The Provincial Courts

Introduction: A Time of Transition

The New Provincial Courts: Reforms from 1968 to 1989

Institutional and Structural Innovations: Judges

Institutional and Structural Innovations: Justices of the Peace

Court Facilities and Accommodations

Work of the Criminal Courts

Work of the Family Courts

The Civil Division of the Provincial Courts

The Impact of the Charter on the Provincial Courts

Conclusion

Introduction: A Time of Transition

Canada began a great transformation in the 1960s, exemplified by the promise of the “Just Society” – a place where injustice and inequality had no place. The era was defined by the struggle for equality rights, and the rise of feminism and multiculturalism. Traditional legal institutions were turned on their collective heads. By the 1970s, courts across the nation were undergoing the “Great Canadian Judicial Revolution.”[1]Criminology departments were launched at Canadian universities, a law reform commission was established by the Ontario government “for the reform of the law and legal institutions,” and the Canadian constitution was amended, in 1982, to include the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

This was a time when the courts that would later become the Ontario Court of Justice experienced a substantial improvement in their status and a similar improvement in the calibre of their judges and justices of the peace.[2] In 1968, the piecemeal collection of magistrates’ courts and juvenile and family courts were consolidated into two new sets of Provincial Courts: the Criminal Division and Family Division. Not only did the structure of the Courts change, but their workload expanded as the Courts were given additional jurisdiction to hear many more types of criminal and family cases.

These advancements were no accident. They came from critical examinations of the state of the courts of the day – and the pressures placed on them by a growing and changing society.

Bookends: The McRuer and Zuber Reports

The period was “bookended” by two inquiries called by the government of Ontario into the workings of the province’s justice system and its courts. Both of these inquiries – the McRuer Inquiry[3] in 1968 and the Zuber Inquiry[4] in 1987 – proposed significant changes to the courts by way of specific recommendations, many of which were acted upon.

While these were the two most significant inquiries, other reviews also occurred and contributed to the re-working of the Provincial Courts.

Continuous and significant reform– though sometimes slow and halting- was the result. Despite the growing professionalization and responsibilities of the Provincial Courts, by 1989, they were still considered by many to be at the low end in the hierarchy of the courts in Ontario. Judges and justices of the peace were daunted by heavy caseloads, often unsatisfactory court facilities, and low remuneration compared to federally appointed judges in the superior courts.[5] They were still seen as administering the “poor law” in the “poor man’s court.”[6]

The Impact of the McRuer Report 1968

Reform was definitely in the air in 1964 when James Chalmers McRuer, then Chief Justice of the High Court for Ontario, was appointed to lead the “Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights.” The McRuer Report had a transformative impact on what had been the Magistrates’ Courts and the Juvenile and Family Courts in Ontario.[7] Even before the release of the report, a bill had been drafted to implement McRuer’s recommendation to replace these courts with what were to be called “Provincial Courts.” A series of reforms was put into motion to address McRuer’s concerns, which included worries about the competence of judicial officials, their judicial independence from the government of the day and the inadequacy of court accommodations.

McRuer delivered his report on February 7, 1968. The Provincial Courts Act, 1968 was introduced into the Legislative Assembly in March 1968, received royal assent on May 30, and came into force on December 2, 1968.[8] In each county, the Magistrates’ Courts were replaced with a Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and the Juvenile and Family Courts with a Provincial Court (Family Division). There were two Chief Judges for the Provincial Courts – one for the Criminal Division and the other for the Family Division. (A Provincial Court (Civil Division) – a “small claims court” – was introduced in 1980, and its judges and jurisdiction were later transferred to the superior court. In 1980, the Provincial Offences Act designated the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) as a provincial offences court, with jurisdiction over all offences under provincial statutes.)

The McRuer Report served as the fundamental point of departure for the modern history of the Court.

Perhaps the most telling comments in McRuer’s report focused on his concern with the “infringement on the basic civil rights” of those coming before the magistrates’ and juvenile and family courts.[9]

The McRuer Report catalogued a litany of serious concerns with these courts.

Among other things, McRuer was critical of the “strong political influence” in the selection process both for magistrates and family judges, inadequate training and qualifications of these judicial officers, and their inadequate accommodations.[10] The fact that many of these judicial officers served part-time and held down other jobs compromised their independence, he stated.[11] An over-close relationship of many magistrates with the police did the same.[12]

McRuer was forceful in his criticism of the justice of the peace system, condemning it outright and calling for the “whole system pertaining to the office of the justice of the peace” to be “reorganized.” All of the appointments of “present justices of the peace” should be cancelled, with only those “qualified for the office” reappointed. Further, McRuer advocated that justices of the peace be “allowed a meaningful share of the judicial work…so as to relieve the magistrates of those duties which appropriately can be performed by well-trained justices of the peace.”[13]

It would take another report – the Mewett Report in 1981 – to stimulate a major reform process for Ontario’s justices of the peace.

Who was J.C. McRuer?

“McRuer was the greatest law reformer this country has ever seen.” Senator Richard Doyle

“McRuer! He was the meanest son-of-a-bitch I ever encountered.” Senator David Walker

Both of these quotes appear side-by-side in author Patrick Boyer’s biography of McRuer, A Passion for Justice: The Legacy of James Chalmers McRuer. Boyer concluded that both senators were correct in their appraisal of the man. Some saw him as a saint, others called him “Vinegar Jim.”

Born in 1890, his legal career spanned more than 50 years and included work on penal reform in the 1930s, an appointment to the Ontario Court of Appeal in 1944 and then as Chief Justice of the Ontario High Court in 1945. During that time, he heard many murder cases and garnered the nickname “Hanging Jim” for sending people to the gallows.

From 1964 to 1971, he was head of the Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights – and produced the McRuer Report. He was also the chairman and later the vice-chairman of the Ontario Law Reform Commission – the first such body in the British Commonwealth – which was created largely through his efforts.

He was passionate that the justice system should serve the oppressed, regardless of their ability to pay. He well understood the changing nature of society in the 1960s and knew that the justice system could be redesigned to better serve the public.

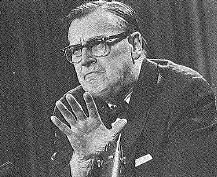

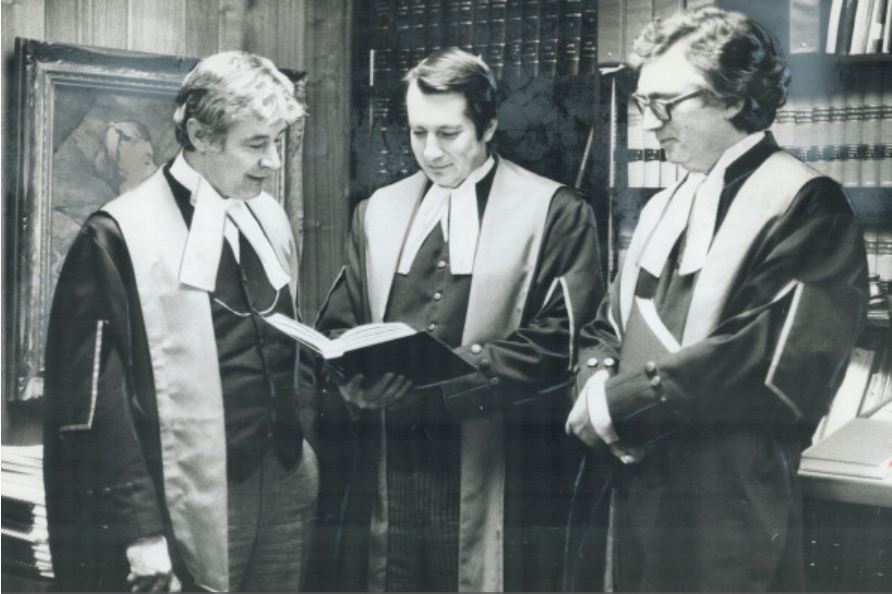

In 1968, McRuer holds a press conference at Queen’s Park to unveil the first three volumes of his inquiry into civil rights. (Photo: Maier, The Globe and Mail)

“Nothing quite like McRuer’s inquiry into civil rights had been seen in Canada before. In a sense, it became a great work of constitutional reform,” wrote Boyer. In his attempt to ensure the rights of ordinary Canadians, he harshly criticized the manner in which justices of the peace, family judges, and magistrates were appointed and – once appointed – administered. And, he offered “bold and refreshing recommendations for change” that served to inform all the reforms to these offices for years to come.

