Introduction: Possibilities and Limits of the Judicial Role.

Magistrates: 1920s to 1968

Provincial Court Era: 1968-1990

Ontario Court of Justice: 1990 and Onwards

New Approaches in a New Millenium

Policy Reform

Conclusion

Introduction: Possibilities and Limits of the Judicial Role

Most people would agree that a judge’s main role is to hear cases and render decisions. There is less consensus about the extent to which judges should be active outside the courtroom. What kinds of activities can judges and justices of the peace undertake without compromising judicial independence? Specifically, what can they do to promote law reform, engage with the community, build public understanding of the justice system, and participate in efforts to improve access to justice?

Not surprisingly, the kinds of decisions individual judges and justices of the peace have made about their outside activities differed at various points during the history of the Ontario Court of Justice. In some respects – such as the degree to which judges interact with the community to make the courts more effective – the pendulum has gone back and forth. A fundamental backdrop has been the evolving discussion and debate about the meaning of judicial independence and the application of ethical principles.

This essay considers the possibilities and limits of the judicial role outside the courtroom.

Magistrates: 1920s to 1968

Outside Employment is the Norm

In 1920, Police Magistrate David Hastings was vocal in his opposition to the Ontario Temperance Act and the Attorney General who wanted him to vigorously enforce it. The report of a public inquiry into his conduct reveals a circumstance that would never be possible for a provincial judge in modern times: while on the bench, Hastings also served as the editor of a local newspaper.[1]

Hastings’ outside activities were not unusual. At the time, it was common for magistrates to take on additional types of work. A 1921 Royal Commission report on Ontario magistrates found that, “[i]n many places the Police Magistrates devote their whole time to Magistrates’ work, but as a general rule they are men engaged in active business callings or in professional life…. In thirty-six cities and towns the Police Magistrates are lawyers engaged in active practice.”[2] The report provides specific examples of magistrates who had ruled on cases involving their clients or business associates.[3]

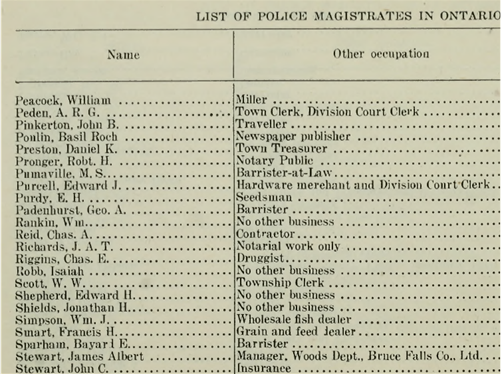

The Royal Commission report provides a fascinating list of other occupations held by Ontario’s police magistrates as of January 1, 1921. In addition to barristers, there was a manufacturer of cement products; a harness maker; a manager of a canning company; builders and contractors; a carriage painter; a restaurant owner; a grocer; real estate and insurance agents; postmasters; a miller; farmers; a seedsman; dealers in grain, feed, lumber, coal and wholesale fish; a ticket agent; a storekeeper and merchants; court and town clerks; newspaper publishers; notaries public; an associate coroner; a druggist; a dentist; and a physician.[4]

The report recommends that the work of police magistrates be performed by specially qualified men “devoting their whole time to it and engaging in no other business.”[5] While this recommendation was made in 1921, a prohibition on outside employment for provincially appointed judges did not actually occur until 1968. The report also recommended that magistrates should not serve as members of police commissions,[6] a change not instituted until 1984. The approach adopted by this Royal Commission was clearly well ahead of its time.

We would not tolerate for a moment the practice of law or the carrying on of any other business by our Judges: in fact they are prohibited from so doing by Statute.

The objection in the case of Judges applies with at least equal force to Police Magistrates.[7]

One reason for the persistence of ‘other occupations’ was the fact that magistrates’ salaries were “sadly inadequate.”[8] At the time, a fee system was still in place which remunerated magistrates when they convicted someone, but usually not if they dismissed the case.[9] Although fees were eventually abolished, the adequacy of remuneration for provincially appointed judges remained a sore point for many years.

Although the problem of outside work by Ontario’s magistrates was identified in 1921, it lingered as an issue for more than 40 years. It was still an issue when James McRuer released his report from the Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights in Ontario, in 1968.

It is improper for one holding a judicial office of this character to be engaged at the same time in the practice of law or any business… There should be no room for suspicion that the magistrate presiding at a trial may be influenced by his relations with his clients or his business connections. It is most undesirable that lawyers should be appearing before the magistrate one day and carrying on ordinary legal business with him the next day.[10]

McRuer was also critical of the common practice of Ontario magistrates to serve as police commissioners. He reported that 37 magistrates were employed by 68 boards of commissioners of police, “for which they are in some instances paid substantial salaries.” His recommendation in this regard was unequivocal. “Magistrates ought not to be members of Boards of Commissioners of Police for many reasons. Not the least of these is that there ought not to be an employer-employee relationship between judicial officers and the members of the police force.”[11]

The issue of outside employment was even more pronounced for justices of the peace who, for many decades, had served on a part-time, fee-for-service basis. In the 1960s, being a justice of the peace was still often seen as a side line to another type of work, whether as a court clerk or in other functions. The risks of this approach were highlighted in Professor Alan Mewett’s comprehensive report on justices of the peace in 1981.[12]

Provincial Court Era: 1968-1990

Outside Employment is the Exception

A judge must be… removed from any sophisticated entanglements, be they political, personal or financial, which might seem to influence him in the exercise of his judicial functions, let alone entanglements that might actually influence him.

Shimon Shetreet, Judges on Trial[13]

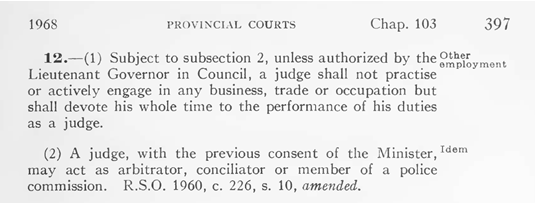

Upon proclamation of the Provincial Courts Act in December 1968, the Magistrates’ Courts, justices of the peace, and Juvenile and Family Courts were transformed into the Criminal and Family Divisions of the new Provincial Courts. The statute included a clear statement to convey the expectation that judges’ ‘whole time’ should be devoted to their court duties. While acting as an arbitrator, conciliator or member of a police commission was not prohibited, consent of the Minister would now be required to assume these roles.

