The Ontario Court of Justice

Introduction

Transforming the Justice of the Peace System

Establishing Principles of Judicial Office

Criminal Law Developments

Family Law Developments

Becoming a More Integrated Court

New and Modern Ways of Serving the Public

Serving Aboriginal Communities

An Interest in the Court’s History

The Court in 2015

Conclusion

Introduction

A Different Type of Historical Overview

The Ontario Court of Justice History

contains overviews of four time periods.

1867 to 1967

Magistrates’, Juvenile and Family Courts

1968 to 1989

Provincial Courts

1990 to 1999

Ontario Court (Provincial Division)

2000 to 2015

Ontario Court of Justice

The fourth overview (2000 to 2015) is

comprised almost entirely of information

extracted from three reports published by the Court:

- Annual Report 2005

- Biennial Report 2006-2007

- Biennial Report 2008-2009

This information is updated with information contained

in speeches delivered by the Court’s Chief Justices

at Opening of Courts ceremonies during these years.

Through this information, we begin to tell the story of

the Court in the post-millennial era.

“The sheer volume of cases with which the Court deals each year and the large number of people who appear in varying capacities before the Ontario Court of Justice mean that, for many of the citizens of Ontario, the Ontario Court of Justice represents the face of justice within the province.”

Annual Report 2005, Ontario Court of Justice

By 2000, following many years of change – in jurisdiction, structure and organization – the Ontario Court of Justice entered a period of stability. That stability, fostered under an established governance and administrative structure, allowed the Court to continue its growth. This expansion took several forms – the volume and complexity of matters handled and the number of people appearing in the Court, the complement of judges and justices of the peace, and the diversity of backgrounds of those judicial officers, to name a few.

This overview differs from those prepared for the previous three time periods that make up the Ontario Court of Justice History – for two critical reasons.

First, more information documenting the workings of the Court exists from 2000 onwards, than for previous periods. Second, at the time of writing, the period from 2000 to 2015 continues to be part of the Court’s “present,” as opposed to its historical past. The writing of history, it has been said, requires a certain distance exist between events and analyses before a significant assessment can be conducted.[1]Therefore, instead of providing detailed accounts and stories as were prepared for the three previous overviews, this overview highlights events and developments as recorded in the Court’s Annual and Biennial Reports and other documents issued by the Court in recent years.

Reports of the Court’s Activities – Past and Present

Maintaining detailed records of the Court’s activities and initiatives has been one of the by-products functioning under a more established administrative structure. This began in the early 1990s when Chief Judge Sidney Linden began writing and circulating his Chief Judge’s Newsletters and Benchmark, a collection of information about the Court and its judges[2] – both were circulated only within the Court.

In 2006, Chief Justice Brian Lennox introduced an “Annual Report 2005” – a publicly available document designed to serve a broader purpose than previous Court publications. “This Report is intended to be of interest both to those who already know the Court as well as to a broader public who may as yet be unfamiliar with it,” wrote Lennox in the introduction. Chief Justice Annemarie Bonkalo, who succeeded Lennox in 2007, continued the tradition, publishing “Biennial Reports” for 2006-2007 and 2008-2009.

Although printed for distribution, these Reports – as Lennox explained in the 2005 Report – were “intended to be essentially web-based in order to make them as accessible as possible to the largest number of readers.”

In addition to these public Reports, there has long been a tradition in Ontario – modelled on the English tradition, dating from medieval times – of celebrating the “Opening of Courts” each autumn. This public ceremony, at which the Chiefs of the Court of Appeal, Superior Court and Ontario Court of Justice each deliver a speech, presents an opportunity for the Courts to give a public accounting of their operations – to talk about their challenges, their accomplishments and their aspirations. As such, these speeches serve as an annual record of the “story” of the Courts.

Going forward, the Court is planning to replace the Annual and Biennial Reports of the Court’s activities with an internet-based annual update to supplement the information currently provided on the Ontario Court of Justice website.

Reviewing the Court’s Reports – A Story Emerges

On review of the Court’s Annual Report 2005, the Biennial Reports 2006-2007 and 2008-2009 and a collection of Opening of Courts speeches, several trends, initiatives and developments warrant attention in this overview:

- The justice of the peace system was transformed.

- Principles of Judicial Office were established for judges and justices of the peace.

- Policies were developed to meet the growing volume and complexity of criminal and family cases.

- The work of the Criminal and Family Courts became more integrated.

- The Court explored new and more modern ways to serve the public, including Aboriginal communities and unrepresented parties.

- The Court took an interest in its history which it began to formally document for the first time.

Unlike the previous overviews, this one consists almost entirely of content drawn from the Court’s Reports and Opening of Courts speeches to begin to tell a still-emerging and evolving story.

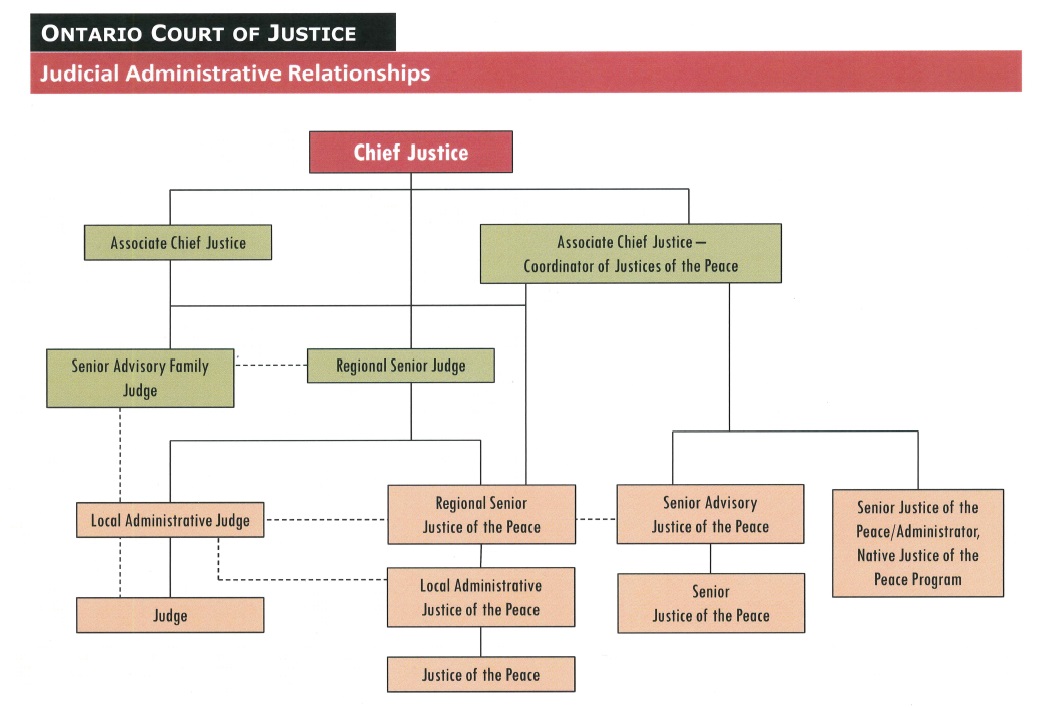

Transforming the Justice of the Peace System

In previous decades, numerous changes were made to transform the system surrounding the judges, including judicial appointments, remuneration, and discipline. Similarly, measures were taken to transform and “professionalize” the justice of the peace system during the early 2000s. The groundwork for this evolution began in the 1990s under the auspices of Associate Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace Marietta Roberts and Co-ordinator of Justices the Peace and Senior Judge Gerald Lapkin. In 2001, when Donald Ebbs’ term of Associate Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace began, he continued to coordinate the transformation.

