Provincial Court (Civil Division), 1980-1990

The Demise of the Trial De Novo

Simple Justice: The Introduction of the Provincial Offences Act

Moving Bail Hearings from Jails and Police Stations to Courthouses

The Introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Introduction of Legal Aid

Expansion of the Provincial Courts' Criminal Law Jurisdiction

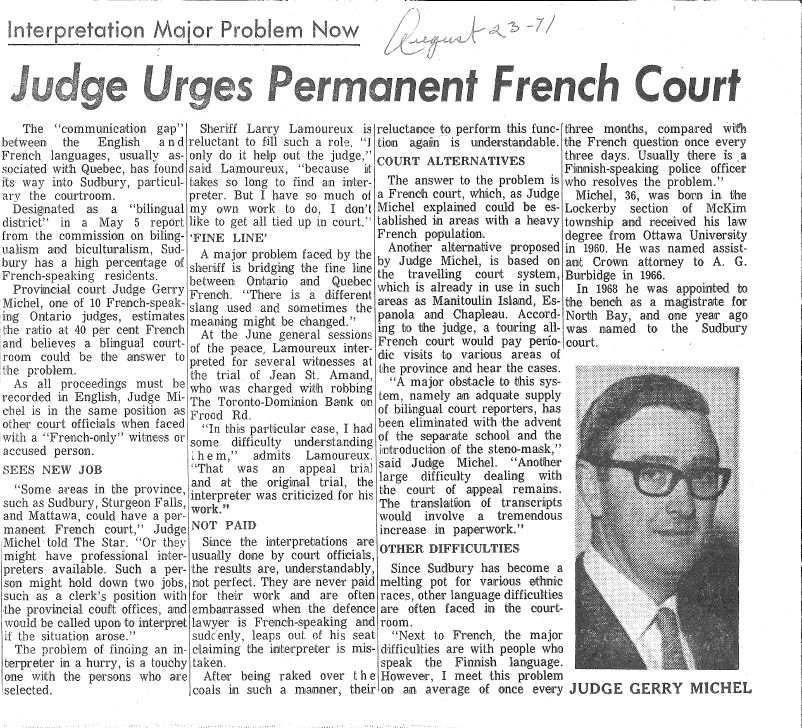

Le français et la Cour provinciale

Provincial Court (Civil Division), 1980-1990

For ten years – from June 1980 until September 1990 – Ontario had a Provincial Court (Civil Division) to adjudicate “small claims” cases. Civil lawsuits, where the amount claimed is less than a specified dollar amount, are often resolved in small claims courts. These courts are more informal than other courts and have less complex and technical procedures.

Pilot Project in Toronto

The Civil Division began as a three-year pilot project in the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto. The maximum claim was $3,000, as opposed to the $1,000 amount that applied to small claims courts elsewhere in the province. During the pilot phase, full-time judges appointed under the Small Claims Court Act were assigned to the Civil Division.

A Permanent Civil Division in Toronto

The Civil Division became permanent in January 1983, but still operated only in Metropolitan Toronto. At that time, the eleven full-time judges were formally sworn in as provincial court judges by the Chief Justice of Ontario.

Amalgamation of all Ontario Small Claims Courts

In 1985, all small claims courts were amalgamated into the Provincial Court (Civil Division). Although a single court, distinctions remained between Toronto (Judicial District of York) and the rest of the province. Notably, the maximum amount remained at $3,000 for Toronto and at $1,000 elsewhere.

Small Claims Court Transfer

On September 1, 1990, the Provincial Court (Civil Division) ceased to exist. In its place, the Small Claims Court became a branch of the Ontario Court (General Division) which later became the Superior Court of Justice. The former Civil Division judges did not become Superior Court judges as part of the transfer. They remained as provincial appointees who were assigned to the new branch.

The Ontario government stopped appointing full-time Small Claims Court judges in 1987. As of 2014, only two of these appointees remained on the bench and both were sitting part-time on a per-diem basis. Although Superior Court judges may sit in the Small Claims Court, the vast majority of cases are, in fact, heard by lawyers who serve as part-time deputy judges.

Profile: Chief Judge S. Douglas Turner

Douglas Turner became the Senior Judge when the Provincial Court (Civil Division) was established in 1980. He became Chief Judge when that position was created following the amalgamation of the Civil Division and Small Claims Courts in 1985. Before becoming a judge, Turner had worked for the Ontario Ministry of Commercial Relations where he had helped to draft the Business Practices Act, a ground-breaking consumer protection statute.

Turner also had the distinction of playing football for the Toronto Argonauts in 1947 and 1948. Ted Andrews, former Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division) recalled, “I liked Doug Turner. He was a big guy with huge feet. You wouldn’t know him for more than a few hours without learning he had been a linesman for the Argonauts football team. He was a congenial guy.”

Reflections: Pamela Thomson

In 1981, Pamela Thomson was appointed as a full-time Small Claims Court judge, assigned to the new Provincial Court (Civil Division). She was 37 at the time and one of a handful of provincially appointed female judges in Ontario. Thomson wanted to be a Small Claims Court judge to show people the power of mediation and emphasize sitting down to talk before trial. “We were the first court in Canada to do pre-trials”, says Thomson. “Our concept was later copied by many other courts in Ontario and beyond.” Thomson’s previous experience as a labour lawyer had convinced her that pre-trial processes to resolve issues would be in everyone’s best interest.

Thomson recalls the less than spacious quarters of the early days and the unusual assortment of court settings. On many occasions she presided over hearings in the auditorium of a Polish hall on the Lakeshore in Toronto. “That was fine in the morning until midday when the sausages would go on. The beer would come out at 1 o’clock and there would be all these people having lunch at the back of the auditorium while court was in progress.”

A group of Small Claims Court Judges being sworn into Provincial Court in 1983. From left to right, back row: Ronald Radley, Gordon Chown, Stewart Kingstone, Ben Lamb, T. Charles Tierney, Marvin Zuker. From left to right, front row: Douglas Turner, Moira Caswell, Gerald Vickers, Pamela Thomson, Reuben Bromstein. (Photo courtesy of P. Thomson)

Thomson recalls a hard-fought battle for full-time Small Claims Court judges to achieve parity with the Criminal and Family Division judges. She felt that the criminal bench, in particular, did not feel that Small Claims Court judges were entitled to be treated as “real judges.” She found the family bench, under the leadership of Chief Judge Ted Andrews, to be much more supportive.

In 1990, Attorney General Ian Scott called the full-time Small Claims Court judges to a meeting to describe the upcoming transfer to the Ontario Court (General Division). “Ian Scott’s idea was that the Small Claims Court was really important and that he would elevate the Court. He thought that the General Division justices would sit in Small Claims Court as part of their rotation, but that never happened.”

Reflections: Marvin Zuker

Marvin Zuker is the only provincially appointed Ontario judge who has sat full-time as a small claims, family, and criminal court judge. His first judicial appointment was to the Toronto Small Claims Court in 1978, two years before the Civil Division was created as a pilot project.

Like Thomson, Zuker was a strong believer in pre-trial resolution. During his 12 years in Small Claims Court, Zuker would often ask the clerk to bring litigants to his chambers at around 9:00 a.m. “My goal was to settle as many cases as possible before Court began at 10:00 a.m.”

Not all of Zuker’s cases were straightforward. In one instance, he issued a judgment in favour of civil rights activist Charles Roach who had sued the police in Small Claims Court. As Zuker recalls, “Roach, a black lawyer, had been stopped by the police near his office because they were looking for somebody black.” Zuker wrote a lengthy decision essentially saying that the police cannot stop someone simply on the basis of skin colour. The decision was ultimately upheld by the Ontario Court of Appeal.

Like many of his colleagues, Zuker was unhappy when the Small Claims Court was transferred in 1990 from a Civil Division of the Provincial Court, with its own Chief Judge, to become a branch of the federally appointed court. He said, tongue in cheek, that the status of the court was so diminished that it could more aptly be described as a “twig” rather than a “branch.”

Zuker found that his Small Claims Court experience was valuable in his subsequent family court work. Like a Small Claims Court judge, a family court judge can use an inquisitorial style, especially when parties are not represented. When Zuker came to criminal court, however, he had to learn a new style of judging. “I had to sit back and play a less active role in moving the case forward because almost everyone had lawyers.”

