Brian W. Lennox: The Collaborative Leader

Annmarie E. Bonkalo: Leading the People’s Court

George Thomson and the Court

Stories

Brian W. Lennox: The Collaborative Leader

Introduction

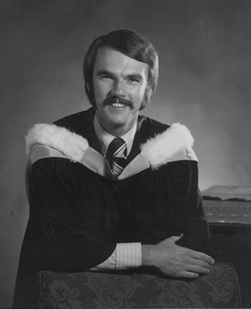

Brian Lennox discovered an interest in criminal law when his legal education began at the University of Toronto in 1968. “I liked the intellectual discipline of it, the elements of logic and reason. Plus, it had the ‘people’ aspect that some other areas of the law don’t,” he recalled.[1] He wondered if he might be a criminal lawyer one day.

That interest transformed into a passion in 1970 during the October Crisis. Lennox was serving as an intern working for Members of Parliament in Ottawa. He watched the House of Commons debates unfold around the War Measures Act. “The experience of working in Parliament changed my life and those debates over the War Measures Act confirmed my interest in criminal law.” During the October Crisis more than 450 people were arrested and held without charge. Lennox saw this as an abuse of power. It reinforced for him the necessity of a fair and just criminal process which respected the rights of all. That principled approach did lead Lennox into the practice of criminal law. By 1999 he had been appointed to the position of Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice – the busiest and largest court in Canada, hearing approximately 98 per cent of criminal cases in the province.

Early Years

“When I was young, I had no clue what I wanted to do with my life,” Lennox remembers. “I still really have no firm idea why I went to law school…. though my parents said that I always loved to argue.”

Born in Thornhill in 1946, Lennox moved with his family to Rothesay, New Brunswick when he was in grade 8. He began to learn French at school during that year in New Brunswick, but returned to the Toronto area for high school. His older brother, John, headed to Glendon College – then the only campus of Toronto’s York University. Lennox followed along in his brother’s footsteps. “John and I commuted from home together. Glendon offered a general first year program, which appealed to me; it was a new university, small and had a beautiful campus.” After first year, he studied political science and economics, and played varsity basketball for York (after a fashion): “I got my basic training for the Court through basketball…. I sat on the bench.” At Glendon, he also met his future wife, Susan Paton. They married in 1969.

Law School Days

Law school followed. It was a heady time at University of Toronto during those days. His professors included a future Supreme Court of Canada judge, Frank Iacobucci, and academics who greatly influenced the development of the law and the courts, including Alan Mewett and Martin Friedland. But Lennox’s true transformative moment came in 1970 when he saw a notice pinned to a bulletin board at U of T, advertising the Canadian Association of Political Science parliamentary internship program at the House of Commons.

Instead of his third year of law school, Lennox went to Ottawa and began working for Ken Robinson, a Liberal MP from Toronto. “I chose to work with him because, at that time, he was a member of the Justice Committee of the House.” Then there was the October Crisis, which was a riveting experience.

During the October Crisis, Lennox was working as a parliamentary intern in Ottawa. Lennox described those tense days in an interview for the Richmond Hill Post in April 2006: “Lennox was schooled not only by parliament, but also by the political upheaval of 1970s Ottawa. The FLQ crisis was in full swing and Lennox saw the War Measures Act put into motion, and the ensuing tension in the streets. He remembers an encounter with a soldier guarding the National Defence Headquarters. The infantryman pointed his rifle at a woman attempting to take his photograph. ‘I was stupid enough to say, “What are you going to do, shoot her?”‘ he says.” (Source: The Ottawa Journal, October 14, 1970.)

But “everything was set in motion for me when I began working for André Fortin.” A Quebec MP, Fortin was then a member of the Ralliement créditiste, which became the Social Credit Party. As part of his duties, Lennox began writing speeches for Fortin – in French. “At that time, my French wasn’t particularly strong and I learned a lot from being immersed in French in the office and writing those speeches.”

Paris Beckons

After returning to Toronto for his final year of law school, Lennox headed to the University of Paris on a French government scholarship for graduate studies in criminal law. The first of his three children, Britt, was born there. The scholarship did little to support a family of three. His father sent him a Globe and Mail article describing how difficult it was to land articling positions in Ontario. From Paris, Lennox began trying to locate an articling position in Ottawa, where the young family had decided to settle. He sent letters to every general practice law firm in Ottawa and received only two replies and one offer of a position. Unbeknownst to Lennox at the time, that offer was another transformative moment.

Practising in Ottawa

The law firm of Paris, Mercier, Sirois, Paris and Bélanger hired Brian Lennox by mail and the family returned to Canada in the autumn of 1973. Paul Bélanger, the lawyer who took a chance on the mail-order articling student and then kept him on after his articles, became Lennox’s long-term mentor and friend.

In the spring of 1974, Lennox returned to Paris to sit his oral exams and graduated with a Diplôme d’études supérieures de sciences criminelles. But his first years in practice were spent at the low end of the legal pile. “I was a beginning generalist in an excellent firm. I was horrible at real estate law and I didn’t like corporate law. I enjoyed litigation but wanted to do more criminal work.”

When he saw an opening for a part-time Crown Attorney in Ottawa, Lennox received the approval of the firm to apply for it. During the course of that competition, an opening for a full-time bilingual Crown became available when Assistant Crown Attorney Jack Nadelle was appointed to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). Lennox then applied for and received the full-time position.

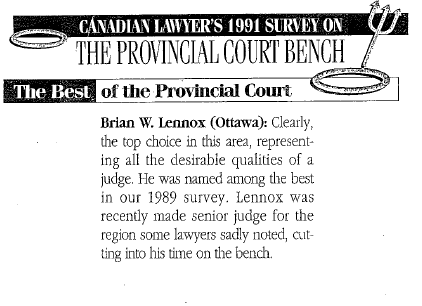

Prosecuting Criminal Cases

From 1978 to 1986, Brian served as an Assistant Crown Attorney, prosecuting criminal cases. “Roy McMurtry was the Attorney General in those days and I liked his approach to the Crowns. We were his ‘local’ ministers of justice. He took a very hands-off approach and gave independence and autonomy to us to do what appeared to be ‘right’ in individual cases.” But he wasn’t only working as a Crown. Lennox also began teaching various law courses – first at Algonquin College and then at the University of Ottawa. He taught a variety of subjects – from real estate to advocacy to criminal law.

In 1978, Paul Bélanger had been appointed to the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and sometime later he began encouraging Lennox to apply.

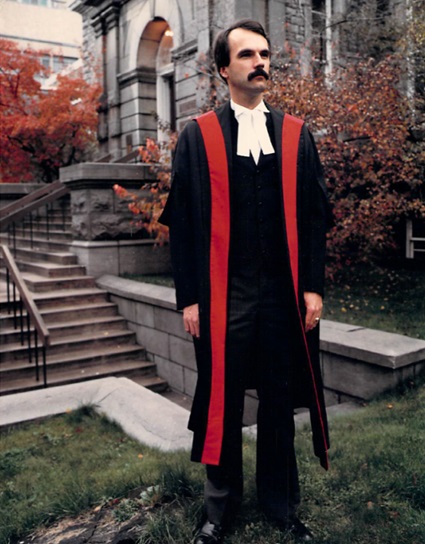

The Provincial Court (Criminal Division): A Natural Fit

The Provincial Court (Criminal Division) was a natural home for Lennox. “The Provincial Court did my kind of work – criminal matters – and dealt with real people with real problems. During the 1980s, more and more counsel were electing to have matters tried in Provincial Court because the Court was building its expertise in criminal law and changes in legislation were giving the provincial courts in Canada increased jurisdiction in Criminal Code matters.”

“The application process for a judicial appointment in those days was very simple. I only needed two letters of recommendation. I had no connections so I just put in my application and waited. The process was pretty summary, although I wouldn’t be surprised if Paul Bélanger had a hand in it. I was called down to Toronto in August 1986 to meet with the Judicial Council, where I was interviewed by Chief Judge Hayes of the Criminal Division, Chief Judge Andrews of the Family Division, Chief Justice William Howland (Chief Justice of Ontario), a couple of other judges and some others, including an Anglican minister. I was told shortly after that I would be appointed, but that I could not tell anyone until it was officially announced.… On September 25, 1986, I was driving home from work, listening to the CBC news and heard the announcement that a new judge had been appointed in Ottawa – and that it was me!”

