Dr. Margaret Patterson and the Toronto Women’s Court

Colonel George Taylor Denison

Three Chief Magistrates

Judge S. Tupper Bigelow: A Man of Many Interests

Dr. Margaret Patterson and the Toronto Women’s Court

In 1911, prompted by concerns about the treatment of women in Toronto’s police courts, members of the Toronto Local Council of Women (TLCW) began attending daily court sessions to observe and record proceedings involving women defendants.[1] What they observed was deeply troubling. The issue was not with the judiciary or court staff but rather with members of the audience. As Council member Margaret Patterson later recalled, “the younger women, who were compelled to appear in the police court, were subjected to a great deal of unpleasantness, not by the officials of the court but by the men who collected in the court as spectators. These men took down their names and addresses and followed them afterward for immoral purposes.”[2] In cases where women were sentenced to incarceration, Council members observed that men took note of the length of their sentences, and women reported “being met when they came out of jail by these men, who, taking advantage of their lonely, often friendless, and penniless condition, induced them to go into immorality.”

Armed with the data they had collected, the TLCW applied to the Board of Police Commissioners for the creation of a separate women’s court, “to which men would not be admitted unless they could show just cause for being there.”[3] Despite some initial resistance, the Board formally approved their request on February 5, 1913, and the Toronto Women’s Police Court heard its first cases on February 10, 1913.

The creation of the Toronto Women’s Police Court, one of the earliest women’s courts in North America and the first of its kind in Canada, was part of a broader movement for “woman-specific legal justice.”[4] Men continued to have a significant presence in the Women’s Court, however, both as defendants charged with “morals offences” and as clerks, witnesses, police officers, and lawyers. In fact, for the first eight years of its operation, the Women’s Court was presided over by Colonel George Taylor Denison, a well-known, highly experienced, and male police magistrate. It was not until Denison’s retirement in 1921 – and again at the urging of the Toronto Local Council of Women – that a female magistrate was finally appointed to preside over the Women’s Court.

That magistrate was Margaret Patterson. Appointed on January 4, 1922, Patterson was the first woman magistrate in Ontario and only the fourth in Canada. “When, in 1920, Denison announced his imminent retirement, the TLCW ‘and kindred organizations’ were quick to act, sending a deputation to the newly elected United Farmers of Ontario (UFO) and ‘asking for legislation providing for and, in due course, the appointment of a woman magistrate in Toronto.’ In 1921 the UFO, attentive to the demands of its recently enfranchised female supporters, amended the Police Magistrates’ Act to enable any Ontario city with a population over one hundred thousand to appoint a female magistrate.[5]

Patterson was a woman both of, and ahead of, her time. Prior to her appointment, Patterson studied medicine at the University of Toronto’s Women’s Medical Centre and then received her Master of Surgery degree from Northwestern University in Chicago. Following an internship at the Detroit Women’s Hospital, she travelled to India as a medical missionary in 1900. From 1900 to 1907 she served as the director of the Seward Memorial Hospital in Allahabad, and in 1902 received the Kaisar-i-Hind medal – awarded for “distinguished service in the advancement of the interest of the British Raj” – recognition of her work to combat an outbreak of bubonic plague. Patterson’s mission in India also foreshadowed her later efforts to rescue women from vice and immorality as a magistrate of the Women’s Court. Between 1903 and 1905, she served as the medical adviser to Lord Kitchener’s investigation of the social and moral conditions of the Indian army, and in that role she opened and supervised a rescue mission for camp followers. Patterson also taught obstetrics at the North India College of Medicine. In 1906, she married meteorologist and fellow Ontarian John Patterson. The couple returned to Toronto in 1910 with their infant son, Arthur. Patterson did not continue her medical practice in Toronto, but instead devoted her considerable energy and skill to reform politics and social service. In addition to her work with the Toronto Local Council of Women, Patterson organized and provided training to Red Cross, St. John’s Ambulance, and other voluntary health initiatives, as well as lecturing widely.

With Patterson as magistrate, the jurisdiction of the Women’s Court was expanded to include all “domestic relations” cases as well as all criminal matters in which women were accused and all sexual offences in which women were involved, including as victims. This meant that women appeared before the court not only as defendants but also as complainants in both criminal and domestic cases, and the Women’s Court was one forum – perhaps the only – in which women could find redress for various wrongs done to them.