Notwithstanding the express permission to act as a member of a police commission, that practice eventually came to an end with the passage of the Courts of Justice Act, 1984. This statute, which replaced the Provincial Courts Act, did not include the possibility of obtaining consent to act as an arbitrator, conciliator or member of a police commission.[14]

The Family Court Judge as a “Community Motivator”

An issue judges often face is the absence of resources to deal with the legal or broader social problems facing those who appear before them. Many judges, as respected members of the community, have taken the opportunity to influence how the community and government respond to such challenges. No better example exists of judges acting to address the reality of inadequate resources than the work done by members of the Provincial Court (Family Division) bench in the 1970s.

It’s all about what happens after you make your decision.

Jim Felstiner, former Family Court judge[15]

The goal was simple. Faced with a virtual absence of needed community resources, many Family Court judges decided to encourage the creation of new facilities and programs to help make youth and family justice more effective. Some might say these judges crossed a line: that their activities affected their actual or perceived impartiality. Others would assert they left a lasting legacy that continues to benefit Ontario children and families years later.

A motivating factor was the judges’ frustration that training schools funded by the Ministry of Correctional Services were often the only place they could send young offenders. Community-based care, offering support and treatment generally closer to home, was usually considered to be a much more effective alternative. Such care was, however, simply not available in many communities. Moreover, there was often no place available to keep youth in the community while they were before the Court, or to provide an expert assessment of them and their families. Building community resources became a way to ensure more effective outcomes, especially when dealing with youth under the Juvenile Delinquents Act and assisting families in child welfare cases.

The types of resources developed included:

- group homes,

- child-friendly local observation and detention facilities,

- treatment programs,

- Family Court clinics

- diversion programs,[16]

- mediation and conciliation programs, and

- shelters for abused women

The judges who took on this role were numerous, including: Maurice Genest in London, Joe James in Toronto, Jim Karswick and Warren Durham in Brampton, David Steinberg and John Van Duzer in Hamilton and George Thomson in Kingston. They came to realize that as influential voices in their communities they could motivate positive change. They used their voices with the strong encouragement and blessing of Chief Judge Ted Andrews.

So my role basically, I felt, was to encourage and support the judges and try to instil in them a need to be a motivator within the community. You see, in Family Court a judge can only be as good as the resources available to him…. If you have only got a training school to send kids to, then that is where they go. But if you have a group home which you can place them in, on probation, and make it a condition of probation, this is an added resource, and that is great…. We had to be proactive and get things done, mobilize the community, make them aware of the needs.[17]

Community organizations and volunteers also became leaders in the creation of juvenile and family resources. Governments, too, had a role to play. Child psychiatrist John S. Leverette acknowledged the role of the Ontario government and the judiciary when he wrote that “…court-related clinic services in the province of Ontario, Canada were robustly developed with cooperation between the ministries of the Attorney General, Health, Community and Social Services, and Corrections. Key to the inter-ministerial coordination and high profile for these services was leadership from the Office of the Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division).”[18]

The federal government played an important role by providing funding to test diversion programs and conciliation services as it gave consideration to replacing the Juvenile Delinquents Act and introducing a new Divorce Act.

Concerns began to arise that some judges were becoming too close to, or dependent on, particular programs. The criticism focused in particular on Judge Warren Durham, sitting in Brampton, with regard to the number of children he had placed with one group home operator, Viking Houses. At the time, Family Court judges could invoke a powerful tool in section 20(2) of the Juvenile Delinquents Act. This provision enabled the judge to order an amount of money the municipality had to contribute to a child’s care once the judge had determined the child’s placement.

The municipalities of Toronto and Peel were concerned about the impact such orders were having on their budgets. Legal challenges were launched including two cases involving Viking Houses which ultimately were heard by the Supreme Court of Canada. The result: the power to order municipal payments was declared to be unconstitutional.

“Half of the group home residents

sent there by one Peel Region Judge”

One July 31, 1975, a Globe and Mail

article reported that half the children

in the Viking 1 group homes “came

from one juvenile court-that

presided over by Judge Warren

Durham in Peel Region.”

The article added that,

“The judge’s enthusiasm for Viking, and his

aversion to training schools, has

caused a controversy in the region, in

part because the judge can act

independently of the local Children’s

Aid Society, which is not a Viking fan,

and order a delinquent child placed with Viking,

the bills to be picked up

by the municipality.”

The municipalities of Toronto and Peel were concerned about the impact such orders were having on their budgets. Legal challenges were launched including two cases involving Viking Houses which ultimately were heard by the Supreme Court of Canada. The result: the power to order municipal payments was declared to be unconstitutional.

Although some Family Court judges remained active in the development of community resources after the 1970s, that role became less common. According to Jim Karswick, “Judicial outreach was beginning to meet resistance in the 1980s. At meetings of the association of family judges there were many who did not think that this was the role of the judge. They thought we should stay in the courtroom and do our work as judges, not go out and interact with the community.”

Nonetheless, the legacy of the “community motivators” in the Family Court has remained in the form of community resources created in the 1970s and 1980s that are still in place many years later.

Brampton

In Brampton, Karswick recalled that “[t]he Family Court clinic, supervised access centre, mediation service, and community service orders all came about because of judges making contact with organizations, institutions and people in the community. It was common among Family Court judges to do outreach work. Without it, the resources we needed would not have been there.”[19]

London

In London, the Centre for Children and Families in the Justice System has acknowledged the “proud legacy” of Maurice Genest, also a former Family Court judge, in relation to a Family Court Clinic.

In the early 1970s, Judge Genest mustered a small group of local professionals to pursue the idea of a local Family Court Clinic, one modelled after that in Toronto. The major stumbling block – funding – fell away when Dr. Naomi Rae-Grant secured support from the Ministry of Health. As Judge Genest continues the story: “a modest complement of staff was hired, a volunteer board of directors was established, and in 1974 the London Family Court Clinic was started.”