Life as a Provincial Court Judge

Chief Judge Fred Hayes’s practice was to bring newly appointed judges to Toronto for about three weeks of training by observation. As Lennox recalled, the program was fairly rudimentary, sitting in court and watching more experienced judges make decisions. Within the first couple of years following appointment, Hayes asked Lennox to chair the Court’s University Criminal Law Program. At that time, all other education for criminal law judges was controlled by the Association of Provincial Criminal Court Judges of Ontario. The University Program was the only one over which the Chief Judge had full control.

This education work had two unexpected but crucial outcomes for Lennox and his long-term judicial career: it brought him into closer contact with the Chief’s office and solidified his reputation as an educator within the Court. It also allowed him, over time, to meet every criminal law judge on the Court.

In his early years on the bench, Lennox felt in many ways that he had been appointed to the “Ottawa Court” as opposed to the “Provincial Court.” There was little interaction with judges and justices of the peace from other parts of the province. “The Provincial Court in those days was decentralized – we all worked in our own silos.”

The Possibility of a Single, Unified Trial Court?

By the end of the 1980s, everyone on the Court knew of the court reforms proposed by Attorney General Ian Scott, including the ultimate merger of all existing trial courts into a single, unified institution.“The big change arrived on September 1, 1990 with the first phase of court reform. The High Court and District Courts merged to become the Ontario Court (General Division). The Criminal and Family Divisions of the Provincial Courts were joined to become the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) with only one Chief Judge – the newly appointed Sidney B. Linden.[2]

It looked as though the planned reforms would fall apart when, on September 6, 1990, the governing Liberal party lost the election and Ian Scott moved into opposition. “There was all kinds of speculation and worry in the Court after that. Sid was an unknown. He’d never been a judge before. It was an uncertain time. And it was made more uncertain when it became apparent that the proposed second phase of court reform, the merger of the General Division with the Provincial Division would be delayed indefinitely.”

Lennox was already beginning to see the plan that Linden had in mind to guide the new Provincial Division forward – and he was impressed. Knowing of the merger to come in September 1990,[3] Linden set about putting an administrative structure in place to cope with the coming changes, including the appointment of a group of Regional Senior Judges (RSJ), one in each of the eight regions of the province.

Once again, Paul Bélanger influenced Lennox’s career. Bélanger, the logical candidate for the RSJ position in the East Region, encouraged Lennox to consider the position should he, Bélanger, not be appointed. When Lennox demurred, pointing out that he had no administrative experience or particular interest in the position, he recalled Bélanger asking him: “It could be anybody, why not you?” Linden had met Lennox and, from Lennox’s work on the Court’s University Program, sized him up as intellectual, strategic and academic, in addition to being a solid judge. He also knew that, unlike many of the more senior judges on the Court who were concerned by Linden’s lack of experience as a judge, Lennox was willing to support his plans for administrative changes to the Court.[4]

Lennox received the RSJ appointment in July 1990 – and quickly set to learning about court administration, while maintaining his involvement with the Court’s educational programming.

The new collection of Regional Senior Judges and Senior Advisors, in November 1990. Back row, left to right: G. Michel, G. Campbell, J. Evans, B. Lennox, D. August, G. Lapkin (Senior Advisor, Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace). Front row, left to right: B. Walmsley (Senior Advisor, ACJ Family), M. Hogan, S. Linden (Chief Judge), H. Momotiuk. Missing: R. Walneck. (Courtesy: S. Linden.)

Working in Judicial Administration

As RSJ, Lennox was tasked with bringing together the judges of the former Criminal and Family Divisions of the Court in the East Region. This proved to be relatively easy in Ottawa, where the criminal and family law judges had been working together in the same space since the opening of the Ottawa courthouse in 1986, but somewhat more difficult in the larger region. The integration of the former Provincial Courts and their judges was made more complicated by the proposed expansion of the Unified Family Court (UFC) from Hamilton to other parts of the province, an initiative that was supported by the new provincial government: many family law judges in the Provincial Division were anxious to maintain their position as clearly specialized family law judges in the event that the UFC did expand,[5] and the majority of criminal law judges were not particularly interested in doing family law cases.

A Variety of New Court Structures

The new court structures – and the Chief Judge’s Executive Committee (CJEC) created by Sid Linden in particular – made the 1990 transition a joint responsibility. Linden ensured that all of the RSJs were given training and experience as well as specific responsibilities and devoted the majority of the time at frequent CJEC meetings to administrative matters.

Within six weeks of the creation of what Lennox has often referred to as “the modern Ontario Court of Justice”, the Supreme Court of Canada, in its October 1980 Askov decision, changed the nature of judicial administration within the province. No longer was it good enough to do business-as-usual: management by the Court of its cases, resources and court lists became of critical importance and the Court shifted into crisis mode. The response, in large part due to the collective leadership taken by CJEC and to the workload assumed by all of the judges of the Court, was generally successful. Innovative case management and scheduling practices, together with different forms of case triage minimized the impact of the Askov decision. In Ottawa,[6] Lennox was responsible for a series of criminal law practice directions that regularized pre-trial conferencing and promoted early resolution where appropriate. Similar practices were adopted in the area of family law. Another lasting feature of the Askov crisis was a closer working relationship among the justice “stakeholders”, including the Court, courts administration, the crowns, police and the Bar.

Roberts and Lennox: Two New ACJs

In autumn 1995, Lennox (October) and Marietta Roberts (September) were appointed respectively to fill the two newly created positions of Associate Chief Judge and Associate Chief Judge-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace within the Ontario Court (Provincial Division). In the early 1990s, Chief Judge Linden had begun relying on Lennox’s skill in the realm of judicial education: “Any time an education program needed to be beefed up, I’d lean on Brian,” Linden recalled.[7] That made Lennox a natural choice for his ACJ position. In that role, he chaired the Education Secretariat, responsible for the design, development and delivery of education to the judges.

Leading Education Secretariat

The creation of the Education Secretariat was but one of the many administrative innovations introduced during the early 1990s – radically changing court operation on an institutional level. Prior to its introduction, judicial education had been principally run by the two associations of judges – family and criminal. Education seminars had been the only way judges could get together for purposes of association meetings and business: “For this reason, in the early years, education was but one of many purposes served by holding education seminars. Later, the educational component of the seminars became much more important.”

“Sid created the Education Secretariat – with equal numbers of judges appointed by the Chief Judge and the two associations – and providing a significant autonomous budget as well as giving it a supervisory and coordinating role over programming. This meant there was now a formal body, representing all judges, responsible for education. The creation of the Education Secretariat was a recognition of the need for and importance of continuing education for all judges.”

At first, the judges’ associations appeared to be somewhat wary of the Secretariat, but they soon came to see its value in providing quality education and they appreciated the shared decision-making authority and responsibility. At the same time, Chief Judge Linden recognized the legitimate need of the judge’s associations to meet both as an executive and with their judge members and provided specific funding and an opportunity for those meetings.

A Steep Learning Curve

In his new administrative roles, Lennox was learning how to handle the unanticipated challenges, including surprise announcements from the government. “I was apoplectic!” recalled Lennox of the December 1995 meeting when he and Roberts were advised by the Assistant Deputy Minister (in the absence of the Chief Judge, who was on holiday) that the government was making budget cuts in the order of 30 per cent across the whole of government, including the Court.

“Given the fact that over 90 per cent of the budget of the Court went to pay judicial salaries and benefits, the proposed level of cuts was impossible and the proposal itself created a real potential for significant harm to the justice system. Sid agreed that something had to be done to create a record of our concerns and so he and I sat down and starting drafting a letter.”

Before the letter was sent on January 17, 1996, Linden showed it to both Charles Dubin, Chief Justice of Ontario, and Roy McMurtry, Chief Justice of the General Division of the Ontario Court of Justice. They agreed to sign the letter together with Linden. It was an unprecedented move – a court rebuking an Attorney General for proposing budget cuts without a full and proper consultation.