In domestic relations cases, Patterson saw her role largely as one of mediator, and her primary aim as the reconciliation of families. In 1925, she wrote, “Some idea of the extent of the work in this Court may be gained from the fact that during the past year over sixty thousand dollars was collected from husbands who were trying to shirk their duty. The chief object of this Court, however, is not to collect money but to re-establish homes, and much valuable work has been done in this connection and many families re-united.”[6] Patterson’s vision of harmonious family life explicitly embraced marital equality and emphasized the need for partnership between husband and wife.

In criminal matters in which women were defendants, Patterson saw herself as a reformer and she was critical of short sentences that punished offenders without addressing the causes of crime. In an article entitled “Care of Criminals,” Patterson wrote: “The police records show that the same people come before the court again and again, and each time more confirmed criminals than before. The sentence is given as punishment, not as a means of reform. The trouble with our present system is that we think only of the offence, and not of the offender. We deal with cases, forgetting that each case represents a human being with an immortal soul.”[7]

Although Patterson was praised for her “kindly and sympathetic judgment,” her focus on reform frequently led to the imposition of sentences that offenders likely experienced as neither kindly nor sympathetic. In particular, Patterson was a proponent of the indeterminate sentence. Rather than a fixed period of time – for example, six months imprisonment on conviction for theft – an indeterminate sentence allowed a magistrate to impose a sentence of up to two years less a day, with the length of that sentence to be determined by the offender’s conduct in jail. In effect, offenders could earn “early” release through good behaviour, which was understood to demonstrate that they had been rehabilitated. On the other hand, offenders who would not or could not comply with prison rules and requirements often served sentences far longer than would ordinarily have been imposed given the nature of the offence. Although there have been significant changes to the criminal law over the decades since, Patterson’s focus on the offender rather than the offence continues to resonate today and finds a modern echo in risk-based approaches to sentencing and conditions of incarceration.

Patterson’s term as magistrate of the Toronto Women’s Police Court came to an end in 1934. The newly elected Liberal government restructured Ontario’s court system and advised Patterson that she was to be replaced as magistrate of the Women’s Court by Thomas O’Connor, KC (who, it may be noted, was paid nearly twice the salary Patterson had received). Patterson was offered a position as a Justice of the Peace, but declined what she viewed as a demotion. The Women’s Court itself closed shortly thereafter.

Although the Women’s Court was a short-lived and imperfect attempt to respond to women’s needs in relation to both criminal and family law, it demonstrated the availability of alternative approaches to the administration of justice and helped pave the way for future reforms. Patterson’s approach to domestic relations cases was an important precursor both to modern family law and to the work of the Family Division of the Provincial Court, created in 1968.

- Amanda Glasbeek, Feminized Justice: The Toronto Women’s Court 1913-1934 (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2009) p. 1. ↩

- “Magistrate Patterson On Advantages Of Women’s Court” Ottawa Citizen March 26,1926, p. 13. ↩

- “Magistrate Patterson On Advantages Of Women’s Court” Ottawa Citizen March 26,1926, p. 13. ↩

- Glasbeek, Feminized Justice, p. 13. ↩

- Glasbeek, Feminized Justice, pp. 34-35. ↩

- Margaret Patterson, “The Women’s Court of Toronto,” Social Welfare 10 (July 1925) p. 188, cited in Glasbeek, Feminized Justice p. 42. ↩

- Margaret Patterson, “The Care of Criminals,” in Social Service Congress, Annual Report of Addresses and Proceedings (Ottawa, n.p., 1914) pp. 226-30, cited in Glasbeek, Feminized Justice, p. 62. ↩

Colonel George Taylor Denison

While Margaret Patterson was the first woman to preside in Toronto’s Women’s Court, she was not the first magistrate to serve in that role. Colonel George Taylor Denison took that honour when the first cases were heard Women’s Court opened its doors in 1913. Appointed a police magistrate in 1877, Denison retired in 1921 – and Patterson took his seat on the bench.

