was imported into Canada in 1763 together with all the laws of England, both civil and criminal.[8] At that time, the justice of the peace possessed “great powers and authority” in the judicial system, including trials of nearly all serious criminal offences.[9] By degrees, those powers were taken over by magistrates and legally trained judges.

In the early 1800s, justices of the peace were “creatures of necessity.”[10] The country was sparsely settled, it was difficult to travel around, and legally trained individuals were a rare commodity. A centralized and organized court system was an impossibility, both practically and financially. The solution? The introduction of the justice of the peace – a local person who typically had no legal training.

At the time of Confederation, Ontario justices of the peace continued to have extensive powers in minor criminal matters, dating back to 1800 when the Legislature of Upper Canada adopted the criminal law of England as it stood in 1792.[11] Ontario’s Lieutenant Governor assumed the responsibility for appointing justices of the peace in 1868.[12]

By 1967, a hundred years later, the powers of the justice of the peace had been significantly limited to taking “informations,”[13] issuing warrants, granting bail and presiding at the trials of summary offences.[14] This evolution was tied to the urbanization of the province. As villages grew into towns and cities, justices of the peace saw their jurisdiction diminish.

The Origins of the Office

The position of justice of the peace originated in England. In fourteenth century England, justices of the peace were selected from among the “most worthy” persons in their counties[15] or the “most sufficient knights, esquires and gentlemen of the land.”[16] In the fifteenth century another qualification was added: they also had to be landowners.[17]

Importing the image of the “landed gentry” or “country squire” into the rough-hewn back country of Ontario proved to be an “impossible aim.”[18] At the time of Confederation, Ontario justices of the peace were to be the “most sufficient persons, dwelling in the…district” and they were also to be landowners.[19]

Finding people in the wilds of the province who could fill these property requirements – and had any understanding of the law – proved to be a challenge. As a result, several Qualifications Acts were enacted in the late 1800s which cancelled commissions of unqualified justices of the peace who didn’t meet the minimum standards of land ownership.[20] Gradually, the requirements became less stringent and, in The Justices of the Peace Act, 1935, all references to minimum property qualifications were repealed.[21]

The Challenges of the Office

Despite attempts to exercise some sort of control over the office, the justices of the peace were not administratively organized and functioned largely independently.

By 1934, the appointments process was out of control. Some 10,000 justices of the peace were on the rolls at that time. The attorney general of the day, Arthur Roebuck, dismissed them all by order-in-council, reappointing only 243.[22]

An inquiry conducted by the Honourable James McRuer — then Chief Justice of the High Court for Ontario — in 1968 revealed the names of 925 justices of the peace on “incomplete records but we are informed that in addition an unknown number whose names are not officially recorded anywhere…We have been unable to determine how many justices of the peace there are in Ontario.”[23]

How did this happen? According to McRuer, the appointments process devolved into a “comic opera title system that can only be described in no more appropriate language than ‘just silly.’”[24] Appointments to the office were political rewards by the provincial governments of the day — often bearing no relationship to the ability or skill of the appointee to carry out the work of the position.[25]

The dignity and reputation of the office was further compromised by a near complete lack of training for justices of the peace. Wrote one justice of the peace in 1968:

“After my appointment, I found it extremely difficult to acquire knowledge of my duties, and because of lack of instruction, I wandered along learning by trial and error. The only books I could find were about English J.P.’s which were of little use in our country. It is my hope to attend lectures or courses of instruction, and I would gladly attend at my own expense, or even just be recommended books that I may study to enable me to perform more efficiently.”[26]

The “Fee” System

In the early days, very few justices of the peace were paid salaries. The vast majority were paid on a “fee for service” basis.[27] The fees were assessed against convicted persons. This meant that if a person was convicted, he or she paid a fee to the justice of the peace. If there was no conviction, the justice of the peace did not receive a fee.[28]

As McRuer explained in his report: “The fee system is a real inducement to justices of the peace to curry favour with police officers in order to ‘get business.’”[29] At that time, one justice of the peace wrote:

“The position of Justice of the Peace has no security because it depends upon keeping the goodwill of police officers if he or she is to continue processing their summonses. I feel that we could perform our old time function of protecting the rights of accused persons if we were made independent by being paid a salary.”[30]

A Widely Criticized Office

By the late 1960s, the flaws in the structure of the office of the justice of the peace were readily apparent. An office that was intended to stand as a safeguard of the civil rights of the individual against the exercise of arbitrary police power was criticized as being “little more than a sham.”[31]

The appointments process was highly politicized. The payment arrangements led to justices of the peace being too close to the police, which detracted from the independence of the office. Justices of the peace were not organized or managed. They were not trained for their work. Substantial change was required to ensure public respect for law and order. That change was coming.

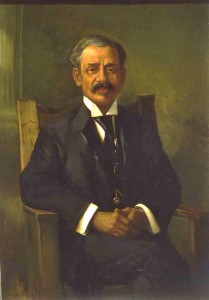

William Peyton Hubbard, Justice of the Peace

William Peyton Hubbard was appointed a “Justice of the Peace in and for the County of York” in 1908. His appointment was a typical one for the time. Hubbard had served as an alderman in the City of Toronto — on and off — since 1894. In addition, as chairman of a special committee, he spearheaded an effort to introduce provincial legislation enabling the city to generate, produce, lease and develop hydro-electric power — this led to the establishment of the Toronto Electric Hydro system. When Hubbard’s bid for re-election failed in 1907 — probably as a result of his support for the hydro system, which was roundly condemned in many quarters — he received an appointment as a justice of the peace and served in that position for six years until his re-election as an alderman in 1913.

Looking at this story, it is uneventful in many respects until one factors in a key detail. Hubbard was a black man. He was born near Bloor and Bathurst streets in Toronto in 1842, the son of freed slaves from Virginia. After leaving school, Hubbard worked as a liveryman and, later, a driver for George Brown, a publisher of The Toronto Globe (now The Globe and Mail newspaper.)

So the story goes, it was George Brown, impressed by Hubbard, who suggested he enter public life. A search of the newspapers of the day reveals references to the fact that Hubbard was the city’s first black alderman and the County of York’s first black justice of the peace. When a portrait of Hubbard was unveiled in 1913, commemorating his many years of public service, he was called “the true civic spirit” and complimented for being a “credit to the city, to the country and to the race from which he has sprung.” (The Toronto Daily Star, November 7, 1913)

Magistrates – Criminal Courts

Introduction

“I am independent of everyone.”

(Police Magistrate George T. Denison in Recollections of a Police Magistrate, 1920.)