What was then two people conducting “pre-disposition assessments” for the juvenile court is today a multi-faceted agency with 22 staff, six vibrant clinical programs, productive linkages to community partners, a high-quality applied research program, in-demand training services, and the capacity to generate an impressive array of resources to aid intervention and prevention. In 1974, we saw 40 youths. This year [2004], we saw almost 800.[20]

Kingston: One Community’s Response

George Thomson, a Family Court judge in Kingston in the 1970s, recalls one community’s efforts to meet the needs of at-risk children and troubled families:

I remember well my excitement in 1972 as I drove up Brock Street in Kingston to see, for the first time, the Family Court to which I had just been appointed. I equally remember my shock when I discovered it was located in a decrepit red brick house and hearings were held around a table in the dining room, while those waiting sat in the small living room.

Even that paled in comparison to the realization of how little was available in the community to support the work of the Court. Almost daily I was reminded of the limits of my ability to respond to children and families in crisis, juvenile delinquency, family violence, and marriage breakdown because the needed resources and programs simply weren’t there. If the possibilities I saw when offered the position were to become other than false hopes, I needed to play a role in changing this bleak situation.

Four years later, Chief Judge Andrews publicly commended the Kingston community for the way it had come together to create the needed resources. The Court now had access to a Family Court clinic to assess children and their families, an observation and detention home, a juvenile diversion program, a volunteer probation service, a youth crisis centre and several new community-based group homes for youth. Kingston had opened up one of the early shelters for abused women and was testing a court-based conciliation service that was settling most of our support and custody cases. And a new Family Court had just opened that offered night court and child care for those who needed it.

I believe there were three things that brought about this transformation and made my job as a Family Court judge so much easier and more effective.

The first is that Kingston was and is a unique community for its size. It has a large teaching hospital, one of Canada’s leading universities, and a host of other institutional settings that attract persons with the skills and experience to develop new programs and lead significant change.

Second, and the essential element in all communities that see and respond to the needs of others, was the participation of many committed individuals who gave their time and expertise to develop these programs. The examples were many and varied. They included social workers,[21] child psychiatrists,[22] educators,[23] and many enthusiastic and committed law students.[24]

Third, and just as important, was the realization that I, as the Family Court judge, needed to play an active role to help ensure that essential supports to the Court were in place. This is a decision that my Chief Judge, Ted Andrews, actively encouraged.[25]

Sometimes my role involved identifying the need. At other times, it was to find the individuals who could turn a general idea into a concrete program. I sought government funding to test new approaches and then make them sustainable. And I encouraged research so we could learn from our successes and failures.

The biggest gamble I made was to help set up an observation and detention facility, a place where kids who had to be held could stay in the community instead of over 100 miles away in Ottawa. I found Mike Ozerkevich who was teaching child care workers at the local community college. We got a bit of money from the Ministry of the Attorney General. And we got a local businessman to provide a broken down stone building in mid-town Kingston. When the centre opened, it was almost all staffed by the community college students. In retrospect, that was a risky thing to do: a detention home run by students. The current facility grew from that. It was a great resource to try things out.

In my mind, there was no reason to fear that these community activities would compromise my independence within the courtroom. Many Family Court judges across the province responded willingly to Chief Judge Andrews’ expectation that they take on a leadership role within their communities. This was a distinguishing feature of the Provincial Court (Family Division) in the 1970s.

As I reflect back 40 years later, I recognize that this form of “judicial activism” raised legitimate questions about how far a judge can go to engage the community. However, I am proud that in Kingston and many other Ontario communities, judges made the effort to develop resources so that children and families could have better outcomes.

A Public Voice Defining the Limits

Chief Justice Bora Laskin and Two Provincial Court Judges

Beginning in the late 1970s, the issue of what a judge may do or say outside the courtroom became the subject of debate – led by the Canadian Judicial Council[26] and its Chair, Chief Justice Bora Laskin.

In 1977, George Thomson took on a full-time assignment with the Ontario government as an Associate Deputy Minister to head a new children’s services division. Although he was no longer sitting in court, he retained his status as a Provincial Court judge and returned to the bench five years later. “My Chief Judge and the Attorney General had given their permission and so I thought there was no problem. However when I showed up at judicial education program a year later in Ottawa, I found that Chief Justice Laskin had spoken the night before and had called my public service appointment (without using my name) ‘a blot on judicial independence which should not be tolerated’.”[27]

Thomson was not the only one to encounter Chief Justice Laskin’s disapproval. In May of 1983, Laskin addressed the Convocation of Lakehead University. He explained how his association with universities had to terminate once he became a judge. This was because “universities had become enveloped in litigation which beset them from time to time.” Laskin said that he would not be a member of the university’s Board of Governors or Senate. “Were I to be involved in University policy, I would, according to my code of judicial behaviour, have been precluded from taking the post….[A judge’s] choice of a vocation has meant, in my view, a deliberate choice to leave public affairs alone…”[28]

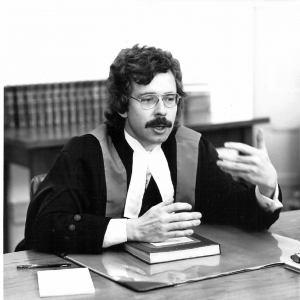

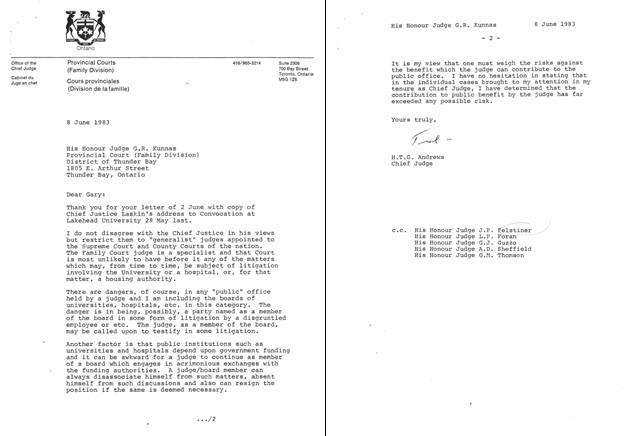

This was an uncomfortable moment for Provincial Court judge Gary Kunnas who was on the podium with Laskin. He was a judge in Thunder Bay and a member of the board of Lakehead University.

Kunnas wrote a letter seeking advice from Ted Andrews, Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division). Andrews replied that the Family Court, as a court of “specialist judges”, is “most unlikely to have before it any of the matters which may, from time to time, be subject of litigation involving the University or a hospital, or, for that matter, a housing authority.” Andrews’ bottom line was that, in his experience, “the contribution to public benefit by the judge has far exceeded any possible risk.”[29]

Government Consults with Judges on New Laws

During the Provincial Court era, Family Court judges struck a law reform committee and were actively involved in discussions about how to reform child welfare laws. Heather Katarynych, who became a provincial judge subsequent to working for the Ontario government in the Children’s Services Division in the late 1970s, reflects on that period.