1999: Establishment of the Justices of the Peace Remuneration Commission

The 1997 decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Reference re Remuneration of Judges of the Provincial Court of Prince Edward Island (the PEI Reference), held that the constitutional requirement of judicial independence meant that provincial governments must create independent remuneration commissions to deal with issues of judicial compensation. As a result of this decision, Ontario’s Justice of the Peace Act was amended in 1999 to require the Lieutenant Governor in Council to establish the “Justices of the Peace Remuneration Commission” consisting of three appointees: one selected by the Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario (which represents the justices of the peace), one selected by the chair of the Management Board of Cabinet, and the chair of the Commission, selected jointly by these two parties. Commencing in 2002, the Commission has conducted an inquiry into the appropriate levels of salaries, pensions, and benefits for justices of the peace every third year. (Note: Since 1992, a Remuneration Commission has made recommendations about judges’ salaries and benefits which are binding on the government.)

2000: Creation of a Professional Association for Justices of the Peace

The Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario is the professional association representing the interests of the justices of the peace of the Ontario Court of Justice. It was formed in 2000 as a result of the merger of the Ontario-wide Justices of the Peace Association and the Justices of the Peace Association of Metropolitan Toronto, which had represented their respective memberships for over 20 years.

2006: Passage of the Access to Justice Act

In the autumn of 2005, the Attorney General of Ontario introduced Bill 14, the Access to Justice Act, 2005 proposing a number of fundamental changes to the justice of the peace system in Ontario, including:

- A move to a completely full-time bench,

- The establishment of formalized qualifications for appointment,

- An independent and objective appointment process,

- A new disciplinary process through the Justices of the Peace Review Council,

- Formal recognition of the office of regional senior justice of the peace,

- The creation of a part-time (per diem) justice of the peace bench – consisting of retired justices of the peace who remain available for assignment.

The Access to Justice Act came into force in October 2006.

A “Significant Reform”

In his Opening of Court speech for 2007, Chief Justice Brian Lennox made the following comments concerning the Access to Justice Act, 2006.

“The passage of the Access to Justice Act, 2006 may well represent the most significant reform of the justice of the peace system in Ontario since 1360, the year in which Edward III enacted a statute entitled What sort of person shall be Justices of the Peace; and what authority shall they have. The Access to Justice Act significantly improves our ability to serve the public and to enhance access to justice of the peace services. “

2006: Phasing Out of Non-presiding Justices of the Peace

Prior to the passage of the Access to Justice Act, justices of the peace were appointed in either a non-presiding or presiding capacity. Some of the duties of a non-presiding justice of the peace included considering search warrants and presiding over bail hearings. A presiding justice of the peace had the same duties but could also be assigned to preside over a trial under the Provincial Offences Act.

The Access to Justice Act amended the Justices of the Peace Act in order to phase out this distinction, so that all newly appointed justices of the peace are appointed as presiding justices of the peace.

2006: Qualifications to Become a Justice of the Peace

Amendments to the Justices of the Peace Act set forth the qualifications to become a justice of the peace. A candidate for the position of justice of the peace must have the minimum requirement of at least 10 years of full-time work experience—either paid or volunteer—and a university degree or college diploma. If the education requirement is not met, an exception can be made if the candidate demonstrates exceptional qualifications, such as relevant life experience.

2006: New Appointment Process for Justices of the Peace

The Justices of the Peace Appointments Advisory Committee (JPAAC) was established by the Access to Justice Act in 2006 to make the appointments process more open and transparent, while including more community and regional input.

The JPAAC advertises annually to seek applications for justice of the peace positions in each region, interviews the candidates and develops the application procedure and the general selection criteria, as well as ensuring this information is made available to the public. Only a candidate whom the JPAAC has classified as “Qualified” or “Highly Qualified” is recommended by the Attorney General to the Lieutenant Governor in Council for appointment. (Note: A Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee, for the appointment of judges, has been in existence since 1988.)

2006: Modification to the Justices of the Peace Review Council

The Access to Justice Act, 2006 made other important amendments to the Justices of the Peace Act, including modifications to the structure, powers, and functioning of the Justices of the Peace Review Council. Effective January 1, 2007, the reconstituted Council deals only with complaints and is no longer involved in the appointments process.

In order to make the Justices of the Peace Review Council’s complaint and discipline process more effective, it was given the power to conduct hearings and make dispositions. This includes the power to recommend removal of a justice of the peace to the Attorney General.

2006: Sitting on a Per Diem Basis

The amendments to the Justices of the Peace Act also allowed retired justices of the peace under the age of 70 years to sit on a per diem (part-time) basis. By the end of 2009, the Ontario Court of Justice had 44 per diem justices of the peace. (As of October 2015, that complement is 345 full-time justices of the peace.) Judges have had a per diem system in place since 1990 and that system is recognized in the Courts of Justice Act. Generally, per diem judges and justices of the peace are assigned in cases of a vacancy or of the illness of a full-time judge or justice of the peace and are also used extensively in dealing with backlog reduction initiatives and special projects.

2008: Change to Retirement Age for Justices of the Peace

As a result of Justice George Strathy’s decision in Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario v. Ontario (Superior Court of Justice)[3], the mandatory retirement age for justices of the peace was raised to 75. In his judgment, released on June 2, 2008, Justice Strathy stated:

Every justice of the peace in Ontario shall be required to retire upon attaining the age of 65 years, but a justice of the peace who has attained retirement age may, subject to the annual approval of the Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice, continue in office until he or she attains the age of 75 years.

This decision applies to all full-time, part-time and per diem justices of the peace. As a result of the decision, six full-time, one part-time and six per diem justices of the peace who had reached the previous mandatory retirement age of 70 years returned to the Court.

On November 28, 2008 the Justices of the Peace Review Council approved criteria to allow for the continuation in office of justices of the peace until age 75. (Note: The mandatory retirement age for judges is also 75.)

2008: Senior Justice of the Peace

The position of Senior Justice of the Peace was created in the Office of the Chief Justice, effective September 1, 2008. The Senior Justice of the Peace advises and assists the Senior Advisory Justice of the Peace and the Associate Chief Justice-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace on all issues pertaining to the education of justices of the peace. The appointment to this position is made by the Chief Justice and has a three-year term which is renewable at his or her discretion.

Three Chief Justices at the Swearing-in Ceremony of

Chief Justice Lise Maisonneuve, May 14, 2015

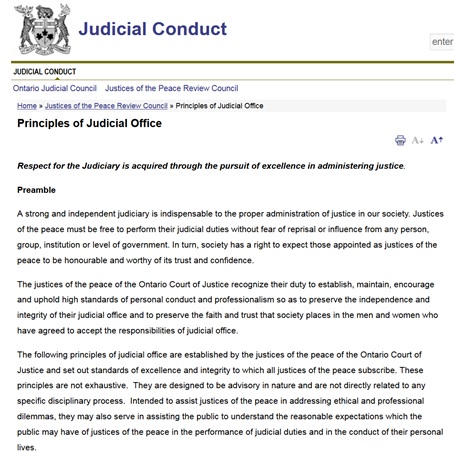

Establishing Principles of Judicial Office

1997: Principles of Judicial Office for Judges

The Courts of Justice Act 1994 authorized the Chief Judge to establish “standards of conduct for provincial judges.” In that context, Chief Judge Sidney B. Linden created a Judicial Conduct Subcommittee which prepared a document entitled Principles of Judicial Office in consultation with the judges’ associations and judges of the Court. The Ontario Judicial Council adopted the Principles of Judicial Office in 1997 as the standard to govern judicial conduct and ethics in Ontario.

2003: Judicial Ethics Advisory Committee

In order to assist judges in dealing with ethical questions, the Ontario Court of Justice created the Judicial Ethics Advisory Committee in 2003 to provide confidential advice to judges and justices of the peace on potential ethical issues.