When the McRuer Report was released, commentators called it “a blow for liberty” and predicted its influence would “be felt for the next fifty years.”

(Boyer, Patrick. A Passion for Justice: The Legacy of James Chalmers McRuer (Toronto: The Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History, 1994)

The Recommendations of the Zuber Report, 1987

The Report of the Ontario Courts Inquiry, authored by Justice Thomas G. Zuber, was published in 1987. In many ways, the Zuber Report was a response to the many changes that occurred in the justice system as a result of the McRuer Report, the introduction of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms and many other legislative reforms, and – generally – “changes in society.”[14]

Ian Scott, the Attorney General who appointed Zuber, provided him with “the widest scope to deal with any question that arises in the area of organization, structure, jurisdiction or workload of any court of Ontario.” Scott stated: “Mr. Justice Zuber’s inquiry is not intended to be a mere tinkering with the existing system but rather a fundamental re-thinking of all the assumptions on which our courts have operated since 1792 when they were first established on the creation of the Province of Upper Canada.”[15]

Zuber saw his task as making recommendations to rationalize and simplify the justice system in Ontario – for the benefit of the public it served.[16] Like McRuer, Zuber proposed major changes to the entire court system in Ontario. Zuber’s principal recommendation was, as much as possible, that the various levels of trial courts, criminal and family, in the province be amalgamated into single trial courts. To reduce the complexity of the system, Zuber foresaw the ultimate unification of the superior courts with the Provincial Courts into single criminal and family courts. This recommendation was supported by then Attorney General, Ian Scott, and the Association of Provincial Criminal Court Judges of Ontario.[17] The concept of unified trial courts was strongly opposed by, among others, the leadership of the superior courts and the federal government. Unified family courts had previously been introduced in some jurisdictions in Canada. While a unified criminal court never did materialize, many other significant changes did occur – which changed the face of the Provincial Courts.

The plans ultimately resulted in a wholesale reorganization of the courts in Ontario. These changes were effected by The Courts of Justice Amendment Act, 1989, which came into force on September 1, 1990. The District Courts and the High Court (the trial division of the Supreme Court of Ontario) were merged to become the Ontario Court (General Division). The two Provincial Courts were replaced by the newly created Ontario Court (Provincial Division), with a single Chief.[18]

Calls for Court Reform: The Reorganization of Provincial Courts Begins

The move for reform was on – and agitation was coming from many quarters – for open, fair, and independent courts.

On the heels of the McRuer Report, and before the release of the Zuber Report, came several other reports, including:

- a collection of reports prepared by the Ontario Law Reform Commission in the 1970s, touching on all aspects of the Provincial Courts, judges and justices of the peace,

- “Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on The Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario,” submitted by Professor Alan W. Mewett in 1981 (the “Mewett Report”),

- “Report of the Provincial Criminal Court Judges’ Special Committee,” prepared by the Association of Provincial Criminal Court Judges of Ontario in 1987 (the “Vanek Report”), and

- “Report of the Ontario Provincial Courts Committee,” prepared for the Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General in 1988 (the “Henderson Report”).

All of these reports – like the McRuer Report – recognized the growing importance and professionalization of the Provincial Courts. All were highly critical of the lack of judicial independence, lack of education for judicial officers, and lack of financial supports for both the administration of justice and the Courts’ judicial officers.

The New Provincial Courts: Reforms from 1968 to 1989

The Provincial Courts era heralded a growing awareness of “the need to preserve and protect basic principles relating to the civil liberties, human rights, fundamental freedoms and privileges of the individual inherent in citizenship.”[19] These words are contained in the Order-in-Council that established the McRuer Inquiry, which released the report that so altered the shape of the Provincial Courts.[20]

The courts presided over by provincially appointed magistrates and justices of the peace – already the busiest in the province prior to 1968 – kept getting busier. By the mid-1970s, they were recognized as being “the most important courts in Ontario. The vast majority of our citizens who appear in court make their appearance exclusively in these courts, which have very great powers over the individuals tried in therein.” [21]

The challenges of change were again acknowledged and recognized at the end of this 20-year period. In 1987, the Zuber Report concluded: “It became clear that the problems with the justice system are enormously complex and that there is no quick fix or magic solution. It became apparent that what was needed was a detailed and major overhaul of an extremely complex machine.”[22] Despite the fact that Zuber was calling for significant reforms to the court system in 1987, he – like many others – recognized that many things had changed following the creation of the Provincial Courts in 1968. “Changes which were considered too radical ever to occur were adopted, almost without a murmur, a few years later.” [23]

Reforms during the Provincial Courts era (1968 to 1989) took two fundamental forms:

1. Institutional and structural innovations, including changes to the qualifications, appointment and regulation of judges and justices of the peace, and changes to court accommodations, and

2. The introduction of new laws and other changes which dramatically affected and increased the work of judicial officers of the Provincial Courts.

Institutional and Structural Innovations: Judges

On December 2, 1968, Ontario’s magistrates and family judges were appointed to be Provincial Judges. Many other changes followed.

Positions of Chief Judges, Senior Judges and Associate Chief Judges

The Provincial Courts Act, 1968 created the positions of Chief Judge within each of the two Provincial Courts.[24] Arthur Klein was the first Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). Fred Hayes succeeded him as Chief in 1972 and served until April 1990. Sidney Linden replaced Hayes as Chief and, then, on September 1, 1990, became the Chief Judge of the new Ontario Court (Provincial Division). Ted Andrews served as the first Chief of the Provincial Court (Family Division) and continued in that position until September 1, 1990 when that Court became part of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division).

The 1968 Act also provided for the designation by the Attorney General of Senior Judges within the 10 regions into which the province was then divided.[25] These Senior Judges were to assist the Chief Judges in their work – although there were often times when certain regions were without Senior Judges.[26] The Provincial Courts Amendments Act, 1977 provided for the appointment of an Associate Chief Judge in each of the two Provincial Courts.[27] In September 1978, Robert Walmsley was the first judge appointed as an Associate Chief for the Family Division. Harold Rice was the first judge appointed to this position for the Criminal Division.

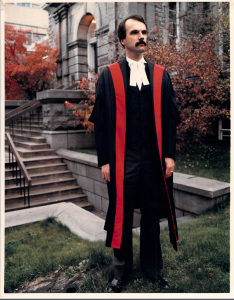

Arthur Klein, shown here with his family, served as the first Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). (Photo: Getty Images)

Associate Chief Justice Harold Rice

Harold Rice was known as the man who “would smooth the waters and make sure that everyone would be happy.” Appointed to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in 1971, he became the first Associate Chief Justice of that Court in 1979. As the Court grew in the 1980s and became busier, Rice initiated a system to manage cases at Old City Hall in Toronto. In addition, he served as a mentor to newly appointed judges of the Criminal Division – many of whom received their initial training at Old City Hall.

(Source: Benchmark, A Newsletter for the Judges of the Ontario Court of Justice, Vol. 9. No. 2, Spring 2000, p. 1)

The structure of the Courts was described as “loose.”[28] According to the Provincial Courts Act, 1968, [29] the Chief Judges could supervise and direct the sittings of the Courts and assign judges for hearings.[30] This limited definition of the functions of the Chiefs was criticized. Who had responsibility for education of judicial officers? Who established guidelines on policy matters with a view to encouraging uniformity of judicial practice? Who had the responsibility for assigning justices of the peace? In fact, the Chiefs, senior judges, and Associate Chief Judges did these tasks – but in an ad hoc fashion, with a limited budget over which they had no control, and very little administrative support.