The evolution and expansion of the office of magistrate — like that of the justice of the peace — was fuelled by the urbanization of the province from 1867 to 1967. Interestingly, this office too was plagued by a lack of independence, training, and organization. But, unlike the justices of the peace, magistrates expanded their powers. By the mid-1960s, virtually all criminal offences — from the most minor to the most serious — were heard in magistrates’ courts.[32]

The office of magistrate in Ontario dates back to 1849, when The Municipal Corporations Act established a Police Office in each town listed in a schedule to the act and directed the police magistrate of that town ‘to attend daily, or at such times and for such period as shall be necessary for the disposal of the business to be brought before him as a Justice of the Peace…”[33] In this way, the police magistrate began gradually assuming the role previously the domain of the “country squire” justice of the peace. Magistrates, like justices of the peace, were appointed by the province.[34]

“I refused, as I have said, to act as president or director of any company, and I am pleased to see that of late years provision has been made by statute preventing judges from accepting any such offices. Such legislation should not have been necessary, but the practice at one time was a common one. I also decided to take no fees. I have a great aversion to the fee system; in time, it is sure to bring the pendulum off plumb. A man acting in a judicial capacity should have nothing to affect him, pecuniary or otherwise, in deciding either way.”(Police Magistrate George T. Denison in Recollections of a Police Magistrate, p. 5.)

Police Courts – Police Magistrates

By the late 1800s, legislation provided that there should be a police magistrate in each Ontario city and town where the population exceeded 5,000. In certain conditions a police magistrate might also be installed in smaller towns and counties. The legislation introduced the terms “police magistrates” sitting in “police courts.”[35] There is no doubt these courts intermeshed judicial and police functions – a direct challenge to maintaining any sort of real judicial independence.

“I am independent of everyone.” So wrote Colonel George T. Denison in his 1920 memoir, Recollections of a Police Magistrate.[36] He came to the office with a strong understanding of the need for judicial independence, in the sense of not owing any favours or accepting any fees.

Sworn in as a magistrate in 1877, Denison wrote with pride about not taking any “favours”:

“Very soon after my appointment I received season passes on the Ontario railways, and on steamboat lines, etc. I sent them all back politely explaining that formerly I would have been glad to receive them, but that I had recently been appointed Police Magistrate and could not accept them. This policy has been a great satisfaction to me ever since…I am constantly trying cases between the great railways companies, and citizens, thieves, and trespassers, and I am just as independent of the great railway companies, who can and do influence both the Dominion and Provincial Governments, as I am of the poor tramp who is found trespassing on their lines, or stealing a ride.”[37]

“Police Courts”

“It does not help to educate (the public) to see prosecutions handled by police officers, members of the same force that brought about their arrest or summons to court and who, it is widely thought, have a deep and abiding interest in an accused’s conviction. Nor does it impress them with the integrity and independence of the court; they have often heard that ‘your word is never as good as a cops’, and when police officers testify against them and another police officer prosecutes them, they can hardly be blamed for thinking that the dice are loaded against them before the games starts.” Tupper Bigelow, himself a magistrate, wrote these words in 1962, deeply critical of the reputation of Magistrates’ Courts as Police Courts.

(S. Tupper Bigelow, A Manual for Ontario Magistrates (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1962) p. 33.)

By 1934, the legislation began to eliminate the references to “police.” The reality of these courts, however, continued to be intertwined with police functions.[38] The overlap between judicial and police powers remained a challenge to judicial independence.

While The Magistrates Act, 1934 declared that in the future every police magistrate and deputy police magistrate was to be styled as a magistrate or deputy magistrate and the court known as the magistrates’ court, the terminology of police magistrates and police courts persisted. In his 1962 book, A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, S. Tupper Bigelow wrote: “[the] public still refers to Magistrate’s Courts as ‘police courts,’ although in Ontario, that objectionable nomenclature was abolished long ago.”[39]

When hearing breaches of provincial statutes or municipal bylaws, it was a common practice for police officers to conduct the prosecution and examine the witnesses — many of whom would be other police officers. Yet another police office might serve as court clerk — and the entire trial would take place in a police station.[40]

Structural Organization of the Bench

Accommodations: In the early years, a magistrate’s access to courtrooms was rather tenuous. “A police magistrate…shall have the right to use any court room or town hall belonging to a county or municipality in which he may sit or hold his court, but in so using a court room or a town hall he shall not interfere with the ordinary use of the court room for other courts or with the use of the town hall for the purposes for which the same is maintained.”[41]

In practical terms, this meant that the accommodation for a magistrate’s court depended on his relationship to the municipal officials. If those relations were not good, the proceedings could be held in desperately inappropriate and inadequate spaces.[42]

Senior and Chief Magistrates: The structural organization of magistrates’ courts began when The Magistrates Act, 1922 allowed for the appointment of four police magistrates for the City of Toronto and provided that one of those could be designated senior magistrate.

Court Facilities in 1967

“In Watford, the magistrate conducts the court in the basement of the public library. The room is a sort of furnace room. When the furnace comes on during the sessions of court it is necessary either to turn it off or submit to the noise…In Metropolitan Toronto, the accommodation provided for magistrates can only be termed disgraceful. One court is held in a police station…”

(McRuer Report, p. 539)

The senior magistrate was given authority to:

- Designate courts to be held;

- Allocate cases to courts;

- Assign police magistrates to the courts;

- Investigate all complaints as to the conduct of police magistrates;

- Give directions regarding the business of the courts; and

- Arrange for sittings of the court.

In 1934, the legislation was amended to establish magisterial districts across the province, and designate senior magistrates for each district. Every magistrate was given jurisdiction to act anywhere in Ontario, though he might be assigned to a specific district.[43]

In 1964, The Magistrates Amendment Act created the new position of chief magistrate within Ontario and stipulated that the chief magistrate should be the senior magistrate of the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto. This legislation provided that “the chief magistrate shall have general supervisory powers over arranging the sitting of magistrates and assigning magistrates for hearings, as circumstances require.”[44]

Payment of Magistrates, Part-time Magistrates and Extra-Judicial Employment: Independence Issues

“The salary structure is quite illogical.” These were McRuer’s comments about the payment of magistrates in 1968.[45] That salary structure had been illogical since the first magistrates were appointed, resulting in significant variances in remuneration across the province, and questionable practices about how magistrates were appointed and paid for their services.

Perennial issues relating to the adequacy of salaries paid to magistrates prevailed, particularly in light of the compensation judges appointed by the federal government were receiving. Poor pay was a subtext of Magistrate George Denison’s memoir, written in 1920 about his long career which began in 1877: “The question of salary did not weigh with me a particle. I have always felt that the pecuniary side of any question should not be allowed to have undue weight…Solomon says, ‘How much better it is to get wisdom than gold.’”[46] But he also makes it very clear that provincially appointed magistrates were treated differently than federally appointed judges when he recounts the story of an offer made to him to join the High Court of Justice as a judge: “I was pleased at the offer, but declined it at once (although my salary would have been much larger), because I felt my position was more important in many ways, and that I might be much more useful to the community where I was.”[47]

Though fixed by the province, the salaries of magistrates varied throughout Ontario. Typically, salaries were higher in the most populous jurisdictions where courts would be busier. However, much depended on the favour in which the magistrate was held. As Magistrate Bigelow wrote in 1962, “annual increments are usually, though not always, granted.”[48] In other words, each magistrate negotiated his own salary. Further, magistrates who were lawyers were paid more than those who were not.

As McRuer wrote, “If the magistrate is qualified for the office, there should be no distinction between those who are qualified lawyers and those who are not…the salaries provided have no relation to the importance of the office. It is not an office to be filled by older men who may regard it as a form of semi-retirement. Men appointed to it should be vigorous young persons who bring to the office a broad practical experience of life gained from some years in the practice of law. They should be paid salaries that will enable them to live and educate their families in dignity.”[49]

Reading between McRuer’s lines, it is easy to imagine a bench of older men, retired from earlier careers, merely supplementing their incomes with a magistrate’s slim salary. Further, it is easy to imagine situations where those keen to augment their incomes might compromise their independence to please their government paymasters.