2005: Ethical Principles for Judges

Among other duties, the Canadian Judicial Council investigates complaints of alleged misconduct involving federally appointed judges. In 1998, it published Ethical Principles for Judges as an ethical frame of reference for the Canadian judiciary.

Upon the recommendation of the Ontario Conference of Judges and of the Chief Justice’s Executive Committee, Ethical Principles for Judges was approved by the Ontario Judicial Council and adopted by the Ontario Court of Justice in early 2005, and now also forms part of the ethical standards for judges of the Ontario Court of Justice.

2007: Principles of Judicial Office for Justices of the Peace

Under the Justices of the Peace Act, the Associate Chief Justice-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace may establish standards of conduct for all justices of the peace in Ontario. This includes the authority to create a plan for bringing those standards into effect once they have been reviewed and approved by the Justices of the Peace Review Council.

In 2007, the Associate Chief Justice-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace initiated the development of judicial standards for justices of the peace. The standards were approved by the Justices of the Peace Review Council in November 2007.

Criminal Law Developments

The following is a collection of developments, highlighting the work of the Ontario Court of Justice in its jurisdiction over criminal matters in Ontario.

Introduction of Specialized Courts

Justice Paul Bentley, standing on the dais in a Drug Treatment Court at Toronto’s Old City Hall. Bentley was a pioneer in the field of problem-solving courts. Here he is shown with Crown Attorney Kofi Barnes (left). Barnes is now a judge of the Ontario Superior Court. Shelley Addley (right) was duty counsel. Bentley died in 2011. (Photo source: Sheldon Gordon, “Falling Through the Cracks,” Canadian Bar Association National, November 2003).

Most courts of the Ontario Court of Justice function in the traditional manner. They focus on arriving at findings after applying the law to the evidence and making decisions in a fair and expeditious manner. A variety of “specialized” courts were created across the province in the 2000s with different orientations or accommodations to suit the needs of particular kinds of cases, accused persons, or witnesses. These specialized courts include:

- Mental Health Courts

- Drug Treatment Courts

- Child-friendly Courts

- Domestic Violence Courts

- Aboriginal Persons (Gladue) Courts

1999: Delay Reduction Initiatives

In 1999, at the suggestion of the Court, a Delay Reduction Committee was created as a backlog-reduction initiative. This Committee included members of the Court and government officials. It worked throughout the 2000s reducing backlog by using short-term additional resources and by making adjustments to the system and identifying court locations that needed more significant and permanent changes.

2008: Launch of Justice on Target

In June 2008, the Ministry of the Attorney General launched the Justice on Target strategy, a province-wide initiative to reduce delay in the Ontario Court of Justice. An Expert Advisory Panel was struck by the government so that justice participants could provide advice in their field of expertise to help the Justice on Target strategy leaders and their team meet the targets. Justice Peter Griffiths, then Associate Chief Justice, was the Court’s member on the panel.

The Justice on Target strategy unfolded at the local level, in individual court locations. Judges and justices of the peace were engaged with other justice sector participants to identify new solutions to the pressing issues of delay.

2012: New Criminal Rules

The new Criminal Rules of the Ontario Court of Justice came into effect on July 1, 2012. The Criminal Rules govern procedures in all criminal proceedings at the Ontario Court of Justice. The previous Criminal Rules were enacted in 1997. In the intervening years, many changes had occurred – in criminal law and practice, court administration, and technology. The new rules are very brief – only five in number – compared to the former 32 rules. Further, the rules are written in plain language with extensive commentary regarding their interpretation and application. This reflects the reality that many accused persons do not have legal counsel or are unrepresented.

The Fundamental Objective of the Criminal Rules of the Ontario Court of Justice

Rule 1 of the Criminal Rules sets out the fundamental objective and describes what is meant by dealing with proceedings “justly and efficiently.”

RULE 1 — GENERAL

Fundamental objective

1.1 (1) The fundamental objective of these rules is to ensure that proceedings in the Ontario Court of Justice are dealt with justly and efficiently.

(2) Dealing with proceedings justly and efficiently includes

(a) dealing with the prosecution and the defence fairly;

(b) recognizing the rights of the accused;

(c) recognizing the interests of witnesses; and

(d) scheduling court time and deciding other matters in ways that take into account

(i) the gravity of the alleged offence,

(ii) the complexity of what is in issue,

(iii) the severity of the consequences for the accused and for others affected, and

(iv) the requirements of other proceedings.

2013: The Ontario Court of Justice Participates in the Cross-Over Youth Project

As part of the Court’s commitment to work with justice partners to help youth avoid a life of high-risk, criminal behaviour, judges and justices of the peace joined the Cross-Over Youth Project that brought together representatives from a variety of sectors involved in youth criminal justice. The project was aimed at reducing the high rate of incarcerated youth in Ontario’s welfare system. In October 2015, a pilot project was launched – in part due to efforts of Justice Brian Scully and Ryerson University professor Judy Finlay – to develop individual and system-wide responses to improve outcomes for these youth.

2015: Launch of Ontario Court of Justice Criminal Justice Modernization Committee

In early 2015, the Court announced a cross-sector committee of senior officials drawn from the Court, the government, the Criminal Lawyers’ Association, Legal Aid Ontario and the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police.

The goal of the Committee is to modernize the Ontario Court of Justice by simplifying Court processes and providing practical operational solutions to better serve the public. It is working to achieve:

- Effective and timely intake and release practices, and meaningful remand appearances,

- Effective pretrial and trial management, and meaningful and timely court appearances, and

- Streamlined and timely processes for in-custody accused, such as better access for defence counsel to in-custody clients and remote appearances.

Family Law Developments

The following is a collection of developments, highlighting the work of the Ontario Court of Justice in its jurisdiction over family matters in Ontario.

2005: A Year of Adjustments in the Court’s Approach to Family Law

In 2005, the Court readjusted its long-term approach to family law. In 1995, the Family Court Branch of the Superior Court of Justice was created – and, at that time, it appeared that this “unified family court” model would expand rapidly through Ontario. This unified family court model had been piloted in Hamilton in 1977.

By 2005, however, it became clear that the pace of expansion would not be as rapid as first thought and that the Ontario Court of Justice would retain its family law jurisdiction in approximately 60% of the province. The Court either shares that jurisdiction concurrently with the Superior Court of Justice or exercises it exclusively in the area of child protection.

To deal with this new reality, the Court reinforced its internal Advisory Committee on Family Law and also created a permanent advisory position of Family Law Counsel within the Court, and began a consultation with the judges of the Court to define a five-year vision for family law work.

2006: Child Protection Backlog Reports

In 2006, the Ministry of the Attorney General and the Ontario Court of Justice jointly established pilot court and community liaison committees at six family court sites in Ontario. The committees’ goal was to identify and address child protection backlog issues and to promote dialogue and issue resolution at the local level. The final reports were submitted to the Ministry of the Attorney General later that year.

The committees were chaired by judges of the Ontario Court of Justice and consisted of local parents’ counsel, Children’s Aid Societies, the Ministry of the Attorney General, the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, the Office of the Children’s Lawyer, Legal Aid Ontario, Crown Attorneys, Aboriginal representatives, and individuals from other community resources.

The sites of the committees were Brantford, Kitchener/Cambridge/Guelph, the Northeast Region (Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury), the Northwest Region (Fort Frances and Kenora), Toronto, and Windsor.

2007: Amendments re Child Protection Assessments

The Assessments Working Group, chaired by a Regional Senior Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice, examined issues associated with assessments in child protection proceedings. The final report of the working group was researched and written by Professor Nick Bala and Dr. Alan Leschied.