The Demise of The Trial De Novo

Until the late 1970s, the majority of appeals from decisions of the Family or Criminal Division of the Ontario Provincial Court were heard by way of trial de novo, or new trial, before a federally appointed judge in the District Court.[1] In criminal matters, this procedure applied to all summary conviction offences[2] and in family matters, to appeals under statutes such as The Deserted Wives’ and Children’s Maintenance Act and The Parents Maintenance Act. Appeals from decisions made by justices of the peace were also heard by trial de novo. In a trial de novo, both sides would present their evidence and arguments all over again, as if the Provincial Court trial had not occured. In fact, at the trial de novo before the District Court judge, either party was free to call new witnesses who had not testified at the original trial .

Appeal on the Record and Trial De Novo

An appeal from a trial decision ordinarily proceeds on the basis of the record before the tiral judge. The evidence the trial judge heard and the arguments made by counsel are recorded word-for-word by court reporters. These records are called transcripts or proceedings, and are provided to the appeal court along with the trial judge’s decision and reasons. Although it can review the transcripts of evidence, the appeal court generally does not make its own independent factual findings. Instead, the appeal court defers to the trial judge’s factual findings, on the baiss that the trial judge had the best opportunity to assess the credibility of various witnesses and the weight to be given to each piece of evidence. Ordinarily, the only questions in a appeal on the record will be whether the trial judge properly understood the law, and whether he or she properly applied the law to the facts that were found to exist.

In an appeal by way of trial de novo, the appeal court hears from witnesses directly – including, in some cases, witnesses who were not called at the original trial. Because the appeal court has its own opportunity to hear and consider the evidence in a trial de novo, it is not bound by the trial judge’s factual findings. The appeal court hearing a trial de novo will make its own factual findings, and then interpret the law and apply it to those facts. An appeal by way of trial de novo will therefore be much broader than an appeal on the record.

An appeal by way of trial de novo could be a benefit or a burden, depending on the outcome in the first trial and the resources of each party. For the losing party, a trial de novo provided an opportunity to address any weaknesses that became apparent during the original trial before the Provincial Court. Arguments could be strengthened and additional witnesses called to shore up the case. For the winning party, a trial de novo meant having to go to the trouble of another full hearing, simply to try to preserve the same outcome. For lawyers and for litigants who could readily afford the cost of multiple hearings, a trial de novo on appeal meant that the Provincial Court trial could be treated as a “practice run” – a chance to test their case and discover what evidence and arguments their opponents would be relying on, without the risk that they would later be bound by anything that happened there. This could be very useful for individuals charged with criminal offences, who at the time were not entitled to disclosure of the Crown’s case in advance of trial as they now are under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. For those litigants with fewer resources, however – including many accused persons – the expense associated with two full trials could be overwhelming.

“It was demoralizing to see some counsel doing an inadequate job before me, treating the proceeding as a form of discovery for a later trial in the County Court,” recalled George Thomson, who sat in Provincial Court (Family Division) as a judge in the 1970s and early 1980s. “For me, it represented a statutory declaration that the Provincial Court couldn’t be trusted to do its job well. Even more important, in family cases it could mean lengthy damaging delay for children and their parents.”[3]

New Rules for Appeals

Over time, appeal by way of trial de novo gave rise to increasing concern about inefficiency, waste of judicial resources, and potential abuse. In 1975 the federal government, led by Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, introduced an amendment to the Criminal Code that changed the procedure for appeal from a summary conviction proceeding. That amendment came into force in Ontario on November 1, 1977.[4] Under the new rules, which continue to apply today, summary convictions appeals from decisions of provincially appointed judges are almost invariably made on the basis of the existing record. The appeal court can examine the transcript of the witnesses’ evidence and the submissions made in the Provincial Court, but does not usually hear evidence itself and is largely bound by the trial judge’s factual findings. In certain circumstances, however, an appeal can still be heard by way of trial de novo, but this remedy is now rarely sought and rarely granted.[5]

During Parliamentary debates in late 1975 and early 1976, Members expressed mixed views of the proposed amendment to the Criminal Code. John Gilbert, the NDP Member of Parliament for Broadview-Greenwood who was himself a lawyer, observed: “From my experience many lawyers always welcomed the trial de novo, especially when they lost in the lower court, because it gave them a second chance to present their cases and probably to strengthen them.”[6] For his part, Claude-André Lachance, the Liberal Member of Parliament for Lafontaine-Rosemont, described the changes as “improvements which law practitioners had been requesting for some time,” noting that they would allow higher courts to “assess more easily the evidence introduced before a court of first instance, without the appellant having to establish again this evidence.”[7]

Not All Supported the Changes

One of the staunchest opponents of the change to the Criminal Code was Eldon Woolliams, the Progressive Conservative Member of Parliament for Calgary North. Prior to being elected to public office, Woolliams had been a celebrated criminal defence lawyer – the best defence trial lawyer of his day, according to his close friend and former Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Although Woolliams allowed that there had been some abuse of the trial de novo, “because lawyers sometimes would have a trial run before a provincial judge and then go to the district court,” he also stressed the importance of meaningful and searching review of Provincial Court decisions. His remarks reveal a great deal about how provincial courts functioned – or were perceived to function – during this period:

There is something I wish to point out which I know the minister and hon. Members who have practised law understand. In provincial courts, judges have to sit all morning. Anyone who attends these courts will realize how many cases a judge hears in a day. The judge does not have time to weigh all the pros and cons. There is, of course, the safeguard that in exceptional cases the whole thing can be reviewed by the [federally appointed judge of the] district court. In some cases the magistrate merely says, on the basis that the Crown witnesses and policemen are honest, that he finds the accused guilty. That is a finding of fact and there is no appeal unless there is a rehearing and a re-evaluation of the witnesses.

That is the weakness of our system.[8]

Trial De Novo and New Trial

Even though the words mean the same thing, a “trial de novo” is different from a new trial. A trial de novo is an appeal, whereas new trial is the result of a successful appeal. This may seem like a very fine distinction, but it has significant practical effects.

Imagine an accused person is convicted at trial. If that conviction is appealed by way of trial de novo, it remains in effect until the appeal court determines the outcome of the trial de novo.

The accused person may be convicted or acquitted at the trial de novo, but the original conviction stands until the trial de novo is concluded.

A new trial, in contrast, can only be ordered following a successful appeal. For an accused person who was convicted at trial, a successful appeal means that the conviction is overturned. Once a conviction is overturned, the person is once again presumed innocent unless and until he or she is convicted at the new trial.

Woolliams was pleased that the amendment would permit federally appointed judges to order an appeal by way of trial de novo in certain circumstances, but also expressed doubt that this provision would have much effect. In his view, federally appointed judges would generally not be inclined to grant a trial de novo since it would mean additional work for them:

Knowing judges as I do – many of them are good friends of mine and I hope they remain so – they are liable to say that they do not want all the hard work involved, and very often will not exercise the discretion. It will become a very rare discretion, if ever it is used.[9]

Interestingly, no such concerns were expressed in the provincial legislature when the Provincial Offences Act was introduced in 1979. Like the earlier amendments to the Criminal Code, the POA abolished appeals by way of trial de novo except in cases where the appeal court is of the opinion that a trial de novo will better serve the interests of justice. Even those Members of Provincial Parliament who expressed concern about this change, such as future Superior Court judge Albert Roy, recognized its importance in curbing abuses of the trial de novo procedure,[10] and none appear to have doubted the capacity of the Provincial Court to adjudicate regulatory offences fully and fairly.

Appeals in Family Law Matters

The amendments to the Criminal Code also affected appeals in family law matters. This is because several Ontario statutes administered by the Provincial Court (Family Division), such as The Deserted Wives’ and Children’s Maintenance Act[11] and The Parents’ Maintenance Act,[12] stated that an appeal from a Provincial Court decision had to be made in accordance with The Summary Convictions Act. The Summary Convictions Act in turn applied the Criminal Code provisions relating to appeals – including the provision that made every appeal from a Provincial Court decision a trial de novo.[13]

Ironically, elimination of the trial de novo came latest where it was needed most – in child protection matters where the impact of delay is greatest.[14] “Both judges of the Provincial Court (Family Division) and Children’s Aid Societies pressed strongly to have the change in appeal procedures applied to child protection cases,” said Thomson.[15] That change was finally made in 1979.[16]

New Appeal Procedures Have Stood the Test of Time

Today, as Eldon Woolliams predicted, it is indeed rare for an appeal from a Provincial Court decision to be heard by way of trial de novo. An on-the-record appeal is now the primary procedure for review of a Provincial Court decision by a higher court, and a trial de novo has become the exception.[17] Contrary to Woolliams’ concern, however, this is not because applications are being routinely dismissed by higher court judges anxious to avoid the work involved in hearing and adjudicating the same matter over again. Rather, it is because almost no one applies for a trial de novo. Since 1977, there have been only a handful of reported cases in Ontario in which appeal by way of trial de novo has been sought.[18] It appears that litigants have not commonly shared Woolliams’ view that the Provincial Court lacked the time and judicial independence required to render balanced and considered judgments.