When Fred Hayes was Chief Judge of the Criminal Division, he had an office in Toronto’s Old City Hall and was supported by one administrative assistant – even though, at the beginning of his tenure in 1972, over 2,000,000 cases were disposed of in the Provincial Courts (Criminal Division) and he was responsible for the assignment of more than 120 judges.[31]

Former Chief Justice Brian Lennox, who was appointed to the Court in Ottawa in 1986, confirmed that loose approach to the Court’s structure. “Chief Judge Hayes had taken a fragmented criminal Court in 1972 and was moving it towards a more organized and systematic institution. However, when I was appointed in 1986, my experience was that local judges and local courts operated with a great deal of individual autonomy and with little interaction from the office of the Chief Judge,” Lennox recalled.

A Day in Court with Judge June Bernhard, March 1985

Judge June Bernhard made history in 1979 when she was appointed the first female judge on the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). She held her own, however, joining the “brotherhood” at Toronto’s Old City Hall and, as detailed by author Jack Batten in his book, Judges, earned the respect of the legal community. This excerpt from Judges, not only provides a glimpse into the typical daily work of a criminal court judge, it also gives a good sense of the empathy June Bernhard brought to her work.

Judge June Bernhard grimaced. For her, a grimace is a rare expression. She’s more frequently seen with a smile in her courtroom. She smiles in court more than any other judge in Old City Hall, an appealing smile that springs from neither contempt nor derision. In her late fifties, Judge Bernhard is petite and dark-haired and has a slight overbite that gives her smile an attractive cast. She smiles in an understanding way when she is debating a legal point with counsel. She smiles in encouragement when she’s questioning a confused witness. The smile is a reflex, and it’s indicative of a judge whom defence counsel and crown attorneys respect for her generosity and kindness. But on this March 1985 day, in Thirty-three court, not liking what she was hearing, Judge Bernhard grimaced.

She was conducting a robbery case. The accused man, husky with a gloomy face, had gone into a variety store and told the young woman behind the cash register he was packing a gun and wanted the store’s receipts. The girl called for her father, the proprietor of the store, and when he appeared, the man threatened to kill him. The store owner handed over five hundred dollars, and the man vanished down the street. He was arrested nine days later. The police had no difficulty getting a line on the man. He had been released from prison only a few months earlier on mandatory supervision from a nine-year sentence for another robbery. In court, the accused man’s defence counsel told Judge Bernhard that his client had no skills, no job prospects, no money. All he had when he came out of prison was afondness for drink and drugs and a sense of hopelessness. “He slipped back into crime,” the defence counsel said. The crown attorney said that the accused man was “part of the revolving-door syndrome,” out of prison, into crime, and back to prison. Judge Bernhard grimaced and sentenced the man to another four and a half years in prison.

“It’s not the kind of case I enjoy,” Bernhard said later, “Nobody gets any pleasure or challenge out of that kind of awful predicament.”

(Source: Jack Batten, Judges (Toronto: MacMillan of Canada, 1986), pp. 90-91)

Appointment and Removal of Judges

The 1968 Act provided for the appointment of “such provincial judges as he (the Lieutenant Governor in Council) considers necessary” to sit in the provincial courts and also provided for the removal of a judge “only for misbehaviour or for inability to perform his duties properly.” [32]

The Act also provided for the creation of a “Judicial Council for Provincial Judges” to perform two functions:

1. To consider, at the request of the Attorney General, the proposed appointment of provincial judges, and

2. To receive complaints of alleged misconduct by provincial judges and conduct inquiries into those complaints.

In the event the Judicial Council recommended a public inquiry into such a complaint, that inquiry was to be conducted by a judge of the Supreme Court of Ontario.[33]

These changes were a great leap forward for the independence and reputation of the Court, providing a formal process to deal with appointments and removal from the bench.

Previously, magistrates and family judges served “at the pleasure” of the government which meant that they could, in theory, be removed without cause. In fact, until the 1968 Provincial Courts Act, in the first two years of their tenure, judges could be removed from the bench at the whim of the government.[34]

What constituted “misbehaviour” of a judge?

Despite several Commissions of Inquiry into complaints about judges, there was never a concrete definition of what constituted “misbehaviour” in s. 4(1) of the Provincial Courts Act.

It was clear, however, that misbehaviour sufficient to remove a judge under the Act did not, however, need to be confined to the judge’s judicial duties.

In the 1978 Commission of Inquiry respecting Provincial Judge Harry J. Williams, the Commissioner, Justice Sydney Robins expressed the view that a judge must respond to a higher standard of conduct in his personal life than required of other citizens. In his report, he wrote:

“His misbehaviour, even if it is in his private life, can damage that essential sense of trust and thus adversely affect his judicial work and the justice system.”

He went on to say that: “Each case must ultimately depend on the nature of the conduct, all the facts surrounding it, its effect on the judge’s ability to perform his official duties, and the extent to which it has impaired public confidence in the judge and in the administration of justice.”

(Source: Justice Sydney Robins, Commission of Inquiry Re: Provincial Court Judge Harry J. Williams, 1978)

The Judicial Council appointment process set out in the 1968 Act went some way to alleviating the whiff of patronage that had accompanied many appointments to the former Magistrates’ and Juvenile and Family Courts.

In 1988, the Attorney General acted on the 1973 recommendation of the Ontario Law Reform Commission and announced the establishment of a three-year project setting up an independent, multi-disciplinary body – the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee (JAAC) to select and recommend candidates for appointment as a provincial judge.[35] The Attorney General could only make recommendations to Cabinet for judicial appointment from the list of candidates provided by JAAC. JAAC was not a statutory body until 1994.[36]

The “Lay-dominated” Judicial Advisory Appointments Committee (JAAC)

Attorney General Ian Scott announced the establishment of JAAC in the Ontario Legislature on December 15, 1988. At that time, Scott told the legislature that JAAC would be “lay-dominated,” (which meant that the majority of its members would be non-lawyers) with members from different parts of the province. He hoped that such a committee would “ensure that the justice system reflects the needs, the values and the attitudes of the community as a whole” and that it would “do a great deal to remove any unwarranted…political bias or patronage in appointments to the judiciary while enhancing community and public involvement and reinforcing confidence in the judiciary and the justice system.”

(Hansard, Ontario Legislative Debates 6835 (15 December 1988))

Qualifications of Judges

The 1968 Act did not require judges of the Provincial Courts to be lawyers. In fact, there were no minimum qualifications required in 1968. However, no judge could preside over a trial sitting as judge alone for an indictable criminal offence unless he or she had been a member of the bar for at least five years, or had acted as provincial judge for five years, or had been a full-time magistrate or judge of the Juvenile and Family Court prior to December 2, 1968. As a result, the practice had developed during the late 1960s to appoint lawyers to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). A similar practice had developed for the Family Division.

By 1973, for example, 108 of 123 provincial judges in the Criminal Division were lawyers.[37] By the mid-1970s, as the workload and complexity of cases was increasing in the Provincial Courts, calls were coming for all new appointments to be legally trained.

The practice of appointing only lawyers as provincial judges was formalized with the Courts of Justice Act, 1984 which stipulated that “no person shall be appointed as a provincial judge unless he or she has been a member of the bar for at least ten years.”[38]

Part-time Judges

The practice of appointing part-time judges, who were also working in other careers, was phased out. Instead, the Court began to rely on judges who had retired from the Court and were subsequently appointed as per diem judges, sitting on a part-time basis. The system was fully detailed in the Courts of Justice Act, 1984, in the provisions concerning “continuation of judges in office” after the age of retirement (65).[39]

Judicial Independence

The concept of judicial independence – that judges have “complete liberty to hear and decide the cases that come before them”[40] – was an integral part of the heritage of the Provincial Courts. The concept received a significant review by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1985 in R. v. Valente [41], a case that got its start at a trial in the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). The Charter had come into effect in 1982 and it provided that any person charged with an offence has the right to be tried by an “independent and impartial tribunal.”[42] In Valente, the Supreme Court decided that Provincial Court judges had sufficient judicial independence and set down the three requirements for judicial independence:

• Security of tenure,

• Financial security, and

• Institutional independence in a court’s administrative matters relating to judges.