Part-time magistrates posed another challenge to the independence of the courts. It was common for a part-time magistrate to continue practising as a lawyer or running a business. The potential for conflicts of interest was often realized. McRuer details one such “undesirable” situation: “Certain members of a labour union were accused of assault. At the trial before a part-time magistrate they received sentences they felt were out of proportion to other sentences imposed in other cases of assault. The magistrate was a part-time magistrate who practised as a lawyer. It was alleged that he acted for clients who were employers who had disputes arising out the employee/employer relations with the union in question. We are quite prepared to assume that the magistrate acted entirely without bias, but the fact that the circumstances were such as could give rise to the appearance of bias is sufficient to give just cause to the complaint.”[50]

Reflections on Magistrates’ Court in 1950s Toronto

The Honourable Roy McMurtry who went on to become the Attorney General of Ontario and Chief Justice of Ontario had his first courtroom experiences in Magistrates’ Courts:

“Soon after I entered law school (in 1954), I became interested in particular in the human dramas that occurred daily in the Magistrates’ Criminal Courts in the east wing of City Hall. Many of the magistrates were not legally trained and, as a result, were often overly influenced by the Crown prosecutors. Although the magistrates generally attempted to discharge their duties in a conscientious fashion, I often gained the impression that, rather than the important legal presumption of innocence, there was an evidentiary onus on the accused to demonstrate innocence. The fundamental requirement that, before the accused could be convicted, the Crown must satisfy the court beyond a reasonable doubt, was not always respected. The advantages that the prosecution generally enjoyed in the Magistrates’ Courts, which heard over 90 percent of the criminal cases, were increased significantly by the fact that many of the accused were not represented by lawyers. Until a “fee for service” legal aid plan began in 1967, the only legal assistance available for the indigent was provided by a few voluntary counsel. The local Sheriff’s Office attempted to assist the unrepresented accused by administering a sporadic criminal pro bono legal aid service.”

(Roy McMurty, Memoirs and Reflections, (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2013) pp. 51-52.)

Appointment and Removal of Magistrates

In 1877, Magistrate Denison was on his way home from Russia when he received a cablegram from the premier of Ontario asking if he would accept an appointment of Police Magistrate of Toronto. “This surprised me,” wrote Denison, “as I had made no request for any appointment, and had no desire to take a public office.”[51]

For many years, the appointment process for magistrates was frankly political and informal. Political parties engaged in the practice of appointing their own supporters. In essence, the provincial government of the day invited people to become magistrates.

While a great many fine magistrates had been appointed, McRuer commented negatively on the “corrupting” influence of the appointment process. “It is not consistent with the elementary concepts of justice that one who has attained office merely by political service should have the right to preside over the liberty of the subject.”[52]

Once the government appointed a magistrate, it continued to maintain control over that appointee by retaining the ability to remove that magistrate. In 1952, a provision was added to The Magistrates Act which allowed the provincial government to remove a magistrate who had been in office for two years for “misbehaviour or for inability to perform his duties properly.”[53] The legislation did not clarify what was meant by “misbehaviour or inability to perform duties,” leaving the ability to remove a magistrate for almost any reason. Despite the fact that this provision had never been used between its introduction and 1968, McRuer roundly criticized it as being an “unwarranted interference with the independence of magistrates.”[54] McRuer called for the introduction of a body that could, while maintaining the independence of the magistrates, allow for the presentation of “grievances with respect to the conduct of members of the judiciary.”[55]

While there was no statutory requirement for magistrates to have legal training, by 1968, of the 114 magistrates in Ontario, 90 were qualified lawyers and there were calls for all magistrates to have legal training. As McRuer wrote: “In view of the importance of the office and the complexity of many cases that come before the magistrates’ courts, it is an unjustified encroachment on the rights of the individual that he should be compelled to have his rights determined by one untrained in the law, or have to submit to the alternative of taking his case to a higher court in order that he may have a decision from a legally trained mind. This is without question an infringement on basic civil rights.”[56]

Expansion of Jurisdiction

An Appointment to Magistrates’ Court: A Call from the Police Chief

Judge Donald Dodds served first as a magistrate, then as a judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and the Ontario Court of Justice in Oshawa. Here is his own account of being appointed as a magistrate.

“I was appointed to the bench on January 15, 1967. The process followed an unusual course from start to finish, and totally unlike the one followed today.

It started when the city police chief, aware of the pending retirement of the presiding magistrate, Frank Ebbs, inquired if this would be an appointment that would be of interest to me. A few days later, Richard Donald, a city lawyer, came to my office and asked if there was any truth to a rumour I was about to be appointed and, if so, would I entertain the possibility of selling him my practice. Nothing came of this rumour but eventually Richard and I did form a law firm under the name Dodds and Donald.

Three years later, however, the matter sprang up once again.

When I appeared in the Magistrates’ Court in Bowmanville, His Worship Ronald Baxter, upon seeing me, invited me into his chambers to congratulate me on my appointment to the Oshawa bench. I assured him that this was not the case.

In the circumstances, I decided to telephone the office of the provincial secretary and inquire if there was any substance to this recurring rumour. A few days later I received an invitation to meet with the Deputy Minister. That was in November 1966.

The rest, as they say, is history.”

(Donald Blake Dodds, A History of the Provincial Court in the Region of Durham (October, 2009) [unpublished])

By the late 1960s, 95 per cent of people charged with indictable offences in Ontario were tried by magistrates. That meant only five per cent were heard by federally appointed judges in “superior courts”. All summary offences made their way to magistrates’ courts and, depending on the type of summary offence, were heard by either magistrates or justices of the peace.[57]

Let’s look at the statistics for 1965: an astonishing 2,089,648 cases were disposed of in the magistrates’ courts across the province.[58] The population for the province had yet to hit 7,000,000 by 1965.

In criminal matters, by 1965, the jurisdiction of the magistrate had evolved to include the power to sentence the accused to life imprisonment and impose corporal punishment.[59] In many criminal cases, an accused person had the choice to be tried by a magistrate, judge alone or judge and jury. The majority of the criminal cases heard by magistrates were those where an accused elected to be tried by a magistrate. This speaks to the importance of the magistrates’ courts – and the expertise they had developed despite years of neglect.