- Prior to 1990 in Ontario, there were three separate trial courts: 1) Provincially appointed judges sat in the Provincial Court at different locations throughout the province, 2) One or more federally appointed District Court judges were assigned to the District Court in the county town of each judicial district and 3) A large number of federally appointed High Court Judges sat primarily in Toronto but also sat on assize as needed in county towns to deal with High Court cases.↩

- Indictable offence appeals have always gone directly to the Ontario Court of Appeal.↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1975, 1974-75-76 (Can.) c. 93, s. 94.↩

- The party requesting trial de novo must satisfy the appeal court that the interests of justice would be better served by a trial de novo than by an appeal on the record, either because of the condition of the trial record or for some other reason.↩

- Ontario Hansard, November 18, 1975, p. 9214. ↩

- Ontario Hansard, November 19, 1975, p. 9247. ↩

- Ontario Hansard, January 27, 1976, p. 10356. ↩

- Ontario Hansard, January 27, 1976, p. 10356. ↩

- Ontario Hansard March 13, 1979; March 27, 1979. ↩

- R.S.O. 1970, c. 128, s. 13. ↩

- R.S.O. 1970, c. 336, s. 6. ↩

- R.S.O. 1970 c. 450, s. 3. ↩

- The Child Welfare Act, R.S.O. 1970, s. 36(4) provided that an appeal from a child protection order “shall be a hearing de novo and the judge may rescind, alter or confirm the decision being appealed or make an order or decision that ought to have been made.” ↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- New appellate provisions were introduced in An Act to revise the Child Welfare Act, S.O. 1978, c. 85, s. 43, which came into force on June 15, 1979. ↩

- See R. v. R.N.-Z.M., [2005] O.J. No. 5497. (S.C.); R. v. Elias, [1980] O.J. No. 1523 (Div. Ct.); R. v. Prasad, [1995] B.C.J. No. 1829 (S.C.); R. v. Ford, [1987] P.E.I.J. No. 29 (S.C.); R. v. Faulkner (1977), 37 C.C.C. (2d) 26 (N.S. Co. Ct.); R. v. Carelli, [1978] M.J. No. 246 (Co. Ct.); R. v. Salomon, [1995] O.J. No. 3268 (Gen Div.); R. v. Mackie, [2001] B.C.J. NO. 2887 (S.C.). ↩

- See R. v. R.N-Z.M., supra; R. v. Geisbrecht, [1978] O.J. No. 3768 (Co. Ct.) (Crown application for trial de novo dismissed); R. v. Steinmiller, [1979] O.J. No. 856 (C.A.) (matter remitted to summary conviction appeal court for trial de novo); R. v. Elias, [1980] O.J. No. 1523 (Div. Ct.) (appeal from refusal to grant trial de novo dismissed on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to support the request); R. v. Lapierre, [1980] O.J. No. 1974 (Dist. Ct.) (trial de novo ordered where a Francophone accused was originally tried in English); R. v. Sheridan, [1990] O.J. No. 359 (C.A.) (accused was acquitted by a Justice of the Peace of various provincial offences; the Crown appealed and applied for a trial de novo on the basis that part of the transcript had been lost; Provincial Court ordered a new trial. The Court of Appeal held that the Provincial Court judge should either have ordered a trial de novo before himself on the basis of the lost transcript, or, if he was of the opinion that the acquittal could not stand, ordered a new trial); R. v. Hilderley, [1990] O.J. No. 560 (Dist. Ct.) (accused sought trial de novo on appeal from Provincial Offences Act convictions entered by a Justice of the Peace; Provincial Court judge affirmed convictions on the record; on further appeal the District Court ordered a new trial); R. v. Sebastian, [1999] O.J. No. 1329 (Gen. Div.) (application for trial de novo dismissed); R. v. Hanneman, [2001] O.J. No. 839 (S.C.) (application for trial de novo on the basis of problems with the transcript of original trial dismissed but alternative remedy ordered); R. v. MacDonald, [2007] O.J. No. 3551 (S.C.) (trial de novo ordered and held where there was no transcript of the original hearing). ↩

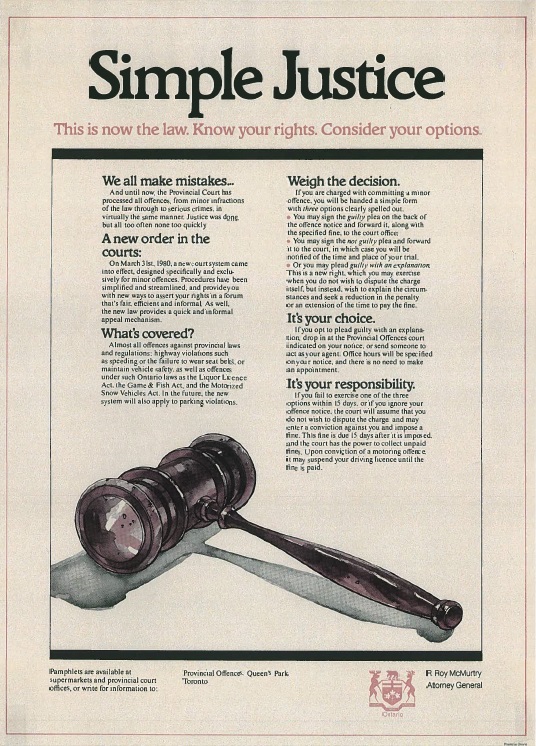

Simple Justice: The Introduction of the Provincial Offences Act

Provincial Offences Act. It appeared in courthouses, public buildings and newspapers across the province.” width=”350″ height=”487″>

This is a poster, published by the Ministry of the Attorney General, announcing the introduction of the Provincial Offences Act. It appeared in courthouses, public buildings and newspapers across the province.The Provincial Court was profoundly changed on March 31, 1980, when the Provincial Offences Act (POA) came into force. At the time, the POA was described as “one of the most sweeping legislative reforms of procedures governing the prosecution of offences since the enactment of the Criminal Code in 1892.”[1] The POA established a comprehensive, self-contained code of procedure for prosecuting and enforcing regulatory offences in provincial statutes and regulations and municipal by-laws.

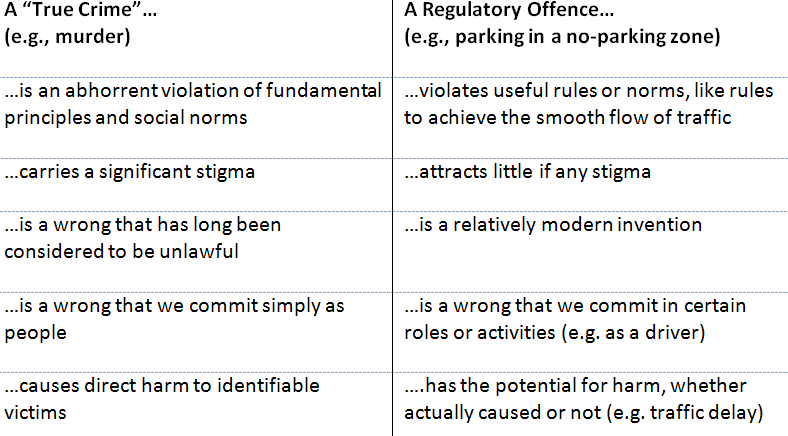

The POA replaced a complex and convoluted system with one “designed specifically and exclusively for minor offences.”[2] It was “the first attempt in Canada to create a procedural framework, which at each stage recognizes and responds to the important distinctions between provincial offences and true crimes.”[3]

“Persons who breach provincial laws have to be prosecuted and the offences have to be fairly and firmly interpreted, but offenders ought not be treated like criminals, whether inadvertently or by association”

(Douglas Drinkwalter & Douglas Ewart, Ontario Provincial Offences Procedure (Toronto: The Carswell Company Limited, 1980), p. iii)

Our Lives Are Regulated

In R. v. Wholesale Travel Group Inc., a case involving the regulatory offence of false or misleading advertising, the Supreme Court of Canada had this to say about regulatory law:

It is difficult to think of an aspect of our lives that is not regulated for our benefit and for the protection of society as a whole. From cradle to grave, we are protected by regulations; they apply to the doctors attending our entry into this world and to the morticians present at our departure. Every day, from waking to sleeping, we profit from regulatory measures which we often take for granted. On rising, we use various forms of energy whose safe distribution and use are governed by regulation. The trains, buses and other vehicles that get us to work are regulated for our safety. The food we eat and the beverages we drink are subject to regulation for the protection of our health.