Valente added fuel to the fire of an already heated discussion between the judges and the government on the issue of financial security.[43] Provincial Courts Committees were established by the government to make recommendations concerning the remuneration of judges. In 1988, one of those Committees concluded that:

• The compensation for judges should be determined and provided “separately from the usual theatres of government activity,”[44] and

• “The salaries and pensions of judges shall be adequate, commensurate with the status, dignity and responsibility of their office.”[45]

Judicial Education

Led by the efforts of Ted Andrews, Fred Hayes, the Association of Provincial Criminal Court Judges of Ontario and the Association of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, formal continuing education of all judicial officers became recognized as an essential element of a judicial career. As Judge David Vanek wrote about this time, “…successive governments had been responsible for the enactment of a huge amount of legislation that added enormously to the importance and burden of work in the Provincial Court. Amendments to the Criminal Code on a variety of topics brought forth an entirely new spectrum of charges and defences. Provincial Court judges were being called upon to hear and determine issues of a very high order of complexity. Educational courses were necessary to keep the judges abreast of developments in the law and the educational conferences became more focused.”[46]

A New Name Adds Dignity?

“The dignity of our Magistrates has now been enhanced by the designation of Provincial Judge – instead of being addressed as “Your Worship,” they are now accorded the dignity of “Your Honour.”[47] This was written in 1969 by a Supreme Court judge, Donald Keith. Was he correct?

Despite many structural changes to the Provincial Courts via the Provincial Courts Act, 1968 and the Courts of Justice Act, 1984, some might have wondered if much had really changed for the judges.

“Despite the changes effected in 1968, the status of the Provincial Courts…remains low,” concluded the Ontario Law Reform Commission in 1973. “One of the best indications of the low status of the Provincial Courts is the continuous failure to allocate resources to those courts consistent with their obvious needs….The factors which are integral to the concept of a ‘lower court’ are the very factors which demand that greater attention be given to that court in terms of resources and facilities. Some of these factors are the number of people affected by these courts, their broad jurisdiction and the resulting voluminous caseload.”[48]

Importance, volume, jurisdiction and complexity of legal matters continued to grow – yet status remained low.

In 1988, the Henderson Report concluded “it takes a special kind of lawyer to flourish as a judge of the Provincial Court,” and summarized the lot of the Provincial Court judge at that time:

“Because it is so important, the Provincial Court must be in every sense more accessible to the people of the province than are the higher courts. It is, accordingly, in session much more frequently, and in far more locations, than the other Ontario courts; its procedures are more informal, streamlined and flexible, and proceedings before it are typically much less expensive than before higher courts. Although legal representation is increasing before the Provincial Court, judges must still be able to deal fairly and simply with numbers of people who appear without counsel.

For these reasons, the life of a Provincial Court judge can differ in several respects from that of a judge on a higher court….in the Provincial Court one sometimes finds a rawness, even a desperation, rarely found in other courts. Because the Provincial Court’s primary purpose is to deal in volume with cases the system expects will be legally straight-forward, the work of a Provincial Court judge historically has drawn heavily on common sense and basic good judgment. In the past several years, however, complex regulatory matters, more aggressive defensive tactics and the introduction of the Charter of Rights have transformed the Provincial Court into a forum where legal decisions are required to be more sophisticated. Because of the relentless accumulation of matters that come to the Provincial Court for disposition, judges in that court almost never have the luxury of in-depth legal research or reflection about the merits of particular cases. In making most of their decisions, they must rely heavily on their accumulated intellectual capital, for there is limited opportunity for detailed assistance from counsel. And, not least, when Provincial Court judges have to travel – as many do, particularly in the north, they do not go to county towns but to more remote locations, which often lack such basic perquisites as a courtroom or a private room in which a judge may robe.”[49]

Up to Winisk: Judge Gérard Cloutier’s Memories of Fly-in Courts

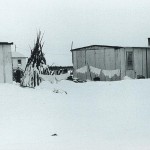

The photos above detail Judge

The photos above detail Judge

Gérard Cloutier’s time in the

North, with a focus on fly-in

court sittings in Winsk.

(Courtesy: G. Cloutier)

Following his appointment to the Provincial Court in 1977, Judge Gérard Cloutier began regular fly-in trips to hold court in the most northerly communities in Ontario, including Moosonee, Attawapiskat and Fort Albany. “About once or twice a month, I’d fly up north. It depended on the list of cases in each community and I also couldn’t neglect my regular circuit of Kapuskasing, Cochrane, Smooth Rock Falls, Hornepayne and Hearst,” recalled Cloutier.[50]

“In the early days, we flew into remote communities in float planes and once airports were built, we’d fly in on Otters and Beavers. In the 1970s and 1980s, everybody went in on one plane, including the Cro wn Attorney, Legal Aid lawyer, defence attorneys, court staff and the court reporter. After receiving complaints from those living in these communities, the government decided this wasn’t right. The independence of the judiciary was at issue and after that the judges travelled alone with court staff and the court reporter.”

“In the winter months, we’d be met upon landing by snowmobiles. I can tell you they weren’t Cadillacs – the ride was very cold and very rough, often over large boulders on river beds. The first time I travelled north, I thought we’d be going into an airport hangar. So I dressed like a city slicker in a light winter coat and toe rubbers. I was so cold I had to hold onto the others I was travelling with to keep warm. It took me two weeks to thaw out. After that I went out and bought a skidoo suit and good boots. I was prepared from then on.”

“We always travelled with sleeping bags, a bit of food and a survival kit. Sometimes we’d get fogged or snowed in and then we’d have to spend the night on the floor of a Legion Hall or a school.”

Winisk was as far north as we in the north-eastern region of the province went.” When he began his journeys north, the “Winisk” in which Cloutier sat was a Cree community on Hudson’s Bay near the mouth of the Winisk River. It was also home to Royal Canadian Air Force Station Winisk, a radar control station from 1958 to 1965. In 1986, Winisk was flooded and the population of about 200 was forced to abandon the town and relocate 30 kilometres up river to higher ground. The town is now called Peawanuck and is still served by the judges of the Ontario Court of Justice who fly in regularly. In 2014, the Court sat on three separate occasions in Peawanuck.

When Cloutier began flying into Winisk – in the late 1970s and early 1980s – Court was held in a community hall or school room. Cloutier recalls his first time presiding in Winisk in a community hall – he had to serve as janitor first, cleaning up garbage and setting up chairs to accommodate spectators. Like other judges who flew into these remote places, Cloutier’s job as judge also involved working closely with Chiefs and Band Councils of these communities. Often, the Chief of a community would sit beside the presiding judge and speak directly to the accused person about the penalty being imposed.

“Often cases were minor – a person driving a skidoo hit someone, or maybe minor assaults, or charges of being drunk in a public place. But sometimes they were serious – domestic violence or a person attacking another with an axe, for example.”

“It was not an easy life,” stated Cloutier. “But I tried very hard to resolve situations fairly and justly.”

(Source: Interview of G. Cloutier for OCJ History Project, 2014)

Institutional and Structural Innovations: Justices of the Peace

The Justice of the Peace System and the Mewett Report – “Urgent Need for Reform”

One cannot read the Mewett Report, published in 1981, without imagining its author – Professor Alan Mewett – sputtering in anger, apoplectic as he wrote sentences like this one about the justice of the peace system in Ontario: “The system is hopelessly confused and unnecessarily complex.”[51] Or these: “It gives me great concern that the duties and functions of the Justice of the Peace are not always clearly understood by those involved in the criminal justice system – by the public, the police, Crown Attorneys, and even judges, to say nothing of government officials. Indeed, I am not at all sure that all Justices of the Peace fully understand their own duties and functions.”[52]

“The JP’s Awesome Power”

The Attorney General’s request for Professor Alan Mewett to inquire into the structure of the office of the justice of the peace had been preceded by calls from the media dating back many years.