“I recall how Family Court judges from the Provincial Court reached out in the late 1970s to inform policy development and legislative reform, especially in the area of child welfare law. Day in and day out, these judges saw how the existing laws played out for the children, families and state agencies appearing in their courtrooms. They brought a perspective that no one else could bring to the reform agenda: a focus on real life mischiefs in existing law that had been crying out for a cure for a very long time.”[30]

Another example of judges being well heard in law reform was the extensive consultation process that led to passage of the federal Young Offenders Act in 1982. One reason judges were well consulted was that the government brought in a Saskatchewan Provincial Court judge, Omer Archambault to lead the exercise. Not only were Ontario judges included in the public discussions but they also had direct access to Archambault.

The family judges used their access to Archambault to request a provision to strengthen judicial control in the area of sentencing. They were concerned that after a judge’s order had placed a child in a secure setting, correctional authorities could unilaterally decide to relocate that child before the term of the order had expired. Archambault agreed to add a provision to the new legislation so that the judge’s approval would be required before taking a child out of a closed custodial facility.[31]

Judges’ Views Hit the Media

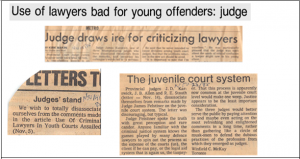

Occasionally the different perspectives of judges on matters affecting the Court spilled into the public realm. On November 5, 1985, a headline in the Ottawa Citizen read: “Use of lawyers bad for young offenders: judge.” The article reported on remarks made by Judge James Felstiner at a conference of the Probation Officers Association of Ontario. Felstiner was reported to have said that the widespread use of criminal lawyers in the juvenile justice system was harmful to the children.

“When you add a lawyer, you add a lot of problems to a case,” said Felstiner, asking how a 13-year-old makes sense of a defence lawyer who tells the child he will plead not guilty even though the child has admitted committing the crime. The judge wondered how a lawyer can explain this in light of a moral system against telling lies developed by parents, teachers and clergymen…. If Ottawa wanted to criminalize the system for young kids 12 and over, they sure got it.[32]

In response to a similar article in The Globe and Mail headlined “Use of Criminal Lawyers in Youth Courts Assailed,” three Family Court judges (J.D. Karswick, J.B. Allen and R.E. Stauth) submitted a letter to the editor expressing the wish to “totally disassociate ourselves” from Judge Felstiner’s comments.[33] This created the unusual situation of provincial judges expressing contrary views in the media about a public policy issue.[34] Other interested parties – including lawyers, social workers and youth services advocates – joined in the debate, publicly supporting or denouncing what Judge Felstiner had said.[35]

The Criminal Lawyers’ Association launched a complaint against Judge Felstiner, “questioning the judge’s ability to deal fairly with young offenders who are represented by lawyers.” The Ontario Judicial Council dismissed the complaint.

On all the evidence we are not persuaded that the remarks made by Judge Felstiner, as reported in the media, were such as to lead to the perception by the public generally and by the defence bar and young offenders specifically, that a young person appearing before him with counsel might be the subject of resentment and unfair treatment.[36]

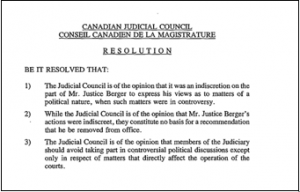

A Cautionary Tale: The Case of Thomas Berger

In the 1980s, the case of Thomas Berger became a highly visible example of limitations being placed on a judge’s ability to speak publicly on issues. Berger, a judge of the British Columbia Superior Court, had chaired three Royal Commissions in the 1970s, including one on the proposed MacKenzie Valley Pipeline. A 1981 article in the Ottawa Citizen reported him saying that “the decision of all Canadian first ministers to abandon native rights as one of the prices for agreement on the constitution was ‘mean-spirited and unbelievable’.” A week later, Berger authored a piece in The Globe and Mail that elaborated on this and other political views.[37] Berger’s public comments generated a complaint to the Canadian Judicial Council.

Following an investigation, the Canadian Judicial Council resolved, in 1983, that Berger’s actions were “an indiscretion” but constituted no basis for a recommendation that he be removed from office.[38] Shortly afterwards, Berger left the bench.

Following an investigation, the Canadian Judicial Council resolved, in 1983, that Berger’s actions were “an indiscretion” but constituted no basis for a recommendation that he be removed from office.[38] Shortly afterwards, Berger left the bench.

The Berger case focused attention on what judges could do or say outside the courtroom without compromising their independence. Professor Jacob S. Ziegel wrote that, “Chief

Justice Laskin was… emphatic in his opposition to judges becoming involved in political debates off the bench. He told his lawyerly audience in the aftermath of the Berger affair that ‘[a] judge has no freedom of speech to address political issues which have nothing to do with his judicial duties’.”[39]

Not everyone was as cautious as Laskin. John Sopinka, another justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, later asked, “Must a judge be a monk?” He asserted, “No longer can we expect the public to respect decisions from a process that is shrouded in mystery and made by people who have withdrawn from society.”[40]

Attorney General Ian Scott: A Restrictive View

Rosalie Abella is an example of a Provincial Court judge who had a strong voice in public policy issues in the 1970s and 80s. She took time off from sitting in court to conduct a study on access to legal services by persons with disabilities , to lead a ground breaking Royal Commission on equality in employment, and to chair the Ontario Labour Relations Board. Chief Judge Ted Andrews supported her in all of these activities.[41]

When Ian Scott became Ontario’s Attorney General in 1985, he took a restrictive view of the roles judges could assume. He told Clare Lewis that he could not remain a Provincial Court judge while serving as Police Complaints Commissioner and he took the same position regarding Judge Rosalie Abella and the Ontario Labour Relations Board. Abella chose to stay with the Board even though losing her judge’s pension despite 12 years on the bench.[42]

Ontario Court of Justice: 1990 and Onwards

Serving on Commissions, Task Forces and Committees

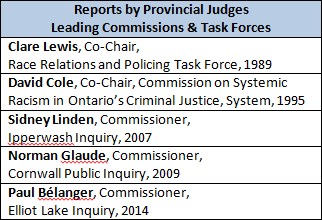

As the calibre of appointments was heightened and the credibility of the Court improved, provincial judges began to receive government appointments to sit on commissions of inquiry and task forces. In 1989, the Ontario government appointed Judge Clare Lewis to serve as chair of the Race Relations and Policing Task Force. A few years later, with permission from Chief Justice Linden, Justice David Cole was freed from full-time judging in order to co-chair a commission on systemic racism in the criminal justice system. Since then, several other judges from the Ontario Court of Justice have been appointed to chair inquiries into important public policy issues.