In short, regulation is absolutely essential for our protection and well being as individuals, and for the effective functioning of society. It is properly present throughout our lives. The more complex the activity, the greater the need for and the greater our reliance upon regulation and its enforcement. … Of necessity, society relies on government regulation for its safety.

(R. v. Wholesale Travel Group Inc. (1991), 67 C.C.C. (3d) 193 at pp. 239-240 per Cory J.)

What Is A Provincial Offence?

To fully appreciate the significance and impact of the POA, it is important to understand what provincial offences are and how they differ from criminal offences. A provincial offence is a violation of a provincial regulatory law or a municipal by-law passed by a town or city council. Unlike criminal law, which prohibits certain activities, laws such as the Highway Traffic Act, the Occupational Health and Safety Act, and the Food Safety and Quality Act, regulate activities that are otherwise lawful and often quite useful to society. Although a small number of provincial offences carry heavy fines or even the risk of imprisonment on conviction, most penalties are relatively minor. One common and familiar example of a provincial offence is a parking infraction.

By the mid-1970s, the Law Reform Commission of Canada estimated that the statutes and regulations of any one province created, on average, 18,540 offences, not including those created by municipal by-laws. When by-law offences are added into the mix, the total number of provincial offences increases dramatically.

Municipal By-Laws

By-law offences are classified as provincial offences because the power to create by-laws is delegated by the province under provincial statute.

The provincial Municipal Act gives municipalities the power to pass by-laws governing a wide range of matters including highways, transportation, waste management, parks, structures, animals, and business licensing, as well as more generally for the “economic, social and environmental well-being of the municipality,” the “health, safety and well-being of persons,” and the “protection of persons and property, including consumer protection.”

We sometimes speak of a “hierarchy of laws,” with federal statutes like the Criminal Code at the top, provincial statues in the middle, and municipal by-laws at the bottom, but that doesn’t mean that municipal by-laws are unimportant. In fact, municipal by-laws govern many of our everyday activities.

The number and scope of by-laws vary depending on the size and nature of each municipality, but for a large urban centre like Toronto or Ottawa, municipal by-laws can number in the tens of thousands.

Municipal by-laws create a wide range of offences, from building a fence too high to keeping too many dogs or making excessive noise. These offences are prosecuted under the POA.

Pre-1979 – Summary Conviction Process

In Ontario, prior to the introduction of the POA, all provincial offences – no matter how minor – were prosecuted under the Summary Convictions Act. The Summary Convictions Act in turn adopted the procedure set out in the Criminal Code for summary conviction offences. That meant that parking tickets, for example, were dealt with in the same courts and according to the same rules as far more serious offences. This was no small matter. By the late 1970s in Metropolitan Toronto alone nearly three million parking tickets were being issued each year, with 60 per cent of them – approximately 1.8 million – requiring at least some court process for collection.[4] If the entire court process was required, the cost of enforcing an unpaid parking ticket ranged from $50 to $75 – at a time when the usual penalty was a $5 or $10 fine.[5]

In addition to being a relatively expensive process and treating minor offenders like “criminals,” using the summary conviction procedure to prosecute provincial offences also imposed enormous financial and workload pressures on the provincial court. As then-Attorney General Roy McMurtry observed in 1978:

“Few people realize that the real administrative and workload burden on our justice system comes not from complex criminal trials, but rather from the ever-increasing flood of minor offences which is threatening to engulf the administration of justice in this province.

The problem is volume. While in one year the Ontario courts receive about a quarter of a million criminal offences, they’re hit with more than three and one half million provincial offence charges. Because the basic structure of the current provincial offence procedure is the same as the criminal procedure employed in a murder trial, and because the paperwork burden is similar, minor offences are being tried in a manner which clogs the courts. This inevitably leads to multiplying adjournments and delay for defendants, together with ever-mounting costs for both defendants and the taxpayers of this Province.”[6]

Bringing the entire weight of criminal procedure to bear on such minor offences as parking tickets was not only administratively burdensome; it also risked bringing the administration of justice into disrepute. Frank Devine, who became a justice of the peace in 1971, describes shortcuts taken in an attempt to speed the process along, but notes these came at a cost:

“Under the Summary Convictions Act, all speeding tickets had to go through a full trial – even if the accused chose not to appear. Following the proper procedure for each trial would have meant that only a small fraction of the cases before the court would be heard each day. Instead, a single police officer – a ‘radar man’ – would be sworn in on all of the matters on the docket that morning, and testify about a pile of documents recording the speed at which each defendant was travelling. The court could process dozens of these an hour, with some cases taking as little as a minute. The court was trying to be efficient and prevent a total breakdown of the system, but cutting corners like this made a mockery of the officer’s oath and turned court proceedings into a farce.”[7]

A New Approach to Provincial Offences

By the early 1970s it was clear that radical change was required. In 1973, a committee was struck to identify ways to reduce the number of persons jailed for non-payment of fines for provincial offences. The original committee members were Archie Campbell, then Crown Counsel for Criminal Appeals and Special Prosecutions,[8] Douglas Drinkwalter, Crown Attorney for the Judicial District of Norfolk, and Justice Norman Nadeau of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). This was one of the first times a sitting judge participated in a law reform and policy development committee, and his first-hand experience of day-to-day challenges faced by the Provincial Court was no doubt invaluable to the committee’s efforts. In 1975, Doug Ewart, then counsel in the Criminal Law Division and Policy Development Division of the Ministry of the Attorney General, began to assist the committee, which soon broadened its mandate to cover “all aspects of provincial offence proceedings.”[9]

By 1978, the committee had designed and received approval for “comprehensive reforms.”[10] In March 1979, the POA was passed. Its coming into force was delayed for a year, however, in order to allow time to implement new court systems and procedures and provide training to justice system participants — ranging from judges and court personnel to provincial and municipal police. Finally, in March 1980, the POA replaced the Summary Convictions Act, “opening a whole new era in provincial offence procedure in Ontario.”[11]

The POA was intended to create a procedure that reflects the distinction between provincial offences and criminal offences[12] and to foster “convenience, clarity, efficiency, and simplicity.”[13] Under the POA, all provincial offences are dealt with in the same fashion if and when they come to trial. Prior to trial, however, the POA distinguishes amongst methods of proceeding with offences. One category includes 90 per cent of provincial offences that are relatively minor in nature, such as failing to come to a full stop at a stop sign or failing to properly maintain one’s yard. Another comprises 10 per cent of offences – such as environmental protection offences, major construction safety violations, security trading offences, consumer protection offences, and serious driving offences – that are more serious, both in terms of the harms they cause and the penalties they warrant. While the more serious provincial offences continue to be governed by a more formal and detailed framework akin to the summary conviction procedure, most provincial offences are governed by a simplified procedure.

A Range of Procedures for a Range of Offences

The POA contains three procedural streams that correspond to different categories of provincial offences.

Part I of the POA applies to routine minor violations – such as failure to wear a seatbelt – that are prosecuted by a certificate of offence.

Part II of the POA covers parking infractions, prosecuted by a certificate of parking infraction.

Part III of the POA covers more serious offences – for example, a violation of the Occupational Health and Safety Act that resulted in severe injury to a worker. These are prosecuted by laying an information, much like Criminal Code offences.

As Doug Ewart observes, “The offences covered by the three parts of the Act ranged from speeding tickets to multi-million dollar pollution offences.” The creation of three procedural streams helps to ensure that the process adopted for each offence corresponds to its gravity.

(Interview of D. Ewart for OCJ HIstory Project, 2014)

Under the POA, proceedings for minor offences are commenced by a police officer or provincial offences officer giving the person charged a “certificate of offence,” often referred to as a “ticket.” A person disputing that he or she committed the offence described in the certificate could now request a trial simply by checking the appropriate box on the back of the notice and submitting it by mail. A person wishing to plead “guilty” could also now do so and pay the associated fine by mail (or today, online) without having to attend court. The POA also made it possible to plead “guilty with an explanation” without needing to attend court at a set date and time. A person could go to court at his or her convenience, meet informally with a justice of the peace, and give an explanation or request additional time to pay the fine. The justice of the peace then assessed the appropriate penalty in light of the person’s submissions.