The recommendations were presented at the 2006 Justice Summit, and the key short-term recommendations became part of Bill 210, which amended the Child and Family Services Act. The amendments came into force on February 28, 2007.

2007: Family Law Vision Statement

Beginning in 2005, the Court’s internal Advisory Committee on Family Law conducted a round of consultations with the family judges of the Ontario Court of Justice to define a long-term vision for family law. This culminated in a vision statement released by the Chief Justice in July 2007.

2008-2009: Best Practices for Family Programs and Services

The Advisory Committee on Family Law developed Best Practices for the Ontario Court of Justice Family Courts after consulting with family judges as to the services and resources available at each Court. The document recommended that all Courts have a First Appearance Court, Legal Aid Ontario advice and duty counsel, Parent Information Programs, Family Law Information Centres, access to assessments where required, mediators, and designated Family Court staff.

2009: Scheduling Guidelines and Best Practices

In 2009, the Ontario Court of Justice released its Family Court scheduling guidelines and practices. This document was a culmination of work done by the Family Scheduling Guidelines Working Group of the Advisory Committee on Family Law. It sets out guiding principles and best practices when scheduling family matters in the Ontario Court of Justice.

2010: A New Child Protection Training Program for Lawyers

In response to the growing shortage in Ontario of child protection lawyers, Justice Stanley Sherr and the Office of the Chief Justice developed a Child Protection Training Program for lawyers. The first program was held in Toronto in October 2010.

2014: A New Position: Senior Advisory Family Judge

Recognizing the need to support and assist families appearing in the Court, the position of Senior Advisory Family Judge was created. Justice Debra Paulseth was appointed to fill that new position.

Becoming a More Integrated Court

2006: Family and Child Protection Law Education for Criminal Court Judges

To improve its ability to deal with the family caseload, the Court organized the Family Law Primer, an intensive education program on family and child protection law for criminal law judges interested in hearing family law cases.

Held in 2006, the Family Law Primer covered family, child protection, domestic, and enforcement law.

2008-2009: Criminal – Family Intersection Working Group

The Ontario Court of Justice began discussions between judges, Children’s Aid Societies, Crowns, defence lawyers, Legal Aid Ontario, Ministry of the Attorney General personnel, the police, probation and parole officials, and community resources organizations to develop protocols that would assist with the intersection of family and criminal matters.

Subcommittees examined various issues, including order-sharing between the criminal and the family courts and the establishment of an integrated domestic violence court pilot project.

The Court also created a committee to develop better communication between the Criminal and Family Courts for proceedings involving the same family.

2011: Launch of Integrated Domestic Violence Court

Discussions about the potential for an integrated Domestic Violence Court in Toronto started at the Ontario Court of Justice in 2009. A planning team of judges, defence lawyers, Crowns, Legal Aid Ontario, Ministry of the Attorney General personnel, the police, probation and parole officials, Victim Witness Assistance Program personnel, and community resources organizations met to discuss the possible implementation of the pilot Court.

The First Integrated Domestic Violence Court

The Integrated Domestic Violence Court in Toronto, the first of its kind in Canada, was set up in 2011 to resolve the lack of communication between family and criminal courts. It’s an issue that was flagged as a serious problem by the province’s Domestic Violence Death Review Committee in 2004.

(Source: Editorial, Toronto Star, February 2015.)

In June 2011, the Integrated Domestic Violence Court opened its doors at the 311 Jarvis Street courthouse. In this pilot project, a single judge hears both the criminal and family law cases that relate to one family (excluding divorce, family property and child protection matters) where there has been a charge of domestic violence.

|

The Court’s Commitment to Continuing Education “We provide continuing and career-long education to our judiciary. We invest significantly, in time and resources, to regularly updating the curriculum, teaching methods and materials we provide to the judiciary in our more than 50 educational programs held each year. “ These are the words of Chief Justice Annemarie Bonkalo in the 2013 Opening of the Courts speech. The innovative educational programming provided by the Court is often delivered by members of the judiciary. Justice David Paciocco is pictured (left) delivering a presentation to the 2015 Annual General Meeting of the Court’s judges. Pictured below is the assembled group of judges at an educational seminar at the 2014 Annual General Meeting. (Photos courtesy: Antonio Di Zio). |

New and Modern Ways of Serving the Public

In her Opening of Court speech in 2015, Chief Justice Lise Maisonneuve explained that the Court has committed itself to “modernization” and, thus, change. “We have identified, and will continue to identify, innovation and modernization as hallmarks of our judicial leadership.” A few examples of the steps taken since 2000 are enumerated as follows:

2008: Judicial Information Technology Office

In February 2008, the three courts in Ontario established a new information technology organization known as the Judicial Information Technology Office. The office was established to manage and deliver technology services to the judiciary and oversee technology services on the judiciary’s behalf. It is accountable to the executive leads of each of the Offices of the Chief Justice of the three courts in Ontario.

2013: Making Court Statistics Publicly Available

The Court has taken a variety of measures to make information about it more transparent and available to the public.

In April 2013, the Court began posting quarterly Criminal Court data. The Family and Provincial Offences Court data was posted as of July 2013.

In March 2013, the Court issued a “Protocol Regarding the Use of Electronic Communication Devices in Court Proceedings” which permitted electronic recording devices in the courtroom, unless a contrary court order existed in particular case.

In April 2014, the Court introduced a policy regarding access to digital recordings that permitted the media to obtain copies of court recordings without first being required to obtain a court order.

2014: Electronic Orders and Scheduling

In partnership with Court Services Division of the Ministry of the Attorney General, the Court completed the implementation of criminal electronic orders in courtrooms across Ontario. This ensures that the most common criminal orders are available to accused persons, offenders, sureties and justice service providers in simple, plain language.

The justice of the peace bench introduced a new electronic scheduling tool to promote province-wide consistency in scheduling practices. Work began to develop an electronic scheduling tool for the judges.

2014: Posting Court Lists Online

Together with the Court Services Division and the Superior Court of Justice, the Court began to post daily court lists online.

2013-2014: Supporting Unrepresented Litigants

To support the many unrepresented litigants who appear in Criminal, Family and Provincial Offences Courts, the Court published several guides containing basic information aimed at demystifying and explaining Court processes.

The “Guide for Defendants in Provincial Offences Cases,” published on the Ontario Court of Justice website, is one of several guides provided to explain court processes to unrepresented litigants. The “Guide for Defendants in Provincial Offences Cases,” published on the Ontario Court of Justice website, is one of several guides provided to explain court processes to unrepresented litigants. |

Unrepresented Parties

In all cases, the Court strives to ensure that justice is done and that proceedings are fair to both parties. But that task is especially complicated when parties are unrepresented, whether in family or criminal matters. Justice William Horkins of the Ontario Court of Justice describes the challenges in the context of criminal proceedings.

Historically, many judges saw their role as hearing and deciding on the evidence and arguments the parties put before them. Litigants have a fair degree of latitude in deciding what they consider to be relevant and what positions and arguments they want to advance, and it’s usually not the judge’s role to question the choices they make. But when you’re faced with an unrepresented litigant, especially an unrepresented defendant, the court has to take a more interventionist approach.

For example, unrepresented defendants often want to tell their side of the story, and attempt to do so simply by standing up and addressing the court directly. Obviously the judge has to inform them that if they want to give evidence they’ll have to take the stand. But the judge also has to make sure that they’re aware of the possible consequences of that decision: the Crown will cross-examine them, including their character if they choose to put it in issue, and any prior statements they may have made.

It’s a difficult line for a judge to walk. On the one hand, you want to make sure that the defendant understands the proceedings and is making informed choices. At the same time, you have to remain mindful of the fact that you’re there to be a referee—not a coach. In the abstract, the difference between explaining how the system works and giving legal advice seems clear, but it can become much more blurry when you’re confronted with a direct and practical question like “Should I testify?”