In 1966, The Globe Magazine called the office of the justice of the peace a “longstanding, province-wide, judicial mess.” It described the situation of the justices of the peace as “a patchwork of convenient practice, statutory clutter, responsibilities-by-extension, and duties-by-default…a scandal in the purest sense of the term: a stumbling-block to final faith in the due process of the law.” The author, Albert Warson, wrote of justices of the peace signing blank arrest warrants and “rubber stamping traffic summonses” in order to gain the fees associated with issuing them. He criticized the fact that no qualifications were required to become a justice of the peace and no formal training once appointed.

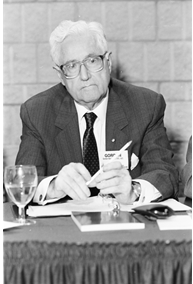

Justice Gerald Lapkin – who would become responsible for the justices of the peace as the first Coordinator of Justices of the Peace in 1990 – recalled that critical articles like Warson’s were not unusual at this time.

(Warson, Albert. The Globe Magazine, February 1, 1966, p. 6; Interview of G. Lapkin for OCJ History Project, 2014.)

It was Alan Mewett’s task – one he undertook with great relish – to determine why the justice of the peace system was in such a bad state and, then, to propose solutions to the problems – and he identified plenty of them. His work – “Report to the Attorney General of Ontario on the Office and Function of Justices of the Peace in Ontario” – was delivered to the Attorney General, Roy McMurtry, in 1981. The vast majority of its recommendations, however, were not acted upon until the 1990s.

The Role of the Justice of the Peace in the 1980s

Writing in 1981, Professor Alan Mewett provided a short outline of the role and importance of the office of the justice of the peace in Ontario:“It has been easy, over the past 100 years or so to downplay the role of the justice of the peace while at the same time burdening him with more and more responsibilities…Justices of the peace…perform a large number of functions and without them the system as we know it would collapse.

They try cases, subject to their jurisdiction, where there is not a guilty plea; they bear the brunt of disposing of the guilty pleas or guilty with an explanation pleas; they may adjourn cases in the absence of a judge; they often deal with the large numbers of failures to appear; they handle a great deal of the bail applications and the accompanying administrative problems; they are in constant demand for swearing affidavits for various purposes essential to the administration of criminal justice; they must consider search warrant applications and decide whether to issue search warrants; they must receive criminal process informations, and decide whether to issue process; they must confirm or cancel appearance notices or promises to appear; they spend much of their time on parking and highway traffic violations; they provide over-the-counter advice for private informants….

The functions now performed by justices of the peace can be broadly categorized as the adjudicative (including trials, sentencing and so on), the bail processing, and the criminal process-issuing (including search warrants, signing affidavits, etc.)….

The justice of the peace is the person who stands between the individual and the arbitrary exercise of power by the state or its officials.”(Mewett Report, pp. 38-39)

Setting out the History of the Office of Justice of the Peace

Mewett premised his report on two previous ones which dealt with the office and functions of justices of the peace in Ontario:

- The “Ontario Royal Commission Inquiry into Civil Rights” (the McRuer Report[53]) published in 1968; and

- The “Ontario Law Reform Commission Report on the Administration of Courts,” which contained a chapter on justices of the peace and was published in 1973.[54]

Changes Resulting from McRuer Report

McRuer had recommended “a fresh start” for the office. He had condemned appointments as a political reward and recommended that all previous commissions be cancelled and the province start anew.[55]

That hadn’t happened by the time of Mewett’s report. McRuer was highly critical of the payment of justices of the peace on a piece-work basis, elaborating: “The fee system is a real inducement to justices of the peace to curry favour with police officers to ‘get business.’”[56]

The fee system was still partially in place when the Mewett Report came on the scene more than a decade later.

However, by the time the Law Reform Commission issued its report, some important changes had been introduced based on the recommendations contained in the McRuer Report:

- In 1968, a training manual was prepared for the justices of the peace by the senior Crown Attorney;

- In 1970, the salaries and working conditions of full-time justices of the peace were established by Order-in-Council – this did not extend to the many part-time justices of the peace in the province (who continued to be paid on a piece-work basis); and

- In 1971, justices of the peace were given additional powers to adjourn cases in the absence of a trial judge.[57]

Calls for Change in the OLRC Report

The Ontario Law Reform Commission reiterated – with distinct urgency – McRuer’s basic call: put the office of the justice of the peace on an established and organized basis. “The exact number of justices of the peace is not known…the relationship of the justices of the peace to the Provincial judges and the Provincial Court system as a whole is a somewhat loose one and in urgent need of clarification.”[58]

In 1973, it appeared to the Law Reform Commission that the number of justices of the peace had risen to slightly over 1,000, and despite McRuer’s calls for a “fresh start,” appointments as a political reward were continuing apace.[59]

Echoing the McRuer Report, the Ontario Law Reform Commission (OLRC) noted that, on the grounds that they were completely inactive, over 500 of those justices of the peace should never have been appointed, or ought not to be continued in office.[60]

The Law Reform Commission made the following findings and recommendations:

- Control: The Commission envisioned a system in which justices of the peace would be appointed to serve in only one county or district and would be supervised and controlled by the local judges of that county or district. Further, “it is anticipated, for example, that one justice of the peace might be assigned to try certain offences while another might be assigned to conduct “show cause” hearings with respect to interim custody and release.”[61] This assignment of particular duties would mean the justice of the peace would then develop expertise in one area.[62] Ultimate supervision and control for the justices of the peace would rest with the Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).

- Appointments and Review of Justices of the Peace: The Commission was critical of the process of appointing existing court staff to be justices of the peace – serving as justices of the peace while they were still holding their civil service appointments. It recommended the establishment of a Justice of the Peace Review Council to both examine proposed appointees and to receive and investigate complaints.

- Fees vs. Salaries: The recommendation was simple – all justices of the peace should be paid on a salary basis.

- Education: The Commission found the training to be “totally inadequate” and recommended that the Chief Judge of the Criminal Division take on responsibility for developing a continuing education program for all justices of the peace. It further was highly critical of the role Crown Attorneys could play in terms of “advising justices of the peace” with respect to offences.[63]

“Baleful Quarters”

In discussing the accommodations for justices of the peace, Alan Mewett said “in no case are they more than adequate and in most cases they remain less than adequate. The reason is that no one has objectively decided precisely what the needs of the Justices of the Peace are. In the first place, whatever is provided, the one location where a Justice of the Peace should not have office facilities is in a police station.”

The media was alert to the impropriety of locating justices of the peace in police stations too. Here is an excerpt from a Globe and Mail editorial entitled “Baleful Quarters” on October 31, 1980:

“We find surroundings so dismal and so inappropriate that Justice of the Peace R.E. Faulkner simply refused to allow the proceedings – bail hearings – to continue. It was not just that the reception area for prisoners at the Don Jail (a room used for delousing and rectal examinations) contributed to the bleakness of the atmosphere; it meant exclusion of members of the public from a process which is supposed to be open. Mr. Faulkner, there for show-cause hearings concerning bail for 16 prisoners arrested the previous night, was quite right to hold out for an open court and for improvements all around.”

The Office of the Justice of the Peace as Mewett Found It in 1981

A couple of significant changes had occurred as a result of the OLRC Report:

- A Justice of the Peace Review Council was established in 1973 – but it did not have the full range of powers the OLRC had recommended. Rather, its functions were limited to reviewing the conduct of justices of the peace and receiving and investigating complaints. The old style of recruiting new appointments – a casual word-of-mouth process, that favoured existing court staff – was still in existence and heartily criticized by Mewett for lack of transparency and little emphasis on actual qualifications of new appointments.[64]

- Justices of the peace were made subject to the general supervision of the Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).

So What Did the Structure of the Office Look Like in the 1980s?