These measures may now seem entirely commonplace – indeed, only too familiar to those of us who have had to deal with parking tickets or other minor offences – but at the time they were profound innovations. In fact, some thought certain aspects of the new regime went too far. For example, if a person simply didn’t respond to a ticket – in other words, he or she did not select any of the three options set out above – he or she would be found guilty of the offence without the need for a trial. Doug Ewart recalls, “The idea that you could give someone a ticket and if they didn’t respond they could be convicted was shocking to the criminal bar.”[14]

A New Element of the Court

At the same time as it implemented these changes, the Ontario government adopted the Provincial Courts Amendments Act. The legislation created the Provincial Offences Courts as a separate division of the Provincial Court with exclusive jurisdiction over all provincial offences. Previously, provincial offences had been tried in the Provincial Court (Criminal Division), with the result that persons charged with provincial offences – even very minor ones – would find themselves sharing courtrooms with individuals charged with serious crimes.

The distinction between Provincial Offences Courts and criminal courts – like the distinction between provincial offences procedure and criminal procedure – was intended to ensure provincial offences could be addressed with “much less rigidity and formality”[15]than crimes – and without the stigma commonly associated with criminal proceedings. As Drinkwalter and Ewart wrote, the creation of the Provincial Offences Court was intended to accomplish two goals:

“[F]irst, persons charged with provincial offences will not await arraignment alongside persons charged with robbery, rape and murder; second, it is anticipated that, over time, prosecutors and judicial personnel will come to associate the Provincial Offences Court with a different mind-set and approach. With an entirely different type of offence and offender before it, the court can relax some of the attitudinal rigidity which may be necessary in courts dealing with criminal offences. Persons who breach provincial laws have to be prosecuted and the offences have to be fairly and firmly interpreted, but offenders ought not be treated like criminals, whether inadvertently or by association.”[16]

The task of cultivating this new and different approach fell primarily on the shoulders of justices of the peace, who heard most of the cases in Provincial Offences Court.

Impact On the Work of the Provincial Court

The POA significantly expanded the role of both justices of the peace and judges of the Provincial Court, although it affected the work of justices of the peace much more extensively. From the outset, POA matters were ordinarily tried by justices of the peace, and a decision of a justice of the peace in a POA trial could be appealed to a judge of the Provincial Court. The POA thus made the justice of the peace bench a trial court, and the Provincial Court judges bench an appeal court. Both faced challenges in growing into these new roles.

With justices of the peace handling most trials, the need for education was vital, as George Thomson recalls:

When I was Deputy Minister of Labour, we were always concerned that many justices of the peace did not understand the importance, in both real and symbolic terms, of prosecutions against employers and employees who violated health and safety regulations. Often these cases were handled quickly, with small fines for activity that had major implications for workplaces across the province. Our sense was that the education of justices of the peace did not adequately bring home the importance of their role under the new legislation.[17]

In fact, for an extended period, it was simply assumed that justices of the peace would learn on the job. Andrew Clark, the Senior Advisory Justice of the Peace for Ontario from 2004 to 2014, recalls that when he was sworn in as a justice of the peace in 1987 he was expected to begin work the next day – presiding over POA matters in night court at Old City Hall in Toronto – without any formal training at all. At his swearing-in ceremony, Clark raised his hand and asked Chief Judge Hayes if he could “shadow” a sitting justice of the peace. He was allowed to do so for several weeks, and “shadowing” is now a routine part of the training that new justices of the peace experience.[18]

Clark was a lawyer before becoming a justice of the peace, and therefore already had experience interpreting statutes and cases. The same was not true of most of his colleagues. Justices of the peace are “not traditionally lawyers” but instead “come from all walks of life.”[19] At the time the POA and Provincial Courts Amendment Act took effect, virtually none of the sitting justices of the peace and very few new appointees were legally trained. A great deal of commitment, hard work and perseverance was required of justices of the peace, who were suddenly expected to become familiar with, and effectively and fairly apply the hundreds of statutes and by-laws covered by the POA. They were assisted in this process by members of the committee that had developed the POA, who travelled across the province providing training to prepare justices of the peace for the coming into force of the POA.

The judges of the Provincial Court faced their own difficulties in exercising their new appellate role. Provincial Court Judge Rick Libman was a Crown Attorney at the time these changes came into effect, and describes the appeal procedure as cumbersome:

“The testimony heard before a justice of the peace in Provincial Offences Court was recorded but it wasn’t transcribed. That meant that if a decision of a justice of the peace was appealed, a Provincial Court judge would have to listen to the recording in order to know the evidence. The tapes were sometimes lengthy and often there were equipment malfunctions or other issues, so parts would be inaudible. As a Crown Attorney I found it incredibly time-consuming and often frustrating to have to review these tapes in order to prepare for an appeal, and I’m sure judges found it an equally vexing process.”[20]

Complex Justice: Liability and Penalties

Provincial Offences Act proceeding was included in Minor Offences, a Ministry of the Attorney General publication explaining the new legislation and procedures.” width=”300″ height=”273″>

This drawing of a Justice of the Peace hearing and recording a Provincial Offences Act proceeding was included in Minor Offences, a Ministry of the Attorney General publication explaining the new legislation and procedures.Although the POA was billed as “simple justice,” administering it was a complex role for justices of the peace to take on. Justices of the peace have been described as “the workhorses of the provincial regulatory system,”[21] enforcing hundreds of statutes ranging from the Highway Traffic Act to the Occupational Health and Safety Act to the Environmental Protection Act. And while provincial offences are distinct from “true crimes”; they still require that the court determine liability — that is, whether the defendant is guilty of the offence – and decide on an appropriate penalty. Those questions can be very complicated, both factually and legally, and pose specific and unique challenges in the context of regulatory offences.

In criminal proceedings, the Crown Attorney bears the burden of proving that the defendant not only committed the act alleged but did so “intentionally or recklessly, with knowledge of the facts constituting the offence, or with wilful blindness toward them.”[22]This is referred to as having a “guilty mind” or mens rea. For regulatory offences like those covered by the POA, in contrast, there is no requirement of mens rea. For some provincial offences, the only question is whether the defendant did the act alleged. These are called “absolute liability” offences.

In R. v. Sault Ste. Marie, a case decided in 1978 – shortly before the POA came into effect – the Supreme Court of Canada held that there should be a middle ground between crimes and absolute liability offences.[23] Most provincial offences fall into this middle ground, called “strict liability.” Once the Crown Attorney has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed the act, it is then open to the defendant to prove, on a balance of probabilities, that he or she took reasonable care to prevent the harm from occurring, or, in other words, was not negligent. This is often referred to as a “due diligence” defence.

For example, a defendant charged with a violation of the Occupational Health and Safety Act for allowing dangerous machinery to be operated without properly functioning protective equipment might show that he or she took reasonable care by conducting regular inspections of the machinery, holding training sessions to educate workers about the importance of the protective equipment, and instituting a policy that required all protective gear to be checked at the beginning of each shift. In these circumstances, even if the Crown Attorney could prove that the protective equipment failed, the defendant would almost certainly be acquitted.

At first glance, it would seem to be a good thing for individuals charged with provincial offences to have the possibility of a due diligence defence. Justice of the Peace Susan Hoffman, who is also a Special Lecturer in Regulatory Offences at the University of Windsor Law School, explains the reality was far different. “Neither the general public nor, in many cases, members of the legal community fully appreciated the substantive and procedural impact of the Sault Ste. Marie decision. A lot of cases came down to a company’s or an individual’s inability to lay out a due diligence defence. Often a justice of the peace would be hearing a trial and a witness would refer to documents – employee policies, for example, or correspondence – that seemed to suggest that a due diligence defence might be available, but those documents wouldn’t be introduced into evidence. This was especially true in cases in which the defendant was self-represented.”[24] And the vast majority of people appearing in POA courts were self-represented, as they are today.[25]

Not only did justices of the peace have to interpret and apply the new strict liability standard that is unique to regulatory offences, they frequently had to do so without the assistance of counsel and without all of the evidence that might be available.

Justices of the peace also had to craft appropriate penalties for those convicted of provincial offences, and at this stage, too, they faced unique challenges. The Criminal Code sets out a number of sentencing principles, including denouncing the unlawful conduct, deterring both the offender and other persons from committing offences, rehabilitating offenders, and promoting a sense of responsibility and acknowledging the harm done to victims and the community. When a judge issues a sentence for a Criminal Code offence, he or she can look to all of those principles for guidance. In the 1982 case of R. v. Cotton Felts, the first sentencing appeal under the POA to reach the Ontario Court of Appeal, the court held that general deterrence was the primary objective of sentencing under the POA. In other words, a sentence imposed for a POA offence should first and foremost deter the general public from committing such an offence.