Trial judges are always conscious of the dangers of erring too far on one side or the other. No one wants to see a verdict overturned on appeal—either on the basis that you went too far or didn’t go far enough in ensuring that the defendant understood the consequences of what they were doing – and require everyone to go through another trial.

Even in simple cases, dealing with an unrepresented defendant can be time-consuming – and of course, some cases are far from simple. I’ve had trials where we’ve reached the end of the Crown’s case and it has seemed to me that I should at least be considering a directed verdict. If I think there’s an issue of that magnitude, I’ll encourage the defendant to go visit duty counsel and get at least summary advice.

Justice Horkins has developed a checklist for judges and justices of the peace dealing with unrepresented accused, as well as a more comprehensive judicial education program.

There’s a real thirst for guidance in this area. This Court is highly attuned to the need to respond fairly and effectively to unrepresented defendants, and judges are eager to develop their skills and resources.

(Note: A “directed verdict” is a decision by the judge to dismiss a case before the defence has called any evidence because the Crown has not made out the essential elements of the offence.)

(Source: Interview with W. Horkins for OCJ History Project, 2015.)

Serving Aboriginal Communities

2001: Gladue (Aboriginal Persons) Court Created in Toronto

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada, in the decision R. v. Gladue, established criteria for the application of paragraph 718.2(e) of the Criminal Code in the sentencing of Aboriginal offenders. The Court recognized and underlined the need for sensitivity to the particular needs of Canada’s Aboriginal communities within the court system. It recognized that courts and Aboriginal communities must work to design and administer a judicial process with courts equipped to apply the Gladue guidelines.

In 2001, a Gladue Court was established in Toronto at the Old City Hall courthouse. [At the time there were] over 25,000 First Nations persons living in the City of Toronto. The Court was established as a result of discussions between the judges of the Ontario Court of Justice and the Legal Aid Clinic for Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto. The Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto employed three Gladue caseworkers, to write reports on the life circumstances of Aboriginal offenders at the request of defence counsel, the Crown Attorney, or the judge.

These reports (known as Gladue reports) contain recommendations that the Court may consider in sentencing and can be prepared for Aboriginal offenders in any Court in Toronto, as well as for Aboriginal offenders in other regions.

The Gladue Court takes into account the particular circumstances of Aboriginal offenders and takes a restorative approach to sentencing in the event of conviction.

The seven regions of the Court. (Source: Ontario Court of Justice). The seven regions of the Court. (Source: Ontario Court of Justice). |

(Note: Since 2001, a variety of Gladue Courts have opened in regions across Ontario.)

2014: Implementing Recommendations of the “Fly-in Court Working Group”

The Court has long had judges fly into remote communities to conduct criminal and family proceedings. As reported in 2013, the Court co-chaired a Fly-in Court Working Group to identify practical ways to improve justice services in the Far North. Many of the Working Group’s recommendations were implemented in 2014. For example, the Court began scheduling more dedicated Youth Court days in Pikangikum and dedicated one judge to hear family and child protection cases during the Court’s Attawapiskat sittings.

An Interest in the Court’s History

Recording the Story of the Court

In 2005, the Ontario Court of Justice issued its first Annual Report. One feature of the report was “A Selective History of the Ontario Court of Justice.” This marked a growing interest in recording the Court’s history which had, until then, largely remained undocumented.

That first history was prepared under the leadership of Chief Justice Brian Lennox. His successor, Chief Justice Annemarie Bonkalo, expanded on the concept by commissioning a team of authors to create Ontario Court of Justice: A History (“OCJ History”).

That first history was prepared under the leadership of Chief Justice Brian Lennox. His successor, Chief Justice Annemarie Bonkalo, expanded on the concept by commissioning a team of authors to create Ontario Court of Justice: A History (“OCJ History”).

The OCJ History, completed in 2015, presents the Court’s history in an online format through a series of essays, overviews of four time periods, descriptions of major changes, and selected profiles, stories and notable cases.

Historical Exhibit in Windsor Courthouse

Over a 12-year period, Justice Douglas Phillips created a permanent historical exhibit for the Windsor courthouse. He has amassed a display of newspaper articles, judicial photos and other historical items relating not just to the Ontario Court of Justice but to all levels of Court.

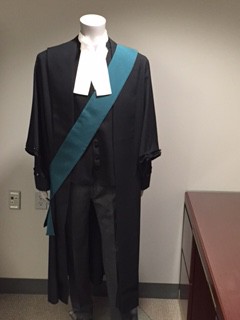

Mannequin wearing justice of the peace gown from historical exhibit in the Windsor courthouse, 2015. (Courtesy: D. Phillips)

The final phase of his work is a display of robes worn by lawyers and members of the judiciary in Ontario over the past 75 years. The robes are fitted to mannequins by a seamstress and each set of robes must be fitted with long underwear (per Smithsonian Institution standards) to prevent damage to the historical fabric caused by the polyurethane mannequins.

As of 2015, Justice Phillips’ goal is to have a floor-to-ceiling temperature and humidity-controlled glass case constructed at the Windsor courthouse to display 12 mannequins, along with the 41 wooden cabinets and 430 historical items already displayed.

Justice Phillips was aided in his work by colleagues from the Ontario Court of Justice, including Justice Gregory Campbell and Justice of the Peace Susan Whelan.

(Source: Adapted from D. Phillips, “Preserving Our Past, With Your Help”, published in “Benchmark,” the internal newsletter of the Ontario Court of Justice).

The Court in 2015

A New Chief Justice: Lise Maisonneuve

I learned – coming from a small town in Ontario’s north – that this is a large, diverse province, with many distinct regions and voices, facing many different issues and challenges. And yet, we are one Court, in one province – striving to provide fair, open and modern justice to all.

Lise Maisonneuve, on being sworn in as Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice, May 14, 2015.

When Lise Maisonneuve was sworn in as the Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice, she represented two “firsts.” She was the first francophone Chief Justice and the first from northern Ontario, having grown up in Timmins. Prior to becoming Chief Justice in 2015, Maisonneuve served as the Regional Senior Justice of the East Region and then as Associate Chief Justice.

| Swearing in of Lise Maisonneuve as Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice, May 14, 2015 |

Associate Chief Justices

The Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice is supported by two Associate Chief Justices. As of 2015, these positions were filled by Faith M. Finnestad (whose role includes serving as Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace) and Peter DeFreitas. Like Chief Justice Maisonneuve, DeFreitas was sworn into his leadership position in 2015.

Swearing in of Peter DeFreitas as Associate Chief Justice, June 24, 2015

Front row: Justice Mary Teresa Devlin; Justice Donald Dodds (retired); Associate Chief Justice Peter DeFreitas; Regional Senior Justice of the Peace Linda J. Kay; Justice Ferhan Javed. Second row: Justice David Stone, Justice Esther Rosenberg; Justice Michael Block; Justice Joseph De Filippis. Third Row: Justice Graham Wakefield; Justice Ronald Richards; Justice of the Peace Allison Forestall; Justice Katrina Mulligan; Justice of the Peace Dolly V. Mecoy; Justice Gregory Regis; Justice John Adamson. (Courtesy: Ontario Court of Justice)

Conclusion

In one sense, the modern history of the Court is better documented than previous periods, in part due to the Court’s relatively recent practice of publishing Annual and Biennial Reports. However, at the time of writing the OCJ History, the events of the previous 15 years (2000 – 2015) were so recent that it would be difficult to analyse their impact and significance. Future historians can look back upon them with the benefit of in-depth research and the perspective afforded by the passage of time.