“We would urge you to seek a moratorium on any cuts to the administration of justice until a proper analysis of the impact of any proposed cuts can be made,” read the letter to the Attorney General Charles Harnick. “They could severely limit public access to justice and could put at risk some of the most vulnerable members of our society,” the letter continued. That letter became front page news on January 31, 1996, following its leak to the press. “Cuts mean justice chaos top judges warn,” read the headline in the Toronto Star.[8] According to the Globe and Mail, this vocal criticism of the government by members of the judiciary was a “highly unusual foray.”[9]

As a result of the judges speaking out, Harnick pulled back on the proposed budget cuts for the justice system. Lennox learned from this experience that moments of crisis can have unexpected – and positive – outcomes. “The collective action of the three Chiefs, heralded a time of cooperation amongst the three Courts that had not previously existed and has since continued,” he observed.

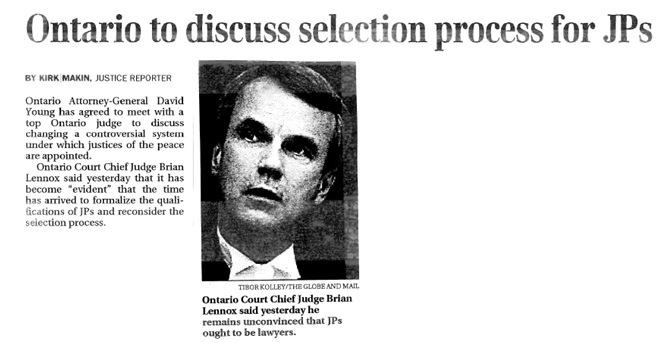

During Lennox’s tenure as ACJ, the Ontario Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee was formally recognized in legislation. JAAC – as it became known – vets applicants to the Court, and produces a short, ranked list of candidates from which the government must choose appointees. JAAC was created as a pilot project in 1989, but not statutorily recognized until 1994.[10] Since its inception, JAAC “has been recognized as a model of independent, rigorous and objective judicial appointment process.” As many commentators have pointed out, the efforts of JAAC have resulted in a “very strong bench, untainted by patronage.”[11]

A Witness to a Profound Evolution

From the time of his call to the Bar in 1975, Lennox had been a witness to and later a participant in the evolution of the Provincial Courts. On different occasions, he has listed a number of factors in this evolution.

- The elimination of the grand jury, and of summary conviction appeal by trial de novo, the existence of both of which diminished the value of the work of the judges of the Court.

- The formal requirement in the 1980s of 10 years’ experience as a lawyer as a condition of appointment.

- The rise of the judges’ associations and their subsequent merger.

- The increasing recognition of the family and criminal law expertise of the Court.

- The development by the judges’ associations of the framework agreement to settle issues of remuneration.

- The creation in 1989 of the Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee process, ensuring the highest quality of judicial appointments, a process that has become an aspirational model for other jurisdictions.

- The merger of the Family and Criminal Divisions of the Provincial Courts in 1990 under the strong administrative leadership of Sidney Linden.

- Continuing high quality judicial education, since 1995 under the auspices of the Education Secretariat and later with the National Judicial Institute.

- The creation in 1995 of the modern Ontario Judicial Council.

- Continuously expanding jurisdiction in criminal matters by legislative enactment and as a result of accused elections for trial in Provincial Court.

A number of these factors have been largely mirrored for the justices of the peace in the areas of administrative structure, associations, appointment, discipline, remuneration, and education.

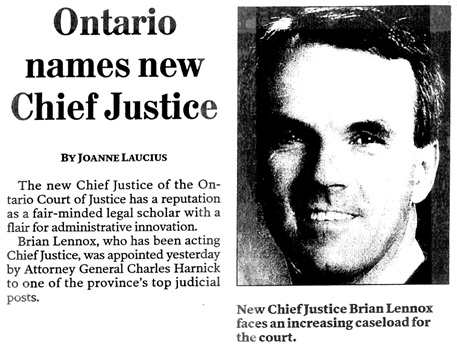

By the time he became Chief Justice in 1999, Lennox could see the progress the Court had made over time: “The administrative structure of the Court fashioned by Chief Justice Sidney Linden in the 1990s, the rapid expansion of its jurisdiction and the outstanding quality of the judges of the Court and of their work has led to the creation of a modern and progressive Ontario Court of Justice…” “From my vantage point as ACJ and Chair of the Education Secretariat, I could see a Court that was growing in reputation and capability because of the consistently high quality of new appointments, but its judges were still suffering from many decades of being considered the ‘lowest’ rung on the judicial ladder in the province. I knew that the Magistrates’ and early Provincial Courts were no longer: that the Ontario Court of Justice was a modern, progressive, expert Court and that its judges could grace any Court in Canada. But, as Sid Linden had said on more than one occasion in speaking of our judges, ‘They had been down so long, they didn’t know up.’ It was time for everyone to appreciate the true nature of the Court.”

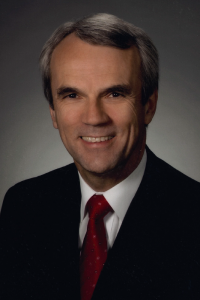

Chief Justice Brian W. Lennox

Chief Justice Brian W. Lennox (left) at his swearing-in as Chief Justice, Ontario Court of Justice, on September 19, 1999. At right is Justice David Wake who was sworn in as Associate Chief Justice that day. Associate Chief Justice of Ontario, Coulter Osborne, stands between Wake and Lennox. (Courtesy: Lennox Family.)

On April 19, 1999, the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) became the Ontario Court of Justice.[12] Chief Judge Linden became Chief Justice Linden – until Chief Justice Lennox was appointed on May 3, 1999. Lennox started with a number of advantages that Linden did not have when he was first appointed: Lennox had been a sitting judge before becoming RSJ and then ACJ: he had come to know and be known by virtually every judge on the Court, largely through his involvement with judicial education. There was also a sense that the era of significant and sometimes worrying changes had come to an end. The Court itself was stronger than it had been in 1990: its appointment process, its judges and its administrative structure had attracted the attention of a number of other courts. By May of 1999, the newly created Ontario Court of Justice had earned a particular place in the Canadian judicial system.

Making His Priorities Clear

When Lennox was sworn in as Chief Justice, much was made of his contributions to judicial education. In his remarks at the swearing-in ceremony, Attorney General James Flaherty called that commitment “the hallmark of his career.” Lennox duly announced that increasing judicial education would be one of his top priorities.[13] The first step would be solidification of the relationship with the National Judicial Institute (NJI) and the provision of formal support for the Court’s educational programs by the NJI. “I saw myself as a consolidator of the gains we’d made during Chief Justice Linden’s tenure – and one of the key ways of doing that was through the delivery of excellent continuing education.”

Lennox thought that Ontario had a more important role to play in judicial education: as the largest Court in Canada and one of the best resourced, he wanted to ensure that the benefits of the Ontario Court of Justice/NJI partnership be available to all judges. To that end, in the Memorandum of Understanding negotiated by Associate Chief Justice David Wake with NJI Executive Director George Thomson, the Court agreed to partially fund an NJI position dedicated both to the Court and to Provincial Court education. As part of that agreement, all education developed by or for the Ontario Court of Justice was to be freely available to any court and to all judges. The agreement led to a new approach to education within the Court and to innovative programming that was later presented to a much broader, national audience. It also led to the formal training of a large group of judicial educators, among them a number who have gone on to national and international education programs: judges such as Katherine McLeod, Miriam Bloomenfeld and Joseph Bovard, to name but three.

Maintaining and Building Relationships

As Chief Justice, Lennox maintained and built upon the relationships that Sid Linden had fostered. Meetings of the Chiefs of the three Ontario Courts were a regular occurrence (Lennox has often said that his meetings with the legendary Chief Justices Patrick LeSage and Roy McMurtry early in his mandate were highlights of his career). He continued or instituted regular contacts with the Law Society of Upper Canada, the Ontario Bar Association, the Advocates’ Society and the Criminal Lawyers Association, among others, and became a regular at Bar events and receptions.

Within the Court, Lennox met frequently with the judges’ associations and their presidents, maintaining the tradition of association consultation and participation in CJEC. Regular, periodic meetings were scheduled with the Attorney General and Deputy Attorney General, and with Assistant Deputies Attorney General as required. While fully protective of its independence, the Court recognized that current Canadian constitutional structure required co-management of the courts, in which the Court saw itself as the leading partner.