Serious criminal cases often attract attention. They tend to involve the most heinous offences – murder and serious physical assaults, for example, that fill newspapers and the writings of legal scholars. But, for the average person, the trial of summary offences is for most “the only image of the administration of justice.”[60] The magistrates’ courts is where alleged breaches of, for example, the Highway Traffic Act, municipal noise by-laws and minor criminal cases landed members of the public. In 1965, the magistrates’ courts heard 15,509 indictable offences and 2,074, 139 summary offences. This is where the public met the court.[61]

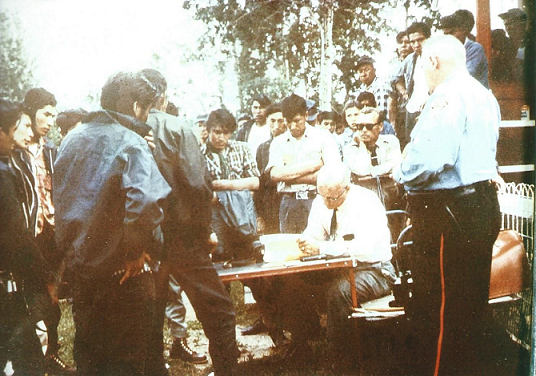

Magistrate Jack Cox presiding in Fort Hope, Ontario. This photo was taken sometime between 1957 and 1963. It was provded by Mary Jane Willis, daughter of Constable George A. Sangster, court officer, standing to the left of Magistrate Cox.The magistrates’ courts could be found in the province’s most remote communities, often in unorthodox settings, like this one. Fort Hope, also known as Eabametoong, is an Ojibway First Nation in Kenora District, Ontario. This photograph was provided courtesy of Mrs. Mary Jane Willis.

Powers of Police Magistrates

“Not long before my appointment (in 1877), the powers of police magistrates had been very much enlarged, and shortly after they were more increased. With the consent of the accused, I have been able to try all the serious offences, except murder, manslaughter, rape, high treason, and one or two crimes connected with the misuse of explosives, without a jury, and with power in some cases to sentence to imprisonment for life. This wide jurisdiction has made my Court, for the last forty years, the principal court of Ontario, for up to two or three years ago about ninety percent of the indictable offence have, with the consent of the accused, been tried by me.”

(Police Magistrate George T. Denison in Recollections of a Police Magistrate, pp. 3-4)

What Cases Were Heard in Magistrates’ Court?

Indictable offences

These are the most serious federally created offences. They include crimes such as murder. Magistrates would hear such cases only where the accused person chose to have a trial before a magistrate (as opposed to a federally appointed judge sitting with or without a jury).

Summary offences

These are less serious or “petty” federal offences such as causing a disturbance in a public place. By law, these cases were heard by magistrates.

Hybrid offences

These are federal offences that the prosecutor could choose to be tried as a summary or indictable offences. Magistrates heard hybrid offences that were tried as summary offences.

Provincial or municipally created offences

Offences created under provincial statutes or regulations, or by municipal bylaws, were heard by magistrates or justices of the peace.

Since 1967, many indictable offences have become categorized as hybrid. This has contributed to the fact that the vast majority of criminal cases are now heard in the Ontario Court of Justice.

Women Join the Bench

The 1921 Magistrates Act recognized a significant change – in a city with a population of 100,000 or more, a woman magistrate or deputy magistrate might be appointed if desirable. If the city had more than one magistrate, such an appointment might be in addition to any magistrate then in office or to fill an existing vacancy. That provision – considered progressive at the time, but now decidedly out of date – remained on the statute books until 1952.[62] The first female magistrate was Margaret Patterson, appointed in 1922 to sit in Toronto’s Women’s Court. A physician by training, she brought a moralistic approach to the bench with her efforts to rescue women from vice and immorality.

Funding of the Magistrates’ Courts

The system for funding magistrates’ courts across the province contributed to its “piecemeal” state.[63] Here’s how it worked. The province paid the salaries of magistrates. The courts themselves were mainly organized, staffed and financed by municipalities and counties.[64] “The service provided by these courts depended on the interest of the community and the amount of money available.”[65]

Before 1859, municipalities were responsible for financing the administration of justice — from supporting a jail and a courthouse, to paying court staff. Only in the northern districts of Ontario was the province responsible for the administration of justice.

In 1859, the province took over the cost of financing the administration of “criminal” justice, which was limited to those matters which were found in the Criminal Code. Everything else continued to be financed by municipalities, including the maintenance of court buildings and the salaries of court officers.[66]

The result? An enormous disparity of what justice looked like across the province. This explains why magistrates’ courts were conducted in furnace rooms in some towns and proper courthouses in others, and why police officers served as court officers in some places, while others had well-trained court clerks.

Assessing Costs Against Convicted Persons, Accounting for Costs

In the late 1800s, “costs” — fees and charges required by law to be paid to courts or their judges or justices of the peace — were routinely assessed against people convicted of offences. “Costs” are different from fines. Fines are levied for punishment. Costs are levied to compensate a municipality or the province for the expense of the prosecution.

Before 1954, when an accused person was convicted of an indictable offence, the court had the power to order the convicted person to pay “the whole or any part of the costs or expenses incurred in and about the prosecution and conviction for the offence of which he is convicted.”[67]

This provision was dropped from the Criminal Code when it was revised in 1954, but the power to award costs with respect to the trial of summary offences remained. For example, fees were payable to justices of the peace for hearing cases, fees were payable for interpreters and, unbelievably, the convicted person could be ordered to pay the cost of conveying himself or herself to prison.[68]

If a convicted person could not afford to pay the costs, the court could order the sale of the person’s possessions or impose a term of imprisonment. The “debtor’s prison” was still a very real possibility for many impoverished people in 1967.[69]And, of course, there was the obvious conflict of court officials — including magistrates and justices of the peace — having a monetary interest in securing the conviction of an accused person.

To make this situation even more objectionable, the practice of awarding costs varied dramatically across the province. This meant that, by 1968, costs were waived by some jurisdictions and, in others, people paid the full freight if they were convicted of a summary offence.[70]

Juvenile and Family Court Judges

Introduction

In 1867, there were no juvenile or family court judges in Ontario. In fact, there were no specialized courts to consider matters affecting children or families at that time.

By 1967, juvenile and family courts were spread — in a hodge-podge fashion — across the province. Over this period, these courts gradually acquired a significant jurisdiction which fell into three categories:

- Conduct of the child – the “juvenile delinquent”;

- Conduct of adults toward the child – “contributing to juvenile delinquency”; and

- Obligations of parents towards one another and their children.[71]

Despite this evolution, these courts were acknowledged as “the poor country cousins to the magistrates’ courts.”[72] Remember — as recently as 1967, the magistrates’ courts were considered to be the most “neglected” courts in Ontario.[73] So, where did this leave the poor relations — the juvenile and family courts and its collection of judges?

Let’s begin by tracing the history of these courts and their judges beginning at the end of the 19th century when social reformers turned their focus on children, pleading for more sympathetic treatment of the youngest members of society — “juveniles” — by the justice system.

The Juvenile in the Court System

In 1867, the trials of children and adults were held in the same criminal courts, and children served their sentences in the same prisons along with hardened adult criminals. The age of criminal responsibility was seven years — and, in 1967, it was still seven.[74]

Social reformers recognized that “juveniles” should be treated as children needing help, encouragement and guidance — not as criminals. Legislators began to respond. In 1893, the first act for the protection of children was passed in Ontario, setting out special treatment for children who had broken the law.[75]

This Children’s Protection Act was limited, however. It only applied to cases where children were convicted of offences under provincial statutes. In such cases, power was given to the court to commit them to the care of Children’s Aid Societies,[76] which were created by this legislation.