| Judges | Justices of the peace | ||

| Full-time | per diem | Full-time | per diem |

| Adams, Peter Ralph | Anderson, Charles D. | Agnew, Wendy | Akkanen, John A. |

| Adamson, John F. | Atwood, Hugh K. | Aharan, Peter | Avery, Lawrence W. J. |

| Agro, P.H. Marjoh | Beaman, Judith C. | Aleong, Sonia | Babcock, Elaine |

| Alder, Ann | Bélanger, Paul R. | Allison, Carol Ann | Baldelli, Ivana |

| Allen, J. Elliott | Bellefontaine, Paul L. | Altobello, Gerry | Bannon, Gene A. |

| Armstrong, Simon C. | Bennett, Norman | Amenta, Angelo | Beck, Ronald |

| Austin, Deborah J. | Bonkalo, Annemarie E. | Anand, Jeannie | Begley, Donald L. |

| Bacchus, Sandra | Bradley, William W. | Anderson, Charles | Benn-Ireland, Tessa |

| Baig, Dianne Pettit | Carr, David G. | Anstey, Sandra | Bonas, Prior N. |

| Baker, Kathleen | Casey, Jeff | Avrich-Skapinker, Mindy B. | Boon, Kerry |

| Baldwin, Lesley M. | Cavion, Bruno | Baas, Edith | Boyuk, Dolores M. |

| Band, Patrice F. | Chester, Lorne E. | Baker, Mitchell H. | Brown, Leslie |

| Beatty, George | Cooper, Donald S. | Ballam, Dianne J. | Bruinewood, Jacob W. |

| Beninger, Robert | Cowan, Ian B. | Barnes, Michael | Burgess, Neil |

| Bhabha, Feroza | Crawford, James C. | Baum, Karen | Campbell, Charles R. |

| Bigelow, Robert G. | DeMarco, Guy F. | Beck, Ruby Y. A. | Carmichael, Veronica |

| Bishop, Peter T. | Ebbs, Donald A. | Billich, Samuel W. | Carroll, Jack |

| Blacklock, W. James | Fairgrieve, David A. | Bisson, Richard E. | Casey, Wendy |

| Block, Michael | Forsyth, Frederick L. | Blauveldt, Anna | Chandhoke, Inderpaul S. |

| Bloomenfeld, Miriam | Fournier, Robert N. | Blier, Jean-Marie | Chaput, Gordon |

| Blouin, Richard | Frazer, Bruce J. | Bourbonnais, Sylvie-Émanuelle | De Jong, Jeannette |

| Bode, Marc | Griffiths, Peter D. | Boychyn, Robert G. | Deacon, Patrick |

| Boivin, Ronald Dennis Joseph | Hackett, Donna G. | Brecher, Paulina | Devellano, Linda |

| Bondy, Sharman S. | Halikowski, Donald J. | Bremner, Melanie | Devine, Frank |

| Borenstein, Howard Joseph A. | Hogg, Derek T. | Brihmi, Mohammed | Faulkner, Ralph |

| Borghesan, Pamela | Hryn, Peter | Brown, Hugh J. | Fayolle, Leon |

| Botham, Louise | Hunter, R.G.E. | Bryant, Kathleen M. | Fletcher, C. Jill |

| Boucher, Patrick | Katarynych, Heather L. | Bubba, James V. N. | Forster, Bridget I. |

| Bourgeois, Julie | Kerrigan Brownridge, Jane | Bubrin, Vladimir | Gay, Robert T. |

| Bourque, Peter Nicholas | Kirkland, D. Kent | Buchanan, Donald W. | Guindon, Luc |

| Bovard, Joseph W. | Kukurin, John | Budaci, Stephen | Haddad, Suzanne |

| Brewer, Carol Anne R. | Kunnas, Gary R. | Burton, Samantha | Hepburn, Wilmer |

| Brophy, George J. | Lacavera, Alphonse T. | Camposano, Felicitas | Hilton, Susan |

| Brown, Beverly A. | Lebel, Jean-Gilles | Caron, Bernard | Holmes, Claudette L. |

| Brown, Stephen D. | Lennox, Brian W. | Cassano, Helena | Hudson, Brian |

| Brownstone, Harvey P. | Lenz, Kenneth G. | Chahbar, Abdul | Hudson, Maurice G. |

| Brunet, Jonathan | Lévesque, J.F. Réginald | Chang Alloy, Vernon A. | Hunter, Liette |

| Budzinski, Lloyd M. | Livingstone, Deborah K. | Chapelle, Deanne | Jackson, Diane L. |

| Buttazzoni, Andrew | MacKenzie, Robert S.G. | Charyna, Holly | Jadis, Carole |

| Caldwell, Kathleen J. | Mahaffy, Guy | Chernish, Carol | Jensen, Karen |

| Cameron, Lisa M. | Main, Robert P. | Chiang, Jack | Jewitt, Teresa |

| Campbell, Gregory A. | March, Stephen A.J. | Child, Arthur (Jim) | Kivell, Richard |

| Campling, Frederic M. | Marshall, Lauren E. | Churley, Marilyn | Le Sarge, Richard M. |

| Carr, Ralph E.W. | Masse, Rommel G. | Clare, James H. | Lecouteur, Gilles |

| Caspers, Jane E. | McGowan, Kathleen E. | Clark, Andrew C. | Levitt, Janice |

| Chaffe, James R. | McGrath, Edward J. | Clark, Douglas W. | Lewin, Robert H. |

| Chapin, Leslie | Morgan, J. Rhys | Clysdale-Cornell, Pat | Lippingwell, David R. |

| Chisvin, Howard I. | Morrison, Wayne D. | Conacher, Mark | Logan, Tom |

| Clark, Steven R. | Nevins, James P. | Coopersmith, Maxine | MacDonald, Dan M. |

| Clay, Philip | Omatsu, Maryka | Costa, Ana | McHenry, Patricia E. |

| Cleary, Thomas P. | Ormston, Edward F. | Cotter, Ralph | McKechnie, Clayton |

| Cleghorn, Sarah | Palmer, Gary V. | Cottrell, John R.J. | Miller, Kathleen A. |

| Clements, S. Ford | Pockele, Gregory A. | Coulas, Claudette | Moran, Barry J. |

| Cohen, Marion L. | Regis, Gregory | Crawford, Lena | Mulloy, Norman W. |

| Cole, David P. | Reinhardt, Paul H. | Creelman, John E. | Napier, Alice |

| Colvin, J.A. Tory | Roberts, Marietta L.D. | Cremisio, Angelo | Oates, James E. |

| Condon, John Paul | Stone, David M. | Cruz, Lurdes | Obokata, Leonard |

| Cooper, Alan D. | Taylor, Paul M. | Cureatz, Sam L. | Pallett, Laurie K. |

| Copeland, Jill M. | Thibideau, Lawrence P. | Currie, Donald | Pasch, Terry |

| Crewe, Frank | Wake, J. David | Curtis, Mark | Quinn, Marielle |

| Culver, Timothy A. | Waugh, John D.G. | Cuthbertson, Michael A. | Read, Duncan |

| Currie, Paul R. | Webster, A. Ross | D’Ignazio, Daniele | Redmond, L. Jerome |

| Curtis, Carole | Weseloh, Robert T. | Danbrook, William S. | Rodney, Avis M. |

| Dawson, Nancy A. | Wolder, Theo | Daniel, Esther | Ross, William S. |

| De Filippis, Joseph A. | Woolcott, Margaret F. | De Gannes, Martha | Rozon, Louise E. |