Short answer: confusing! Justices of the peace performed a wide variety of roles in the justice system – but not all did everything. In fact, some were justices of the peace in name alone – they did no work at all, but still held the title.[65]

A common theme from 1968 until 1989 was the lack of complete knowledge about who was doing what. In 1971, it was reported that the number of justices of the peace rose to slightly over 1,000.[66] In 1981, Mewett estimated that approximately 730 people held commissions as justices of the peace – but only about 600 of them were working as justices of the peace, some full-time, some part-time. But this was no more than an educated guess.

In the group of “active” justices of the peace, there were four basic classifications, which were referred to as “directions.” When first appointed, a justice of the peace had absolutely no real powers or duties until “directed” by the Chief Judge of the Criminal Division, the Chief Judge of the Family Division, or a Provincial Court judge designated by either Chief.[67]

There were five categories of directions that conferred power on the justices of the peace: A Expanded, A, B, C and D. A Expanded was the broadest, and D the narrowest. Each category could do everything that the categories below it could do, but could not do anything specified for the categories above it.

The Five Categories of Justice of the Peace

A review of the five categories “directions” provided to justices of the peace reveals the significant difference in powers amongst this bench.

A Expanded: could preside at trials of summary conviction offences under provincial statutes or municipal by-laws, and deal with certain offences under federal legislation;

A: could do everything an A Expanded direction could do, but could not deal with certain offences under federal legislation;

B: could conduct bail hearings;

C: could issue search warrants;

D: could receive informations and issue summons and warrants.

(Source: Mewett Report)

So, how were these directions allocated? Again, Mewett was highly critical of this process.

“The issuing of directions does not always work well. Directions are unfortunately considered by many to be a question of prestige – the A direction justice of the peace being perceived as being higher up the ladder than a D direction justice of the peace. There is an unfortunate tendency to issue A directions quite unnecessarily as a kind of reward when a lower direction would adequately suffice…Similarly, it appears that the local judge does not always seem to recognize that being satisfied that a person is qualified as a justice of the peace is not the same as being satisfied that he should have a particular direction.”[68]

Mewett’s Recommendations

Mewett saw the office of the justice of the peace as essential to the functioning of the justice system in Ontario. He concluded, however, that the “loose” structure of the office – as demonstrated by, for example, the lack of training, the threats to judicial independence, the ad hoc appointment process, and the “fee for service” remuneration system – needed to be rectified.

Many of his recommendations echoed those of the OLRC but he added a key recommendation that would serve to radically change the structure of the office of the justice of the peace.

“It will by now be apparent that I propose an office considerably more structured than at present for the general supervision of Justices of the Peace,”[69] Mewett concluded. He recommended the creation of a position he called “Associate Chief Judge (Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace)” in the Provincial Court. “His duties as I see them would be the assignment and organization of all justices of the peace, including the organization of all training programmes and educational seminars; the circulating of all memoranda, recent decisions and matters of interest to all justices of the peace; the initiation of requests for Directions on all doubtful matters of law or practice; and presiding over the Justices of the Peace Review Council in all its functions as to the appointment proceedings or recommendations as to withholding pay increases or as to long-term disability leave.”[70]

Another landmark recommendation made by Mewett concerned the appointment of native justices of the peace. “Justices of the peace should bear some reasonable correlation to the communities they serve…On any criteria it is impossible to justify the relative total absence of native peoples from the ranks of justices of the peace, save on, namely, that they are not in fact, available.” [71] To rectify this situation, Mewett proposed public education programs and training on reserves about the role of the justice of the peace, with the goal of actively recruiting native candidates to become justices of the peace and to ensure that these candidates had been approved by their communities.[72]

Mewett’s Recommendations Take Flight

When Zuber published his report in 1987, he acknowledged the Mewett Report and the fact that there was little for him to recommend because Mewett’s Report had been so comprehensive – and influential. “There is presently before the legislature an Act to review the Justices of the Peace Act which will, in general terms, implement most of the Mewett recommendations, particularly with respect to the appointment, remuneration and supervision of the justices of the peace.” [73] The legislation Zuber was referring to was the Justices of the Peace Act, 1989.[74] It came into force on August 30, 1990. However, two key initiatives had been acted on prior to this new legislation:

- The development of the Ontario Native Justice of the Peace Program in 1986, and

- The appointment of a Provincial Court judge – Gerald Lapkin – as a “Senior Provincial Judge” in 1988. He would later become the Coordinator of Justices of the Peace in 1990.

Organizing the Office of the Justice of the Peace: The Appointment of a Senior Provincial Judge in 1988

Gerald Lapkin took on the role of Senior Provincial Judge in November 1988 and immediately began organizing the office of the justice of the peace. Justice of the Peace Frank Devine said of Lapkin: “He spent a good deal of time figuring out how many justices of the peace there were in the province. Then he started to put in place a structure to administer them. He also instituted a lot more training for us and that meant we started doing more sophisticated work. A lot more bail hearings, for example, because we’d received training to do them.”

According to Lapkin, part of that administrative structure involved converting justices of the peace from the old fee system into a full-time, salaried bench. “There would be no more fees for services. That had led to many of the problems. The first thing I had to do was to find out how many justices of the peace there actually were. There were no complete records! I found someone in Courts Administration to help me – Anatol Sywak. We started as two people in an office in Old City Hall. We actually found people who were acting as justices of the peace who never had an Order-in-Council from the government! Some justices of the peace never put in for fees. They saw their work as a public service. We tracked other people by payments made to them. It took us over a year to identify what we felt were most of the justices of the peace acting in the province. But even over the next few years, we discovered others. We sent out letters to everyone involved in the legal system, bar, police offices, court offices: tell us of anyone who is a JP. Ultimately we came up with a list – with some 650 names on it.”

This would serve as the groundwork for a process that would begin in earnest in 1994 – the “conversion” of the justices of the peace to a fully “salaried” bench – no more fees.

(Source: Interview of F. Devine for OCJ History Project, 2014 and Interview of G. Lapkin for OCJ History Project, 2014)

“Dear Justice of the Peace”

On May 18, 1989, Senior Provincial Judge, Gerald Lapkin, sent out a letter to all known justices of the peace in the province – asking them for basic information about themselves and their work. Reading the introductory paragraphs of the letter, it’s obvious how little information was known about who served as a justice of the peace in 1989 and what precisely they were doing in that role:

Court Facilities and Accommodations

Funding for the Provincial Courts

Low levels of funding for Provincial Courts had always been an issue – and dramatically affected the accommodations for both judges and justices of the peace. McRuer described them as “probably the most important and most neglected courts in Ontario.” [75]

Chief Judge Andrews graphically described the rag-tag system developed for family courts and which affected the consistency of the courts with respect to staffing levels, court facilities and calibre of judges. He described the situation pre-1968 as depending on whether “…it was a ‘good roads’ municipal council or one with a social conscience.” Further, a great deal depended on the “salesmanship” of the local family court judge – with the result that there was no uniformity in the type and quality of service available.[76]

The 1968 Provincial Courts Act was intended to rectify this situation. One of the major effects of the 1968 Act was to regularize the status of the family courts, and centralize their administration. One important step in that direction was the creation of a Rules Committee to make rules regulating any matters relating to the practice and procedure of the new Provincial Courts (Family Division).[77]

Places of Sitting and Physical Facilities

Lack of funding caused the sometimes dire accommodations for courtrooms across the province. The ability to conduct a fair trial was often placed in question. “Makeshift courtrooms exist in rented parish and legion halls, community centres, service clubs, tavern and lounge areas (complete with a bar located in front of the judge’s dais displaying a sign admonishing patrons to ‘return all glasses’), motel rooms and basements, and in police offices in which the apparent, close and unavoidable contact between the judge and police officers before court does not, in the eyes of the public create an atmosphere of impartiality.” [78] Judges sat in courtrooms like this across the province. In 1971, for example, they sat in 129 different cities, towns and villages – and many judges were itinerant, travelling from town to town.

An Itinerant Court

What did a week look like for the judge of an itinerant court in 1971?