The Introduction of the Juvenile Delinquents Act: “Aid, Encouragement, Help and Assistance”

The “Waifs and Strays” of Toronto in 1889

“Six small boys presented themselves at Police Headquarters yesterday asking for three years in the reformatory so they could learn to read and master a trade. They were referred to Inspector Archibald who told them to come back this morning. Half an hour later they returned with a hand sleigh which they claim to have stolen from 90 Yonge Street. All pleaded guilty to theft and were sent down.” (“From Police Blotters,” Toronto World, 14 December 1889.)

“The Police Magistrate yesterday discharged six little boys who had stolen a hand sleigh in order to go to the reformatory.” (“Jottings about Town,” Toronto World, 31 December 1889.)

Because the federal government had (and continues to have) exclusive jurisdiction over the criminal law, children convicted of criminal offences — no matter how minor — were still treated as adults in Ontario after 1893. That only changed in 1908 with the enactment by the federal government of The Juvenile Delinquents Act (the “JDA”).[77]

The social nature of the JDA stated in the act itself: “…every juvenile delinquent shall be treated, not as a criminal, but as a misdirected and misguided child, and one needing aid, encouragement, help and assistance.”[78]

Despite these lofty philosophical intentions, implementation proved to be a challenge. The JDA, wrote Ted Andrews, the former Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division), “turned out not to be the panacea for which social reformers had hoped.”[79]

What happened?

First, the JDA was not applicable across the province, creating a confusing and uneven collection of juvenile courts. By 1952, only 30 municipalities in Ontario had set up juvenile courts.[80] Special juvenile courts were established only in those areas where they were authorized — and paid for — by local authorities. If a child committed a criminal offence on one side a boundary road, she could be charged as an adult. If she committed the same offence on the other side of the road, she could be charged as a juvenile delinquent, if that locality has set up a juvenile court under the JDA.[81] Only in 1963 was the JDA finally proclaimed for all jurisdictions in Ontario.[82]

Second, the judicial officers sitting in the juvenile courts were often not trained for the position of “juvenile judge.” In 1910, with the enactment of The Juvenile Courts Act, the province took a convenient step and simply appointed every magistrate and federally appointed judge to be a “juvenile judge” in all areas where the JDA applied.[83] This meant that no training or special skills were required to take on the new role of juvenile judge. This situation continued for almost sixty years. In 1967, no special qualifications or training were required for a judge hearing juvenile matters,[84] this despite repeated calls for juvenile judges with training in both law and social sciences, capable of comprehending the issues facing young people and families.[85]

The Jurisdiction of Juvenile Court Judges

In 1967, the JDA applied in Ontario to children apparently or actually under the age of 16. A child was a “delinquent” if he or she violated any provision of the Criminal Code, any provincial or federal statute or any municipal by-law. A school-age child who was “habitually absent” from school was also considered a juvenile delinquent. A child guilty of “sexual immorality or any similar form of vice” was also a delinquent.

This broad definition resulted in the situation where the term “juvenile delinquent” applied to a wide range of offences – from murder to unlawfully riding a bike on the sidewalk.

The court could take several courses of action if a child was found to be delinquent, ranging from levying a fine to placing the child in a foster home or under the care of a Children’s Aid Society to sending the child to a training school.

These powers, combined with the broad definition of the term “delinquent,” could result in a child being sent to a training school for the breach of a city by-law – such as unlawfully riding a bike on the sidewalk.

Juvenile court judges also had a wide jurisdiction to try adults for contributing to juvenile delinquency and to impose penalties on parents or guardians of juvenile delinquents. With the first JDA in 1908, social reformers had aimed to eliminate the stigma of treating children as “little criminals” or “convicts.” By the end of this period, however, the term “juvenile delinquent” had acquired that very stigma.

The JDA had significant “rehabilitative” purposes. The act provided for the service of probation officers not only to provide background information about the juvenile delinquent for sentencing purposes but also as correctional counsellors with juveniles placed under their supervision. Recognizing that juveniles should not be jailed with adults, the act also provided for the establishment of detention homes for children.

(Sources: JDA, R.S.C., 1952, c. 160; McRuer Report, pp. 550-554; H.T.G. Andrews, Family Lawyer in the Family Courts, (Toronto: The Carswell Company Limited, 1973) pp. 2-5.)

The Court’s Jurisdiction Expands to Family Matters

In 1934, The Juvenile and Family Courts Act was passed.[86] This legislation broadened the scope of the work of the juvenile courts and added “family” matters to the work of the court. These family matters pertained primarily to issues of child neglect and domestic relations within the family.

The juvenile and family courts were given jurisdiction over a collection of the provincial statutes, including the following:

Tragedy in Port Arthur

“Estranged Husband Slays Judge, Wife and Self at Port Arthur,” read the newspaper headline on June 21, 1949 in the Fort William Daily Journal. It was a tragic chapter in the history of the juvenile and family courts. Judge B.J. McKitrick, together with Irene Gray, was shot and killed in the courtroom by Mrs. Gray’s husband, William Gray, a former police officer. Mr. Gray, who was appearing on charges of not financially supporting his three young children, then turned the gun on himself. Judge McKitrick, a former social worker, was appointed in 1945 to the juvenile and family court in Port Arthur, which is now part of the municipality of Thunder Bay.

- The Child Welfare Act

- The Children’s Maintenance Act

- The Deserted Wives’ and Children’s

Maintenance Act - The Minors’ Protection Act

- The Parents’ Maintenance Act

- The Schools Administration Act, and

- The Training Schools Act.[87]

Passage of the 1934 statute created a period of confusion as the courts had different names and jurisdictions, with some called juvenile court, others known as family court, and yet others called juvenile and family court. Because each municipality financed its own such court with “marginal budgets,” variance — and confusion — was the rule.[88]

As detailed by the Ontario Law Reform Commission, much of the confusion was eliminated in 1954 when an amendment to The Juvenile and Family Courts Act gave all these courts the same jurisdiction. Until the passage of The Provincial Courts Act in 1968, however, there was no central organization or financing of Ontario’s juvenile and family courts.[89]

Further, while the 1934 statute provided for the appointment of juvenile and family court judges, these judges were all deemed to be ex officio magistrates for the province with the jurisdiction to try criminal cases. Practically speaking, this meant that many juvenile and family judges were also doing the work of a magistrate.[90] By 1967, for most of these judges, juvenile court cases only accounted for approximately one-third of their work.[91]

An Inequitable Kind of Justice?

Family Court Matters

After enactment of The Juvenile and Family Courts Act in 1934, what sorts of matters could be added to the workload of the judge sitting in these courts?

Here are three examples:

The Minors’ Protection Act: This legislation act was passed for the purpose of protecting young people from an “unsavoury” environment existing in pool halls — “which were the favourite hangouts for criminals, gamblers and unrefined and immoral men. The keeper of such premises was not allowed to admit any person under 18 unless he was accompanied by his parent or a legal guardian.”

The Deserted Wives’ and Children’s Maintenance Act: This act was intended to force husbands and fathers to provide financial support for their wives and children who had been deserted by them without providing them with adequate financial support when able to do so. After a financial “maintenance” order was made, the judge could also make provision as to custody and access of children.