In his administrative role, Lennox was greatly assisted by what he calls “an unbroken succession of outstanding public servants” in the position of Executive Coordinator of the Court. That position, created by Chief Justice Linden, had the effect of freeing the chief judge from routine matters of administration to concentrate on the most essential parts of the operations of the Court.

Lennox maintained the collaborative style of leadership within the Court that had been established by Linden. CJEC and its various committees were the focus of decision-making and he relied heavily on the Regional Senior Judges for the administration of the Court within each region. The RSJs in turn were seconded by Local Administrative Judges at various court locations. His closest collaborators were the Court’s Associate Chief Justices: Marietta Roberts and then Don Ebbs as ACJ-Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace and David Wake and Annemarie Bonkalo as ACJ. Each of the ACJs had important provincial responsibilities and all worked closely together. Lennox credits much of his and the Court’s success to his colleagues in the Office of the Chief Justice. It was important for the Court that the Office of the Chief Justice to be open, collegial and mutually respectful and that the Court speak with one voice, both internally and externally.

Facing Challenges and Changes

Consolidator was not the only role Lennox filled. He faced both challenges and changes during his tenure as Chief.

One of the people who watched Lennox grow into his new position was David Wake, who replaced Lennox in the ACJ role he vacated when he was appointed Chief Justice. “There’s a certain naiveté to Brian,” stated Wake. “He doesn’t see the bad side of human nature as easily or clearly as others. But once things become apparent to him, he deals with things. He has a tremendous backbone when he needs it.”[14]

Within months of his appointment, Lennox needed that backbone when dealing with challenges to the JAAC appointment process. Lennox maintained an arm’s-length relationship with JAAC: he had and retained an implicit trust in the judgment of the Committee. The quality of its process and of its appointments was such that, unlike some other jurisdictions, the Chief Judge did not have to get involved in the appointment process. Lennox was, however aware of apparent discontent within government over the independent appointment process.

That discontent became public when the media reported that the government had refused to make an appointment to the North Bay court after the Premier had allegedly promised the appointment to a particular candidate – a candidate who had not been on JAAC’s recommended list and was therefore ineligible for appointment. The delay in appointment to North Bay extended for well over a year, affecting the Court’s ability to provide an appropriate level of service. Neither the government nor JAAC was prepared to yield and there was at least one reportedly heated meeting between JAAC and the Attorney General. It was then rumoured that the government was preparing legislation to amend the appointment process. In the end, no legislation was forthcoming and JAAC continued as it had in the past.

Additional Points of Friction

In April, 2000, a government backbencher introduced a private member’s Bill in the Ontario legislature, Bill 66, the Judicial Accountability Act, 2000, which would have required the Attorney General to table an annual report identifying individual judges and the sentences they imposed in serious criminal cases. The proponent of the Bill indicated that one of its purposes was to “…motivate lenient judges to give out tougher sentences.”[15]

An Attempt to Motivate “Lenient” Judges to Give Out Tougher Sentences

In May 2000, a private members’ bill, which called for the publication of judges’ sentencing records, was introduced by Marilyn Mushinski, a Progressive Conservative member of the Legislative Assembly. Mushinski made the following comments when introducing the bill:

Mrs Marilyn Mushinksi (Scarborough Centre): This bill will require the Attorney General to table an annual report of the sentences that are handed out by judges in serious, non-plea bargained criminal cases compared to the maximum sentence under the law. This will let the government, law enforcement agencies and the public at large know which judges believe that stiff sentencing is an important way to protect law-abiding citizens and motivate lenient judges to give out tougher sentences.

The bill was condemned by the Criminal Lawyers’ Association. Alan Gold, then president of the association called it “a blatant attack on the independence of the judiciary.”

The bill was never passed into law.

(Sources: Excerpt from Ontario Hansard, April 18, 2000, upon first reading of the Judicial Accountability Act, 2000. April Lindgren, “Soft judges’ score cards under fire: Lawyers condemn bid to pressure judiciary to give higher sentences,” Ottawa Citizen, May 16, 2000, p. A6.)

The Bill provoked an immediate negative reaction from the Law Society of Upper Canada, the Canadian Bar Association and others, but received initial support from the Attorney General, with which it went to Second Reading and was referred to Committee. Although the Bill died in Committee, the surprising fact that it passed Second Reading was indicative of the sometimes difficult relationship that existed at that time between the government and the Court and one that made occasionally for awkward meetings between the Chief Justice and the Attorney General.

The Justice of the Peace Appointment Process

Some of those meetings dealt with justices of the peace. In the early 1990s, the NDP government had put in place an informal justice of the peace appointment process. The Ministry placed newspaper advertisements asking for applications for appointment as a justice of the peace. The process was administered by the Regional Director of Courts Administration in each region and involved local selection committees which included a lawyer and judge. In the absence of any formal criteria for appointment, some of the advertisements elicited hundreds of applications. The local committees reviewed the applications, selected a small number of candidates for interview, interviewed and made recommendations for appointment to the Attorney General.

The informal process quickly fell into disuse and by the mid-1990s, the only vehicle for the appointment of justices of the peace was the Justice of the Peace Review Council (JPRC). The JPRC’s role was limited to interviewing candidates that were sent to it by the office of the Attorney General and advising whether they were suitable for appointment or not. On occasion, candidates with absolutely no knowledge of the work of a justice of the peace presented themselves before the JPRC on the recommendation of their local member of the Legislative Assembly. The situation was untenable for everyone involved and both the Court and the Attorney General were looking for a more satisfactory process.

At one meeting, Lennox agreed with the Attorney General that absolutely no further appointments would be requested or made until the Court came up with a systematic rationale for each request for appointment. Early the following week the Minister’s office sent an unsolicited list of more than a dozen candidates to be interviewed by the JPRC. Lennox correctly surmised that the Minister would soon be changing portfolios.

Successive Coordinators of Justice of the Peace from Gerald Lapkin to ACJs Marietta Roberts and Don Ebbs had been urging the Attorneys General with whom they dealt to create a meaningful appointment process for justices of the peace. They met with little success until the early 2000s when the Ministry of the Attorney General agreed to change the process. In 2007, following consultations led for the Court by ACJ Ebbs, the Justices of the Peace Act was amended to create the Justices of the Peace Appointments Advisory Committee (JPAAC). The Act further stipulated qualifications for appointment, criteria for selection and an application, review and interview process that did much to modernize the justice of the peace bench and that was much more consistent with the important role of the justices of the peace within the Court.

Justices of the Peace and “POA Devolution”

Justices of the peace were also involved in another significant government initiative during Lennox’ tenure as Chief Justice: “POA Devolution,” or the transfer of prosecution and administration responsibilities for provincial offences courts from the provincial government to the municipalities. What this meant in practical terms was that provincial offences would no longer be dealt with in provincial courthouses but in a variety of municipal premises across the province. The government also agreed to transfer most of the provincial offences revenues to the municipalities.

Decided without consultation with the Court, this change meant that, for municipalities, the fines imposed by justices of the peace became part of the municipal revenue stream. The municipalities, by agreement, paid the Ministry an hourly fee for justice of the peace services and some sought to maximize their return on investment. Initially, the tensions created led to concerns that certain municipalities were not fully aware of the principle of judicial independence.

One ongoing institutional challenge facing Lennox during his time as Chief Justice related to the family law jurisdiction of the Court. It had always been assumed that there was broader support for the creation and expansion of Unified Family Courts than for any other type of court unification. In the first phase of Ian Scott’s court reform, while he had unified all civil jurisdiction within the General Division, he had deliberately left family court unification and the creation of a unified criminal court until the second phase. Scott feared that there would be no support for the creation of a unified criminal court if family court unification was completed first. Accordingly, the second phase of court reform was to see the simultaneous creation of a Unified Family Court and a Unified Criminal Court within a single level trial court.

Unified Family Court Expansion Stalls

Although the prospect of the second phase of court reform disappeared with the Liberal government’s defeat in the 1990 election, there continued to be significant support for the expansion of the Unified Family Court in Ontario. A first expansion occurred in 1995, a second in 1999. Subsequently, the federal government introduced legislation creating funding for a number of UFC judicial posts that could have in theory allowed the completion of UFC expansion throughout all of Ontario. Nothing came of that legislation and UFC expansion in Ontario has been stalled since 1999.