One of the most sensational matters to come to the Women’s Court involved an 18-year-old maid. In 1915, a member of one of Canada’s wealthiest families was killed by a young domestic servant. Charles “Bert” Massey was shot by Carrie Davies, a British immigrant working as a maid in the Massey family home. In the language of the day, Massey had made “improper proposals” to Davies. On February 9, 1915, Denison presided over a courtroom in Old City Hall, and remanded the woman to the Don Jail. On February 16, Davies returned to appear before Denison in the Women’s Court. At that time, she was formally charged with murder and the case moved to the Ontario Supreme Court (High Court Division). Rendering a decision which stunned Torontonians, the jury, at trial, found Davies not guilty of the murder of her employer. In The Massey Murder, author Charlotte Gray offers her colourful take on the crime, the trial, Denison himself, the workings of the justice system of the day, and the Toronto over which Denison so firmly presided for 44 years:

Magistrates in England and Canada were often referred to as “beaks,” but in Toronto there was only one court official who was invariably called “The Beak,” and he was a favourite of the Press Gallery. Denison was the unchallenged monarch of City Hall’s police courts. One journalist had recently written that a trip to Toronto without visiting a Denison courtroom “would be like going to Rome and not seeing the Pope.”

Police Magistrate Denison stood for everything that was most British about Canada in 1915…

Before becoming the police court magistrate, City Hall’s Colonel Denison saw service in the militia against the Fenians at Ridgeway in 1866 and the Metis and Indians during the Northwest Rebellion in 1885. He had also made himself an authority on military tactics, especially the élan of the cavalry charge: in 1877, he had travelled to Moscow to receive an award from the Russian tsar for his book History of Cavalry. This Colonel Denison’s most passionate commitment was to Canada’s destiny as an integral part of the British Empire: chief organizer of the United Empire Loyalists and president of the British Empire League in Canada, he crossed the Atlantic frequently to remind British politicians of the importance of Empire in Canada, and Canada to Empire…

All in all, Colonel George Denison was a nineteenth-century figure increasingly at odds with the twentieth century. But he was not alone in a Toronto that, despite the city’s rapid growth, was still run by a Protestant elite of families who flaunted their British origins…

Boasting that he presided over “a court of justice, not a court of law,” (Denison) cantered through cases at a breathtaking pace, relying more on intuition than evidence, and flaunting his impatience with legal technicalities and procedural niceties. Denison handled an average of twenty-eight thousand cases a year, which, according to Harry Wodson, police court reporter for the Evening Telegram, constituted an astonishing caseload of over five hundred a week. To the exasperation of the magistrate’s seven clerks, Denison routinely cleared his docket in a couple of hours before lunch, ordered the court adjourned, and then, stick in hand and homburg hat on head, strolled off to the handsome dining room of the National Club, at 303 Bay Street.

In Denison’s court, people who “knew their place” (retired soldiers, hard-working British immigrants, and the penitent) could expect leniency. In contrast, striking workers, people of Irish or African-American descent, and the nouveaux riches found little mercy. Admirers like Harry Wodson, who shared Denison’s outlook, thought he was a terrific fellow: “A swift thinker, a keen student of human nature, the possessor of an incisive tongue, he extinguishes academic lawyers, parries thrusts with the skill of a practised swordsman, confounds the deadly-in-earnest barrister with a witticism, [and] scatters legal intricacies to the winds… His mind is more or less remote from the affairs of the rank and file of humanity… Just what mental process is used to make the punishment fit the crime, only the magistrate himself knows.” But Denison infuriated those who regarded him as a whip-cracking fossil, mired in the assumptions of a borrowed class system. Phillips Thompson, a journalist and labour sympathizer who worked on the publication the Western Clarion, excoriated the magistrate in print: “He is true as hell to the ideals of his Tory U.E. Loyalist ancestors, and holds like them that all popular notions of liberty are rank delusions and that the masses were bound to be exploited for the benefit of the ruling class.”

Denison had no interest in what drove individuals to break the law. One woman whom he regularly fined for drunkenness amused Harry Wodson by reproaching the magistrate: “The only diff’rence between me and Lady O’Flaherty up in Rosedale is that I have no powdered flunkeys to carry me up to bed whin I’m drunk.” Denison paid no attention and sent her to the slammer.