| Dean, Lloyd C. | Zuraw, Anton | Debacker, Holly R. | Saab, Lorraine P. |

| DeFreitas, Peter | Debartolo, Ermelinda | Sculthorpe, Richard C. P. | |

| Deluzio, Elaine | Dechert, Kenneth W. | Squires, Frank | |

| Devlin, Mary Teresa E. | Desjardins, Jacques | Stafford, David S. | |

| Di Zio, Antonio | Di Lorenzo, Dan | Stanghetta, Philip M. | |

| DiGiuseppe, Dino | Diaz, Kristine | Stevely, Donald M. | |

| Dobney, S. Gail | Doelman, Donna I. | Stewart, William H. | |

| Doorly, Kate | Dombrowsky, Leona | Straughan, Carollyn | |

| Dorval, Célynne S. | Donio, Marcel | Tatangelo, Lorenzo | |

| Douglas, Jon-Jo A. | Doran, John | Turtle, William G. | |

| Douglas, Norman S. | Dresher, Karin | Walton, Anthony | |

| Downes, Philip | Dube, Chantal J. | Whalen, Ronald | |

| Duncan, Bruce W. | Dudani, Shailesh | Wiley, Jack | |

| Dunn, Melanie D. | Dudar, Donald | Woodworth, Sharon M. | |

| Dunn, Patrick W. | Duggal, Mangesh | ||

| Dwyer, Nyron | Edwards, Clement | ||

| Edward, Gethin B. | Emrich, Cheri | ||

| Elder, Joyce | Europa, Delano V. | ||

| Epstein, Michael J. | Eustaquio-Syme, Milagros | ||

| Evans, John D.D. | Evans, Susan D. | ||

| Favret, Lucia Piera | Fallon, Sally A. | ||

| Feldman, Lawrence T. | Fantino, Gregory | ||

| Felix, Marquis S.V. | Farnand, Marsha | ||

| Finnestad, Faith M. | Farnum, John B. | ||

| Fraser, Hugh L. | Fatsis, Vasilio | ||

| French, Paul | Fisher-Grant, Veruschka | ||

| Fuerth, Stephen J. | Florence, Darlene | ||

| Gage, George S. | Forestall, T. Allison | ||

| Gee, Robert | Forfar, Ann C. | ||

| George, Jonathon | Forgues, Ginette | ||

| Ghosh, Amit | Forrest, Grainne M. K. | ||

| Giamberardino, Franco | Foulds, Tom L. | ||

| Gibson, David | Frederick, H. Jane | ||

| Glaude, G. Normand | Frederiksen, Michael | ||

| Glenn, Lucy C. | Froese, Thomas Pl | ||

| Gorewich, William A. | Gale, Helen M. | ||

| Graham, M. Edward | Gettlich, Peter M. | ||

| Graydon, Robert | Gibbon, Anna | ||

| Green, Melvyn | Gilani, Maimun | ||

| Greene, Mara | Girault, Louisette | ||

| Gregson, Nathalie | Giulietti, Rosanne | ||

| Griffin, Geoffrey James | Glassford, Thomas | ||

| Grossman, Jack M. | Glover, Joni E. | ||

| Guay, André L. | Greene Summers, Audrey | ||

| Hall, Aston J. | Grewal, Ajit (Jiti) | ||

| Hardman, Paddy A. | Griffith, George | ||

| Harpur, C. Michael | Gunness, Alston | ||

| Harris, C. Roland | Guthrie, John | ||

| Harris, David | Hampson, Anna | ||

| Harris, Peter A.J. | Hartt, Constance | ||

| Harrison, Steven P. | Hawtin, Jane | ||

| Hawke, Kathryn L. | Hayden, Darlene | ||

| Hearn, Gary F. | Hefkey, A. Lis | ||

| Hoffman, Mitchell S. | Henderson, Catherine | ||

| Hogan, Mary L. | Hickling, Catharine E. | ||

| Horkins, William B. | Hiscox, Peter J.A. | ||

| Hornblower, G. Mark | Hodgins, Patricia | ||

| Hoshizaki, Jennifer Ruth | Hodgins, Theodore A. | ||

| Humphrey, Richard A. | Hoffman, Susan | ||

| Hunter, Stephen J. | Hong, Jay | ||

| Javed, Ferhan | Hoppe, Daisy | ||

| Jennis, Richard E. | Hudson, Sylvia | ||

| Johnston, Cynthia | Humeniuk, Carolyn | ||

| Jones, Carolyn J. | Hundal, Bobby | ||

| Jones, Penny J. | Hunt, David J. | ||

| Kastner, Nancy S. | Hurst, Calvin V. | ||

| Keaney, James J. | Hurst, Michael | ||

| Keast, John D. | Huston, Debra | ||

| Kehoe, Catherine Ann | Jafar, Salma | ||

| Kelly, Edward | John, G. Sunit | ||

| Kelly, Robert | Johnson, Ann | ||

| Kenkel, Joseph F. | Johnson, Kathy-Lou | ||

| Khawly, Ramez | Johnston, Alfred (Budd) | ||

| Khemani, Sonia | Johnston, Ronald J. | ||

| Klein, Lawrence | Jolicoeur, Michel F. | ||

| Knazan, Brent | Kay, Linda J. | ||

| Knott, Richard T. | Keilty, David R. | ||

| Konyer, Stuart | Kelly, Brett | ||

| Kowalyshyn, Paul J.S. | Kerbel, Ruth | ||

| Kozloff, Neil | Khan, Rizwan | ||

| Krelove, Glenn D. | Kirke, Leslie | ||

| Kwolek, Romuald F. | Kitlar, Michael G. | ||

| Lahaie, Diane | Konstantinidis, Paula | ||

| Lalande, Randall W. | Kowarsky, Paul H. | ||

| Lambert, Martin P. | Kreling, Herbert H. | ||

| Lapkin, Gerald S. | La Caprara, Dan | ||

| LeDressay, Richard J. | Lafleur, Diane | ||

| Legault, Jean | Lall, Esme | ||

| LeRoy, Jeanine | Lancaster, Stephen | ||

| Letourneau, Allan Gary | Langlois, Paul | ||

| Libman, Rick N. | Lau, Grace P. K. | ||

| Lipson, Timothy R. | Lauzon, Julie | ||

| Lische, Karen L. | Lavallee, Patricia | ||

| Loignon, Jacqueline | Le Blanc, Roger J. | ||

| Lynch, John T. | Leaman, Bruce I. | ||

| MacLean, Susan C. | Leblanc, Linda | ||

| Maclure, Allan S. | Leclerc, Pierre O. | ||

| MacPhee, Bruce E. | Lee, Denis | ||

| Maille, Gilbert R. | Legate Exon, Ruth | ||

| Maisonneuve, Lise | Legault, Serge | ||

| Malcolm, Wendy | Lewis, Mathilda | ||

| Maresca, June | Logue, Louise | ||

| Marin, Sally E. | Longe, Cledwyn | ||

| Marion, Ronald A. | MacDonald, John | ||

| Martin, Eileen | MacEachern, Lauchlin J. | ||

| Mathias McDonald, Catherine | Mackey, Brian | ||

| Maund, Douglas B. | MacKinnon, Danalyn | ||

| McArthur, Heather | Macphail, Paul | ||

| McFadyen, Anne E.E. | Madigan, Kevin V. | ||

| McHugh, Kevin G. | Magoulas, Adriana | ||

| McKay, A. Thomas | Malik, Abdul | ||

| McKerlie, Kathryn L. | Malik, Asad | ||

| McLeod, Donald | Mankovsky, Sheine | ||

| McLeod, Katherine L. | Manno, D. Gerald | ||

| McLeod, Malcolm | Marchand, Basile V. | ||

| Meijers, Enno | Mariasine, Jason | ||

| Merenda, Salvatore | Marquette, Andrew C. | ||

| Minard, Ronald A. | Marum, Patrick | ||

| Misener, Mary E. | McAleer, Diane M. | ||