Family law judges within the Ontario Court of Justice were originally brought into the merged Court in 1990, at a time when it appeared that many of them might shortly be appointed to an expanded UFC. With considerable justification, they felt largely ignored during the Askov era, when the energies of the Court were necessarily focused on resolving criminal backlogs. Fewer in number than the criminal law judges of the Court, some family law judges regretted the fact that they were no longer a separate and independent court and were worried about being submerged in a predominantly criminal law court. This is the background against which every Chief Justice of the Court has worked since 1990.

As Chief Justice, Lennox always took the position that UFC expansion in Ontario should be completed as quickly as possible. Together with most of the family law bench and bar, he saw the UFC model as providing the best service to families in Ontario, with a cadre of dedicated family law specialist judges working within a specialist court. “I really have great difficulty understanding why UFC expansion has stalled. It either works well, as I believe it does, or it does not. If it works well, it should be quickly extended throughout the province. If it does not, it should be fixed, or, if it cannot be fixed, abandoned and replaced. Families in difficulty deserve access to the best justice system that we can devise.”

While many of the Court’s family law judges have been disappointed by the lack of progress on UFC expansion, they have not only persevered, they have thrived within the Court. The JAAC appointment process has continued to provide a steady stream of talented and committed family law specialist judges whose expertise is widely recognized. “You would be very hard put to identify a group of more creative, innovative and energetic judges than the family law judges of the Ontario Court of Justice. They are passionate about their work and dedicated to assisting children and families in crisis. I was always proud to be Chief Justice of a Court that had such exceptional judges in it,” stated Lennox.

At the swearing-in of Annemarie Bonkalo as Associate Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice on October 6, 2005, a collection of the “builders” of the Court gathered. Left to right: Former Chief Justice Sidney Linden, Chief Justice Roy McMurty (Chief Justice of Ontario and former Attorney General), Associate Chief Justice Annemarie Bonkalo, Attorney General Michael Bryant, Chief Justice Brian Lennox, former Attorney General Ian Scott. (Photo: Ashley and Crippen, Courtesy: S. Linden.)

The Result of JAAC

The theme of the exceptionality of the judges of the Court is a common one for Lennox. “The outstanding reputation that the Ontario Court of Justice has enjoyed may well be due in part to its leadership, but its true success comes from the judges. By this, I mean of course the judges who have been appointed through JAAC, but also each and every one of their predecessors. Many of them had been magistrates or became judges at a time when there was no prestige associated with the office of provincial judge. Salaries were low, the court room was often a parish or a legion hall, offices and staff were sparse or non-existent and the judges were frequently treated as civil servants. Independence was little more than a text-book notion.”

“Yet it was those judges, working in isolation, who over the years, day by day, case by case, developed the knowledge and expertise, the ability to deal with real people in real time and who made the court what it is today: a proud and independent institution, dedicated to justice and to public service, peopled with judges who could easily grace any courtroom in the country. That is what makes and has made the Ontario Court of Justice.”

Move to the National Judicial Institute

Lennox’s career came full circle in 2007 when his eight-year term as Chief Justice concluded. He returned to Ottawa and his long-term passion: judicial education.

Since his days as Regional Senior Judge he had been involved with the work of the National Judicial Institute – as a consumer of the educational services and resources they offered. In addition, he had served on the NJI Board of Directors from 1999 to 2005. Now, he was heading to the NJI to become its Executive Director.

As he had assumed each new position, Lennox had specific goals and objectives in place. Resources allowing the NJI to provide services to provincial courts across Canada had been limited since the NJI was first created. The NJI Board of Governors, chaired by Chief Justice of Canada Beverley McLachlin, had always been supportive of NJI involvement in the education of provincially-appointed judges and viewed its mandate broadly, encompassing both federally and provincially-appointed judges. The manner in which the NJI was funded, however, meant that most of its funding was derived from presenting programs to federally-appointed judges.

“A key part of my role was to find ways to allow provincial courts and provincial judges to participate fully in the NJI’s education initiatives and to encourage them to do so.” he stated. “We were able to do that in a variety of innovative ways, including encouraging provincial court judges to participate in the online courses that the NJI offers and providing them with access to the collection of legal e-resources and course materials created specifically for judges. The NJI also provided training programs in adult learning techniques for Provincial Court education chairs, and NJI’s educators and staff were always available as education resources.” Lennox also continued the tradition of the NJI Executive Director meeting regularly with the Provincial Courts’ Canadian Council of Chief Judges.

Lennox was particularly proud of the fact that, as he had envisaged as Chief Justice, the MOU between the Ontario Court of Justice and the National Judicial Institute became a true partnership and the Court became a national leader in judicial education. Each of the partners benefited from the experience and expertise of the other: the Court and the NJI worked closely to develop programming, program ideas and techniques that found their way into NJI initiatives that were presented to larger judicial audiences, both of provincial and of superior court judges.

Largely because of the administrative and financial control that the Court had over its resources (under its MOU with the Attorney General), the Ontario Court of Justice has been able over the years to leverage its expertise in judicial education to benefit not only the NJI but also judges and courts across Canada.

Suite et fin

Lennox left his position as Executive Director of the National Judicial Institute in July of 2014. He retired from full-time service with the Court in October of that same year. He has remained involved in judicial education projects and in 2015 became a judge in residence at the Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa.

In 1986, a generous – and prescient – article about Brian Lennox and his appointment to the Court appeared in the Ottawa Citizen: “Lennox is known among colleagues, adversaries in the defence bar, and court staff as an honourable, intelligent man. ‘He is gracious in defeat and doesn’t gloat in victory,’ says lawyer Robert Meagher. ‘His integrity is above reproach.’”[16] Interviews with many of his colleagues on the Ontario Court of Justice for the history project demonstrated that those qualities exemplified his tenure on the Court and beyond.

- All quotes from Brian Lennox come from a collection of interviews for OCJ History Project, 2013-15. ↩

- Hayes had been appointed to the District Court and Linden, appointed in April 1990, had replaced him as Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) in the early summer of that year.↩

- Though the changes to the Court arrived on September 1, 1990, Linden had actually been sworn in as both Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division) and Chief Judge of the Ontario Court (Provincial Division) on June 27, 1990 – replacing Fred Hayes as Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Criminal Division). ↩

- Interview of S. Linden for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- UFC expanded in 1995 and again in 1999. ↩

- The Askov decision had little impact in the East Region outside of Ottawa. ↩

- Interview of S. Linden for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Tracey Tyler, “Cuts mean justice chaos top judges warn,” Toronto Star, January 31, 1996, p. A1.↩

- Kirk Makin, “McMurtry attacks cuts in judiciary,” Globe and Mail, February 2, 1996.↩

- Courts of Justice Statute Law Amendment Act, 1994, S.O. 1994, c. 12. The Act was proclaimed on February 28, 1995.↩

- Professor Wayne MacKay, quoted in Kirk Makin, “Ontario system eliminated patronage in choosing judges, proponent says,” Globe and Mail, April 27, 2012.↩

- Courts Improvement Act, 1996.↩

- Joanne Laucius, “Ontario names new Chief Justice,” Ottawa Citizen, April 27, 1999.↩

- Interview of D. Wake for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Hansard, April 18, 2000.↩

- Abby Deveney, “Prosecutor appointed to bench,” Ottawa Citizen, September 25, 1986.↩

Annmarie E. Bonkalo: Leading the People’s Court

Annemarie “Amie” Bonkalo had big shoes to fill. Her two predecessors – Chief Justices Sidney Linden and Brian Lennox – were legendary. Linden had achieved administrative independence for the Court, while Lennox personified and promoted the highest standards of judicial excellence. Everyone was watching to see how the first woman serving as Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice would make her mark.

Bonkalo truly appreciated the transformational work that preceded her. As Chief Justice, she wanted to ensure the Court continued to benefit from these hard-won achievements. But she did much more than that, in ways that may not have been fully appreciated because of her understated manner.

Bonkalo saw her role as forging a collaborative and non-hierarchical approach to leadership. Her goal was to modernize the Court in ways that would help people coming before it and not just serve the convenience of judicial officers and administrators. “We are the people’s court,” she said. “The Ontario Court of Justice is the face of justice for the people of Ontario.” Her legacy includes an unwavering commitment to education and support for justices of the peace, the judicial officers most commonly seen by members of the public.

Quietly and without fanfare, she made her mark.