Although recognized as a suitable role, even here the appointment of sitting judges has not been free of discussion and debate. The Canadian Judicial Council “Protocol on the Appointment of Judges to Commissions of Inquiry” concluded while valuable, such appointments also present risk.

Public inquiries chaired by judges play a very valuable role in Canada. They do, however, present risks to the judiciary. The objective of these guidelines is to ensure that the judiciary can continue to serve the public interest in this important way when asked to do so, while at the same time maintaining public respect and confidence for the judicial office and the independence of the judiciary.

Case Study: Justice Lesley Baldwin

A Judicial Council matter involving Justice Lesley Baldwin illustrates the challenge for a judge who takes on an important social and justice policy issue outside the courtroom.

In autumn 1998, at the request of the Attorney General, Baldwin began a leave of absence to chair the Joint Committee on Domestic Violence. The Committee’s mandate was to provide advice on implementing recommendations from an inquest held to examine recent and notorious domestic murders. Baldwin possessed extensive expertise in this area stemming from her work prior to being appointed to the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) in May 1997.

“Chief Judge Linden advised me to be careful not to become involved in political activism but supported me in taking on this role. Throughout my term on the Committee, including when the Committee report was released, I made the decision not to be available to the media.”[43]

After submitting the Committee’s final report in August 1999, Baldwin returned to the Ontario Court of Justice to sit as a full-time judge. Almost a year later, following a spate of fatalities arising from domestic violence incidents, members of the Committee became concerned about the delay in adopting recommendations they felt might have prevented those deaths. Baldwin agreed to write to the Attorney General in her capacity as the former Committee chair. In a brief letter, she noted “I… can add parenthetically that I have observed no noticeable changes in the manner in which counsel are approaching these difficult cases in the criminal courts in which I preside. ”

A complaint was subsequently filed with the Ontario Judicial Council by a group of defence counsel, signed by Alan Gold, president of the Toronto-based Criminal Lawyers’ Association.

The alleged misconduct was described as follows.

Specifically, the misconduct is described by Presenting Council Mr. Hunt to be the continuing contact with Executive Branch over matters of government policy affecting the area of criminal justice administration beyond the time frame during which permission had been granted for Justice Baldwin to assist the Executive Branch-thereby aligning herself with initiatives or strategies that were being presented by a particular group. Such conduct raised questions with respect to her ability to remain impartial and independent on issues that might come before her.[44]

“I was very alone dealing with this,” said Baldwin. “The Chief’s office took a hands-off approach because the Chief Judge chaired the Judicial Council. There was little or no support from other judges. Nothing was said by the Ontario Conference of Judges, which at that time didn’t see this as part of its role. It was a very difficult time. On the other hand, the media was generally very supportive, and I received two warm letters of support from [former Supreme Court of Canada Justice] Claire L’Heureux-Dubé”.[45]

After a public hearing with many media representatives present, the Judicial Council found that “the writing of the letter was more in the nature of a reaffirmation by Justice Baldwin of the views earlier expressed in the Committee’s report.” The Council concluded that there had been no misconduct, dismissed the complaint, and recommended that Baldwin be compensated for her legal costs. The decision was delivered 19 months after the complaint had been submitted.

“I look back on the work of the Committee with pride. The discussion my case generated gave the issue more profile and probably helped in ensuring our proposals for implementation of the inquest recommendations were acted on. So I now see the benefits of what I did, even though it was a very painful time. As well, the Ontario Conference of Judges now has a media committee and is developing a protocol on when and how it should speak out on behalf of judges dealing with situations like the one I faced.”

Lesley Baldwin[46]

Judicial Conduct and Ethics

Judicial misconduct is something that can result in a judge or justice of the peace being sanctioned or, in the most serious cases, removed from the bench. The Courts of Justice Act provides a mechanism for investigating complaints into judicial conduct. However it does not define the term “judicial misconduct.”

Judicial ethics is the application of values associated with the judicial role to behaviour within and beyond the realm of the courtroom. In some cases, what was once seen as a question of ethics (e.g., sexist behaviour) can later be viewed as misconduct.

Since 1997, three key documents have been produced to provide guidance on ethical issues.

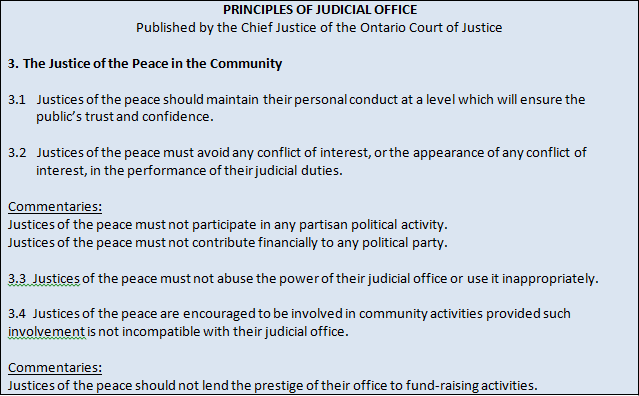

Principles of Judicial Office for Judges

The principles are intended to assist judges in addressing ethical and professional dilemmas. They address the role of the judge in the courtroom, with the Court, and in the community. They were created under the leadership of Chief Judge Linden[47] in consultation with the judges’ associations and adopted by the Ontario Judicial Council in 1997.

Ethical Principles for Judges

In 1998, the Canadian Judicial Council (which investigates complaints of alleged misconduct involving federally appointed judges) published Ethical Principles for Judges to provide guidance on how comportment by judges in and out of the courtroom should reflect such fundamental principles as judicial independence, integrity, impartiality and equality. The Ontario Judicial Council approved and adopted the principles in 2005 upon the recommendation of the Ontario Conference of Judges and the Chief Justice’s Executive Committee. As such, they form part of the ethical standards for judges of the Ontario Court of Justice.