It is certainly understandable that the objective of general deterrence is “particularly applicable to public welfare offences where it is essential for the proper functioning of our society for citizens at large to expect that basic rules are established and enforced to protect the physical, economic and social welfare of the public.”[26] At the same time, it can be very difficult to balance that goal against the circumstances of individual offenders. A fine that is large enough to deter the general public from committing an offence may totally bankrupt an individual on a fixed income. Moreover, whereas the Criminal Code sets out a sentencing range for each offence, most laws covered by the POA do not provide any such guidance. For these reasons, the task of crafting a fit sentence can be far more challenging for a justice of the peace sitting in Provincial Offences Court than for a judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division).

In some respects, streamlining the process for defendants made the work of the court more challenging. In the criminal context, an accused entering a guilty plea must appear before a court. The court will be advised of the specific facts of the offence and the circumstances of the offender, and will have a chance to ask for any further information that may assist in reaching the decision on sentencing. Recall that as a result of the changes made by the POA, a defendant who wished to plead guilty to a provincial offence could do so simply by checking the appropriate box on the notice or ticket and returning it by mail. But what penalty should be imposed on those who did not choose to go to trial? The only fair solution was to impose a fixed and automatic penalty for each offence. This too involved a great deal of work for the court. As Doug Ewart has noted, “The Chief Judge of the Provincial Court had to come up with a standard penalty (“set fine”) for hundreds of offences. A ‘set fine’ was a new concept, and determining the appropriate “set fine” for each offence was a new role.”[27]

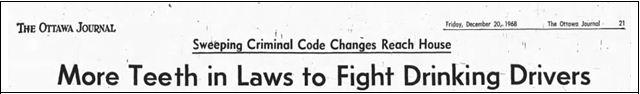

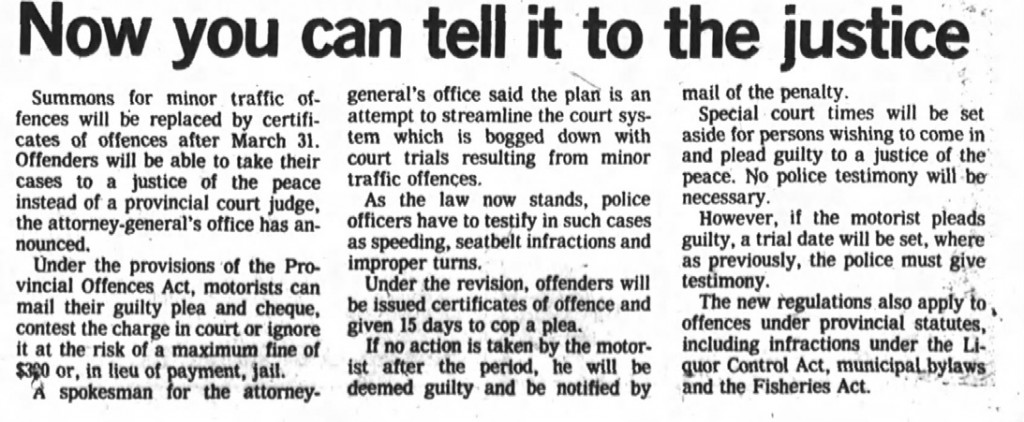

This article appeared in The Ottawa Journal. Given the profound changes the POA brought to the justice system, the new legislation received extensive coverage in the newspapers of the day. The Ottawa Journal published a correction to this article. In the second-last paragraph of this story, it should have read: “if a motorist pleads NOT guilty, a trial date will be set.” (The Ottawa Journal January 22, 1980.)

A Balancing Act

Achieving “simple justice” requires finding an appropriate balance between efficiency on the one hand, and procedural fairness on the other. Striking that balance is rarely easy and maintaining it can be even more difficult. In 1980, the POA shifted the balance significantly in favour of increased speed and informality. At the time, there was general agreement that this was a much needed and profound transformation to the justice system in Ontario. As George Thomson explains, “It was clear to everyone at that time that reform was absolutely essential if the court system was not to become totally paralyzed.”[28] Whether, in fact, the POA met its goal of simplifying court processes and procedures while preserving justice would be determined over the years that followed.

- Douglas Drinkwalter & Douglas Ewart, Ontario Provincial Offences Procedure (Toronto: The Carswell Company Limited, 1980), p.iii ↩

- “Simple Justice” poster. This poster was prepared by the Ministry of the Attorney General to announce the introduction of the POA. It was posted in courthouses and published in newspapers across Ontario. ↩

- Drinkwalter & Ewart, Provincial Offences Procedure, p. ii. ↩

- Ministry of the Attorney General, Provincial Offences Procedure: An Analysis and Explanation of Legislative Proposals (Ontario: Ministry of the Attorney General, April 1978), p. 20. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ministry of the Attorney General, Provincial Offences Procedure: An Analysis and Explanation of Legislative Proposals (Ontario: Ministry of the Attorney General, April 1978), p. 3. ↩

- Interview of F. Devine for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Campbell later served in a number of other roles, including Deputy Attorney General, Provincial Court judge, and Superior Court judge. He also presided over inquiries into the Ontario SARS outbreak and the police investigation of Paul Bernardo. ↩

- Drinkwalter & Ewart Provincial Offences Procedure, p. vi. ↩

- Drinkwalter & Ewart Provincial Offences Procedure, p. vi. ↩

- Drinkwalter & Ewart, Provincial Offences Procedure, p. vii. ↩

- Ministry of the Attorney General, Minor Offences, p. 2. (A booklet published at the time the POA was enacted.) ↩

- Ministry of the Attorney General, Provincial Offences Procedure: An Analysis and Explanation of Legislative Proposals (Ontario: Ministry of the Attorney General, April 1978), p. 6. ↩

- Interview of D. Ewart for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Ministry of the Attorney General, Provincial Offences Procedure: An Analysis and Explanation of Legislative Proposals (Ontario: Ministry of the Attorney General, April 1978), p. 92. ↩

- Drinkwalter & Ewart Provincial Offences Procedure, preface. ↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Interview of Andrew Clark for OCJ History Project, 2014 ↩

- Ontario Justice Education Network, Update, Fall/Winter 2005, p. 2. ↩

- Interview of R. Libman for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Jamie Cameron, “A Context of Justice: Ontario’s Justices of the Peace – From the Mewett Report to the Present” (2013). Comparative Research in Law & Political Economy. Research Paper No. 44/2013. p. 18 ↩

- R. v. Ste. Sault Marie, [1978] 2 S.C.R. 1299, p. 1309. ↩

- R. v. Sault Ste. Marie ↩

- Interview of S. Hoffman for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Interview of Andrew Clark for OCJ History Project, 2014 ↩

- R. v. Cotton Felts Ltd. (1982), 2 C.C.C. (3d) 287 at [need to get actual reporter to determine page number] ↩

- Interview of D. Ewart for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Interview of G. Thomson for OCJ History Project, 2014 ↩

Moving Bail Hearings from Jails and Police Stations to Courthouses

Inappropriate Surroundings

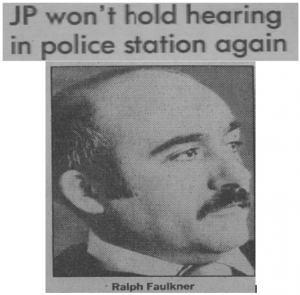

“We the find surroundings so dismal and so inappropriate that Justice of the Peace R.E. Faulkner simply refused to allow the proceedings – bail hearings – to continue. It was not just that the reception area for prisoners at the Don Jail (a room used for delousing and rectal examinations) contributed to a bleakness of atmosphere; it meant the exclusion of members of the public from a process which is supposed to be open.”

The Globe and Mail, Editorial, October 31, 1980

Two decisions by justices of the peace that had a profound impact on the Ontario Court of Justice have received little attention over the years. In 1980, Justice of the Peace Ralph Faulkner made a decision that resulted in thousands of citizens being spared improper and possibly illegal time in jail. Faulkner’s decision, along with a decision by Justice of the Peace P. Deacon in 1989, were catalysts in opening courts to the public and the press by moving bail hearings from jails and police stations to proper courtrooms.