Making a Life in Canada: The Perry Mason Years

Amie Bonkalo was born in Stockholm, Sweden to parents who had grown up in Budapest, Hungary. The family immigrated to Canada in 1949 when Amie was 9 months old. The Bonkalo family adjusted well to life in Toronto, but the city was not then the diverse place it later became. It was tough to have a foreign-sounding name. A more mundane challenge, Amie recalled, was not being able to find a bakery that sold what her parents considered to be a decent loaf of bread.[1]

Bonkalo’s father was a neurologist and psychiatrist, as well as a professor at the University of Toronto. Bonkalo remembers her father engaging his two daughters in debates at the dinner table, often playing the devil’s advocate and challenging them to think about the other side of an argument. This proved to be an excellent foundation for the legal career that Amie Bonkalo ultimately pursued.

Her mother’s options as a new immigrant were limited; her efforts were devoted to raising her two daughters – and she was determined that both would have the opportunity to attend university and become professionals. At age ten, Bonkalo found her first professional role model: television defence attorney Perry Mason. Her mother soon discovered that the most effective form of discipline was not letting Amie her watch her favourite show.

From Criminology to the Law

After completing high school at Branksome Hall in Toronto, Bonkalo majored in sociology and political science at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. There she developed an interest in criminology which she later studied in a new Master’s program at the University of Toronto.

In 1973, Queen’s Law School in Kingston reserved 25 first-year admissions for women. This encouraged Bonkalo to apply. After being accepted, she received advice from Mary Alice (“MA”) Murray, well known as the sole woman in the first graduating class from Queen’s Law. Murray went on to serve as the school’s Law Faculty Secretary and Registrar. Knowing the attitudes toward women in the legal profession, Murray advised Bonkalo that in order to succeed in the world of law, women had to be “better than the men.”

Bonkalo was not comfortable with law school at first. “I felt they were twisting our thoughts about what was right and wrong and forcing us to think in a narrow way. This went against my father’s pedagogical approach of always looking at both sides of an argument.” As time went on, Bonkalo realized the law was her calling. She credits professor Stanley Sadinsky’s lectures in civil procedure as inspiring her to want to practise law: “He made litigation real.” Criminal and constitutional professor John Whyte similarly nurtured her desire to pursue criminal law. Bonkalo also developed an interest in family law, although she articled at a Toronto firm specializing in real estate and civil litigation.

In her early years of practice, she continued to be hampered by a last name that was still regarded as unusual in Toronto: “Pronouncing it was problematic for some in the profession. When I mention that these days, people are surprised because Ontario has now become such a diverse society.”

First Female Assistant Crown in Peel

After being called to the Bar in 1978, Bonkalo obtained an interview for a Crown prosecutor position in Peel Region. Her application stood out because of her Master’s degree in criminology. She tried to hide her surprise when the all-male interview panel handed her a warm beer – which she drank – and asked if she was planning to get married and have children. The interview eventually moved on to more substantive issues and she became the first female full-time Assistant Crown Attorney in Peel.

In 1979, Amie married Gerald Sadvari, a lawyer she had met while at Queen’s. By the time she gave birth to the second of their three children, a full-time workload – including County Court jury trials – made it difficult to spend enough time with her family. Bonkalo arranged to work part-time and only in the Provincial Court. She credits her mentor, Crown Attorney Leo McGuigan, for agreeing to what in those days was an unusual arrangement.

Amie and Gerald received child care help from “a nanny and a granny”. The granny was Bonkalo’s mother, who resided with them after her husband passed away.

From Prosecutor to Judge

After 12 years as an assistant Crown Attorney, Bonkalo applied for one of two judicial vacancies in the Brampton Provincial Court. She thought her chances were ruined when Attorney General Ian Scott witnessed her husband performing a “rather naughty and satirical song” about wanting to be a judge at a bar association function. These fears were unfounded. On April 2, 1990, Annemarie Bonkalo and Justice Rebecca Shamai were appointed as the first female Provincial Court judges in Peel Region.

Bonkalo was age 41 at the time of her judicial appointment. She remembers Ian Scott commenting: “That is awfully young – I hope you don’t get bored.” She did not get bored. Amie Bonkalo went on to become a Local Administrative Judge in 2000, a Regional Senior Judge in 2004, an Associate Chief Justice in 2005, and achieved the Chief Justice position in 2007.

Shortly after being appointed to the bench, Bonkalo consulted old court transcripts to find precedents as to how judges had spoken to parties about the trial process, sentencing, bail and other matters relating to criminal proceedings. She transcribed these details in a notebook and began using it as a guide when sitting in court. Before long, copies of that handwritten “benchbook” became a hot commodity among her judicial colleagues. She shared it willingly with all who inquired – a first experience in providing support to her peers. Bonkalo took great satisfaction in helping others to succeed.

Breaking into Judicial Administration

During an assignment at Finch Court in North York, Bonkalo became interested in judicial administration. This accelerated when she and Justice Maryka Omatsu were assigned to the College Park Court in downtown Toronto. At first the two women took care not to intrude on the “old boys club” atmosphere of the room where the other judges – all male and much older – met for lunch.They felt that the men’s attitudes toward women on the bench would change once they got to know their new female colleagues. After a few months, the women became well accepted. Local Administrative Judge Charles Scullion became a mentor for Bonkalo and recommended her to take on his position when he retired.

Justice Omatsu remembered these days well. “When Amie and I moved from North York to College Park, the judges were much older than us and they were all white men. They phoned the regional senior judge, Bernie Kelly, and said, ‘We don’t want those two women to come here.’ Bernie said, ‘Do you think this is a democracy? They are coming!’ But when we got there the men were civil and quite nice. Amie made it clear to Scullion – the local administrative judge – that she wanted to be the new LAJ. There was a bit of resistance, but she won them over and became the new LAJ. There wasn’t any hostility when that happened. At College Park, everyone came into Amie’s office, including the cleaning staff. She was sympathetic and a problem solver.[2]

A New Model of Judicial Leadership

Sometimes, outside 1 Queen, people didn’t see the leadership that was quietly and firmly given by Amie. When I was the Associate Chief, I was highly visible and engaged in a lot of projects. She was keen to give credit and profile to others, never self-aggrandizing. She was very humble, which is a commanding leadership style. She trusted the people working with her and let them do what their strengths allowed. But at the end of the day, she made the decisions.

Former Associate Chief Justice Peter Griffiths[3]

In 2005, Bonkalo became an Associate Chief Justice, working closely with Chief Justice Brian Lennox and Associate Chief Justice Donald Ebbs at 1 Queen Street East in downtown Toronto. That was her first glimpse of the role of the Office of the Chief Justice. “The average judge, to this day, has no idea about what happens at 1 Queen. They don’t understand that we don’t just cut ribbons.”

Promoted to Chief Justice in 2007, Amie Bonkalo became first woman to serve in this role. Many of her colleagues assumed the position would go to a male candidate. According to Omatsu, “Amie is warm and nurturing. I like that but it is not a male leadership style which is what many people expect.”[4]

Bonkalo was undeterred by the sceptics. She stayed true to her belief in collaborative leadership and shared decision making, especially for significant determinations that affected the Court. She was also a delegator: “If I give people a job and I trust them to do it well, they will rise to the occasion.” She followed the model established by her predecessors to meet with the Regional Senior Judges as a group and enable them to lead their regions without interference. “I come to swearing-in ceremonies in the regions across Ontario as a guest, not to run the show. The Regional Senior Judges are in charge of these events.”

Court – I simply make different

types of decisions from other

members of the judiciary.”Annemarie Bonkalo

She kept in mind that the other members of the Court were her peers and she made great efforts to be respectful, fair and supportive. “I am not the boss of any court – I simply make different types of decisions from other members of the judiciary.”