Principles of Judicial Office for Justices of the Peace

The principles are identical to those for the judges, except for the substitution of the term “justice of the peace” for “judge.” This approach respects and recognizes the important role of justices of the peace as judicial officers. The principles were approved by the Justices of the Peace Review Council in 2007.[48]

With the benefit of the three sets of principles, education programs for judges and justices of the peace of the Ontario Court of Justice have been expanded to focus on judicial conduct and ethics and how these concepts are evolving. Education for newly appointed judges and justices of the peace, for example, assist them in the important skills of recognizing ethical dilemmas, thinking through the issues they raise, and identifying possible responses.

The question of what judicial officers may do or say in the community continues to be the subject of debate and discussion. Guidance and education are, however, now available to assist in preventing problems and addressing those that may arise.

New Approaches in a New Millennium

In recent years provincial judges have forged new pathways to engage with their communities and to have a voice in justice reform outside the courtroom. The debate continues with regard to when such activity raises judicial independence concerns or compromises judicial ethics.

Problem-solving Courts

When Family Court judges of the Provincial Court were actively developing community resources in the 1970s and 1980s, the Criminal and Youth Court judges were engaging with the community but in different ways, for example through the introduction of community service orders and other alternatives to incarceration. Beginning in the late 1990s, criminal judges found a new avenue for community engagement through the development of “problem-solving courts in some locations.”[49]

Problem-solving courts focus on issues such as drug offences, mental health, domestic violence, and Aboriginal persons in conflict with the law. The first two problem-solving courts in Canada – a mental health court and a drug-treatment court – opened in Toronto in 1998.

In developing and designing a problem-solving court, judges build close connections with treatment organizations and community leaders who are an essential part of the process.

Justice Judith Beaman was involved in the development of two drug treatment courts in Kingston and Ottawa. She observed that “[t]he work that judges have to do to get funding, secure government approval, and build a partnership with the appropriate treatment professionals is similar to what Family Court judges had to do in the ’70s.”[50]

This is an example of where the sense of what is permissible in terms of interaction with the community has moved in both directions across the spectrum of choices – broadening and narrowing at different points in time.

The problem-solving courts resulted from the pioneering work of certain individuals. Without Justice Paul Bentley and Justice Ted Ormston, there would be no drug treatment or mental health courts. These judges are recognized internationally for their work and they have addressed courts around the world to speak of their experience. Similarly, the first Aboriginal “Gladue” court in Canada (and for a long time the only such court) was a direct result of the work of Justice Pat Shepherd, Justice Brent Knazan and Justice Rebecca Shamai. Former Associate Chief Justice Peter Griffiths

Judges Taking on Related Roles

Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice continue to serve on government-appointed commissions, committees and task forces. Some have begun to take on other roles that might not have met Ian Scott’s restrictive view in the 1980s about what was acceptable, but later came to be seen as compatible with the judicial function. The following serve as just a few examples of initiatives taken in recent years.

Justices Schneider and Ormston – Tribunal Chairs

Justice Richard Schneider, appointed to the Ontario Court of Justice in 2000, also serves as Chair of the Ontario Review Board. This is an independent tribunal that oversees individuals found to be unfit to stand trial or not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder.

From 2014 to 2015, he also served as Acting Chair of Ontario’s Consent and Capacity Board. Most applications to this board involve a review of a person’s involuntary status in a psychiatric facility or a review of a finding about an individual’s incapacity to consent to or refuse treatment. In this role, Schneider succeeded Justice Ted Ormston.

Like Ormston, Schneider sat as a judge in the Mental Health Court in Toronto’s Old City Hall prior to these board appointments. “I was told by Chief Justice Bonkaloto think of it as a secondment – my judicial assignment was to serve as chair of these two boards. The work of the boards – both involving mental health issues – was a natural segue from my work as a judge.”[51]

Chief Justices Linden and Lennox – Commissioner and Educator

Two former Chief Justices of the Ontario Court of Justice – Sidney Linden and Brian Lennox – took on full-time positions outside the Court. Linden was appointed by the Ontario government to become Ontario’s Conflict of Interest Commissioner; Lennox took a position as Executive Director of the National Judicial Institute. Although no longer sitting as judges after moving to these positions, both retained their judicial status.

Justice Wake – Tribunal Vice-Chair

Justice David Wake had served as Associate Chief Justice and as the Local Administrative Judge in Ottawa. In 2013, he received a federal government appointment to serve as Vice-Chair in the Appeal Division of the new Social Security Tribunal. Concurrently, he continues to serve as a judge on a non-presiding per diem basis.

Justice Ebbs – Chair, Shaken Baby Death Review

Public confidence was rocked by the findings of the Goudge Inquiry into Pediatric Forensic Pathology.[52] It was clear that wrongful convictions had occurred due to a reliance on now questionable medical opinions about “shaken baby syndrome” and related issues. In December 2008, following the release of the Inquiry report, Attorney General Chris Bentley announced the formation of a committee of legal and medical experts to review cases in which criminal convictions had resulted from determinations of pediatric head injury.

The Committee was chaired by Justice Donald Ebbs of the Ontario Court of Justice.[53] Justice Ebbs is a former Associate Chief Justice who had also served as Regional Senior Justice of the West Region. At the time of his selection for the Committee, he was a per diem judge, sitting on a part-time basis.

The review was designed “to identify cases where the pathology evidence relied on at trial would be considered questionable in light of current scientific knowledge” and to “advise the Attorney General of concerns relating to the soundness of criminal convictions… in light of today’s understanding of the evolving science.”[54]

The composition of the Committee, with its members drawn from both disciplines [legal and medical], represented an example of a criminal justice system willing to examine itself in order to take action against potential wrongful convictions.[55]

The Committee reviewed and analysed selected cases, including many where medical evidence about had trauma “had been fundamental to the conviction.” Selected cases were subject to additional medical evaluation by a group of international experts. In its report of March 4, 2011, the Committee advised the Attorney General of concerns in four cases.

Policy Reform

For many years, bench and bar committees have brought the judiciary, the bar and other justice personnel together to discuss and resolve problems within a local court.

Recent experience in Ontario with the “Justice on Target” initiative to address criminal court delay has demonstrated that judicial leadership at the central and local levels is an essential component of the reform effort. Although it is always the government’s prerogative to change legislation, there is a growing recognition that effective justice reform requires the involvement of all the players in the system, including the judiciary. The question arises, nevertheless: how to include the judicial voice without compromising judicial independence and impartiality.