Hearings in the Don Jail

In 1980 and before, bail courts were set up in Toronto’s Old City Hall on weekdays and Saturdays. People arrested on Friday and not released by that evening were typically held overnight in a single cell in a police station and then taken before a judicial officer presiding in the Saturday bail court at Old City Hall. These detainees were accorded their legal rights and many were able to obtain release on bail. However, no bail courts operated at Old City Hall on Sundays. To deal with that situation, a person arrested Saturday evening or early Sunday morning was taken to Toronto’s Don Jail – not a cell in a police station – put through an invasive body search at the jail and routinely held, often in shared cells, until Monday morning. For many people, this resulted in an extra day in jail.

The Criminal Code required – and continues to require – an arrested person to be brought before a justice within 24 hours or as soon as practicable. It was to comply with this requirement – and to assist the police in getting people out of the holding cells in the various police stations – that people arrested on a Saturday night or early Sunday morning were taken directly to the Don Jail. A justice of the peace was assigned to attend at the jail on Sunday mornings for hearings involving people arrested that morning or the night before. The justices of the peace would routinely remand the accused person to appear on Monday morning in one of the various bail courts located in courthouses throughout Toronto. Because the person had no access to counsel, there was no possibility of a full bail hearing in the jail to determine whether the person should be released or not. The jail was not open to the public or press. A Crown Attorney or duty counsel were not present. If a friend or relative contacted a police station on a Saturday evening looking for someone who had been arrested, they were advised the person would be attending a bail court on Monday morning. There was no mention of the Sunday so-called “bail court” held in the Don Jail.

Senior members of the judiciary were made aware of the conditions at the Don Jail and the fact that these proceedings held there were not open to the public. Despite this knowledge, justices of the peace continued to be assigned to the jail on Sunday mornings for these proceedings. But on Sunday, October 26, 1980, Justice of the Peace Faulkner arrived at the Don Jail, duly convened a hearing and declined to exercise jurisdiction over the 16 prisoners in custody at that time. “Would you not agree,” Faulkner asked during the proceedings, “we’re sitting here in the bowels of the jail?” “Yes, I would agree,” responded the staff sergeant who was acting in the capacity as prosecutor. Faulkner continued as follows:

“We have here no defence counsel, there are no legal aid representatives, there are no members of the public present, including the press and there can be no witnesses present to give evidence or speak on behalf of the accused. What is alarming…is the fact that none of these persons would be allowed admittance to these proceedings…The open court provides some safeguards against unjust or unfair proceedings against an accused. It certainly maximizes the chances of an equal and impartial administration of justice to all persons. These basic rights of the accused in public deserve our constant attention.

On the basis of the facts already described, it is my opinion that I would not be complying with fundamental legal principles or the requirements of the statutes if I were to attempt to hold court here and now. For these reasons, I am refusing to exercise jurisdiction until proper facilities are made available with the courtroom or place being open to the public and where the court can effectively exercise its authority and preserve order.”[1]

The Attorney General made no attempt to appeal this decision or to seek any order to continue the practice and Chief Judge Hayes was forced to move these hearings out of the Don Jail.

Justice of the Peace Faulkner exhibited considerable courage in making that decision. At that time, the Justices of the Peace Act was far different than it later became. No Justice of the Peace Review Council was in place to deal with complaints against justices of the peace. There was no requirement for a public hearing before a justice of the peace could be removed from office. In effect, justices of the peace were appointed to office at the pleasure of the Lieutenant Governor in Council. Fortunately, once Faulkner’s decision became public, it was widely reported and enjoyed support in the media. Further, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association strongly supported the decision.

Hearings in Police Stations

Unfortunately, the solution to the problem devised by the Chief Judge and officials of the Ministry of the Attorney General was almost as bad as holding the hearings in the Don Jail. Sunday hearings were moved to four police stations in Toronto. The police stations were not equipped with accommodations that could be used to function as a courtroom. Public access was still an issue as the various rooms selected in police stations for these hearings could barely accommodate the participants and left almost no room for observers from the public.

The transcript of the proceedings in R. v. Sytron, heard on April 9, 1989 before Justice of the Peace P. Deacon, vividly highlights the folly of attempting to hold bail hearings in a police station. “I would be pleased to know why we have to be in the back room of a police station where really the public, if they had access, couldn’t get in the room,” stated Deacon. “There is no room for them. I note we have whiskey bottles behind us. We have the tailgate of a truck beside us. There must be a hundred empty courtrooms in this community today. Is there some reason why we have to be down here?…the spirit of the law certainly is being offended by calling this an open bail hearing.”[2] The whiskey bottles and truck tailgate were in fact exhibits to be used in another proceeding but all agreed that the room was not open to the public and Deacon refused to proceed with the bail hearing.

In early 1992, an official of the Toronto Police Service recommended to the senior judiciary, including Chief Judge Sidney Linden, that the bail hearings held in courtrooms at the Old City Hall on Saturdays could be moved into these police stations and dealt with as those held on Sundays. This plan would have made a bad situation even worse. Fortunately, this plan was not implemented and, shortly afterwards, bail courts were moved out of police stations and into courthouses.

The decisions of Justice of the Peace Faulkner in 1980, and Justice of the Peace Deacon in 1989, were the catalysts that led to all bail hearings – no matter what the day – being heard in an open court. Further, Faulkner’s decision resulted in thousands of accused persons receiving a prompt and proper bail hearing on Sunday and not simply being routinely held in a jail until Monday.

The Introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms

NOTE: This essay was written by Justice Shaun Nakatsuru

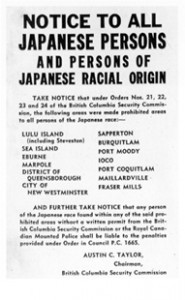

On February 24, 1942, an order-in-council passed under the Defence of Canada Regulations of the War Measures Act gave the federal government the power to intern all “persons of Japanese racial origin.” One consequence of this law was that men of Japanese origin between the ages of 14 and 45 were taken into custody and consigned to work as road camp labourers in the British Columbia interior or on farms in the Prairies.

The forced relocation and internment of persons who looked different from the mainstream of Canadian society – universally recognized today as a shameful injustice perpetrated on Japanese-Canadians – was the legitimate product of the democratic process. Parliament did what it was fully entitled to do under the prevailing constitutional law. Had a legal challenge to such an exercise of power been made to the courts at the time the order was issued, that challenge would not have succeeded. Parliament was supreme in its own domain.

Furthermore, such a challenge would have not been met with much sympathy by the white men (and they were almost uniformly white men) who were judges sitting in the courts. This was not because the judges were lacking in integrity or compassion. Rather, they were the product of their times. Judges were educated, practised as lawyers, and then presided when appointed, in the legal era when the Canadian constitution meant little more than the “peace, order, and good government” clause when it came to the concept of civil liberties.

In short, judges had a mindset that promoted the idea that the surest path to a civil, peaceful, and harmonious community was the strict application of law, the due promotion of social order, and the consequent preservation of the status quo.

Enactment of the Charter

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms has fundamentally changed this. Since its enactment in 1982, the Charter has imposed limits on the extent to which the state can interfere with the rights and freedoms of Canadians. In the criminal law context, the Charter is not meant to promote or protect collective rights or advance equality. It is primarily a means to delineate the boundary between an individual’s autonomy, his or her right to be left alone, and state action. In so doing, the Charter has changed the face of criminal justice in this country. No longer are individuals powerless to challenge state laws and actions that are supported by the majority. No longer are judges required to respect the choices of the executive or legislature when those choices violate fundamental societal values.

On Parliament Hill in Ottawa, on April 17, 1982, the Queen signed the Constitution Act, 1982 into law.

For the overwhelming majority of those interacting with the criminal justice system in this province, the Ontario Court of Justice is the face of justice in Ontario. The Charter has helped transform this Court. It has altered the face of justice significantly, and for the better. The following outlines some of the ways the Charter has had that impact.

Enhanced Powers and Responsibilities of the Court

First of all, the Charter has meaningfully enhanced the powers and responsibilities of the Court. This can be illustrated by a few examples.

Section 52(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 states:

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of Canada and any law that is inconsistent with the provisions of the Constitution is, to the extent of the inconsistency, of no force or effect.