Many people have spoken about Bonkalo’s kindness on a personal level. Former Associate Chief Justice John Payne shared the following anecdote. “I am allergic to garlic. My wife and I had arranged a cruise to Spain, Italy, Turkey, France and Greece. The Chief was so concerned about my allergy that she arranged to have cards typed – in each language of the countries we were attending – to explain my allergy. This kind and thoughtful gesture is something that I will never forget.”[5]

Payne also observed that Bonkalo “worked tirelessly on behalf of the Court and the people of Ontario. At 1 Queen Street during her tenure, everyone worked together closely and supported each other. It was like a family. Her exemplary leadership skills were recognized when she was chosen as the Chair of the Canadian Council of Chief Judges. She became the ‘leader of the leaders’ of the Provincial and Territorial Courts across Canada.”[6]

Justices of the Peace: The Face of Justice

A hallmark of Amie Bonkalo’s tenure as Chief Justice was treating justices of the peace with respect and supporting them as true judicial officers. She and her associate chief judges understood well that justices of the peace were the “face of justice” for large numbers of people.

|

TREATING JUSTICES OF THE PEACE AS JUDICIAL OFFICERS

|

| (Source: Former Associate Chief Justice John Payne) |

A Transparent Court: Connecting with the Community

An accessible and accountable people’s court was central to Bonkalo’s approach as Chief Justice. Part of being a people’s court is helping the public to understand what the Court does and how it operates. An example recalled by Peter Griffiths was the quick adoption of new criminal rules: “Overnight we went from dozens of arcane rules (modelled on those of the Superior Court and widely ignored) to only five rules written in plain language. In an era of increasing numbers of self-represented litigants, people need tools that will open the door of justice rather than obscure it.”

“It is very important for people

to see us as approachable and

human.”

Annemarie Bonkalo

Under Bonkalo’s leadership, the Court developed guides – expressed in plain language – for self-represented litigants in family, criminal, and POA proceedings. She also encouraged judges and justices of the peace to speak with media students, community organizations, and college law classes. She asserted, “It is very important for people to see us as approachable and human.”

The Court also led the way in Canada for making statistics about court hearings available to the public by posting quarterly family, criminal and provincial offences court data on the website. A policy was introduced to make it easier for the media to obtain digital recordings of court proceedings, and a protocol implemented to permit electronic recording devices in the courtroom unless there is a contrary court order in a particular case.

Technology: An Incremental Approach

Technology is an important part of modernizing the Court. Bonkalo’s approach was to make incremental improvements, one step at a time –as opposed to large scale technology projects that tended to collapse under their own weight. In 2013, the Court initiated e-orders, a simple innovation that eliminated hours of waiting for documents. By installing a printer in the courtroom, the clerk can type the order, produce a hard copy, and hand it to the party concerned without delay. “We have to make it possible for people to minimize their time in court. People have jobs they need to get to,” the Chief Justice noted. While the Courts lag behind many other sectors in terms of technology, such effective, incremental steps have made a difference.

The Family Bench

Because Bonkalo came from a criminal law background, she endeavoured to ensure that the family judges, who represent a much smaller bench than their criminal counterparts, felt well served by her office and received sufficient attention and visibility for their issues. In 2014, she created the position of Senior Family Advisory Judge, filled by Justice Deborah Paulseth, to chair the family advisory committee, sit on the rules committee, and advance issues of the family court bench.

Mentorship

Amie Bonkalo never forgot the help she got in earlier years from mentors such as Crown Attorney Leo McGuigan and Local Administrative Judge Charles Scullion. As a judicial leader she became a strong proponent of mentorship for judges and justices of the peace. She felt that peer mentoring could provide orientation and practical ideas for managing the workload and time pressures. Mentorship could also help stimulate people to continue learning and take on new challenges in later years to avoid burnout. Her commitment culminated in strengthening the mentorship program for newly appointed justices of the peace.

Chief Justice Bonkalo pictured with – from left to right – Associate Chief Justice/Co-ordinator of Justices of the Peace, Faith Finnestad; former Chief Justice of Ontario, Warren K. Winkler; Chief Justice Bonkalo; and Associate Chief Justice Lise Maisonneuve, ACJ Maisonneuve became Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice in May 2015. (Courtesy: A. Bonkalo)

Diversity – Changing Face of the Court

Chief Judge Bonkalo was delighted with the role advisory committees play in the selection of justices of the peace and judges for the Ontario Court of Justice. “They were able to get the best person for the job and also to increase the diversity of both benches.” To Bonkalo, diversity on the bench meant that judges and justices of the peace learn from each other and become more understanding of the diverse public they serve.

In her early days on the bench, Bonkalo witnessed first-hand how diversity could change the way judges approach their work. She noticed her male colleagues modify their outlook as more women were appointed – “from rethinking sexual stereotypes to being less likely to use sports analogies.”

Throughout her career, she was conscious of breaking through barriers affecting women in the legal system: “I always felt that, as a woman, I had to proceed with my career cautiously. It was as if I had a glass floor underneath me and I had to do things carefully, sensitively and thoughtfully. I didn’t want to break it for fear that it would harm the future for other women.”

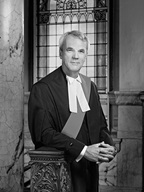

Raising the Profile: Pictures in the Gallery

Walk the halls of Osgoode Hall and you will see dozens of portraits, including many stern looking gentlemen in formal dress from the 1800 and 1900s. They are chief justices of various courts in Ontario and Treasurers of the Law Society of Upper Canada. This collection serves as a valuable visual record of the history of the top levels of the judicial and legal professions in Ontario. Until January 2014, however, there was no recognition of the existence of the Ontario Court of Justice – the provincially appointed part of the court system.

The Law Society recognized the Ontario Court of Justice for what it had become –the largest court in Canada filling an essential role in the justice system. On January 29, 2014, portraits were unveiled of the three Chiefs who served the Court since its creation in 1990 when the Criminal and Family divisions of the former Provincial Court were merged. The portraits of Sidney Linden, Brian Lennox, and Annemarie Bonkalo now hang on the walls of Osgoode Hall as tangible symbols that this Court matters.

Looking Back to Look Forward

As the end of Amie Bonkalo’s tenure as Chief Justice was approaching, she began reflecting on what the Court had accomplished and challenges that remained to be addressed by her successor.

She realized that further improvements in the evolution of the Court were necessary. In Family Court, her main concern was with child protection cases, an area that would benefit from more intensive judicial education and improved interactions with Children’s Aid workers and the Office of the Children’s Lawyer. She was also concerned that the structure of the Court had not transformed sufficiently to meet the growing complexity of criminal cases. “Our Court was set up to give oral judgments and to handle one or two trials per day along with pre-trials and set dates. An impaired driving case used to take two to three hours; now it takes two to three days.” This has led to a much stronger commitment to pre-trial resolution and case management, but further progress needs to be achieved.

Court has evolved can help to

inform discussions of where it

should be heading in the future.”Annemarie Bonkalo

In reflecting back, Bonkalo also realized that the history of the Ontario Court of Justice was not well known. She believed that “an understanding of how the Court has evolved can help to inform discussions of where it should be heading in the future.” After discussions with the Associate Chief Justices and other judicial leaders, Bonkalo launched a project to produce a history of the Ontario Court of Justice. In keeping with her desire for the Court to be modern and accessible, she asked for the history to be an engaging, online resource instead of a traditional “coffee table” memorial book. She specified that the history should focus on transformative events, profiles of participants and stories illuminating significant changes.

Annemarie Bonkalo made history when she became the first female Chief Justice for the provincially appointed bench. Part of her legacy has also been to ensure that the rich history of the Court will be preserved for generations to come.