| Mocha, Cathy | McCraw, Roger Jr. | ||

| Monahan, Paul F. | McIlwain, Constance | ||

| Moore, John C. | McKeogh, Thomas | ||

| Moore, Kimberly | McLeod, Margot | ||

| Morneau, Julia A. | McMahon, F. Michael | ||

| Mulligan, Katrina | McMahon, Gary W. | ||

| Murray, Ellen B. | McMahon, J. Gary | ||

| Nadel, Joseph | McNally, Robert H. | ||

| Nadelle, Jack D. | Mechefske, Monique | ||

| Nakatsuru, Shaun Shungi | Mecoy, Dolly V. | ||

| Neill, K. Stacy | Mews, Cornelia | ||

| Nelson, C. Ann | Mills, Lina M. | ||

| Newton, Petra E. | Miskokomon, Marsha L. | ||

| Nicklas, Sharon M. | Mitchell, Nancy | ||

| O’Brien, Larry B. | Moffatt, Jane | ||

| O’Connell, Sheilagh | Mora, Felix | ||

| O’Dea, Michael P. | Moreau, Michel J. | ||

| ODonnell, Fergus | Morin, Karine | ||

| Oleskiw, Diane | Morris, Jill | ||

| Otter, Russell J. | Moses, Moira M. | ||

| Paciocco, David | Muraca, Luigi J. | ||

| Parent, Lise S. | Murphy, Karen | ||

| Parry, Craig A. | Mutuma, Chimbo | ||

| Paulseth, Debra A. W. | Neilson, Elizabeth M. | ||

| Pawagi, Manjusha | Nelson, Deborah | ||

| Payne, John A. | Nestico, Sam | ||

| Pelletier, Joyce L. | Ng, Sunny | ||

| Perkins-McVey, Heather | Nichols, Paula J. | ||

| Perron, Alain H. | Norton, Brian O. | ||

| Phillips, Douglas W. | Opalinski, Joanna T. | ||

| Pringle, Leslie C. | Parsons, Ernie | ||

| Pugsley, Bruce E. | Peace, Glen | ||

| Rabley, Wayne G. | Pearson, Linda | ||

| Radley-Walters, S. Grant | Peltzer, Christopher | ||

| Rawlins, Micheline A. | Phillipps, Lloyd | ||

| Ray, Sheila | Phillips, Bruce I. | ||

| Ready, Elinore A. | Pilon, Francois J. | ||

| Renaud, Gilles | Premji, Karim | ||

| Richards, Ronald J. | Prestage, Ronald | ||

| Ritchie, John M. | Puusaari, Anne-Marie | ||

| Robertson, Paul | Quamina, Odida T. | ||

| Rocheleau, Michelle | Quinn, Clifford (Barry) | ||

| Rodgers, Gregory P. | Quon, Richard | ||

| Rogers, Lynda J. | Radtke, Herbert H. | ||

| Rogerson, Robert W. | Radulovic, Zeljana | ||

| Rose, David S. | Ralph, Warren G. | ||

| Rosenberg, Esther | Renaud, Angela | ||

| Ross, Lynda S. | Rerup, Renee | ||

| Rutherford, Rebecca | Ritchie, Liisa | ||

| Sager, Melanie | Roberson, Sharon B. | ||

| Schnall, Eleanor M. | Robinson, Donovan | ||

| Schneider, Richard | Roffey, Rhonda | ||

| Schreck, P. Andras | Rogers, Malcolm S. W. | ||

| Schwarzl, Richard | Rogers-Bain, Nancy | ||

| Scully, Brian M. | Rohan, Noel R. | ||

| Selkirk, Robert | Rojek, Walter W. | ||

| Serré, Louise | Romagnoli, Adele | ||

| Shamai, S. Rebecca | Rosenfield, Joseph | ||

| Shandler, Riun | Ross, Lillian D. | ||

| Sherr, Stanley B. | Ross, Norman E. | ||

| Sherwood, Kevin | Ross Hendriks, Mary | ||

| Skowronski, John S. | Rotondi, Santina (Tina) | ||

| Sopinka, Melanie A. | Ryan, Gerald | ||

| Sparrow, Geraldine N. | Ryan-Brode, Maureen | ||

| Spence, Robert J. | Santos, Cristina | ||

| Speyer, Maria | Scarlett, Deborah | ||

| Starr, Victoria | Scarpato, Raffaella | ||

| Stribopoulos, James | Scully, Lauren | ||

| Sullivan, William J. | Seglins, Carol | ||

| Takach, John D. | Seguin, Monique | ||

| Tetley, Peter | Seneshen, Robert | ||

| Tobin, Barry M. | Shelley, Mary | ||

| Tuck-Jackson, Andrea Edna E. | Shoniker, Catherine | ||

| Vaillancourt, Charles H. | Shortell, Robert D. | ||

| Valente, Frank | Shortt, Jamie | ||

| Villeneuve, Robert P. | Shousterman, Rhonda | ||

| Vyse, D. Terry | Smythe, Marie-Christine | ||

| Wadden, Robert | Solomon, Philip (Phil) | ||

| Wakefield, Graham | Solursh, Gerald | ||

| Watson, Ann Jane | Souliere, Beverly | ||

| Weagant, Brian | Spence, Alex | ||

| Webber, Matthew C. | Steenson, Terence | ||

| Weinper, Fern M. | Stethem, Lynette A. | ||

| West, Peter Caldwell | Stewart, G. Susan | ||

| Westman, Colin R. | Stiff, Janice | ||

| Whetung, Timothy C. | Stinson, Thomas | ||

| Wilkie, Peter H. | Swords, Bernard | ||

| Wilson, Joseph B. | Symons, Allan | ||

| Wilson, N. Jane | Tahiri, Najib | ||

| Wolski, William R. | Taylor, Stewart A. | ||

| Wong, Gerri Lynn | Tennant, Patricia D. | ||

| Wong, Mavin | Then, Milan | ||

| Wright, J. Peter | Thompson, Michele | ||

| Wright, Peter Jeffrey | Tivey, Lynn E. | ||

| Young, Bruce J. | Toulouse, Lori-Ann | ||

| Zabel, Bernd E. | Triantafilopoulos, Chris | ||

| Zisman, Roselyn | Valentine, Karen | ||

| Zivolak, Martha B. | Valeriano, Patrice | ||

| Zuker, Marvin A. | Vaughan, Jan M. | ||

| Visser, Kelly | |||

| Vu, Latly | |||

| Waisberg, Stephen L. | |||

| Walker, Eileen | |||

| Walker, Karen R. | |||

| Walton, Bonnie C. | |||

| Wassenaar, Tina | |||

| Watson, Lorraine A. | |||

| Waugh, Barbara J. | |||

| Weiss, Hilda | |||

| Welsh, Paul A. | |||

| Whelan, Susan | |||

| White, Dennis D. | |||

| Williams, Mary Jane | |||

| Wilson, Dennis A. | |||

| Wilson, Peter W. | |||

| Winchester, Claire | |||

| Woldemichael, Sisay | |||

| Woloschuk, Jerry S. | |||

| Wong, Ruby | |||

| Worku, Habte | |||

| Woron, Catherine G. | |||

| Yamanaka, Ronald M. (Ron) | |||

| Young, J. Carl | |||

| Ziegler, James J. | |||

| Zito, Roberto | |||

| Zuliani, Raymond | |||

- Matt Elton, “When does history end?”, BBC History Magazine, October 2009. In this article, the author quotes Professor Paul Fouracre, University of Manchester and that quote is paraphrased here.↩

- In 2011, Benchmark was expanded to include information about justices of the peace.↩

- Association of Justices of the Peace of Ontario v. Ontario (Attorney General) [2008] O.J. No. 2131( Superior Court of Justice).↩