The Training Schools Act: This act provided that any person could bring any child under 16 years of age before the Court, and the Court could send that child to a training school for an indeterminate period if the child’s parent or guardian, in the view of the Court, was “unable to control him or to provide for his social, emotional or educational needs.” The Court also had the power to commit to a training school any child between 12 and 16 who had contravened any statute which contravention would be punishable by imprisonment if committted by an adult. Once committed to a training school, the child became a ward of that school until he or she turned 18, unless the wardship was terminated earlier.

(H.T.G. Andrews, Family Law in the Family Courts (Toronto: The Carswell Company Limited, 1973) pp.7-9.)

By the 1960s, the marginalized approach to the juvenile and family courts was roundly criticized. As McRuer wrote,

“The change of attitude that is required when one moves from an ordinary court to a juvenile and family court is difficult. In the latter court, the adversary system is of lesser importance. One is more concerned with the social welfare of the people appearing before the court and in seeking solutions to their difficulties within the social context, than is the case with other courts. A magistrate functioning within the framework of an adversary system under strict and formal rules requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt, and where punishment must be a consideration, is engaged in an inquiry of an entirely different one in which he seeks solutions where these attributes are not the predominant features. It is not right to vest these different aspects of the administration of justice in the same judicial officer….The juvenile and family court can no longer be considered to be merely an ‘extra’ court or an added function of the county court judge or the magistrate.” [92]

“An inequitable kind of justice.” This was Andrews’ simple and concise view of the justice meted out to juveniles and families. However, Andrews recognized the contributions of the judicial officials who sat in these courts – particularly in the early days. In the face of all the challenges presented, the judges “kept the Juvenile Courts from going off the rails.”[93]

Appointment and Qualifications of Juvenile and Family Court Judges

Serving “At Pleasure”

“It will not be taken amiss, I am sure, if I point out that up until 1941, magistrates, who of course are appointed by the Provincial Government of the day, held office only during the pleasure of the Lieutenant Governor in Council, i.e., the provincial cabinet. In 1941 the Magistrates Act was amended to provide that salaried magistrates, after being in office for two years, could only be removed upon the recommendation of a Commissioner after a public inquiry, such Commissioner being required to be himself a Judge of the Supreme Court of Ontario. Even this amendment left many magistrates without such protection and subject to being dismissed at the will of the Provincial Government. That has been the law of this Province by statute then since 1941, the only real changes in the intervening years being brought about by the Provincial Courts Act, 1968.”

(Justice Donald A. Keith, Inquiry Re Provincial Judge Lucien Coe Kurata, 1969, p. 7.)

“Convenience appears to have dictated the appointment of magistrates and county court judges to occupy the juvenile and family court bench,” wrote McRuer in 1968.[94] That aptly summed up the situation. By 1967, the majority of juvenile and family judges were magistrates whose main work was sitting in the magistrates’ courts. This situation often made it “unfeasible” for the magistrate to “give adequate time to his juvenile and family court work.”[95]

There were no legal qualifications to become a judge of a juvenile or family court. Judges held their positions “during good behaviour,” meaning there was no “security of tenure.” “Once a man is appointed, the tenure is only dependent upon good behaviour,” wrote McRuer.[96]

Salaries for judges were paid by municipalities — and tended to be lower than what magistrates of the day were making. As Andrews pointed out: “Salaries were not high enough to attract many lawyers. There was more dedication than remuneration. After all, this was an experiment in sociological justice.”[97] This meant that those who were appointed to magistrates’ courts and juvenile and family courts (“two hatters”), received two salaries, one from the province and one from the municipality.[98] The salary received for work as a juvenile and family judge tended to be the lesser of the two, however.

The result was a court that was often considered to be an “extra.” For many of the judges, the work was simply an added function to their regular judicial positions. Further, no training was given to these judges despite the “change in attitude that was required when one moves from an ordinary court to a juvenile and family court.”[99]

Administration and Funding of the Juvenile and Family Courts

Funding – specifically, the lack of it – was a constant challenge for the juvenile and family courts.

Unlike the magistrates’ courts which, by the late 1960s, were financed by the provincial government, the juvenile and family courts were typically financed by municipalities within counties across Ontario. In parts of northern Ontario, the province did finance juvenile and family courts — but the vast majority were funded by municipalities.

By 1967, problems, caused by lack of funding, were “acute” in most juvenile and family courts, according to McRuer.[100] Andrews was far blunter: “There was a great disparity in facilities and staff of the various courts throughout the province. Unlike the Magistrates’ Courts, the Juvenile and Family Court was not a revenue producing one. In fact, it was almost a total liability.”[101] What does Andrews’ mean by this? The “revenue” he wrote about refers to the fines levied on and collected from offenders in magistrates’ courts for infractions such as speeding and parking offences. Juvenile and family courts were typically not levying fines and, therefore, not generating revenue.

Andrews went on to give a good sense of the ad hoc approach taken to these courts: “It usually turned out that the courts that fared the best were the ones where the Judges had the best relationships with the municipal and/or county councils, some of which were not fully convinced of the Court’s usefulness. Besides having a working knowledge of the law, sociology and administration, Judges were expected to be good public relations men, as well, if they hoped to have an efficient Court.”[102]

Procedure and Structure of Juvenile and Family Courts: Social Physicians

As Andrews wrote, family courts were considered to be experiments in sociological justice – and this caused a degree of nervousness within the court system. How to protect the civil rights of people coming before these courts, yet still achieve the social objectives they were designed to accomplish?

“The function of the judge is not so much to determine guilt as to find out the underlying causes which have brought the child before the court, and when these have been determined to prescribe treatment,” wrote McRuer. “He is a social physician charged with diagnosing the case and issuing the prescription. This cannot be properly performed if he is surrounded by too many legalistic trappings; nevertheless, there must be some basic ones.” [103]

McRuer went on to reinforce the need to balance the social function of the court with the need to, as he put it, “dispense justice according to the law” like every other court.[104] He recommended the development of general rules of procedure to be followed by all juvenile and family court judges — and that recommendation came with a pointed criticism: “The rule of thumb of the individual judge is not sufficient.”[105]

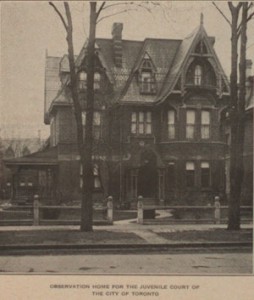

A Glimpse at Toronto’s 311 Jarvis Court

“311 Jarvis” — that address has had a long and storied history in the realm of juvenile and family courts in Ontario. The story begins in 1922 with the decision of the City of Toronto’s Juvenile Court Special Committee to purchase the house at 311 Jarvis for a sum “not to exceed $25,000” to serve as the Observation Home for Toronto’s Juvenile Court. Until 1954, 311 Jarvis served that purpose. Typically, the home had a daily population of 10 to 12 children and the average length of stay was two to three days.