“The situation in the County of Bruce is illustrative of what prevails in southern Ontario, that county being typical of most, it not all, of the counties where the court is itinerant. The court sits in four different localities as follows: in Walkerton every Monday; in Wiarton every Tuesday; in Southampton every Wednesday, and in Kincardine every Thursday. Fridays are set aside in Bruce County for special cases or overflow cases. Thus the judge, who has his office in Walkerton, must travel three times a week to the other three centres, the distance from Walkerton to Kincardine being 25 miles, from Walkerton to Wiarton 63 miles, and from Walkerton to Southampton via Kincardine 63 miles.”

(Source: OLRC, Report on the Administration of Ontario Courts, Part II, 1973, p. 23.)

In 1975, author Sheila Gormley aptly described the experience of appearing in a Provincial Court in Maclean’s Magazine:

“…every day…thousands of people – not just thieves and rounders and bleary-eyed drunks but decent folks just like ourselves and our neighbours – stand before a judge in a bare, functional, usually undersized room and admit guilt or protest innocence. These are the lower courts; in Ontario they used to be called Magistrates’ Courts, and are now (for the purposes of creating a veneer of dignity) the Provincial Courts.

Justice here is no shining abstract, but something to be negotiated, fumbled for, approximated. It’s unfortunate, certainly, that the only confrontation most people will ever have with the majesty of the law will be at this terribly unmajestic level, but as with most things we get what we pay for and the Ontario government is paying as little as possible for the administration of justice. The result is overcrowded courtrooms and dockets, too few judges, confusion and error and sharp tempers and a good many people wondering if they’ve really had their mythical day in court.[79]

By 1989, Gormley’s description was still all too apt. In the 1987 Report of the Provincial Criminal Court Judges Special Committee on Criminal Justice in Ontario (the “Vanek Report), the judges of the Criminal Division, prompted by their concerns about the state of justice in Ontario and their ability to deliver it in the existing conditions, spoke out about the dire courtroom facilities, stating that not much had changed since 1975 in many of their courtrooms.[80]

The northern reaches of the province proved particularly difficult to serve. “There are special problems created [in the north] by the greater distances between court locations and by transportation difficulties, especially during the winter months and the spring break-up.”[81]

The Ottawa Courthouse sits at the corner of Elgin Street and Laurier Avenue. (Photo: Ottawa Citizen)

Our courts were spread all over town,” recalled Justice Paul Bélanger. This was the situation faced by the Provincial Courts in Ottawa during the 1970s and early 1980s before the opening of the Elgin Street Courthouse in 1986.As the Provincial Courts had grown and become busier, courtrooms were found in several locations, including a police station and even a ballroom at a downtown Holiday Inn.

“Because of legislative changes, our jurisdiction had expanded. This meant more cases coming in. As we hit the Charter years, things got more complicated as we began receiving numerous Charter applications and trials grew in length,” explained Bélanger, who was appointed to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in July 1978. Not only were lawyers running all over town for hearings, judges – as they became increasingly professionalized – grew concerned about the perception of holding court in a police station.

The Ottawa Courthouse is home to both the Ontario Court of Justice and the Superior Court of Justice. (Photo: Ottawa Citizen)

The years of “long pleading” for new court facilities began with then Attorney General Roy McMurtry. Bélanger, who prior to his appointment to the bench served as president of the County of Carleton Law Association in 1977, was renowned for his “tenacity of purpose” in making the case with McMurtry for a new courthouse. Problems of security and overcrowding became so dire that the Association threatened to sue the provincial government and, finally, in the fall of 1979, McMurtry announced a new facility would be built to house all levels of court in one structure.

The symbolism of including all courts under one roof was a clear sign of the government’s recognition of the enhanced reputation and importance of the Provincial Courts and a marked departure from the previous practice of housing Provincial Courts in often isolated and substandard premises.

“It was a gradual process,” stated Bélanger, “but there was gradual recognition by everyone in the justice system that courts aren’t meant to accommodate judges but, rather, the people who come to them. A judge is a judge and a courtroom is a courtroom where size and interior configuration should be predicated on function and not court level.”

Bélanger, together with members of the County and High Courts (precursors of the Superior Court), the bar and administration, was an active participant in the “users’ committee” that worked with the architects in the design of the new courthouse. As he remembered, it was a challenging committee to serve on because of the ingrained approach to courthouse construction where vertical location and interior appointments reflected the perceived hierarchical status of individual courts. It is to be noted that Bélanger who served as the region’s senior judge during the years of the courthouse planning and construction, was an influential and successful advocate for the Provincial Court, because the courts and accommodations for both the Provincial and Superior Courts are remarkably similar.

Upon its completion, the Elgin Street Courthouse was the largest courthouse in Canada at 400,000 square feet. Although not all courtrooms were completed on the date the courthouse opened, space was allocated for 35 courtrooms – some of which were meant to be shared by all courts housed in the new building. The equality of the courts was further recognized in a variety of architectural features, including an 85-foot atrium at the centre of the building. “That is a symbolic opening between the levels of courts in Ontario,” stated Bélanger. Another symbolic opening exists in an internal atrium between the fifth and sixth floors of the building, with a broad staircase which links the offices of the judges of the Ontario Court of Justice with those of the Superior Court.

When it opened, critics immediately recognized the new courthouse as “an austere and appropriately respectful temple for the dispensing of Ontarian justice.”

Although they appear real, the stones on the side of the Ottawa Courthouse are works created by the artist collective General Idea.

Upon Bélanger’s retirement from the bench in 2008, tales were told of his integral involvement with the courthouse. “Justice Paul Bélanger has been such a fixture on the bench of the Ontario Court of Justice that a courthouse legend holds that he personally chose the stones that adorn the outside of the building on Elgin Street…The rock story is one myth he is quick to dispel.”

The stones on the side of the courthouse had been an architectural challenge. The province had decided to affix large natural stones that would represent the geology of the Ottawa Valley, recalled Bélanger. During construction, however, the real stones were found to be too heavy to attach safely and they were replaced with fibreglass castings.

“There’s not a real stone in that bunch,” Bélanger said.

(Sources: Colin D. McKinnon, “County of Carleton Law Association, The Brass Ring: 1965-1988,” The First Century: The County of Carleton Law Association, 1888-1988, Bonanza Press Limited, pp. 68-106; Rhys Phillips, “Powerful and somewhat aloof, courthouse still a success,” Ottawa Citizen, December 27, 1986; “Courthouse legend Bélanger flourished in leadership role,” Ottawa Citizen, November 13, 2008, Interview of P. Bélanger for OCJ History Project, 2015.)

Toronto’s Old City Hall – “Organized Confusion”

In 1973, the Ontario Law Reform Commission was highly critical of the situation of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) at Old City Hall, “where the largest number of criminal cases are tried and the greatest number of problems occur.” At that time, an average of between 200 and 300 new criminal charges were received at Old City Hall each day.A number of factors were criticized:

- Not enough personnel, including four judicial vacancies,

- An overworked Chief Judge – which meant an absence of any central administrative co-ordination and control over the scheduling of cases, and

- The inappropriate physical structure at Old City Hall – it was not built as a courthouse, which meant no waiting rooms, no proper facilities for prisoners, who are transferred through public hallways, inadequate courtrooms especially concerning acoustics. “Even under ideal conditions it is difficult for an accused person who is appearing for the first time, often without counsel and highly apprehensive, to understand what is happening.”

The result? “The backlog of cases is enormous. Trials do not proceed, and indeed are often not expected to proceed on the dates for which they are set…there arise the occurrences of delay, haste and confusion, which are a reflection of the low priority given to the administration of justice at Old City Hall.”

(Source: OLRC, Report on the Administration of Ontario Courts, Part II, 1973, pp. 39-41.)

By 1989, the vast majority of both criminal and family matters in Ontario were heard in the Provincial Courts. Nearly 80% of the total family law caseload for the province was dealt with in the Provincial Court (Family Division) and more than 90% of the criminal cases were disposed of in the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).[82]

How did this come about?