Justice on Target

Reflections by Justice Peter Griffiths of the Ontario Court of Justice

“Justice on Target” was a provincial government initiative to reduce the time to trial and the number of court appearances in criminal cases. Our Court was not consulted by the Ministry of the Attorney General about its creation or structure. A Crown Attorney and a Superior Court judge were selected as co-leaders. I was asked by Chief Justice Bonkalo and the Minister to be the lead participant from our Court.

There was widespread concern among the judges about our involvement and our lack of a leadership role. I was not concerned. I saw this as an opportunity to work with others in the justice sector to make the courts more efficient.

As long as the cornerstones of judicial independence were respected, I felt there was nothing to lose and much to gain in working with others to improve the system. The bottom line for me was that we cannot direct judges in the management of individual cases and we cannot compromise our independent role in the scheduling of cases.

I found Justice on Target to be an exciting endeavour that represented several firsts in justice sector collaboration:

- Defence counsel, court administrators, the judiciary, Crowns, police, corrections, and outside experts were all engaged in the process.

- All regions and offices were involved, recognizing that effective solutions must take into account the local context.

- The model for collaboration was designed to be permanent, which helped to build and sustain a commitment to continuous improvement at all levels.

We should not measure the success of Justice on Target solely by how well it met arbitrary numerical targets. The real success was the willingness of all parties to come together to work on solutions. It was important for our judges to be at the table, not as “partners” surrendering judicial independence to the government, but as “good stewards” of a system that operates for the benefit of the people of Ontario.[56]

Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice have also sought other means to inform public policy issues while maintaining the independence of the judicial role. As one of many examples, Justice Rick Libman prepared a research paper in 2010 for the Law Commission of Ontario on “Sentencing Purposes and Principles for Provincial Offences.”[57]

Building Public Understanding

Historically, numerous provincial judges have authored books and articles addressing various legal topics, often aimed at professional and academic audiences.

More recently, there have been attempts to reach out to wider audiences. A notable example is Justice Harvey Brownstone, author of a best-selling book for the general public: Tug of War: A Judge’s Verdict on Separation, Custody Battles, and the Bitter Realities of Family Court. Brownstone is also the first judge of the Ontario Court of Justice to host a television show. Its purpose is to educate the public on family law matters. Such public engagement has been lauded by some and criticized by others – indicative that the debate about what a judge may do and say outside the courtroom is far from over.

A more broad-based technique to help foster public knowledge about the law and legal process has been pioneered by the Ontario Judicial Education Network. “OJEN” was founded by Ontario’s three chief justices, including Brian Lennox of the Ontario Court of Justice. Judge Ted Ormston was very involved in the early days of OJEN.

I would be right up there with the people they classify as an activist judge. I mean, I speak out on many occasions, I think judges should. I was delighted to be asked by Roy McMurtry to be our Court’s representative on OJEN, the Ontario Justice Education Network.[58]

Many justices of the peace and judges directly engage with students and others through OJEN’s educational programs and dialogues.

It’s been very rewarding to assist young people experiencing financial hardship and who want to have a career in the law. In the bursary program, they come to Old City Hall and meet with justices of the peace and sit in court. They get a unique look at the workings of the justice system. We keep in touch and I have been a mentor to many….To be honest, the most valuable part of the schools program is the tour of the cells at Old City Hall – the students are pretty shocked by the conditions. One young man told me, “If I’m in a bad situation where I have to make a choice, there is no doubt which way I’m going — I do not want to end up in those cells.”

Justice of the Peace Lynette Stethem[59]

Judges and justices of the peace also teach at universities and community colleges, speak at conferences, and help to educate the media on justice issues.

In 2001, Chief Justice Lennox actively encouraged judges and justices of the peace to get out and speak to members of the public. To support this judicial role, the following structures and guides were created:

- the Chief Justice’s Advisory Committee on Communications,

- a template to assist judges and justices of the peace in the development of public remarks,

- a speakers program to connect judges and justices of the peace to multicultural organizations, the media, and media students,

- a media guide for the Court, and

- a press officer in the Office of the Chief Justice to provide support and guidance when speaking in public.

The combined effect of these initiatives was to send the clear signal that judicial officers had an approved and supported role to speak to the public about judicial roles and functions.[60]

Conclusion

From the early days of the Provincial Court to the modern era of the Ontario Court of Justice, a common goal has been to find the right balance between helping to make the court system effective, while maintaining the unique, independent role of the judiciary. The discussion has become more nuanced over time and increased support has become available for judges and justices of the peace as they strive to achieve that balance.

While a consensus about the possibilities and limits of judicial activities outside the courtroom can be elusive, there is agreement on the importance of the issue and the need for each judge and justice of the peace to address its implications for his or her role on the Ontario Court of Justice.

- Re Hastings Investigation, Report of the Commissioner Mr. John A. Paterson, K.C., April 29, 1921. Note: There was a period of time in the 1980s during which the Provincial Court had a Civil Division to adjudicate small claims. This represented a move toward having full-time judges preside in small claims court cases – although these continued to be frequently heard by part-time “deputy judges”, many of whom were also involved in the private practice of law or other occupations. In 1990 the small claims function was transferred to the Superior Court where virtually all such cases are heard by deputy judges. Similarly, many administrative tribunals use part-time adjudicators to preside over hearings and make decisions.↩

- Gregory, W. D. et al., Interim Report Respecting Police Magistrates of the Commission to Inquire Into, Consider and Report upon the Best Mode of Selecting, Appointing and Remunerating Sheriffs, etc., etc., Printed by order of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Toronto: Clarkson W. James, printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1921, (1921 Magistrates Report), p. 5.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, p. 8.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, pp. 16-21.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, p. 13.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, p.14↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, p.8.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, p.5.↩

- 1921 Magistrates Report, p.7.↩

- James McRuer, Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights in Ontario, 1968, Vol. 2, p. 529-530.↩

- McRuer, Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights in Ontario, 1968, Vol. 2, p. 542↩

- Mewett, Alan W. Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on the Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario, 1981, pp. 17-18.↩

- See Courts of Justice Act, 1984, s. 53.↩

- James McRuer, Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights in Ontario, 1968, Vol. 2, p. 529-530.↩