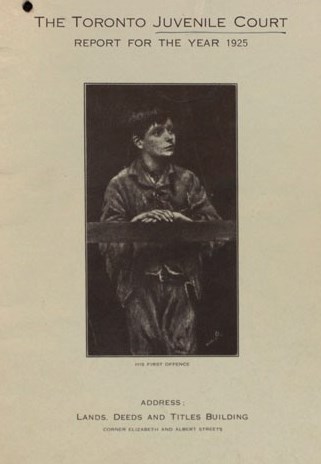

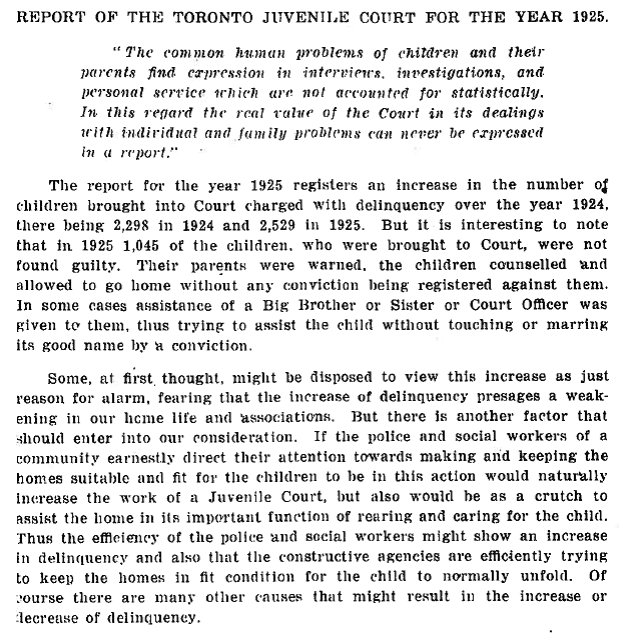

The Report of the Toronto Juvenile Court for the Year 1925 provides a strong indication of the sentiments of the day regarding “delinquent” children. That report is introduced with a quote from author Victor Hugo: “All the vagabondage in the world begins in neglected childhood.” It was seen as a civic duty to repair such neglect.

(The Toronto Juvenile Court Report of the Year 1925. City of Toronto Archives, CTA, Fond 2, Series 60, Item 1706)

In the 1950s, Judge V. Lorne Stewart of the Juvenile and Family Court campaigned to have a facility which housed all services under one roof: the court, family counselling, probation services and detention services. This was a radical idea for the time, a facility that was more clinic than court. As Stewart wrote: “The perennial discussion as to whether the Juvenile and Family Court is more clinic and welfare agency than it is a court points up the significantly important double role that these courts are called upon to perform…Its purpose is mending the rifts in family life; establishing a just and reasonable financial plan of support when the home has fallen apart; and providing proper control and guidance for children who break the law or are in need of care and protection…How far (the court) should move out into the treatment area is a moot question but the court that is able to write its own prescription can usually command results more quickly and frequently achieve more satisfactory results.” (“The Juvenile and Family Court,” in S. Tupper Bigelow, A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1962) pg. 81.)

In March 1957, the new 311 Jarvis opened its doors to extensive coverage of the building and Judge Stewart in the newspapers of the day. “The approach to delinquency at the Jarvis St. Centre will be as progressive as the building’s unusual front — a towering wall of cut limestone broken by hundreds of small windows. Children received by the centre and judged to be delinquent will undergo a solid week of observations stressing psychiatric examination and a review of their homes and conditions there…’Don’t get the idea we will be pampering the youngsters here,’ observed Senior Judge V. Lorne Stewart in The Toronto Daily Star, on March 12, 1957, as he proudly showed off the new building. ‘We believe in handling discipline by being humane.’” In 1966, the province assumed responsibility for all detention homes, including 311 Jarvis.

Interior of Juvenile Court, 311 Jarvis Street, 1956 (Photo: Barry Stewart, City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 35, File 50)

In the late 1990s, when Stewart was 88, he returned to visit 311 Jarvis and was saddened to see his creation eroded. He was accompanied on that visit by Judge James P. Felstiner, who also served as a juvenile and family court judge. Judge Felstiner wrote of that visit: “After seeing the children in handcuffs in court and the dirty, crowded, windowless steel cells in which the detained children are now held, tears started to come to his eyes and he asked me to take him home. Only after his death did I discover what he had written about that day: ‘What did I see – handcuffs, locked doors, more court than clinic.’ His dream was no more.” (James P. Felstiner, “Lives Lived,” The Globe and Mail (June 17, 2002))

Conclusion

The proliferation of courts that characterized the 1867-1967 period changed in 1968 with the creation of provincial courts with two divisions – criminal and family. A new era had begun in the evolution of what would become the Ontario Court of Justice.

| An Act Respecting Qualifications of Justices of the Peace Subsequently re-enacted as: The Justices of the Peace Act | Legislation Governing Justices of the Peace This legislation, originally enacted before Confederation, was revised, amended and re-enacted numerous times and later consolidated in 1952. The 1952 statute, while periodically amended and revised, formed the basis of the justice of the peace system until the mid-1980s. |

|---|---|

| The Justices of the Peace Act, 1897 | Right to Use Town Hall A justice of the peace was given the right to use town hall of a municipality, but not so as to interfere with its ordinary use, unless another suitable place was provided by the municipality. This provision existed until the 1950s. |

| The Justice of the Peace Act, 1935 | Minimum Property Requirements All references to minimum property qualifications were repealed. Prior to this date, justices of the peace were to be of “the most sufficient persons dwelling in the places” for which they were appointed and were to have land valued at $1200 or more. |

| Criminal Code, 1892 | Separate Trials for Children Section 550 of the Criminal Code required children to be tried separately from adults. Trials of children were to be held “in camera,” without the public present. |

|---|---|

| The Children’s Protection Act, 1893 | Children’s Aid Societies Neglected and delinquent children could be assigned to the care of Children’s Aid Societies. Delinquency related only to convictions under provincial statutes. |

| The Juvenile Delinquents Act, 1908 | Establishment of Juvenile Courts Local authorities could establish Juvenile Courts to handle young offenders and adults who contributed to their delinquency. |

| An Act Respecting Juvenile Courts, 1910 | Police Magistrates as Juvenile Courts Police magistrates were constituted as juvenile courts. A justice of the peace, on the written request of the Attorney General, could act as a juvenile court judge in a specific case. |

| The Magistrates Jurisdiction Act, 1929 | Jurisdiction Conferred to be Juvenile Court This Act enabled additional jurisdiction to be conferred on Magistrates’ Courts to become Juvenile Courts. |

| The Juvenile and Family Courts Act, 1934 | Family Courts Juvenile Courts could also become Family Courts. |

| The Magistrates Act, 1934 | Juvenile Court Judges to be Magistrates Judges and deputy judges of Juvenile Courts became ex officio magistrates, but could only act as such when directed to do so by the Attorney General. |

| The Juvenile and Family Courts Act, 1954 | Consistent Name: Juvenile and Family Court Juvenile Courts and Family Courts were all renamed Juvenile and Family Courts. |

| The Juvenile Delinquents Act, 1963 | Full Proclamation of Juvenile Delinquents Act The Juvenile Delinquents Act was proclaimed for all counties, provisional districts and separate cities and towns in Ontario. |

| The Juvenile and Family Courts Act, 1964 | Senior Judge A senior judge and an associate senior judge could be designated whenever there was more than one judge of a Juvenile and Family Court. |