- Information and quotations in this profile about the Chief Justice’s childhood, education and early career come from interviews of A. Bonkalo for OCJ History Project, 2014. ↩

- Interview of M. Omatsu for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of P. Griffiths for OCJ History Project, 2015. ↩

- Interview of M. Omatsu for OCJ History Project, 2015.↩

- Interview of J. Payne for OCH History Project, 2015. ↩

- Interview of J. Payne for OCJ History Project, 2015. ↩

George Thomson and the Court

A few years ago, I called George Thomson with a request: “Would you be interested in writing a history of the Ontario Court of Justice?” The Court’s history was not well known and I wanted someone to document stories about its many changes, challenges and achievements. I thought of George because of his long association with the Court in different capacities:

George said he would do it subject to one condition. He wanted two writers to co-author the history with him: Karen Cohl and Susan Lightstone. I happily agreed and the OCJ eHistory project was launched. The eHistory contains many stories and profiles. This is George’s story, written by his co-authors and included at my request. |

The Lure of Family Law

George Thomson originally intended to become a labour lawyer. He articled at a Toronto labour law firm and subsequently headed off to complete a Master of Laws at the University of California, Berkeley in the turbulent late 1960s. Upon his arrival at Berkeley, George was dismayed to learn that their labour law professor was on sabbatical. His disappointment did not last long. Herma Hill Kay, who later became the Dean of Berkeley Law, was teaching family law using an influential book by Foote, Levy and Sander[1]. The text did not just explain the law – it also discussed what was actually happening in families and where the law was succeeding or failing to serve them. “I fell in love with family law there,” said Thomson. “That was when I first realized the importance of the Family Court, which had been invisible in my law school education.”[2]

George Thomson originally intended to become a labour lawyer. He articled at a Toronto labour law firm and subsequently headed off to complete a Master of Laws at the University of California, Berkeley in the turbulent late 1960s. Upon his arrival at Berkeley, George was dismayed to learn that their labour law professor was on sabbatical. His disappointment did not last long. Herma Hill Kay, who later became the Dean of Berkeley Law, was teaching family law using an influential book by Foote, Levy and Sander[1]. The text did not just explain the law – it also discussed what was actually happening in families and where the law was succeeding or failing to serve them. “I fell in love with family law there,” said Thomson. “That was when I first realized the importance of the Family Court, which had been invisible in my law school education.”[2]

While at Berkeley he began to come around to the view that family courts are often required to solve problems which fundamentally are not legal but social.

From a profile of George Thomson by June Callwood, The Globe and Mail, 1976[3]

Teaching about Children and the Law

Thomson became a law professor in 1968 at the University of Western Ontario[4] where he taught family law among other subjects. At the time, a typical family law course covered marriage and divorce. It did not focus on the child and the proceedings that came before the Family Court. He wanted to broaden the approach as his mentors in Berkeley had done and as John Barber, a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School, had begun to do in Ontario.

Thomson devoted the first month of his course to an examination of the concept of ‘illegitimacy’ and the impact that label had on parents and children. “As part of the course, I got a friend to take on the role of a pregnant single parent who was seeking legal and practical answers from her lawyer. This freaked the students out. They were terrified at the prospect of a real client with both legal and non-legal challenges. At first they couldn’t see why they needed to know about issues such as access to welfare.”

At Western, Thomson developed a course on children and the law and did a lot of teaching and writing on juvenile delinquency. With no thought at the time of becoming a Provincial Court family judge, he was developing expertise in the specialized areas of law at issue there.

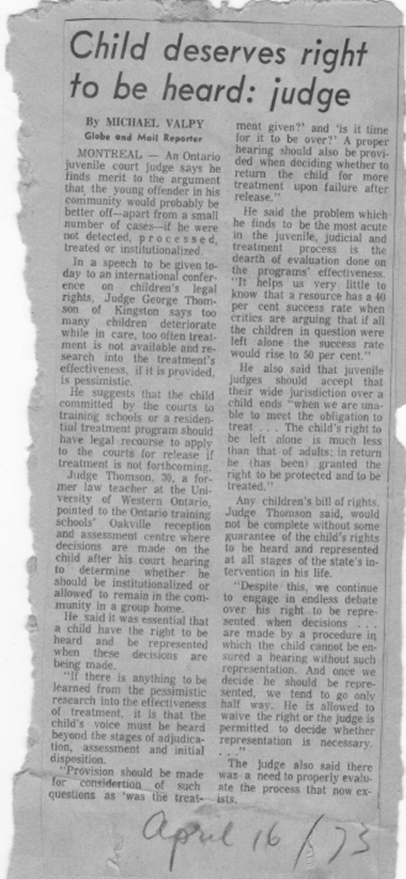

He became especially troubled by section 8 of the Training Schools Act. That provision allowed children to be sent to training schools for being unmanageable, even though no offence had been committed. “When judges sent kids to training school, the transcript from the court hearing went with them. I gathered many of the transcripts and was horrified. In some cases, the CAS would come in and basically say, ‘Sally is hard to manage,’ and the judge would send her to training school with virtually no due process.”

While still at Western, Thomson was invited by Chief Judge Ted Andrews to speak to judges of the Provincial Court (Family Division). Thomson reciprocated by involving judges in his courses. He created a partnership with the local Family Court judge in London, Maurice Genest, so law students could assist unrepresented children and families in the courtroom. Thomson’s connection to the Court was growing stronger.

Cutting Short a Trip Around the World

In 1972, after a few years of teaching, Thomson decided to travel for a year. While he was away, a vacancy arose in the Family Court in Kingston. Dalton Bales, then Ontario’s Attorney General, was seeking younger candidates to join the Family Court. Ted Andrews was in favour of appointing Thomson and several local people with political influence also recommended him. Andrews reached Thomson in Switzerland by phone.

George Thomson was over in the Alps skiing when the opening came up in Kingston…I checked him out, great… so I phoned him up… and he said, “I have just gone on my sabbatical, and I have still got six months to go,” and I said, “well, if you don’t do it now, George, you might not get the chance.”

Ted Andrews, former Chief Judge of the Provincial Court (Family Division)[5]

Thomson cut short his trip to become the Family Court judge in Kingston. He was 30 years old.

Early Days as a Judge

The court building in Kingston, then on Brock Street, did not live up to Thomson’s grand image of a place for the dispensing of justice. “It was a decrepit red brick residential house and hearings were held around a table in the dining room, while those waiting sat in the small living room.”

Thomson’s very first case came before him the morning after the day he was sworn in as a judge. “The boy in front of me was charged with murdering his brother in a fight over what television shows to watch. His father had guns all over the house. It was for me a baptism by fire.”

Like all new appointees, Thomson wondered how he was supposed to prepare for the job. “I was given some materials to read and then I was sent out to watch five judges at work. That was it for training at that time and it just made me more terrified about what I was taking on. I knew a lot about family law but was obviously weak on procedure and evidence issues. Horace Krever, a colleague at Western, was an acknowledged expert in evidence and so, for a while, if I had a significant evidence problem I would reserve and call Horace to get me started.”

Judge on a Motorcycle

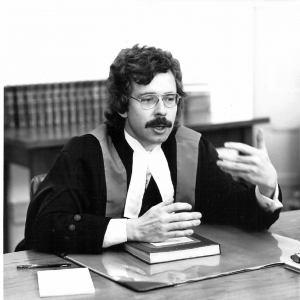

Thomson was aware that he did not fit the image of a traditional judge of the 1970s. In June Callwood’s profile of Thomson, she wrote, “A rumpled figure in turtleneck sweaters and corduroy pants, he looks more suited to his Triumph motorcycle than to his judge’s black robes.”[6] Thomson recounts an incident that occurred when he traded places with a judge in Toronto.

The first time I arrived at the courthouse at 311 Jarvis Street in Toronto and parked my 1965 Triumph 500 motorcycle, I was ordered to leave the judges’ parking area by a security guard. The Court was not yet used to younger judges like me and Rosie Abella.

A “Community Motivator”

As a family judge, Thomson quickly realized that he was limited in his ability to respond to children and families in crisis due to juvenile delinquency, acts of violence, or marriage breakdown. Desperately needed community resources and programs simply were not available to support the people he was seeing in his courtroom. With the encouragement of his Chief Judge, Thomson began working with the Kingston community to develop a Family Court Clinic to assess children and their families, an observation and detention home, a juvenile diversion program, a volunteer probation service, a shelter for abused women, a youth crisis centre and several new community-based group homes for youth. While one of the early judges to embrace the role of “community motivator,” he wasn’t alone. “Many family judges across the province responded willingly to Chief Judge Andrews’ expectation that they take on a leadership role within their communities. This was a distinguishing feature of the Provincial Court (Family Division) in the 1970s.”

Law Students

At Queen’s Law School in Kingston, where he first studied law, Thomson taught family law including a course on children and the law. He and Professor Heino Lilles[7] arranged for law students to come to the Court, appearing on cases to aid unrepresented parties or assist local lawyers. Before long, the involvement of law students had become an important resource at the Court.

One law student who evidently made a lasting impression on him was Judith Beaman. After she became a lawyer, they started dating and were married in 1977. That is not Beaman’s only connection with the Ontario Court of Justice. She was appointed as a judge in 1998 and later served as the Regional Senior Justice in the East Region.

Thomson well remembers a project involving Donna Hackett, a future Provincial Court judge, when she was a law student.