Work of the Criminal Courts

The Expanded Criminal Jurisdiction

The Ontario Court of Justice is the de facto criminal trial court for the province. That position was firmly established as a result of changes to the Criminal Code which began in earnest in the 1960s. These changes served to consistently increase the jurisdiction of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) during this period. What did this mean in practical terms? This was a sea change from a Magistrates’ Court handling vagrancy matters to criminal judges hearing the most complex armed robberies and sexual assaults. More complex criminal cases, with more sophisticated legal arguments began coming to the Provincial Court – and the Court began to establish itself as the “specialist” criminal court for the province.

“All of these changes to the Criminal Code both enhanced and expanded our jurisdiction,” recalled Justice Paul Bélanger who was appointed to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in 1978. “These additions were one of the key factors that forced our bench to become more professional.”[83]

What did a trial look like before a judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division)?

It was a simpler time during the 1970s and 1980s, when Brian Lennox was practising as a defence lawyer and Crown Attorney. He described how a provincial criminal court operated in those days and what a trial judge would have heard and seen:“The pace of litigation was rapid, the cases generally short in length…At that time, the practice of criminal law in the Provincial Courts of Canada was almost entirely oral. Prior to 1991, there was no formal requirement of disclosure, which appeared to be entirely within the discretion of the Assistant Crown Attorney. Although such a practice would now likely be considered negligent, it was not unusual for defence counsel to receive disclosure of the Crown’s case for the first time by listening to the Crown’s witnesses testify in chief.Counsel, both Crown and defence, prided themselves on their ability to adjust quickly to new or changing evidence and to argue in consequence.

At a time when the principle ground of admissibility of evidence was relevance, legal argument was limited and most arguments were entirely fact-based. If evidence was relevant and material, it was generally admissible.

The search warrant provisions of the Criminal Code were largely ignored because of the principle of relevance and it was rumoured that, in some jurisdictions outside of Ontario, pre-signed blank search warrants were available to police for the asking.

Pre-trial and trial motions were largely unheard of within the provincial criminal courts and it was a rare counsel who would ever be obliged to put pen to paper in a criminal trial.”

(Source: Lennox, Brian W. “Opportunities for Advocacy in the Ontario Court of Justice,” Remarks to The Advocates’ Society, February 17, 2004).

The Elimination of Trial de Novo

Until the late 1970s, an appeal from either the Criminal or Family Division of the Provincial Court was often heard by way of trial de novo – or “new trial.” In other words, if a decision of a Provincial Court judge was appealed, a federally appointed judge would re-hear the trial all over again. Practically, this meant the original trial before the Provincial Court could be considered a “test run,” with the ability to do it all over again in the appeal to a superior court. Not only was this situation demoralizing for the Provincial Court judges, it was also inefficient. The Criminal Code amendment which eliminated the trial de novo in summary conviction matters came into force in 1977 – and thus increased the importance and weight given to summary conviction trials in the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).[84]

The Creation of Provincial Offences Courts

In 1979, the jurisdiction of the Court was changed so that judges generally no longer dealt with minor summary matters but only the more serious summary conviction matters. [85] The responsibility for minor summary offences – things like not wearing a seatbelt and highway violations like speeding – was transferred to justices of the peace (although judges could still be assigned to cases involving provincial offences – these cases tended to be more serious provincial offences). As Justice Gerald Michel recalled: “In the 1960s, magistrates spent half of their time presiding over highway traffic offences or other provincial regulatory offences. That changed with the enactment of the Provincial Offences Act.”[86] This meant that, just as judges had seen their jurisdiction and workload increase due to changes in the Criminal Code, justices of the peace now took on significantly more work and responsibility. “The justice of the peace bench began to mirror the natural history of the police magistrates, evolving into a more professional bench.”[87]

In the early 1970s, “the criminal justice system was headed for a complete breakdown,” recalled Judge David Vanek.[88] The Courts were clogged with these minor summary offences – which were then tried in the same ways as criminal offences – as more and more of those offences were heading into the Provincial Courts. The crunch was on and the Provincial Offences Act (POA) was designed to streamline and simplify the legal procedures for minor offences.[89]

The POA served as a procedural code for the prosecution of provincial regulatory offences. At the same time, Ontario – notionally – created a new set of “Provincial Courts” called the “Provincial Offences Courts.”[90] The POA provided that either a justice of the peace or a provincial judge could preside in provincial offence proceedings. In practice, justices of the peace began presiding over almost all provincial offences trials. At the same time, the legislation conferred on Provincial Court judges appellate jurisdiction to hear all appeals in these minor summary matters. There is provision for an application to be made to have a provincial judge preside over the trial of more complex provincial offence trials – for example, under the Environmental Protection Act or the Occupational Health and Safety Act.

Controversy! Default Convictions and Set Fines

The Provincial Offences Act was revolutionary when it came into force on March 31, 1980. A key element of simplifying court procedures was the notion of “default conviction.” Simply – if a person ignored a ticket and didn’t respond to it, the Court could assume the person wasn’t disputing the charge and impose a “set fine,” which served as the base fine that could be imposed on the person.“

The idea that you could give someone a ticket and if they didn’t respond they could be convicted was shocking to criminal lawyers.” [91]

Because people needed to know what the financial penalty would be if they didn’t respond, Chief Judge Fred Hayes created a list of “set fines” for each of the hundreds of offences created under provincial laws. “It was a massive task to introduce set fines and Hayes created the system from scratch.”[92] The list of set fines continues to be regularly maintained, updated and publicized by the Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice.

Work of the Family Courts

The period between 1968 and 1989 was a time of significant change in both the structure of the Provincial Court (Family Division) and the work of the family judges.

In 1968, the jurisdiction of the Family Division fell into the following broad categories.

- The conduct of the child – the “juvenile delinquent” as defined by the Juvenile Delinquents Act – and the conduct of their parents as contributors to delinquency; the Court also heard applications to send children to training schools under the Training Schools Act.

- Spousal and child support under the Deserted Wives’ and Children’s Maintenance Act that required the judge to decide who was at fault for the failure of the marriage. Only an “innocent” wife could receive support, and her adultery was a bar to her support claim. This also included the enforcement of support orders made under this legislation or the Divorce Act. The Court could also deal with custody and access as part of a support order.

- Affiliation proceedings to determine paternity and then impose support obligations; a woman required “corroboration” for her testimony to establish paternity.

- Child protection proceedings brought by Children’s Aid Societies.[93]

In essence, there were two family law systems. Superior court judges had, for constitutional reasons, exclusive jurisdiction over divorce and family property and, as part of the divorce proceedings, the superior courts also dealt with support and custody. Family judges in the Provincial Court were doing a large segment of the family law work in the province, but the Court was perceived as the “poor person’s” court, with the real applicant in many support cases being the government body that was providing welfare to the separated or unwed mother. Those with resources and property went to the superior courts.[94]

Even when a matter had begun in the Provincial Court (Family Division), it was sometimes possible to start all over again in the superior courts, if a litigant was unhappy with the result.

By 1989, the Family Division still dealt with the vast majority of family law cases but much had changed.

- Its jurisdiction had broadened to include support and custody proceedings for unmarried couples. Affiliation proceedings no longer existed, as children were treated in the same way whether or not parents were married. Even more important, the fault-based system of family law had been eliminated.

- The Juvenile Delinquents Act had been repealed and replaced by the Young Offenders Act that provided more legal rights for youth, including the right to legal counsel.

- The Court now had exclusive jurisdiction over adoption.

- Child welfare laws had been amended in ways that greatly increased the Court’s authority to hold the children’s services system accountable, for example by determining when a young person could be placed in new secure treatment facilities.

- The right to have a fresh trial (a trial de novo) before the superior courts had been eliminated.

- A well-developed family duty counsel system was put into place.

Two systems of family law still existed, however, and, at least in larger centres, wealthier separating couples and their lawyers usually began proceedings in the superior courts. However, the status and profile of the Provincial Court (Family Division) had changed dramatically. This was, in large measure, due to the calibre of the judges who had joined the Court in the 1970s and 1980s.

The New Family Court Judge

Judge James Karswick was a good example of the judges who joined the Court. His experience illustrates the changing world of family law in the Provincial Division.