| The Juvenile and Family Courts, 1967 | Chief Judge of the Juvenile and Family Courts The Lieutenant Governor in Council could appoint a chief judge of the Juvenile and Family Courts with “general supervisory powers over arranging the sitting of judges and family court and assigning judges for hearings, as circumstances permit.” |

| The Provincial Courts Act, 1968 | The Provincial Court (Family Division) The Juvenile and Family Courts were subsumed into the Family Division of the new Provincial Court. |

| The Municipal Corporations Act, 1849 | Police Office Magistrates This pre-Confederation statute established police offices in towns listed in an attached schedule. The police magistrate for each town was required to dispose of business brought before him as a justice of the peace. |

|---|---|

| An Act Respecting Police Magistrates, 1877 | Magistrates in Ontario Towns and Cities The Lieutenant Governor in Council was directed to appoint a police magistrate in each city and town where the population exceeded 5000 and, under certain conditions, in smaller towns and in counties. |

| The Magistrates Act, 1922 | Designating a Senior Magistrate The Lieutenant Governor in Council could appoint four police magistrates for the City of Toronto, one of whom could be designated senior magistrate. |

| The Magistrates Act, 1926 | Female Magistrates Female magistrates could be appointed, but only in cities with populations of 100,000 or more and only where a resolution of council declared that it was desirable for a woman to be appointed. |

| The Magistrates Act, 1934 | Change of Name: Magistrates Court The Police Magistrates Court became known as the Magistrates’ Court. Each magistrate had jurisdiction across Ontario but could be assigned to a specified magisterial district. |

| The Magistrates Act, 1941 | Removal from Office A magistrate who held office for more than two years could only be removed for cause, such as misconduct or inability to continue. |

| The Magistrates Act, 1952 | Repeal of Special Provisions for Female Magistrates The special provisions regarding female magistrates were repealed. |

| The Magistrates Amendment Act, 1964 | Chief Magistrate The position of Chief Magistrate for Ontario was created, with “general supervisory powers over arranging the sitting of magistrates and assigning magistrates for hearings, as circumstances require.” |

| The Provincial Courts Act, 1968 | The Provincial Court (Criminal Division) The Magistrates’ Courts were subsumed by the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) of the new Provincial Courts. |

- Zuber, T.G. Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1987), p. 28 ↩

- Civil matters are those concerned with the private affairs of citizens, for example marriage, property ownership, contractual disputes rather than criminal matters ↩

- Zuber Report, p. 25 ↩

- McRuer, J.C. Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights, Volume 2 (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1968), Volume 2, p. 527. ↩

- Bigelow, S. Tupper. A Manual for Ontario Magistrates, (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1962), p78. ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol 2, p. 526 ↩

- Peter Russell, The Judiciary in Canada – The Third Branch of Government (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, 1987), pp. 208-210 ↩

- Mewett, Alan W. Report to the Attorney General of Ontario and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario. (Toronto: Ministry of the Attorney General, 1981) p. 2 ↩

- Mewett Report, p. 3 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 515 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 520 ↩

- Zuber Report, p.22 ↩

- An “information” is a sworn statement which charges that a particular individual has committed a criminal act. A member of the public or a police officer can come to a justice of the peace and swear an information before that justice of the peace. This commences a criminal prosecution ↩

- Summary offences are less serious criminal offences which usually carry a penalty of a fine or a short jail term ↩

- Mewett Report, pp. 2-3 ↩

- Mewett Report, pp. 2-3 ↩

- Mewett Report, pp. 2-3 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 516 ↩

- An Act for the Qualification of Justices of the Peace, Statutes of Upper Canada 1842, 5 Victoria, c. 3, ss. 1, 3 ↩

- An Act Respecting Qualifications of Justices of the Peace, C.S.C., c. 100 (later consolidated by 1952, c. 47) ↩

- Mewett Report, p. 4 ↩

- The Toronto Daily Star, Friday, August 17, 1934 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 517 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 519 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 519 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 520 ↩

- McRuer Report, p. 521 – In 1968, only 89 of the more than 900 justices of the peace were paid on a salary basis. The remainder were paid by fees ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 521 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 523 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 524 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 524 ↩

- Banks, Margaret A., “The Evolution of The Ontario Courts”, 1788-1981″ in Flaherty, David H., ed. Essays in the History of Canada, Volume II (Toronto: The Osgoode Society 1983 492 at p. 546) and McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 526 ↩

- 12 Vict. (1849), c. 81, s. 69 (P. of Can.), Banks, The Evolution p. 546 ↩

- Banks, The Evolution, p. 546 ↩

- Banks, The Evolution, p. 546, RSO 1877, c. 72, ss 1-2; RSO 1887, c. 72, ss. 2, 3, 8, 21 ↩

- Denison, George T. Recollections of a Police Magistrate (Toronto: The Mission Book Company Limited, 1920), p.3 ↩

- Denison, Recollections, p. 3 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 531, Banks, The Evolution, p. 546 ↩

- Bigelow, A Manual for Ontario Magistrates (Toronto: Queen’s Printer, 1962), p. 33. ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 532 ↩

- Magistrates Act, 1926, s. 36(1) ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 538 ↩

- Banks, The Evolution, p. 547 ↩

- Interview of B. Lennox for OCJ History Project, 2014 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 528 ↩

- Denison, Recollections, p. 5 ↩

- Denison, Recollections, p. 4 ↩

- Bigelow, A Manual, p. 4 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 529 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 530 ↩

- Denison, Recollections, p. 1 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 539 ↩

- S. 3, Magistrates Act, R.S.O. 1960, c. 226 – this provision first enacted in 1952 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 541 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 541 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 528 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 526 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 526 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 526 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 527 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 527 ↩

- S.O. 1921 (chap. 41., s. 4), Banks, The Evolution, p. 546 ↩

- Zuber Report, p. 27 ↩

- Zuber Report, p. 26 ↩

- Zuber Report, p. 26 ↩

- Zuber Report, p. 26 ↩

- Crim. Code 1927, s. 1044 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 535 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 536 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 549 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 536 ↩

- Andrews, H.T.G. Family Law in The Family Courts (Toronto: The Carswell Company Limited, 1973, p. 11 p. 11 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 526 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 1 ↩

- An Act for the Prevention of Cruelty to, and Better Protection of, Children, Ont. 1893, c. 45 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 547 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 547 ↩

- The Juvenlile Delinquents Act, R.S.C. 1952, c. 160. , s. 38 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 2 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 548 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 547 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 548 ↩

- Juvenile Courts Act, RSO, 1910, Andrews, Family Law, p. 3 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 558 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, pp. 558-562 ↩

- Juvenile and Family Courts Act, 1934 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 7 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 564 ↩

- Ontario Law Reform Commission, Report on Family Law, Part V, Family Courts, Ministry of the Attorney General, ch. II. ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 8 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 554 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, pp. 560-561 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 6 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 560 ↩

- E.H. Silk, Assistant Deputy Attorney General, Legislature of Ontario Debates, 1961-62, c. 67, s. 4 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 558 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 6 ↩

- Interview of T. Andrews for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 561 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 563 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 10 ↩

- Andrews, Family Law, p. 11 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 555 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, p. 556 ↩

- McRuer Report, Vol. 2, P. 555 ↩