Only a sense of humour softened Denison’s paternal Toryism and patrician bias. He filled scrapbooks with cartoons of himself (he was easy to caricature), and Harry Wodson enjoyed watching the Beak suppress a chuckle at the cheeky remarks from court regulars. Dodson suggested that his genial manner endeared him to most defendants who appeared before him. A 1913 cartoon pictured a tattered husband and wife jostling each other in front of Denison’s seat, and the woman saying to her husband, “Ain’t I got as much right to enjoy the pleasure of bein’ tried by Colonel Denison as you have?”

(Gray, Charlotte. The Massey Murder: A Maid, Her Master, and the Trial That Shocked a Country (Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. for the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 2013) pp. 23-28. Reproduced with the permission of the author.)

Three Chief Magistrates

Three Chiefs in Four Months

Johnstone L. Roberts

(The Ottawa Journal, Friday, June 12, 1964, p. 25)

Frederick W. Bartrem

(The Ottawa Journal, Saturday, September 19, 1964, p. 34)

Arthur O. Klein

(The Ottawa Journal, Saturday, October 24, 1964, p. 11)

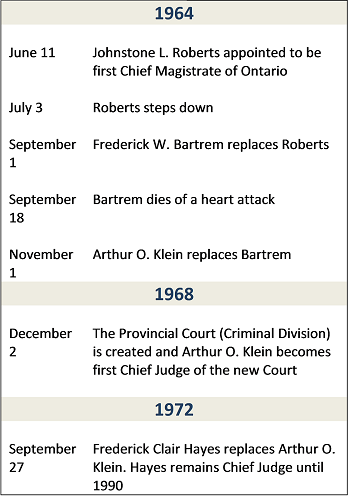

On June 11, 1964, the Ontario government appointed Johnstone L. Roberts to be the first Chief Magistrate for Ontario. This historic appointment was made possible by amendments that year to The Magistrates Act. The amendments created the new position with “general supervisory powers over arranging the sitting of magistrates and assigning magistrates for hearings, as circumstances require.”[1]

Approximately three weeks after his appointment was announced, Roberts stepped down, citing health reasons. On September 1, 1964, the government appointed Frederick W. Bartrem. Sadly, Bartrem died of a heart attack two and a half weeks later.

On November 1, 1964, the government appointed Arthur O. Klein to replace Bartrem. Klein had a much longer run than his two predecessors, serving as Chief Magistrate for four years. He then became the first Chief Judge of the new Provincial Court (Criminal Division), a post he held for another four years following the enactment of The Provincial Courts Act in 1968.

In 1972, Klein returned to government, serving as Crown Attorney for Metro Toronto. Fred Hayes was appointed as Chief Judge (Criminal Division), remaining in that position for 18 years until the Court was restructured as the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) in 1990.

Johnstone Llewellyn Roberts

Before his appointment to Magistrates’ Court, Johnstone Llewellyn Roberts was a well-respected magistrate in Niagara Falls. Criminal defence lawyer Edward Greenspan, also from Niagara Falls, recalls how Roberts stood out as a fine jurist whose decisions were occasionally reported in the Canadian Criminal Cases, a rare occurrence at the time for the magistrates’ bench. [2] Roberts also served as a juvenile and family court judge.

Born in 1919, Roberts was only 33 when he became a magistrate – “the youngest magistrate ever,” reported The Toronto Daily Star.[3] A lawyer, he had served four years in the navy during the Second World War – and was discharged as a sub-lieutenant.

He stepped into a difficult job as the first chief. “Old City Hall first problem for new chief magistrate” blared the headline in The Toronto Daily Star, announcing his appointment. He will “find his desk stacked high with problems when he takes over,” read the Star.[4] Among those problems? The Old City Hall had just been vacated by municipal politicians – and there was considerable wrangling about who would move in and when. It was to be split between police headquarters and the courts but the decision had been made that it was too small to accommodate both.