- Interview of J. Felstiner for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Diversion programs were aimed at diverting certain cases out of the courts to help children accused of minor transgressions avoid the stigma of being labelled as juvenile delinquents.↩

- Transcript of T. Andrews’ oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1995 (used with permission).↩

- Leverette, John S. “Enhancing the learning curve in child an adolescent forensic psychiatry: inter-professional relationships, resource and policy development.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 2004. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins.)↩

- Interviews of J. Karswick for OCJ History Project, 2012 and 2014↩

- Centre for Children and Families in the Justice System, Year in Review – Tricennial Edition 1974 – 2004, at p. 4.↩

- Molly Knowles, a long-term social worker from a local psychiatric hospital, gave up her job and then, over the next 20 years, led one of the first and best conciliation services for families with support, custody and access disputes before the court.↩

- Child psychiatrists Bob Riggs and John Leverette worked with the Family Court and children’s mental health services to create a Family Court Clinic.↩

- A community college teacher – Mike Ozerkevich– set up an open facility for difficult youth, staffed almost totally by his child care students. Dorothy Neuchterlein, the wife of a visiting professor, established a volunteer probation program.↩

- Two law students – Dick and Sherrie Barnhorst – postponed their legal careers to spend a year establishing a diversion program that remains a vital community resource almost 40 years later. Another law student – Anne Hewitt – left her law course and opened a shelter for abused women. Law students also did research work to promote innovative services for youth. One of them was Donna Hackett who later became a provincial court judge↩

- In an article by Ian Hamilton in the Kingston Whig-Standard, 1976, Chief Judge Andrews is quoted: “From programs developed here (Kingston) will come the impetus to develop similar programs in other parts of the province of Ontario.”↩

- The Canadian Judicial Council has authority over the work of federally appointed judges by setting policies and investigating complaints. However, its policies are often instructive to provincially appointed judges and in some cases have been formally adopted by the Ontario Judicial Council and the Ontario Court of Justice.↩

- Chief Justice Bora Laskin, “Some Observations on Judicial Independence,” Provincial Judge Journal, Volume 4, No. 4, December, 1980, at p.20; Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- Chief Justice Bora Laskin, Convocation Address to Lakehead University, May 28, 1983, pp.1-3.↩

- Letter from Chief Judge H.T.G. Andrews to Judge G.R. Kunnas, Provincial Court (Family Division), June 8, 1983.↩

- Interview of H. Katarynych for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- CP article, “Use of lawyers bad for young offenders: judge,” Ottawa Citizen, Nov. 5, 1985.↩

- “Judges’ stand”, letter from Provincial Judges J.D. Karswick, J.B. Allen, and R.E. Stauth. The Globe and Mail, November 14, 1985.↩

- Interview of J. Karswick for OCJ History Project, 2014.↩

- See for example: Makin, Kirk “Judge draws ire for criticizing lawyers”, The Globe and Mail Nov. 15, 1985.↩

- “Judge receives ‘slap on wrist’ for comments” The Globe and Mail, Feb. 15, 1986. ↩

- The two articles are reprinted as appendices to the Record of the Committee of Investigation into the Conduct of the Hon. Mr Justice Berger and Resolution of the Canadian Judicial Council, 1983. Appendix C: Hill, Bert “Berger blasts ‘mean-spirited’ ministers” Ottawa Citizen, Nov 10, 1981. Appendix E: Berger, Thomas “Steps that’ll give Canada a fairer form of constitution” The Globe and Mail, Nov. 18, 1981.↩

- Report and Record of the Committee of Investigation into the Conduct of the Hon. Mr Justice Berger and Resolution of the Canadian Judicial Council, 1983.↩

- Jacob S. Ziegel, “Judicial Free Speech and Judicial Accountability: Striking the Right Balance”, 45 U.N.B.L.J., 175, 1996, at p.177.↩

- Sopinka, John “Must a Judge be a Monk – Revisited”(1996) U.N.B.L.J. 167, at p. 169.↩

- Interview of R. Abella for OCJ History Project, 2015; Biography of R. Abella on Supreme Court of Canada website.↩

- Interview of R. Abella for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of L. Baldwin for OCJ History Project, 2015↩

- Ontario Judicial Council report, In the matter of a complaint respecting the Honourable Madam Justice Lesley M. Baldwin, 2002 (“Baldwin report”).↩

- Interview of L. Baldwin for OCJ History Project, 2015. Letters dated Sept. 17, 2001 and July 5, 2002 to L. Baldwin from C. L’Heureux-Dubé.↩

- Interview of L. Baldwin for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- The Courts of Justice Act 1994 authorized the Chief Judge to establish “standards of conduct for provincial judges.”↩

- Under section 13 of the Justices of the Peace Act, the Associate Chief Justice-Coordinator of Justices of the Peace obtained jurisdiction to establish standards of conduct for all justices of the peace in Ontario. This includes the authority to create a plan for bringing those standards into effect once they have been reviewed and approved by the Justices of the Peace Review Council.↩

- In 1998, the first two “problem-solving” courts in Canada opened in Toronto: a mental health court, established in May of that year, and a drug treatment court, established in December. These courts represented a departure in the handling of criminal charges for certain segments of the population.↩

- Interview of J. Beaman for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of R. Schneider for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- The Honourable Stephen T. Goudge, Report on The Inquiry Into Pediatric Forensic Pathology in Ontario, 2008.↩

- The other members of the committee were: Dr. Michael Pollanen, Chief Forensic Pathologist for the Province of Ontario; Dr. Dirk Huyer, Regional Supervising Coroner for the Regions of Peel, Halton and Counties of Simcoe and Wellington; Marie Henein, Senior Criminal Defence Counsel and President of the Advocates’ Society; and Mary Nethery, Director of Justice Excellence and Senior Crown Attorney.↩

- Ebbs, D. et al. Committee Report to the Attorney General: Shaken Baby Death Review, March 4, 2011 (Ebbs Committee)↩

- Ebbs Committee, p. 2.↩

- Submitted by P. Griffiths to the OCJ History project, 2015.↩

- Libman, Rick “Sentencing Purposes and Principles for Provincial Offences” (research paper prepared for the Law Commission of Ontario, Summer 2010).↩

- Transcript of T. Ormston’s oral history interview, Osgoode Society, 1995 (used with permission).↩

- Interview of L. Stethem for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of P. Griffiths for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