The Charter, as part of the Constitution, is therefore given primacy over other laws. Early on in constitutional litigation, the question arose: could provincial courts such as the Ontario Court of Justice exercise this power under section 52(1)? The Supreme Court of Canada held that provincial courts have the power to declare legislation invalid in criminal cases and this included the power to dismiss charges where the legislation is invalid by reason of a violation of the Charter.[1] This declaratory power under section 52(1) was not the preserve of the superior courts. In effect, if an order-in-council such as that used to intern and relocate Japanese-Canadians during World War II resulted in charges being brought in the Ontario Court of Justice, and that order-in-council was found to be constitutionally invalid, then the Court’s decision would trump Parliament’s will. The charges, no matter how serious, would be dismissed. One can hardly imagine a greater authority or responsibility being given to a single, unelected, presiding judge.

In a similar vein, before the advent of the Charter, under the common law, judges had little discretion to exclude evidence based upon conduct of the investigative authorities. In other words, regardless of the nature and scope of illegal or unconscionable actions of the police, the judge was required to receive at trial any evidence uncovered as a result of those actions. But under section 24(2) of the Charter, a court is authorized to exclude evidence obtained in violation of Charter rights when its admission could bring the administration of justice into disrepute. The test for such exclusion has evolved, but its latest formulation requires a balanced approach be adopted whereby the factors taken into account give consideration to the seriousness of the violation, the effect on Charter-protected interests, and society’s interest in the adjudication of the charge on its merits.[2]

Right to Counsel and Freedom from Unreasonable Search and Seizure

When one considers some of the substantive legal rights defined under the Charter, clearly it has impacted not only the administration of justice, but also had a deep influence in the nature of policing in the community and the rights enjoyed by all. The right to counsel and the freedom from unreasonable search and seizure are two such legal rights. With respect to the former, individuals arrested or detained are in a vulnerable state under the control and direction of the police. The right to counsel recognizes the interest of such individuals to have ready access to legal advice; in particular to be advised of their right to remain silent and how to exercise that right. While there are always exceptions, the police generally recognize and respect the right to counsel of those who are under their authority. Many of the important right-to-counsel issues were litigated before the Ontario Court of Justice in drinking and driving cases.

With respect to the section 8 right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure, the care and attention the police pay to the limits of their authority and to the drafting of informations to obtain search warrants before intruding into the privacy of the subjects under investigation has significantly increased in the past years. While other explanations may have contributed to this change – including improved police force education and professionalism, for example – the threat of exclusion of important evidence if the Charter right is found to have been breached has played no small role as a catalyst. Being the over-seer of the vast majority of criminal cases – and situated so “close to the ground” when it comes to supervision of the police and familiarity with issues in the communities it serves – the Ontario Court of Justice has proved to be fertile ground for the nurturing of such substantive rights.

One specific case that could be cited relative to the section 8 right involved police use of sniffer dogs to uncover illegal drugs. [3] In that case, the Ontario Court of Justice judge found that searches at a high school by a sniffer dog and police were unconstitutional and excluded the evidence found as a result of such searches.

Landmark Case: Sniffer Dogs, School Searches, and the Charter: R. v. A.M.

In 2002, the police accepted a standing invitation from a principal at a Sarnia, Ontario high school to bring sniffer dogs into the school to search for drugs. The sniffer dog reacted to A.M.’s backpack and, without obtaining a warrant, the police opened the backpack and found illegal drugs. A.M. was arrested and charged with possession of drugs for the purpose of trafficking. A.M. argued that his right to be free from unreasonable search or seizure under section 8 of the Charter had been violated, and that the evidence should therefore be excluded under section 24(2) of the Charter.

The Ontario Court of Justice judge found that there were two searches conducted. The first was by the sniffer dog, which alerted the police to the presence of drugs. The second was the physical searching of A.M.’s backpack by the police officer. The judge found that both of these searches were “unreasonable,” and therefore unconstitutional and excluded the evidence. The Crown appealed this ruling to the Court of Appeal. That court agreed with the earlier ruling. Crown then appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Supreme Court of Canada held that students are entitled to privacy in a school environment and police do not have the right to conduct searches of public spaces when the search is not authorized by statute or at common law. Since there was no authority for the police search of A.M.’s backpack, it amounted to a violation of section 8 of the Charter. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the evidence should be excluded pursuant to section 24(2) of the Charter.

(R. v. A.M., [2008] 1 S.C.R. 569.)

Right to Trial Within a Reasonable Period of Time

Perhaps most controversial has been the section 11(b) guarantee according an accused the right to trial within a reasonable period of time. The implementation of this important right has not been an easy one and has not yet achieved much success in some instances. The dockets of the Ontario Court of Justice remain crowded and in some jurisdictions, particularly in large urban areas which have seen significant population growth, the time to trial has actually increased unacceptably. Early in the developing jurisprudence under the Charter, thousands of cases were stayed due to unreasonable delay in the Ontario Court of Justice. This led to much public criticism and a quick retreat by the Supreme Court of Canada in its approach to the test applied for determining whether this section has been violated.[4] That said, the right to a trial within a reasonable time has resulted in innovation in courts in Canada, including the Ontario Court of Justice: more reliance on diversion and alternative methods of dealing with charges; more effective pre-trial screening and disclosure; and a more active role for judges in managing cases and ensuring efficient and timely disposition, whether it be by guilty plea, preliminary inquiry, or trial. The traditional image of the passive and non-interventionist jurist engaged only when the accused is brought before the Court bears little resemblance to the reality of the role of the judge today. The requirements of section 11(b) have played a major part in development of this type of judicial activism.

Proceedings in criminal and penal matters

11. Any person charged with an offence has the right…

(b) to be tried within a reasonable time;

The Impact of the Charter on Judicial Independence

A second positive impact the Charter has had on the Ontario Court of Justice relates to judicial independence. Section 11(d) guarantees an accused the right to trial by an independent and impartial tribunal. The Supreme Court of Canada held that under this section, the Ontario Court of Justice enjoys constitutional independence from the government; thus, its judges are accorded security of tenure and financial security.[5] In other words, judges of statutory jurisdiction are treated in these fundamental provisions similarly to Superior Court judges of inherent jurisdiction. It is fair to say that provincial governments have increasingly come to appreciate the constitutional recognition of this status when it comes to working conditions and remuneration of Provincial Court judges. In turn, this has played a substantial role in attracting many more highly qualified applicants to the Ontario Court of Justice, thereby enhancing professionalism on the bench.

A Balancing Act: Charter Values and Court Decisions

The final way the Charter has significantly affected the Court is less tangible and more abstract, but at the same time, very apparent and real. It is not only the written text of the Constitution that informs the work of a judge; Charter values such as the fundamental freedoms, equality, respect for individual autonomy, and sensitivity to diversity and difference guide a judge’s hand when it comes to the interpretation of the common law and the exercise of discretion.[6]Charter values are also not confined within the workings of the criminal justice system. They pervade society. These values are informed by and in turn shape community and personal value systems. Charter values have greatly influenced the development of the Ontario Court of Justice. It is not a Magistrates’ Court of years past but a Charter Court: Charter values are protected, promoted, and promulgated in everything the Court does. This is not to say that such values are limitless, or that collective values such as community security or legitimate state interests such as law enforcement are ignored or sacrificed at the altar of individual freedom. It has always been, and remains, a Court of balance.

A good illustration of this balance – and how Charter values can infuse a decision even when not specifically raised – is provided by a case originating as a child protection matter in the Ontario Court of Justice.[7] Under section 7 of the Charter, the liberty interest of a parent was held to encompass the right to nurture and care for one’s child, including fundamental decisions such as those involving medical procedures. On the facts of that case, the parents, due to their sincere religious beliefs, refused blood transfusions for their infant child as a part of her medical treatment. The parents’ decision could have potentially threatened the life of the child. While the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that section 7 protects the right of the parent to make such a decision, this liberty right does not mean unconstrained freedom. In any organized society, individual freedom is subject to numerous constraints for the common good. While the state’s intervention in this case deprived the parents of their liberty interest, it was held this action was taken in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice in order to protect the life and well-being of the child.

Life, liberty and security of person

7. Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice

The Ontario Court of Justice decision in 1995 to grant the Children’s Aid Society temporary wardship so that the infant could obtain the blood transfusion was upheld. Beyond the important constitutional principles involved, this case is also noteworthy because the judge at first instance in the Ontario Court of Justice made the ruling without resort to the Charter. The case had been brought on an urgent basis and constitutional arguments were not specifically raised. However, the judge recognized the fundamental issue was balancing the rights of the parents with the right of the child and thus, even without expressing it, gave due consideration to competing values underpinning important rights and freedoms specified under the Charter.

Engaging the Basic Values of the Canadian Criminal Justice System