Roberts was also under pressure from the Attorney-General Arthur Wishart who was quoted in the Star article stating: “[O]ne of Mr. Roberts’ main duties will be to introduce uniformity of sentencing principles across the province.” That comment sent Roberts to the barricades on behalf of judicial independence – he fought back with these words, also quoted in the Star piece: “Mr. Roberts, in a telephone interview stressed that ‘it is not my job to interfere with the individual magistrates.’” The battle lines were drawn.

Interestingly, Roberts saw no conflict between his position as an “independent” magistrate and his significant relationship with the police. As Chief Magistrate, he was set to serve as a police commissioner for Metro Toronto (although he resigned before he could be sworn in), in addition to also serving as a member of five police commissions in his home county of Welland.

A “Reported” Case, Decided by Chief Magistrate Roberts

R. v. Mingle [1965] C.C.C. 172 was a case decided by Chief Magistrate Roberts subsequently reported in the Canadian Criminal Cases. Only those cases which deal with significant points of law are considered to be valuable precedents and included in law reports. The case involved the serious injury of a young woman sitting on a bus. A bottle, thrown through the door of the bus, hit her. Only one of the six Crown witnesses swore that it was the accused – Mr. Mingle – who threw the bottle which injured the young woman. The best description the witness could give was that the bottle thrower had “kind of light brown hair” and was about 5’4” or 5’5” tall. Chief Magistrate Roberts acquitted the accused relying on an earlier Nova Scotia court judgment: “Unless the witness is able to testify with confidence what characteristics and what ‘something’ has stirred and clarified his memory or recognition, then an identification confined to ‘that is the man’, standing by itself, cannot be more than a vague general description and is untrustworthy in any sphere of life where certitude is essential.”

Frederick W. Bartrem

Very little is known about Frederick Willard Bartrem. Like Roberts, he too was a lawyer, called to the Ontario Bar in 1926. He was appointed a magistrate on May 1, 1954. He died at 63, just 18 days after assuming the duties of Chief Magistrate, collapsing of a heart attack in his offices at the Willowdale Magistrates’ Court.

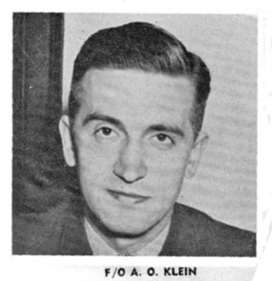

Arthur Otto Klein

Flying Officer and Lawyer

According to newspaper reports, Arthur O. Klein was born in Walkerton, Ontario in 1907. Appointed assistant Crown Attorney in 1945, he handled many high profile cases, including 50 charges of murder. In three of the murder cases he prosecuted, the convicted persons were hanged – among the last so punished in Ontario. Klein also received significant media attention for his prosecution of municipal officials in York Township.[5] He had practised law in Brantford before joining the Department of the Attorney General of Ontario.

When Klein assumed the position of Chief Magistrate, his first order of business was modernizing the Court. “At present, our courts are a maze of antique facilities which are quite inadequate. I have every hope for some improvement in the next year, ” he told the Toronto Daily Star.

A Flying Officer, Klein served the Royal Canadian Air Force, starting in July 4, 1941, in Halifax, Uplands and Trenton.[6] After serving as Chief Magistrate, he became the first judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division), following the creation the Provincial Courts in 1968 and the repeal of The Magistrates Act.

A Laid-Back Chief

It appears that Klein had an informal leadership style. In his memoir, Judge David Vanek recalls his swearing in as a magistrate by Chief Magistrate Klein in 1968:

“The swearing in was far from the elaborate ceremony and social affair it became later. It happened without prior notice one morning when I was seated beside the Chief Magistrate, having a cup of coffee with the other magistrates, at a long rectangular table in the room (in the Old City Hall) that became known as the judges’ common room. Arthur Klein casually turned toward me and remarked that it was about time I was sworn in as a magistrate. So I took the bible that was handed to me, raised my right hand, the Chief administered the prescribed oath of office, which I affirmed, and I signed a document in confirmation.”[7]

In Vanek’s opinion, Klein was more outstanding as a prosecutor than as administrative head of the Court:

“Arthur Klein had an excellent reputation as a senior assistant crown attorney who had prosecuted some important criminal cases. Unfortunately, he was a disappointment as Chief Magistrate and later as Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). He seemed to have no interest in the work and left the administration of the courts almost wholly in the hands of Fred Hayes who acted as his deputy.”[8]

Return to Government

In 1972, Arthur Klein returned to the Ministry of the Attorney General and Fred Hayes became Chief Judge, a position he held for 18 years. Newspaper reports suggest that Klein’s return to government may have been controversial. Upon his retirement from the Court, Klein was appointed as Crown Attorney for Metro Toronto.

Klein’s appointment was roundly criticized in the press: “The appointment made last week by Attorney General Dalton Bales creates a questionable relationship in the courts of Metro Toronto where Mr. Klein will be directing the prosecution of citizens before courts and judges he has overseen since 1964. It can be argued that the Crown Attorney of Toronto is an administrator rather than a prosecutor, but the final responsibility for all the decisions of the prosecution – what charges to lay, what courts to proceed in, what sentence to seek and what decisions to appeal – are his.”[9]

The main criticisms of the appointment were not levelled at Klein himself – “this is not to questions Arthur Klein’s fairness, competence and ability”[10] – rather the media coverage had its sights set on the Attorney General – Dalton Bales — and casting doubt on his judgment in making the appointment.

- The Magistrates Amendment Act, 1964, s.4 ↩

- Interview with E. Greenspan for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- The Toronto Daily Star, June 12, 1964 ↩

- The Toronto Daily Star, June 12, 1964 ↩

- The Toronto Daily Star, October 23, 1964. ↩

- “Strictly Business,” Contact Trenton (The Official Organ of the R.C.A.F. Station, Trenton, Ontario), p. 6 ↩

- Vanek, David. Fulfilment: Memoirs of a Criminal Court Judge (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 1999) pp. 223-224. ↩

- Vanek, Fulfilment, p. 224. ↩

- The Ottawa Journal, October 4, 1972 ↩

- The Ottawa Journal, October 4, 1972 ↩

Judge S. Tupper Bigelow: A Man of Many Interests

Sherburne Tupper Bigelow was appointed an Ontario magistrate in 1945, bringing with him a lifetime of experience literally from across the country. Born in Truro, Nova Scotia, in 1901, he was raised and educated in Regina. Following law studies at Osgoode Hall and the University of Saskatchewan, Bigelow became a member of both the Alberta and Saskatchewan bars and held the position of crown prosecutor in Edmonton. He joined the RCAF in 1940, then practised law in Toronto and sat on the Toronto Board of Education before being appointed to the bench.

In 1950, Bigelow took on a new challenge, in addition to his duties as a magistrate. He became the first chairman of the newly created Ontario Racing Commission.

When Bigelow was inducted into the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame in 1991, his work for the commission over a 15-year term was described as follows.

The man appointed by Premier Leslie Frost in 1950 to legislate the sport of horse racing in Ontario admitted that all he knew about a horse ‘was what my old riding instructor told us at RMC (Royal Military College).’ As to what the job entailed, Magistrate Sherburne Tupper Bigelow was not quite sure. One of his functions, he knew, would be to cut down bookmaking…. It wasn’t long before the government came to realize that the 49-year-old Bigelow was the ideal individual for his role of correcting many of the problems hindering the growth of both thoroughbred and standardbred racing in Ontario. The early years under the chairman were evolutionary ones for the commission, which was the first one in Canada. One of its first moves was the introduction of the ‘film patrol.’ The motion picture camera, used to film races from several vantage points, enabled the commission to build up a case in a betting-ring scandal in 1951 at Fort Erie, one that saw 10 jockeys and a trainer ruled off North American tracks for life….He served as Commissioner until 1965.

But there’s more. Judge Bigelow was one of the world’s leading authorities on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, from whose imagination and pen sprang the famed sleuth Sherlock Holmes in the pages of four novels and 56 short stories. In 1970, the Toronto Reference Library acquired an extensive collection of Holmesian ephemera from collector Judge S. Tupper Bigelow and the library also published a collection of scholarly Holmesian essays written by Bigelow – The Baker Street Briefs. Bigelow died in 1993.

(Photos and text courtesy of the Canadian Horse Racing Hall of Fame)